The Instagram Artist of Our Time

Eileen Myles’s work has always been both concrete and ephemeral. With Instagram, they've found their medium.

By Madeleine CrumSeptember 19, 2017

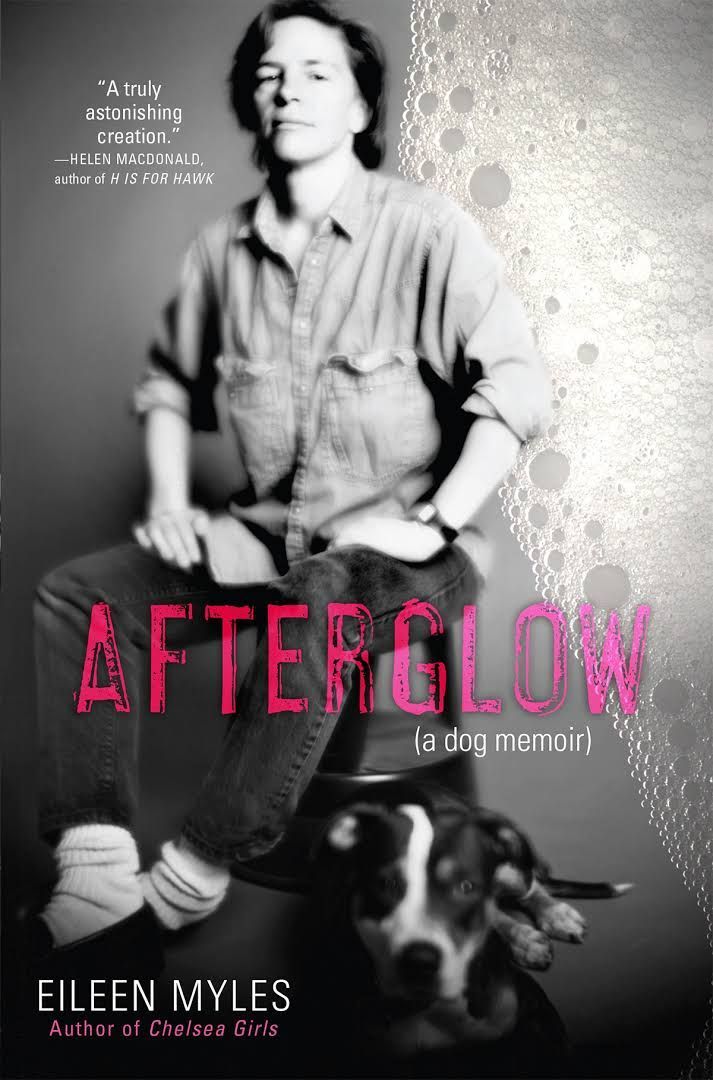

Afterglow by Eileen Myles. Grove Press. 224 pages.

IN 2014, Eileen Myles — poet, art critic, erstwhile presidential candidate — got a pit bull named Honey, a puppy that needed long and frequent walks. They accompanied Honey through the Lower East Side, down Delancey Street, past the river and its bridges. This repetitive task, with its only slight variations, seemed to them like the stuff of Instagram: dailiness, logged and captioned. Myles downloaded the app and has been using it prolifically since.

“Instagram seemed like sort of a companion to this dog-walking,” Myles wrote on The Creative Independent. They post several times most days — what they’re eating, where they’re walking, who they’re with, what they notice.

Those who follow their feed will notice similarities between the writer’s social media activity and their latest book, Afterglow (a dog memoir). Superficially, both turn a loving eye toward their dogs — Honey and Myles’s first dog Rosie. Beyond that, both aim to catalog life in gritty, naturalistic stills that, when amassed over time, form a lyrical whole, like a good grunge song. (Myles mentions their admiration of Kurt Cobain in the book.)

Afterglow, like Myles’s 1994 novel Chelsea Girls, is a series of vignettes, which vary in tone, setting, and point of view. To the extent that there is a central story, it begins when Myles’s parents return their brand-new puppy to its breeder one night, because it barked and whined. Myles equates their childhood desire to own a dog with the want to be seen; decades later, once they owned a dog of their own, they question whether dog ownership is inherently cruel. In the years of her long life, Myles’s pit bull Rosie dragged the poet out of their house and altered their writing; what, Myles wondered, did they provide in return?

There are chapters of the book that meditate on this question, punctuated by transcriptions of videos Myles took on their walks with Rosie. These transcriptions are the most Instagram-like, and the most poignant, moments in the memoir. Rosie eats a burrito; Rosie romps on the beach. She does dog things, but the usual pathos of dog-as-subject is admirably absent from Myles’s portrayal of their pets. In these chapters, and on their Instagram feed, you won’t find a dog framed, posed, or hashtagged for the sake of garnering likes. You’ll find a dog standing, smelling, watching, shitting, and tugging too hard on her leash. By capturing their pets without sentiment, Myles works to bridge the power discrepancies between owner and dog, author and subject, Instagram poster and Instagram liker. And by doing so, they show how the social media platform can be used to connect, rather than isolate.

Instagram is often discussed cynically as a platform designed to gloss over imperfections, and to shill one’s brand. And certainly, it’s been used that way, affecting the places we travel and the foods that we eat, applying to all of it a sheeny filter. But Myles’s aesthetic, which involves repetition and spontaneity, is representative of a kind of Instagram counterculture, one that works against the capitalistic gloss to which the platform is prone.

Of their first forays on Instagram, Myles wrote, “I think that one of the cardinal rules is not to repeat a picture or repeat too close of a picture, or kind of keep trying to fix something or do something.” But Myles enjoys these repetitions: “It seems to me, it’s very musical. The slight variations, just on top of each other, are really interesting.”

On their feed, you’ll find the same beach from different vantage points, and at different times of day. A shadow grows longer; footprints in the sand are eroded by waves. In Afterglow, too, Myles reiterates certain scenes from Rosie’s life, showing how their perceptions shift over time, or while writing. There are moments when Myles thinks of themselves as a cruel pet owner — they neglect to clean the floors and allow Rosie to live with sores on her flank. Later, they reflect that it’s relative; without an owner like Myles, Rosie, a pit bull, might not have been adopted at all.

“I like to make it heavier sometimes. Saying versions of the same thing,” Myles wrote in Afterglow. “You probably already guessed it but I like saying it again. That one little piece again with a twist. And a thud. I don’t feel this way about everything but there are moments that need to be heavy. As a fact. Not an idea.”

These repetitions and riffs can be heartbreaking. Myles looks back on Rosie’s last year, wiping her ass each morning, inconveniencing themselves in order to prolong their dog’s life. By relating the action twice, three times, Myles seems to be writing as an act of reassurance, as if to say: see? I did what I could.

They’re also recapturing the rhythms of their life with Rosie: get up, clean the dog, walk the dog, repeat. Myles’s tendency to repost and repost — or rewrite and rewrite — doesn’t feel listless, or evocative of a sense of ennui. Unlike, say, Kim Kardashian’s Instagram-inspired book Selfish, it’s more than a wry commentary on the performative nature of social media. It’s Myles trying to capture a mood or a memory, to make it concrete, seeable, and accessible by others.

In Afterglow, Myles writes explicitly about their want to sincerely connect — on social media and beyond. The narrator of the book, who is sometimes Myles, sometimes an alter ego, Bo Jean Harmonica, attends 12-step meetings, and remembers the first visit where they felt comfortable chiming in. They were preparing a monologue that they thought would impress; as a poet, they believed their way with words would outshine others’ modes of self-expression. But, they were also worried about Rosie, a puppy who charmed meeting attendees, but who’d wandered off and might’ve been getting into trouble. While fretting about Rosie, Myles opened their mouth to speak. When called on, they mused, unplanned, about their dog’s whereabouts. What was she up to? Had she taken a dump in the corner?

“The room roared,” Myles wrote. “I had shared by vision with them for the first time, the uncollected thought and my wanting and my trying and my desiring was over at last and now finally I was in.” In other words, their spontaneity had a disarming effect on the group, and during that moment of shared laughter, they were connecting, uninhibitedly.

Because their fellow meeting-goers were caught up in a moment of shared imagining — of envisioning the same silly image of the cute puppy making a mess — they were able to momentarily share a creative headspace. Of this phenomenon — connecting through imagining — Myles writes, “We can only open ourselves to the true and actual pictures in our own consciousness and through our participation in this endless corridor we discover at last that we are not alone.”

Myles’s interest in this specific way of connecting explains why Instagram — a medium that allows for vulnerability, and that, with its more capacious caption limit, allows for more than pithiness — suits them.

A self-described introvert who’s recently exploring their more social side, Myles writes in the beginning of Afterglow, “I like the small and large crowds that talk about how they feel. Who listen to one another, who let the collective listening and talking build up a head of swarming energy that fills and delights us. These are the groups that show me that I do like groups.”

These meditations on true social connections versus more artificial ones might seem tangential to a book subtitled (a dog memoir), but Myles threads this idea through their reflections on their relationship with Rosie. How, Myles asks themselves, could their relationship have been less one-sided? How did Myles view their relationship at the time, versus after Rosie’s death? Was Rosie ultimately a means of getting out in the world, of socializing, of connecting with others? Was Myles’s role as dog owner ultimately self-serving?

“I’ve always used my imagining of media as part of my source material in writing,” Myles wrote. “Like, I’ll be on the beach with my dog in 1996, and I’ll just be like watching my dog walk around the beach […] You basically start to have all these thoughts, like you start captioning your dog all the time.”

Their self-consciousness about captioning their pet’s experience is related in one of the above-mentioned transcription chapters, when Myles and a friend film the scattering of Rosie’s ashes into the sea. They feel compelled to record the event, but question what purpose that compulsion serves. Is it for Rosie’s sake, or Myles’s?

“Do you think it’s gross that I’m recording this?” Myles asks.

“You’re an artist,” their friend says. “You have to do it.”

“I could turn it off,” Myles says. “Maybe it would feel better if I turned it off. I’m sure it’s a mess.”

“Nothing wrong with that,” their friend says.

Myles’s choice to include this line of transcription in the book shows they believe spontaneous and often messy recordings are expressive, artistic, and conducive to connection. They seem to draw the conclusion here that Rosie was not exploited by being the subject of Myles’s snapshots and videos; the communal nature of recording and sharing memorializes her in a way that wouldn’t be as weighty if they had done it alone.

While Afterglow can be read as celebration of the tenets of Instagram — offhanded, imagistic self-expression that’s shared widely, and alive in its openness to interpretation — Myles has been writing about these ideas for years, long before the advent of apps.

In Chelsea Girls — as mentioned, written in the same form as Afterglow, in vignettes full of physical descriptions and repeated details — Myles begins one chapter like this: “A roll from the bakery at sixth street with flecks of garlic on the top and a giant glass of ice cold water. A batch of broken merits which Claudia left on the table in the bar last night. Two knives on the table — one for slicing and one for buttering.”

It’s an Instagram-worthy tableau that’s both lovely and expressive of Myles’s specific experiences. Through the image alone, they tell us where they’ve been, and what they might be doing next. It seems, then, that Myles’s writing wasn’t inspired by social media, but rather that with social media — and Instagram in particular — they’ve found a new and worthy medium.

¤

LARB Contributor

Madeleine Crum is a writer in Brooklyn. Recently, she has written for Literary Hub, The Scofield, Vulture, and HuffPost, where she was a books editor and culture reporter. She is from Texas.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Sex and the Sacred Text: Michelle Tea on the Republication of Eileen Myles’s “Chelsea Girls”

I most remember reading "Chelsea Girls" in the dark, at bars around San Francisco in the '90s …

Poetry & Pornography: An Interview with Dodie Bellamy

Matias Viegener talks with poet and novelist Dodie Bellamy about the position of pornography in today’s literature.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!