The Memories of Elephants

Violence plays an essential, defining role in novelist Tania James’s stunning second novel, The Tusk That Did the Damage. The novel shines a necessary light on the challenges faced when living alongside the wild.

By Anita FelicelliMay 23, 2015

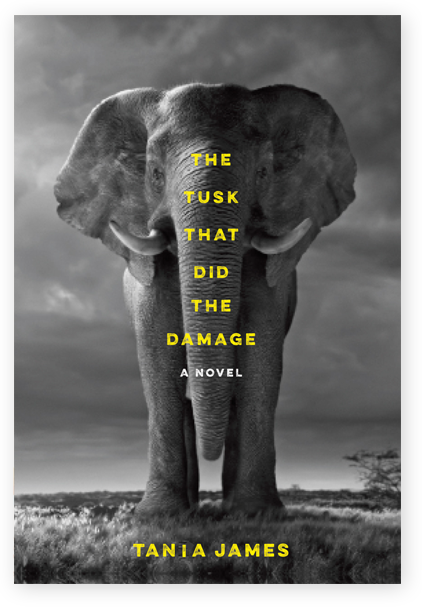

The Tusk That Did the Damage by Tania James. Knopf. 240 pages.

IN THE 1940s, my grandmother moved to a tea estate in Thenmala (literally “honey hill”), in India’s Western Ghats, as a doctor’s bride. The lives of people in the Western Ghats, a hill range that runs parallel to the west coast of India, are inextricably bound up with the lives of wild animals in a way that seems almost fantastic to those of us brought up in the ticky-tacky boxes of the American suburbs. My grandmother has related anecdotes about tigers and peacocks, mynah birds, rabbits, and more.

All of my grandmother’s stories, told in a soprano, lack dramatic conflict, their narrative structure too loose to compel more than images of a more charming, bucolic place and time, but they all evince a way of life entwined with wild animals. There are only minor intimations in her stories that the animals roaming the tea estates were violent in the way that nature sometimes is. I suspect violence isn’t part of her stories because there existed more wild space for animals in the 1940s, and therefore there was much less danger of them coming into human spaces.

As a child from the American suburbs, raised on stuffed animals and anthropomorphic stories and zoos, I took great delight in my grandmother’s animal anecdotes. Stories about the entanglement of humans and wild animals only make the news in America because such encounters are relatively rare. Recently, after two llamas escaped and went on the run in Sun City, Arizona, #llamas trended on Twitter in the U.S. Every few years, a mountain lion wanders into the Bay Area streets only to be captured and sent back to a designated “wild” space. Sometimes we are reminded of our pets’ wild roots when they don’t get along with another animal — when my corgis spot a familiar nemesis in a neighbor’s pit bull, they bark and strain at their leashes, itching for a fight. For the most part, however, our American lives — our suburban sprawl and our industrial activities — have already fully encroached on the wild, pushing many animals’ lives out of the way. Because of this tendency, a number of animals have gone extinct.

Over the last few decades, it has become clear that wild animals pose a danger for villagers in forested areas of the Ghats and even some small cities, and this danger grows ever more threatening as India’s population grows. Traditionally perceived as gentle giants and revered by Indians, elephants have been pushed into smaller and smaller spaces due to development. Lacking sufficient wild space, elephants may wander into human spaces, including villages, cities, and rice paddies, coming into violent and at times fatal conflict with humans. From 1998–2010, captive elephants killed 212 people in the South Indian state of Kerala. Elephant behavior expert Gay Bradshaw has noted that these elephants are being driven to madness by human violence; elephants are reacting the way we would under siege.

¤

Violence plays an essential, defining role in novelist Tania James’s stunning second novel, The Tusk That Did the Damage. The novel deftly braids together three stories told from different perspectives: Manu, a villager whose brother draws him into poaching; Emma Lewis, a young American woman at work on a conservation documentary with her best friend; and the Gravedigger, an orphaned elephant who witnesses the brutal death of his mother at the hands of a poacher who smells of pineapple rot, and ever after terrorizes the countryside.

The Gravedigger’s story is unforgettable. Mostly told from the elephant’s perspective in an intimate third person that is wholly believable and affecting, the Gravedigger’s story begins during his childhood, as he travels with his mother and clan across the countryside of Kerala. His story is interleafed with myths about elephants, such as a tale of how they lost their wings and were gifted (or cursed) with tusks, and the legend of an elephant graveyard. All of this material works together beautifully to give us a unique sense both of cultural attitudes toward elephants and elephant psychology. I haven’t read a writer that has more movingly captured an animal’s perspective on the page.

Of the Gravedigger we learn, “Other memories he kept: running through his mother’s legs, toddling in and out of her footprints. The bark of soft saplings, the salt licks, the duckweed, the tang of river water, opening and closing around his feet.” Poachers disrupt the idyll of his childhood memories, slaughtering his mother and brutally sawing off the tusks of two male clan members for the ivory trade. Shortly afterward the Gravedigger is captured, and he becomes one of several festival elephants, brought out for holidays, weddings, and other special occasions. He develops a strong bond with his pappan, an elephant caretaker known as “Old Man” who was born into the business.

Old Man occasionally uses a long stick to train the Gravedigger in certain commands, cleverly expressed in the text as exclamation marks, “on and on until the Gravedigger could extract a meaning from each ugly note. Left! Right! Stand Still! Kneel! — the last learned by the whack of the stick across his flanks. Pain pulled his mind to a taut and terrible line, its only goal: to do whatever would prevent the pain.” The trauma of his mother’s death and the violence of his training linger in his memory, and eventually after one last trauma, he becomes homicidal. In an absurd but touching detail, after killing his human victims, the Gravedigger “buries” them by covering them with leaves.

The story of Manu, a poacher’s brother and the son of a drunk Keralite farmer, is also an unusual story, and equally powerful. Manu and his cousin Raghu guard the rice fields from elephants at night, by sitting in a palli, a box on bamboo legs in the middle of the field. They wave a lantern at a herd to scare it away, or call the Forest Department to fire rifles. Raghu calls Manu “Styleking,” teases him about girls, and is his constant companion: “We bickered, but there was a comfort to our fuggy odors and the flash of our teeth in the dark. Other times we burrowed into the quiet, each of us privately wondering what kind of future awaited us.”

Manu’s older brother Jayan, drawn to trouble, becomes a prolific poacher and marries a woman from another village before going to jail for four years for numerous poaching offenses. Six months after Jayan returns home, the Gravedigger kills Raghu. It is a night out in the field guarding crops, a night when Manu is supposed to be with him for safety. Manu’s story touches lightly on divisions among Indians (Jayan’s wife is Christian, Manu’s family is Hindu), and the possibility of a bigger life just beyond a villager’s reach, but at its heart his story is a story of brotherhood and revenge, a story that asks how much we owe our families.

Emma Lewis is a young white American filmmaker who is working with her college best friend Teddy to make a film about veterinarian Ravi Varma. Ravi is an elephant whisperer working on conservation issues in a national park in South India. Her story opens not with her interest in elephants, but with the legend of a road. In the legend, a white Englishman builds a major, dangerous highway after killing the Indian boy who showed him the way through unfamiliar terrain. It’s a compelling setup for the primary themes of Emma’s story: the clash of Western idealism with governmental interests and local needs in the developing world and the collision of modern factual art forms with more traditional values and myths.

Unbeknownst to Teddy, Emma crosses a line and sleeps with their subject, Ravi. Her choice to cross this ethical boundary throws into relief a series of significant boundary crossings in the novel — the one between fact and fiction, the one that separates humans and elephants in the sections about the Gravedigger, and the one created by foresting laws that stop villagers like Manu’s family from cutting timber in the forests as they’ve done for centuries while permitting logging by foreign corporations, as well as the boundaries between humans based on religious or ethnic differences.

Emma’s interest in filming an elephant documentary, we are told, possibly stems from a certain consciousness she sees in the eyes of animals. In one of the most relatable moments in the book, she recounts, by way of explanation, the story of a parakeet given to her by her father for her 15th birthday:

Sometimes I worried that Daisy was depressed, to which my father suggested I put Prozac in her feed, a joke that annoyed me. Why couldn’t Daisy be depressed? Why couldn’t she feel a host of emotions, some of them beyond our explanation? She could fly, so if her body were capable of acts beyond human limitation, couldn’t her mind be capable of emotions beyond our own, like Wing Boredom or Flock Joy or Plummet Buzz, things we couldn’t feel and, therefore, could never understand?

Yet, in terms of drama, the stakes for Emma are fairly low when placed alongside the life-or-death stakes at work in the stories of the Gravedigger and Manu. We know that Teddy’s father is going to cut him off, which makes this documentary, financed by his father, critically important to him, but for all her interesting philosophical musings, we don’t quite know what it is that drives Emma.

Emma’s story has a looser hold for other reasons as well. It’s hard to feel for her entirely when, for instance, she chooses to eat appams (South Indian pancakes made of fermented rice batter and coconut milk), which aggravate her IBS and sends her to the hospital. She manipulates Indians to get better footage for her documentary. A character named “Bobin” makes her think of Batman and Robin. These choices seem true-to-life — “Delhi belly” became a popular term for a reason, and American minds are often filled with popular commercial icons — but Emma clearly lacks the luminous specificity and depth of the Gravedigger and Manu.

¤

Similar themes of cultural clash between Western idealistic do-gooding and South Indian family values were invoked in Tania James’s absorbing first novel, Atlas of Unknowns. In that novel, two sisters from a Kerala village go their separate ways. In order to win a scholarship to study in America, Anju, the younger sister, lies and says she drew a picture actually drawn by her older sister Linno, whose hand was injured in a firecracker accident. Anju’s adventures in America take a turn for the worse when she confides in a boy about her lie. When he exposes her, she runs away.

Although her preoccupations have remained similar, James’s style has changed since her first novel Atlas of Unknowns (2009) and her subsequent short story collection Aerogrammes: and Other Stories (2012). In her earlier books, James stayed mostly in a lyrical, realist register, but sometimes veered toward the sweetly comical or the sentimentally grand. She brings a more sober tone to The Tusk That Did the Damage. Rather than lyricize dramatic moments, she tends to pull back and trust the drama will achieve its own grace without pushing. In a lovely bit, she writes of the Gravedigger in an emotionally bereft state: “With no one to soothe him, the Gravedigger resorted to memory. His mind roamed over the faces and smells he had known as a calf, the flick of a cousin’s tail, the sour-milk smell of his sister’s breath, a pile of elephant ribs still echoing a faint fleshy scent.”

James offers scenes of cruelty that are horrifying, but we never forget that individuals with unique personalities and understandable motivations are the ones committing the violence. She has a true gift for capturing and putting on the page the texture of life in her family’s home state — she is a master of capturing what it actually feels like to be in South India, with its multiple, sometimes competing, class, ethnic, and religious identities and interests, and the tight bonds of extended families. Like Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things, also set in Kerala, The Tusk That Did the Damage has a moral and political awareness, as well as a beauty that should earn it a place in the Asian and Asian American canons.

¤

In the United States, when a wild animal is loose in the suburbs, there is a real likelihood that the animal will be tranquilized or come to some kind of harm, whether it is through the use of rubber darts or the inadvertent violence of a car collision. In South India, as James suggests, there has always been a certain amount of social tolerance for animals, regardless of religion, but that may change. When a mother crow repeatedly dive-bombed the back of my head a few springs ago because her nest was in a nearby tree, I had some hysterical thoughts of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds. I asked my Facebook friends, “Has anyone ever been attacked by a crow?” I received an overwhelming number of responses from my cousins who had grown up in India, and almost none from American friends. My cousins matter-of-factly recounted tales of crows that had attacked them, all of them advising that there was nothing I could do that would make a difference.

The question of elephants attacking humans is, of course, far more serious than a crow’s maternal instincts, but the moral questions around the boundaries of wild space are similar. Some have suggested that it is the human villages in India that need to be fenced in, not the elephants, and it’s an idea at least to be considered.

At the heart of The Tusk That Did the Damage are several interrelated struggles occurring all over the developing world: humans struggling to make a living in difficult conditions; other humans working to preserve animals from habitat loss; and the steady, violent encroachment on wild spaces by humans at large. With moral intensity and abundant grace, the novel soars toward a devastating ending, shining a necessary light on the challenges faced when living alongside the wild.

¤

Anita Felicelli is a writer who studied English, rhetoric, art, and law at UC Berkeley.

LARB Contributor

Anita Felicelli is the author of Chimerica: A Novel and the short story collection Love Songs for a Lost Continent, which won the 2016 Mary Roberts Rinehart Award. Her short stories have most recently appeared in Air/Light, Alta, Midnight Breakfast, and The Massachusetts Review. Her nonfiction has appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, San Francisco Chronicle, The New York Times’s Modern Love, Slate, Salon, and Catapult. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her family.

LARB Staff Recommendations

An Elephant Remembers

John Dixon Mirisola on Tania James's second novel.

To Live Ideologically Is to Narrow Your Life

An Interview with Xiaolu Guo

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!