The Many Worlds of China: On Joshua Kurlantzick’s “Beijing’s Global Media Offensive” and Michael Berry’s “Jia Zhangke on Jia Zhangke”

Yangyang Cheng reviews Joshua Kurlantzick’s “Beijing’s Global Media Offensive: China’s Uneven Campaign to Influence Asia and the World” and Michael Berry’s “Jia Zhangke on Jia Zhangke.”

By Yangyang ChengNovember 18, 2023

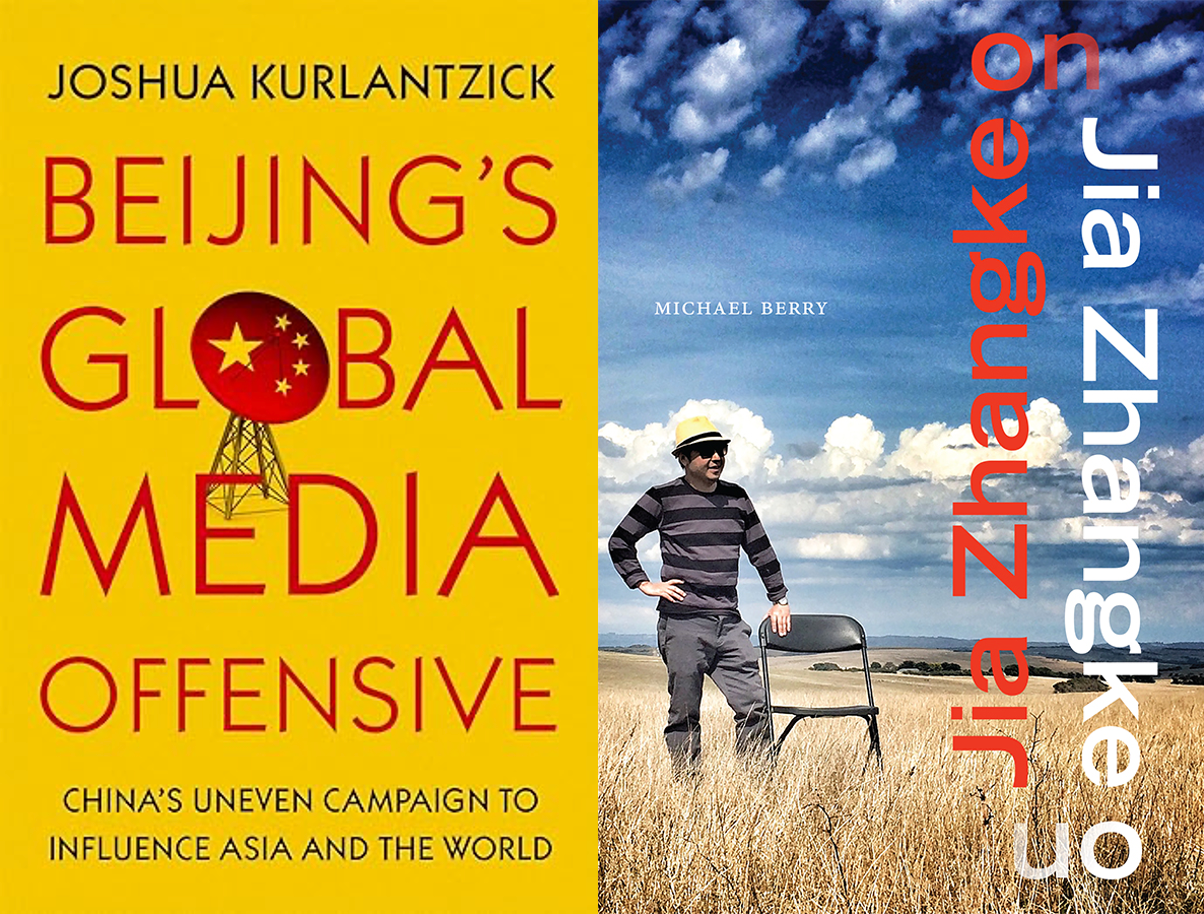

Beijing’s Global Media Offensive: China’s Uneven Campaign to Influence Asia and the World by Joshua Kurlantzick. Oxford University Press. 560 pages.

Jia Zhangke on Jia Zhangke by Michael Berry. Duke University Press. 232 pages.

MY FIRST CENSOR was my mother. I was eight. I had caught glimpses of a Chinese leadership transition on the evening news and excitedly wrote down in my diary the names I had heard, in a mixture of block characters and pinyin. When I opened my journal the next day, the lines had been completely crossed out. Before I could confront her for invading my privacy, my mother sat me down for a scolding. One must never speak of politics, she said, let alone leave a written record. In a voice I had never heard from her before, she sounded more afraid than angry.

I was still learning my native tongue when I stumbled upon its harsh restrictions. In the years that followed, my mother forbade reading and writing outside of schoolwork. The pursuit of the literary arts was considered frivolous and potentially dangerous. When I moved to the United States for graduate school in 2009, I made the leap to advance my physics career, but also with the hope to finally speak freely.

The advent of social media in China led to a blossoming of creative expression in the early 2010s. Then the central government under Xi Jinping re-elevated party control, tightened the official grip on civil society, and became increasingly aggressive beyond the nation’s shores. As the Chinese state flexes its muscles on the world stage and the United States and China appear locked in rivalry, language becomes both a weapon and a battleground. Chinese officials extol the importance of “discourse power.” Editorials repeat Xi’s call to action: “Tell China’s stories well.”

What kind of stories about China are being told? By whom and to what end? This is the subject of two recent books—former journalist and now Council of Foreign Relations senior fellow Joshua Kurlantzick’s Beijing’s Global Media Offensive: China’s Uneven Campaign to Influence Asia and the World and UCLA Chinese studies professor Michael Berry’s Jia Zhangke on Jia Zhangke, both published in 2022. The former can be read as a sequel to Kurlantzick’s 2007 volume, Charm Offensive: How China’s Soft Power Is Transforming the World, which focused on Southeast Asia, the author’s main area of expertise. His new book moves beyond Asia and traditional information platforms to raise the alarm on a wide range of activities connected to Chinese state interests. Its 500-plus pages present an impressive effort on a timely topic, with no shortage of valuable facts and insights. The analysis is nevertheless strained by its sweeping scope and disjointed logic. While covering everything from tourism to international investment, it tends to single out Chinese behavior without adequate context and attributes agency first and foremost to Beijing. In the current political climate, this approach is more likely to stoke fear and provoke overreaction than to foster genuine understanding of China and the world it is part of.

Starkly different in form and approach, Berry’s book is a stunning study of one of China’s most acclaimed filmmakers. Berry was initially drawn to Jia’s work as a graduate student in the late 1990s and first met the director at the New York Film Festival in 2002, where he translated for Jia. Since then, “much of my work has somehow been linked to Jia Zhangke,” Berry writes. Bookended by an incisive introduction by Berry and an afterword by Beijing-based cultural critic Dai Jinhua, Jia Zhangke on Jia Zhangke comprises an extended dialogue between the Chinese director and the American scholar. It relies on interviews conducted over two decades, drawing mostly on ones recorded between 2018 and 2021. The conversation is organized chronologically by theme and divided into six chapters, plus a coda. It starts with Jia’s upbringing and concludes with his latest release, the 2020 documentary Swimming Out Till the Sea Turns Blue. Part autobiography, part foray into film studies, part cultural commentary, it is a richly rewarding read for anyone interested in cinema or contemporary China. The topics of discussion, like the scenes and characters in Jia’s films, are distinctly Chinese yet carry universal resonance.

On-screen and in conversation with Berry, Jia tells stories about China where the country is a real place, in which real people strive to make a living and cope with loss. In Beijing’s Global Media Offensive, by contrast, “China” remains an abstraction created out of cherry-picked evidence and projections that fit a narrative prevalent among the US policy establishment and its allies: China is an “issue” to be solved, a “threat” to be contained. To grasp some of the gravest challenges facing our times, it is essential to understand both versions of “China”: the real country depicted in fictionalized films, and the geopolitical construct imagined by powerful interests.

¤

A Thai princess oversees the construction of a Confucius Institute. Chinese students go abroad to study. Foreign journalists attend training programs in China. Consumers in developing countries purchase Chinese-brand smartphones. In Beijing’s Global Media Offensive, these disparate cases are all part of the Chinese government’s grand strategy to exert influence around the world.

According to Kurlantzick, in the 1990s and 2000s, Beijing sought to present itself as a modest, peaceful, and benevolent power in contrast with the United States. This “charm offensive” achieved some success but ultimately “stumbled,” as evinced by China’s declining favorability in overseas public opinion polls and negative coverage in foreign media. The failure to win hearts and minds, combined with a confluence of domestic and international factors, including China’s growing economic might and democratic regression in the United States and Europe, prompted Beijing to embark on a more aggressive course to project power and shape global discourse.

“China’s expanding influence and information efforts include both soft and sharp types of power—and often both at the same time, in the same country,” Kurlantzick writes. He defines “soft power” as any means of influence outside “strategic, political, informational, and economic coercion or distortion.” While soft power is exercised broadly and in the open, “sharp power” is more concentrated and deployed “in covert, opaque ways”—the “back door” compared to soft power’s “front door.” Throughout the book, Kurlantzick interprets a dizzying array of actions involving Chinese people or entities through these vague and wide-ranging concepts.

The strongest of the book’s dozen chapters are the three that focus on state media. In recent years, Chinese state outlets have expanded to other continents, often with generous government support. Kurlantzick carefully distinguishes different types of Chinese state media that present in different forms, target different audiences, and pursue different objectives. For example, he contrasts China Global Television Network (CGTN) and Xinhua, the Chinese government’s newswire service. CGTN models itself after respectable international broadcasters, especially Al Jazeera, but occasionally takes a page from the more openly provocative playbook of Russia Today (RT). Its foreign bureaus operate with considerable freedom, and the US branch has won awards, including an Emmy. It boasts a global reach of 1.2 billion people, but the actual viewership is limited. Xinhua has enjoyed more success through partnerships with other outlets, a “hyperlocal approach” in covering regions often neglected by global media, and by offering similar content at a lower cost than its competitors like the Associated Press and Reuters. While both CGTN and Xinhua produce quality journalism on issues unrelated to China, the ground shifts closer to home: anticipatory self-censorship can be more prevalent than direct censorship, and straight reporting on other topics lends credibility to state propaganda in the same pages.

This measured analysis of Chinese state media is regrettably muddled as the book moves on to other topics. Much of Beijing’s Global Media Offensive is devoted to illuminating the pernicious effects of Chinese funding, from subsidizing state media to buying up overseas outlets, from donating to educational institutions to contributing to political campaigns. Yet in the latter two cases, few details are given on how the money is used, whose interest it serves, and what the potential drawbacks are. Foreign funding and transnational collaborations at universities often create opportunities and advance inquiry but, depending on the source and conditions, can also restrict academic freedom or compromise research ethics. Kurlantzick claims that Chinese officials and donors have “cultivated” many politicians abroad, including at the state and local levels, and warns that co-option from China “splinters” “democracies’ consensus” toward the country. But which are the democracies and what is their consensus? Should there even be a consensus?

At various points, Kurlantzick seems to imply that a less-than-critical attitude toward China is indicative of being under Beijing’s spell. He also does too little to distinguish Chinese state investment, private Chinese capital, and even funds from foreign citizens of Chinese heritage who do business in China or hold sympathetic views toward their ancestral homeland. The book sounds the alarm on ethnic Chinese political participation in Australia and New Zealand as instances uniquely vulnerable to Beijing’s meddling. This racialized lens inadvertently affirms Beijing’s assertion of blood loyalty and mistakes the victims of Chinese state aggression for its potential perpetrators.

Kurlantzick writes that it is crucial “to determine whether certain Chinese actions are problematic just because China is doing them or whether these actions are inherently bad.” Not only does his book fail to make this distinction, but this statement also implies that Kurlantzick believes Chinese actors can turn an otherwise benign action “bad.” Page after page, “China” is essentialized and made exceptional; Chinese presence is highlighted as a cause for concern.

This exoticizing gaze projects Chinese capabilities onto a different temporal plane: the future. Kurlantzick acknowledges that many of China’s influence efforts have received mixed results, but cautions that “by the end of this decade Beijing is likely to be much more successful,” so countermeasures must be taken now. Conversely, the current hostilities toward China from Washington and its allies, in both policies and rhetoric, are described as the Chinese leadership’s “perception” or even Xi’s “paranoia.” This skewed lens is further evident when Kurlantzick enumerates the “dangerous implications” of Beijing’s influence campaign, that it can harm “other countries’ sovereignty” and—in the same sentence—“the interests of the United States and its partners.” The Chinese leadership, in Kurlantzick’s words, is trying “to displace the United States regionally, in Asia, and globally as well.”

By normalizing US hegemony and foregrounding great power competition, the book discounts the agency of other countries, especially those in the developing world. The book repeats the trope that China is “exporting” repression, as if authoritarianism is a car that can be taken apart and reassembled in a different location. But that is not how governance works. The political and socioeconomic systems in China have been profoundly shaped by the country’s interactions with the rest of the world, and Chinese initiatives abroad are also adaptive to local demands and global dynamics. While Chinese officials and academics have exalted the virtues of China’s model of development, including in overseas venues, the language is used primarily to bolster legitimacy at home and blunt criticism from abroad. A book on Beijing’s information campaign should be better at discerning facts from propaganda.

The reductionist frame in Beijing’s Global Media Offensive overlooks the geopolitical structures and ubiquity of global capitalism that shape both democracies and autocracies alike. Many of the risks to free expression, social trust, and personal privacy that Kurlantzick mistakes as uniquely Chinese or exclusive to authoritarian societies are vulnerabilities caused by capitalist greed and exploitation. Kurlantzick forewarns that if China’s influence campaign succeeds, “rather than globalization and economic interchange making Beijing freer,” then the country will “reshape the world in its image.” But the so-called free market has never cared for the freedom of people. Globalization and economic interchange have already reshaped the world in their preferred image. In the iconic words of Korean film director Bong Joon-ho (Parasite, 2019), “Essentially, we all live in the same country called Capitalism.”

¤

China’s transition from a planned economy to one embracing the capitalist market constitutes a consistent theme in Jia’s films. This artistic focus is deeply rooted in lived experience. Born in 1970 in the central-north Shanxi province, Jia grew up at a place and time of in-betweenness. His hometown of Fenyang was waking up to modernity and, being a county-level town, was “a bridge between the countryside and the cities” as Jia puts it. He caught the tail end of the Cultural Revolution and came of age in the 1980s, “the single most explosive era of social change and individual liberation of the modern era,” according to Jia—which tragically ended with the crackdown at Tiananmen.

Jia, “never much of a good student” by his own account, failed the college entrance exam and began taking art classes in the provincial capital of Taiyuan. There, in 1991, a film changed his life. The directorial debut of Chen Kaige, Yellow Earth (1984) is a majestic portrayal of the rural north in the late 1930s, where the land is infused with histories and songs, the dreams of the peasant, and the elusive promise of revolution. “It was at that moment, after watching Yellow Earth, that I decided I wanted to become a director and my passion for film was born,” Jia tells Berry.

The young man from Fenyang made it to the Beijing Film Academy in 1993 and completed his first full-length feature four years later. The eponymous main character, Xiao Wu, is a pickpocket in Jia’s hometown. Jia attributes the subject choice to his shock at the rapid transformations in the once-familiar place and “the impact the forces of commodification had on people there.” An earlier generation of Chinese filmmakers, including the director of Yellow Earth, had shifted to telling “legendary stories,” which Jia felt were detached from reality. With documentary techniques and the use of nonprofessional actors, Jia wanted to portray “the here and the now.” He trained his camera on the neglected margins of Chinese society—though, as Berry points out, Jia has also pushed back on the very notion of “marginality”: his characters “are ordinary, not ‘marginal.’” Their quotidian struggles “concern the majority of the Chinese.”

In Xiao Wu, the title character stumbles through friendship, romance, and family ties in a world that won’t stop for him. His virtues are as petty as his sins. Jia’s second film, Platform (2000), follows a Fenyang song-and-dance company from the late 1970s through the early 1990s, as the traveling troupe undergoes privatization and its repertoire shifts from revolutionary music to rock and roll. A third film, Unknown Pleasures (2002), which features a pair of disaffected teenagers who try to emulate American gangsters as portrayed on TV, completes Jia’s Hometown Trilogy, which was the subject of one of Berry’s earlier books. Despite critical acclaim and international distributions, none of the three films was officially released in China. Ironically, the forces of commodification Jia depicts on-screen changed his relationship with Chinese censors. As Jia recalls, after 2003, film, once considered “a tool for propaganda,” became “regarded as an industry in China.” The authorities granted Jia and several other underground film directors commercial licenses for their new productions.

I first heard Jia’s name as a teenager, when his 2006 film Still Life won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival. The film follows a man and a woman, unknown to each other, searching for their estranged families in an ancient town that is undergoing demolition, soon to be submerged by the massive Three Gorges Dam project. The process of making the film was a race against the clock.

As Berry writes in the introduction, quoting Dai, Jia invented with Still Life a new visual conception of time and space in Chinese cinema. In earlier films like Yellow Earth, the time of progress and reform is “swallowed by Chinese historical and geographical space.” In Still Life, space maintains its expanse but has lost permanence. Landscapes, natural as well as social, are rewritten by the compressed time of development. In the words of Dai, contemporary China experienced four centuries of European capitalist history in three decades.

Two years after Still Life, Jia turned his lens to another massive government project and the lives around it. Unlike the Three Gorges Dam that left ruins in its path, the aeronautics factory in 24 City was itself in a state of ruin. Established in the late 1950s as Sino-Soviet tensions rose, the military manufacturer was only a shadow of its former self by the end of the Cold War. This film captures the final days of the factory site after the land has been sold to a real estate developer. Workers, some played by well-known actors, share stories of their relationship with the factory. They lament the economic hardship and sacrifice but also express nostalgia for an earlier, simpler era, when material scarcity was compensated for by community and conviction.

In both Still Life and 24 City, as well as many of Jia’s other works, the state is omnipresent but rarely in the foreground. Its power permeates like the weather, embodied in the chalk signs reading “demolish” on the sides of buildings tenants wake up to, mass layoffs and forced early retirements, and voices of official broadcasters. At times, the violence of the state is manifested in its retreat: a cruel indifference to crime and corruption, death, and suffering. The hand that tears down houses also rips apart the social fabric. Lives and relationships become unmoored.

¤

Beijing’s Global Media Offensive veers too often into Cold War binaries: China versus the United States, authoritarianism versus democracy, co-option versus independence. A major part of Jia’s contribution has been breaking down dichotomies. His career contains a multitude of contradictions. He is a darling of global art-house cinema and a successful media entrepreneur in his hometown, a sharp critic of capitalism who has also directed projects for Apple and Prada, a former underground filmmaker who still faces obstacles in obtaining licenses, and a delegate at the National People’s Congress since 2018. He moves through different worlds and is adept at detecting the many tongues.

The final parts of the conversation in Jia Zhangke on Jia Zhangke revolve around language. As Jia tells Berry, “One of the most fundamental questions for a filmmaker is: Does your film have an accent?” The accent of a film can be conveyed in subtle details, like lighting and rhythm; in Jia’s works, the accent is also literal. For his first student production, Jia insisted that his characters speak in their local dialects, despite the official policy to promote standard Mandarin. The reason was simple: he wanted the people on-screen to speak like they would in real life.

This act of linguistic integrity also shatters the notion that there’s only one state-sanctioned voice to speak for China. In a moment of levity in Still Life, an elderly innkeeper repeatedly mumbles “cannot understand” to the visitor from Shanxi. Sometimes, the characters code-switch on-screen, using Mandarin at work and hometown dialects over the dinner table. The shifting of tongues unfurls like a map, traversing space and terrains of power.

Language can delineate but also bridge borders. In The World (2004), Jia’s first official release in China, two performers at a theme park in Beijing, one Chinese and the other Russian, bond and have long conversations despite not knowing each other’s language. For those who have journeyed far from home, the native tongue, like weathered memories, can get lost along the way. The boy in Mountains May Depart (2015) moves to Australia with his fugitive father and takes up Chinese lessons over a decade later. The father, however, resorts to Google Translate to parse his son’s messages in English. The teacher at the Chinese school, a Hong Konger who has emigrated to Australia by way of Toronto, helps interpret a heated exchange between the father and son at the son’s request.

I never learned the dialect of my hometown or that of my grandparents. My mother, who taught elementary school Chinese, took great pride in her unaccented Mandarin. She cleansed any deviation from her daughter’s tongue. These days, when I reach for the sights and sounds of a time and place that only exist in my memory, I often wonder what my relationship with my homeland might have been had I been permitted more freedom with its words.

In Jia’s 2020 documentary Swimming Out Till the Sea Turns Blue, a teenager speaks of visiting his mother’s village in Henan and the questions he wishes he could ask his grandfather: When you were young, did you have enough to eat? Did you want to go out and see the world? A voice from behind the camera asks if the boy could introduce himself in Henan dialect. The 14-year-old replies that, after years in Beijing, he’s forgotten the old tongue.

“Here, let Mom teach you.” After a long silence, a woman enters the frame. The boy repeats after her: “My name is Wang Yiliang. I turned 14 this year. I was born in Henan and grew up in Beijing […] My dream is to become a physicist.”

The woman is Liang Hong, Wang’s mother and one of the writers featured in the film. Swimming Out Till the Sea Turns Blue is a documentary about literature. In it, Jia returns to the countryside to explore Chinese writers’ relationship with land and languages. While the stories in Jia’s films often span years, his latest is the most ambitious in scope: four generations and seven decades across multiple locations. As Jia articulates, “a broad historical canvas” is necessary to truly understand “the inner structures” of Chinese society. A word derives meaning only in context.

The title of the film is a quote from Yu Hua, another writer featured on-screen. As a child in the coastal town of Haiyan, he saw that the seawater was yellow while the textbooks said it should be blue. “One day I decided to swim out till the sea turns blue,” Yu says. According to Jia, this expression encapsulates the spirit of the film and the perseverance of the Chinese people: “So that place where the sea turns blue is the place of our hopes and our ideals.”

Writing, like swimming, begins with a leap of faith. To swim out till the sea turns blue is to leave behind caricatures and clichés, to venture to the edge of understanding and uncover new possibilities. The waters a young Yu Hua swam in are part of the ocean that lies between my homeland and me. Across the vastness, language waves.

¤

LARB Contributor

Yangyang Cheng is a fellow and research scholar at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center, where her research focuses on science and technology in China and US-China relations. Trained as a particle physicist, she worked on the Large Hadron Collider for over a decade. Her essays have appeared in The New York Times, The Guardian, The Atlantic, MIT Technology Review, and many other publications.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Addressing the China Challenge: Realisms Right and Wrong

What does the future hold for US–China relations, and what does it mean to be realistic about that future?

Eating to Live: On Yiyun Li’s “The Book of Goose,” Lu Min’s “Dinner for Six,” and Xiaolu Guo’s “A Lover’s Discourse”

Anjum Hasan reviews three recent novels relating to China: Yiyun Li’s “The Book of Goose,” Lu Min’s “Dinner for Six,” and Xiaolu Guo’s “A Lover’s...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!