Recline of the West: Couches and Psychoanalysis

How did psychoanalysis get its couch?

By Benjamin Aldes WurgaftSeptember 21, 2017

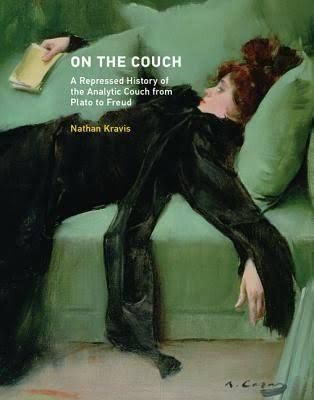

On the Couch by Nathan Kravis. MIT Press. 224 pages.

MY FATHER WAS 56 years old and I was 18, and we carried a new addition through the door of our small Victorian house in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The new addition was a psychoanalytic couch, itself a little Victorian-looking. It was upholstered in a rose-patterned fabric, its surface banking up at one end to form a cushion where the patient’s head would lie. My father had chosen it as the couch he would use during his training to become a psychoanalyst. (He had already been a practicing psychotherapist for years.) Unlike the thousands of couches manufactured by the Imperial Leather Furniture Company of Queens, New York, in the 1940s, whose designer boasted of having made the model used by Sigmund Freud himself (he was lying, and Freud had died in 1939), this couch had not been created for the purpose of psychoanalysis: it was just an ordinary piece of furniture, called to an extraordinary vocation by virtue of its surroundings. We placed the couch carefully against the wall of the office where my father saw patients. We set a comfortable office chair behind the head of the couch, so that the person lying down would not see the person sitting in the chair.

The analytic couch is a charismatic object, the most recognizable visual icon of psychoanalysis save for Freud’s own face. It remains iconic even as psychoanalysis has lost its foothold as a therapeutic practice, replaced by therapies less curious about, and less insistent upon, the depth and dignity of our internal lives. More than a century since the publication of Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams, only a fraction of a percent of the professional therapeutic work done throughout the world is formal psychoanalysis, which typically consists of multiple sessions per week, conducted with the patient or “analysand” recumbent on a couch. In On the Couch: A Repressed History of the Analytic Couch from Plato to Freud, Nathan Kravis, a practicing analyst and trainer of analysts, helps us understand the striking survival not only of the couch but also of the tradition it represents.

Readers of Kravis’s slender volume may be surprised to learn that the couch is not thickly theorized within the analytic literature. There are no cogent arguments on behalf of couches in Freudian or post-Freudian theory. Nor is there empirical evidence that the couch is critical to successful psychoanalytic treatment. Non-recumbent talking and listening have had their proponents. C. G. Jung abjured the couch and held face-to-face sessions; other analysts, including W. R. D. Fairbairn and Erich Fromm, have used chairs, oriented so that analyst and analysand simply look away from one another. In his 1913 essay “On Beginning the Treatment,” Freud stated that he asked his patients to lie down on his couch because he disliked being stared at all day long. As Kravis observes, “That’s not much of a theory of technique.”

Freud’s full description of his choice runs as follows:

I must say a word about a certain ceremonial that concerns the position in which the treatment is carried out. I hold to the plan of getting the patient to lie on a sofa while I sit behind him out of his sight. This arrangement has a historical basis; it is the remnant of the hypnotic method out of which psychoanalysis was evolved. But it deserves to be maintained for many reasons. The first is a personal motive, but one which others may share with me. I cannot put up with being stared at by other people for eight hours a day (or more). […] I insist on this procedure […] to isolate the transference and to allow it to come forward in due course sharply defined as a resistance.

Far from being a Freudian innovation, then, the couch is actually a vestige of older therapeutic approaches. Before developing the techniques of psychoanalysis, Freud himself practiced hypnosis, as well as a massage or “pressure technique,” and electroshock therapy, all of which utilized recumbent postures. The couch was a holdover from such practices, an atavism not unlike the persistence of extra pelvic fins on some dolphins, traces of terrestrial hind legs.

Freud’s couch, now on display at London’s Freud Museum, was a gift from a former patient. The famous “Smyrna rug” that he laid across it was a present from his father on the occasion of his engagement to Martha Bernays. The couch is not flat. A patient lying on it would have their upper body and head quite elevated, perhaps even at a 15-degree angle, yielding a posture I associate with hospital beds. When I look at images of Freud’s couch, I can’t help but think that lying on the Smyrna rug would feel uncomfortably hot.

Kravis’s book is more than a monograph on Freud’s couch, or on the thousands of analytic couches it inspired. He attempts to track the development of recumbent postures and recumbent speech in Western thought and culture from the ancient world to our modern one. This project is less idiosyncratic than it sounds; scholars have long taken posture, and the furniture that supports it, as an object of historical inquiry. As the architectural historian Siegfried Giedion put it, “Posture reflects the inner nature of a period.” In his 1948 book Mechanization Takes Command, uncited by Kravis, Giedion devoted considerable attention to chairs, benches, and couches, and to all manner of plain or upholstered variants upon them. “When the nomads plundered Rome,” he writes, “they found chairs that made no more sense to them than the statues, the thermae, the inlaid furniture, and all the instruments of a differentiated culture. Their habit was to squat on the ground, and so it remained.” The past is a foreign country; they sit down differently there.

Kravis, for his part, begins with the ancient world. Our word “recline,” he reminds us, comes from the Greek term kline, or couch. In ancient Greece, to recline at meals or at the wine-quaffing events called symposia was originally a marker of status, and eventually a practice shared by all social classes. The custom is thought to have originated in the Near East, and to have been emulated by the Greeks beginning roughly in the seventh century BCE. Kravis also points out the psychoanalytic foreshadowing within the Greek practice of “incubation”: sleeping in temples in hopes of receiving a divine visitation in a dream. But despite giving Plato pride of place in his subtitle, Kravis does not rest here long, quickly embarking on a hurried, almost flipbook-style tour through the history of recumbence: bas-reliefs of Assyrians feasting in a reclined position, Italian mosaics depicting a supine Last Supper.

While the term “couch” (from the French coucher, to lie down) was in use in English from the 13th century, the sofa in something approximating its modern form only appeared in Europe beginning in the late 17th century, its name taken from the Arabic soffah (a cushion). Kravis explores the role of sofas and couches in the history of intimate conversation in modern Europe, not to mention all the styles of portraiture, primarily of women, in which such furniture featured. It was on painted couches that painted women were depicted as readers, as thinkers, and as sexual objects or even, on occasion, subjects, in works such as François Boucher’s Madame de Pompadour (1756) and Pierre-Antoine Baudouin’s The Reader (1760).

The penultimate phase in the couch’s development was what Kravis terms the “medicalization of comfort,” the belief among doctors and patients that the ill or injured needed rest, relaxation, and leisure as part of the healing process. The use of recumbence in 19th-century rest cures is seen perhaps most famously in tuberculosis treatments, like the “luft-liegekur” or “air-rest cure” that involved lying back on specially built chairs, “cheap, portable, and easily sanitized,” in the open air. Such cures were part of the medical culture in which Freud himself received his training. At the same time, other specialized medical couches were being put into use, in particular for obstetrics and dentistry.

On the Couch promises to teach us something about the causal chain of developments through which the analyst and analysand got their couch. But rather than dive deep into a few especially relevant and proximate topics, such as the use of recumbence in hypnosis, Kravis wants to offer a grand historical arc of lying down and talking, to argue that there is something about lying down in ancient Athens that bears on lying down in modern Vienna. In Aristophanes’s The Clouds, Socrates says to Strepsiades, “Just lie down there […] and try to think out one of your own problems.” This is in fact the epigraph to Kravis’s book, and it is an excellent one, but to paraphrase Tertullian, what has Athens to do with Vienna? The reader needs this explained. Otherwise the relationship between different historical modes of recumbent speech, whether divided by geographic boundaries or by years, remains inferential or imagistic. It’s easy enough to look at old images and texts and spot familiar objects and postures; but how can we know in what terms such things were couched, at the time of their couching?

¤

To be supine in the presence of another person is to be vulnerable. It requires the kind of trust into which your spine relaxes. It demands something relatively soft — though not too soft. In her gorgeous series of images of psychoanalysts’ offices, the photographer Shellburne Thurber illustrates what analysts and patients have known for generations: the couch is where the analysand’s body meets an expression of the analyst’s personality, albeit a subtle one, a choice of furniture. One of Thurber’s photographs shows an analytic office in which the couch has a rail on one side. It happens that the rail is positioned along the office wall, but it is very tempting to see it as a kind of crib, its position easily reversed to keep an infant, or an infantile adult, from tumbling to the office floor. I would not be very comfortable with the persistence of that association, myself.

Since 2003 and ongoing as of this writing, I have been in psychoanalysis. My analyst’s couch is dark red in color and modern in its lines, and very comfortable. At the foot end there is a small rug to protect the upholstery from shoes, but it took me several weeks to fully understand the rug’s purpose and stop removing my shoes before lying down. A napkin protects the head of the couch from the patient’s hair. This couch was, and remains, located against the wall in an office in a Victorian house in a neighborhood of Berkeley, California, known as the Gourmet Ghetto, about three long blocks from the university campus where I used to be a graduate student. The house is perched up off the street, positioning it above a Thai restaurant in another building below, which I might have been able to see if I ever, in all the years I have lain down on that couch, got up to look out the window. There are curtains at the sides of the window, their two halves linked by an unobtrusive lace that forms a border above the window. For years I have noted that the curtains and the lace have not moved. Neither human hand nor gust of wind has changed their contours. There is a specific curl of white lace, above the window, whose exact position and shape have outlasted some of my friends’ marriages.

That curl has also survived several stretches of years when I have not lived in the Bay Area. At those times, my analyst and I have conducted my psychoanalysis over the phone. During these sessions I have had to imagine the contents of my analyst’s office from far afield. Equipped with a cellular telephone, I’ve been a free-range analysand. The list of physical circumstances from which I have phoned my psychoanalyst is long: reclining on a non-psychoanalytic couch in a furnished sublet in Brooklyn; lying on a bed in Paris, or on a grassy slope overlooking a lake in a public park in Los Angeles; suspended in a hammock (my personal favorite for comfort; I don’t know why analysts don’t use them) in northwestern Maine; sitting cross-legged on the floor of a motel room in western Massachusetts with the phone plugged into the wall because it was almost out of batteries and I had arrived to check in at the motel only a few minutes before the session. I once called him from the outskirts of a music festival in the Southern California desert. I have conducted more than a few sessions while walking down city streets or country lanes or while circling city parks. I have phoned my analyst while sitting in parked cars, the seat cranked back. When I’ve been back at my father’s home in Cambridge, my father has been kind enough to let me use his office and couch for my sessions. I do not know how many others in the history of psychoanalysis have conducted a phone session with their analyst from their own father’s analytic couch. Perhaps it is in the nature of psychoanalytic practice that such achievements remain hidden under the veil of confidentiality.

My father once suggested to me that the telephone might be the perfect medium for psychoanalysis, better even than the couch itself. There is nothing but voice and ear. All the problems of attention and direct vision that Freud resolved using the couch, are rendered moot by Alexander Graham Bell’s invention, which came on the scene just a few years before Freud’s couch. I am not sure my father is right, but his point puts pressure on the matter of the couch’s necessity. The psychoanalytic literature, as Kravis notes, offers no specific argument for, or defense of, the couch. There is only the test of practice and use and the weight of tradition, which is not nothing. There is much more to the couch, by this point, than the strategic avoidance of eye contact. Having been analyzed in many postures and in many places, I can report that lying down on my analyst’s couch feels best. The absence of distraction helps me. The familiar objects in the office are a signal, often unnoticed, that it is time to enter into free association, or at least to try. If Kravis is correct that recumbent speech in analysis represents “the affirmation in the presence of another of having a mind of one’s own,” then the phone certainly suffices, but sufficiency is not always enough.

Lying down on my analyst’s couch I first feel my body against the upholstered surface, and then, in a transition once novel and now familiar, my consciousness moves from my skin to the weight of my body. When I speak I can feel my voice in my throat and in my chest. In certain moods my eyes dart around the room, and fasten on a painting (a Chagallish cow frozen in mid-leap above the couch, next to the window), or a plant in its pot. But more often than not, even as my eyes half-focus on the track lights on their rails, my attention is internal. It is not that the rest of the world, or the rest of my life, vanishes for 50 minutes. Rather, by reclining I shift my perspective on that world and that life, and by reclining next to my analyst’s chair, observed but not observing, I literalize the idea that I may not be the foremost expert on my own experience. Time develops a different thickness, consecrated to a purpose, and I am reminded of the lovely short book, The Sabbath, in which Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel suggested that the Jewish people had built a cathedral out of time, rather than out of brick and mortar.

¤

After completing two out of three cases required of training analysts, my father decided not to finish his training and practice as an analyst. He continued, until very recently, to practice as a psychotherapist, his work informed by his analytic studies and training. The couch stayed put for about 20 years after its installation, even though I was often the only person to use it. Only last year, when my father retired, was it time to send the couch back into the world. In our part of Cambridge you can tell the turning of the academic year by the possessions that scatter on the brick sidewalks like red, yellow, and orange leaves in fall. Students and visiting scholars start packing their bags, look around their apartments, and reinterpret half their possessions as junk to be discarded. Walking down the street your eyes catch on cardboard boxes full of books, clothing, and odd bits of furniture. Together my father and I set the couch down amid this miscellany, within view from our second-story window, next to a pile of issues of The New York Review of Books my father had finished reading. We made bets on how long the couch would last. I wondered to what use its next owner would put it. Before the rain arrived, late that afternoon, the couch was gone.

¤

LARB Contributor

Benjamin Aldes Wurgaft is a writer and historian, whose books include Ways of Eating: Exploring Food Through History and Culture (University of California Press, 2023), co-written with Merry White; Meat Planet: Artificial Flesh and the Future of Food (UC Press, 2019); and Thinking in Public: Strauss, Levinas, Arendt (Penn, 2016).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Space Jew, or, Walter Benjamin Among the Stars

If Walter Benjamin had been quicker to flee the Nazis, he might have stood in India during the twilight years of the Raj and experienced the stars...

Writing in Cafés: A Personal History

Benjamin Aldes Wurgaft on writing in cafés.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!