The Impact of War: Lisa See’s “The Sea Island of Women”

Lisa See's new novel shows how hatred is manufactured, and how fear can turn otherwise compassionate people against each other.

By Rahna Reiko RizzutoMay 10, 2019

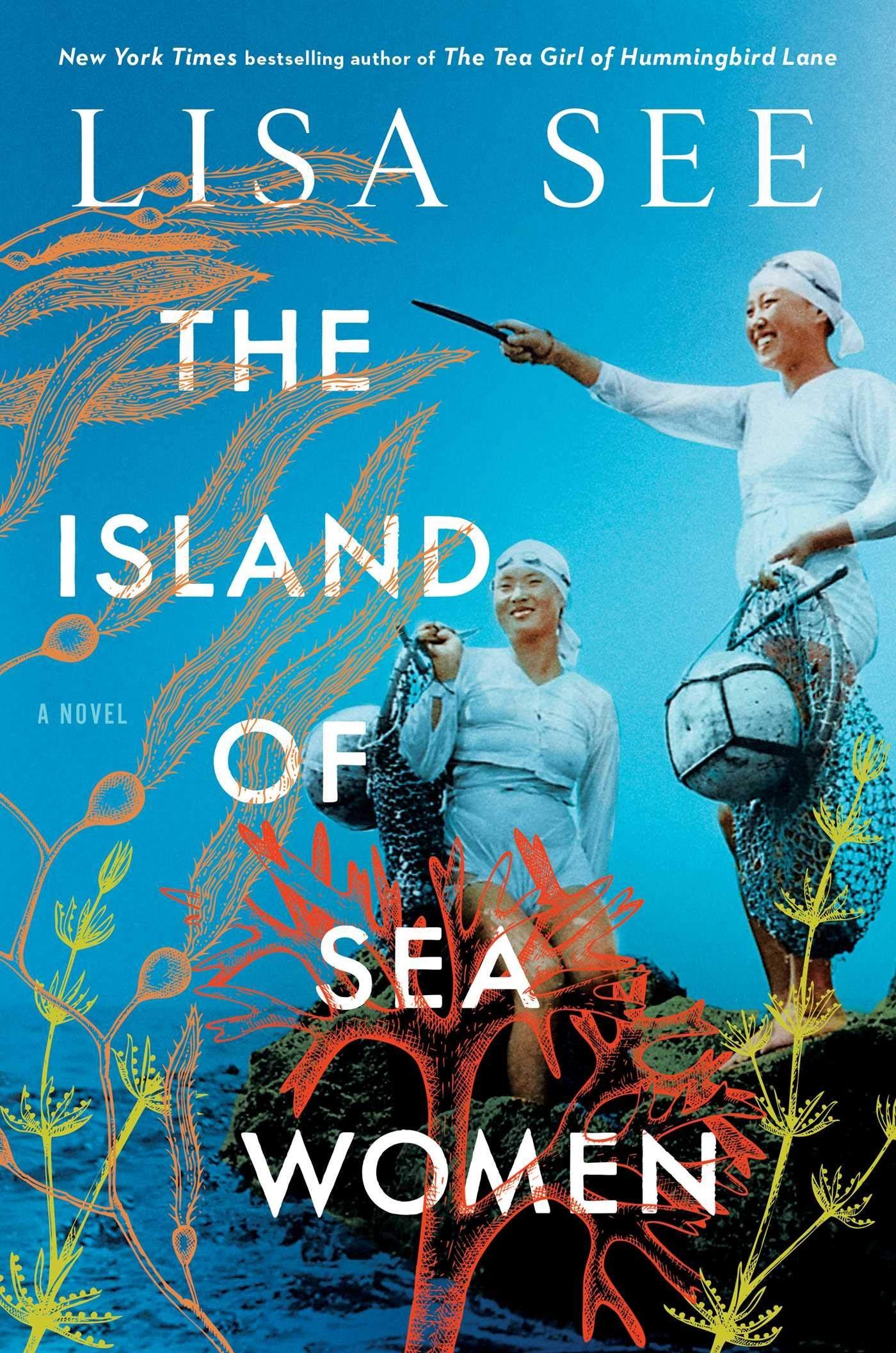

The Island of Sea Women by Lisa See. Scribner. 384 pages.

IT’S BEEN ASKED BEFORE, but what exactly is women’s fiction? The definition according to the Women’s Fiction Writers Association — “layered stories in which the plot is driven by the main character’s emotional journey […] toward a more fulfilled self” — drips with subtext. Descriptors are warnings, created for readers who find stories about people of a different race, culture, sexual identity, societal or physical experience hard to follow, or vaguely discomforting, or simply irrelevant. To describe a novel as “women’s fiction” is to say that female lives are not as interesting, not as necessary or as worthy. But there is no human life in which a woman is not relevant — as a mother, daughter, lover, friend, neighbor, boss, enemy, if not existing purely as a self. There is no life without family, friendship, connection, even if these are disastrous. Nor is there a woman who has lived completely free of a man’s world.

In her latest novel, The Island of Sea Women, Lisa See tackles the notion of women’s fiction head-on. She begins in a familiar way: a not-so-chance encounter on a beach on the remote Jeju Island off the tip of South Korea sets an old woman’s mind on the past; a family of Americans asks Young-sook, who lives on the island, if she recognizes a woman in a black-and-white photograph, and of course she does. See wants us to know this, though Young-sook refuses to acknowledge it. This frame sets up a mystery: Who is the woman Young-sook denied, and why did she lie? What happened between them?

We will find out the girl is Mi-ja, the city-born, orphaned daughter of a Japanese collaborator, who is caught stealing from Young-sook’s family’s fields when she is seven years old, on a day that Mi-ja will later describe as the one of the best in her life. The two girls become inseparable, but before the story of this friendship can unfurl, See must introduce us to a time and place in history that turns the patriarchy upside down. Her challenge is clear: if there was ever a “women’s book,” this is it. On this matrifocal island, women head their households and men watch the babies, make dinner, and wash the clothes. Jeju is home to the haenyeo, all-female village collectives of free divers who tend their “wet fields” as deep as 60 feet in sometimes freezing waters. In 1938, when Young-sook’s memories begin, their collective is led by her mother, who is tasked with training the baby-divers, selecting the harvesting spots, and bringing the divers home safely. The sea is communal, the “mother” embracing an island that was created by goddesses. It is a place of abundance, in which each haenyeo announces herself and her skill through her unique sumbisori, the special “dolphin whistle” that she makes when she comes up for air. See paints a lively scene of the haenyeo singing their gossip, prayers, customs, advice, and rituals back and forth to each other as they row out to dive and back, and their proud “complaints” about their men, whose “weak and idle minds” are excused by the fact that they must “live in a household that depends on the tail of a skirt,” but who are clearly a welcome sight on the shore, where they have brought their hungry infants for the nursing haenyeo to feed during lunch.

This is See’s first book set in Korea, and it is painstakingly researched. There is so much to explain to the modern Western reader, from the Shamanistic rituals to the practical positioning of pigs in this ecosystem, that See must load each sentence in the first sections of the novel with information. We learn much about the island's mythology, reminiscent in shape of a woman’s private parts; we learn the staples of the village diet and what is too precious to eat and must be sold; we learn about lineage and ancestor worship; we become familiar with many aphorisms, such as: “If you plant red beans, then you will harvest red beans.” It takes some patience, though nothing is superfluous; even the history of Jeju, which begins with it bubbling out of the earth and ranges from its initial seafaring ancestors, through the invasion of the Mongols, the conquering of Korea’s kings, and the occupation of the Japanese, carrying within it important messages about foreign occupation. In order to help mitigate this world-building, the author introduces almost immediate dangers. Skipping quickly from their meeting to the beginning of their training as haenyeo, Mi-ja and Young-sook are reminded that “[e]very woman who enters the sea carries a coffin on her back,” a warning that will echo more than once before the novel’s end. As the haenyeo grapple with tragedy early on, their bonds threaten to fracture as See teases what will become a larger theme: how we turn against each other.

The story of Mi-ja and Young-sook’s friendship moves forward against the backdrop of the Japanese occupation of Korea, an ongoing source of bitterness and fear that controls every aspect of village life. The Japanese are “cloven-footed” and known for stealing young girls. Young-sook explains, “We hated the Japanese and they hated us. They were cruel. They stole food. Inland, they rustled livestock. They took and took and took.” Though Japanese notions of beauty and manners are preferred, even by Young-sook, they do not come with protection. Mi-ja is beautiful, “like the clouds — drifting, melting, impossible to catch.” She is educated, pale with perfect skin, a Cinderella figure whose guardians force her to sleep in the granary. But her looks, and her perfect Japanese, do not prevent her from being beaten in the fields by soldiers stealing food. By treading carefully, though, the women escape the worst. Once trained divers, Mi-ja and Young-sook are hired to do “water-work” together in the frigid Russian seas of Vladivostok, first as young women, then again as young brides, a refreshing opportunity for self-sufficiency during wartime.

It is when the girls reach young adulthood that The Island of Sea Women throws off its matrifocal disguise and reveals itself to be the story of men. Now married, Mi-ja to a Japanese collaborator and Young-sook to a childhood friend, the two are parted. The Americans enter the war, and the end comes. The haenyeo lose their autonomy as Western and Confucian male-dominated ways are imposed on the island; they are even banned from the water. Starvation sets in as supplies are blockaded; villagers are punished for sharing what little food they have with refugees; and following the separation of North and South Korea mandated by the terms between the United States and China, resistance to foreign occupation and intervention reaches a breaking point.

Although The Island of Sea Women encompasses both World War II and the Korean War, the true revelation of this novel is the long-unacknowledged conflict between the two named wars, when the already-ravaged Koreans turn against each other in political rebellion and civil war. See powerfully captures the chaos and confusion of the Jeju villagers as the conflict around communism literally sweeps down from the mountains, resulting in the indiscriminate slaughter of innocents known as the Bukchon massacre. The challenge for an author of capturing such a significant and little-known historical event is immense, even if she were to devote an entire book to it, but See is able to convey the horror through the individual, personal, vulnerable human body. During one pivotal scene, a betrayal strips Mi-ja and Young-sook of each other through an act that is initially hard to comprehend. In the aftermath of that decision, though, we come to fully appreciate the author’s exploration of the impact of the choices we make, and of the choices we don’t get to make.

See is most deft when she plays with this line — of betrayal and the impossibility of forgiveness — which she does on a national level as well as a deeply personal one. The Island of Sea Women uses the impact of war on women and children to enable the reader to experience the ways in which colonialism, empire-building, and nationalism destroy communities and countries, but the deeper story is about how hatred is manufactured, and how fear can turn otherwise compassionate people against each other when their own lives are threatened. “We were told we were the lucky ones,” Young-sook comments after being forced to dispose of the bodies of hundreds of loved ones and neighbors. And through that subtle message that no one escapes, and survival may be the harder, greater suffering, See’s firmly established female characters deliver on their true purpose: to help us feel the effects of martial law, military control, and the scorched-earth policies led by men. In doing so, The Island of Sea Women comes full circle from women’s fiction to “just” fiction, and finally to a powerful and essential story of humanity.

Although the novel does not read as an overtly political statement on the divisions we are currently creating among ourselves within the United States, it nonetheless reminds us of how easily we can be made vulnerable, and how quickly we can slip into hating what we fear, or hating what we are told to because we fear. “Should we blame the Americans?” one character asks toward the end of the novel, acknowledging that, even if they did not take part in the slaughter, they watched and did nothing to stop it. See leaves the question unanswered, but it still resonates powerfully today: What will we stand for, how will we separate, harden our hearts, cling to blame? And how will we make the choices that we need to make? As we root for See’s characters to find their way to forgiveness, the answers that will determine our own future are less clear.

¤

LARB Contributor

Rahna Reiko Rizzuto is the American Book Award–winning and NBCC-shortlisted author of Hiroshima in the Morning, Why She Left Us, and her new novel, Shadow Child. She has written for the Guardian, the Los Angeles Times, CNN, LitHub, Electric Literature, Salon, and the Huffington Post, among others.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Korean Pastoral: On Yeon-sik Hong’s “Uncomfortably Happily”

Yeon-sik Hong’s delightful and challenging graphic memoir "Uncomfortably Happily" at once seems to adhere to the Western pastoral tradition and to...

This Is Mother Love in Lisa See’s “The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane”

Diana Wagman on Lisa See's "The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!