The Hope Is That There Was Hope

Libby Flores reviews Deb Olin Unferth's "Wait Till You See Me Dance."

By Libby FloresMarch 31, 2017

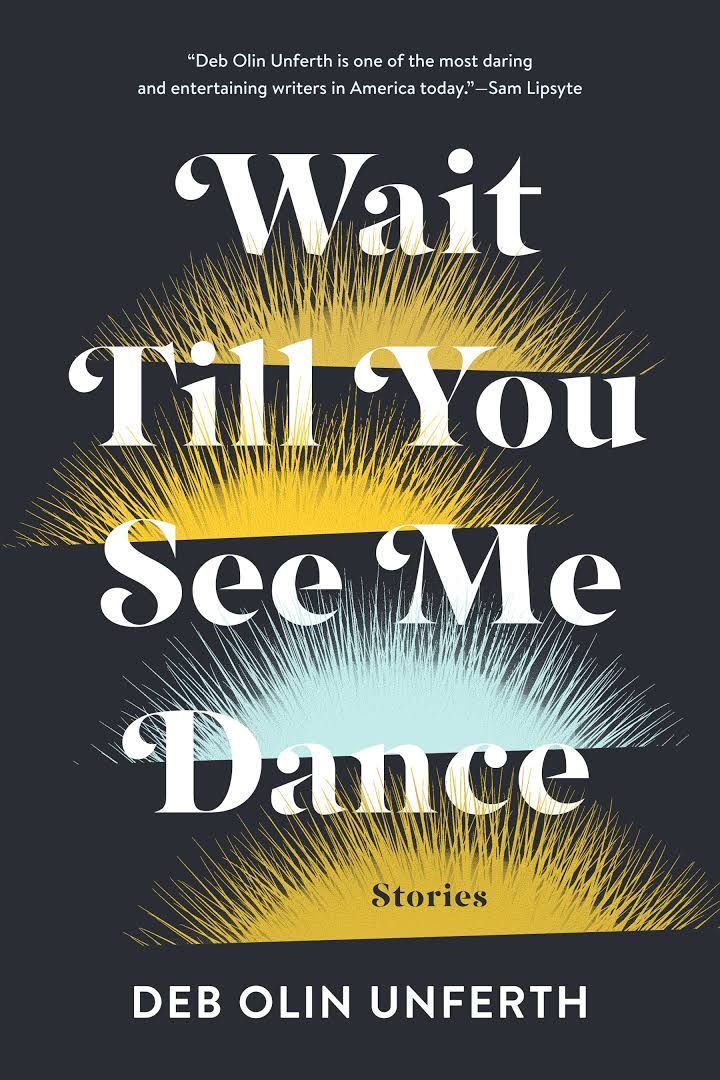

Wait Till You See Me Dance by Deb Olin Unferth. Graywolf Press. 200 pages.

IN DEB OLIN UNFERTH’S STORY “Interview,” one of her characters leaves a word for her future reviewer. The flash piece is a monologue from a writer in an interview for what we assume is a university job:

I can’t promise you that my next book will be published or, if it is, that anyone will read it or like it or like me, or that anyone will review it, or if someone does review it, that they won’t hate it and make humiliating insults that will reflect not only on me and my work, but also on you and your institution (should you hire me).

This kind of flattened, sanguine expectation, humor, and honesty embodies the voice in her new collection of stories Wait Till You See Me Dance. This reviewer did not think of any insults to include. In fact, Unferth’s characters are happy to acknowledge their faults all on their own. These 39 stories circle around you, link elbows, and hold the reader under a strange spell.

The collection is broken down into four sections. For the most part, they seem to delineate the longer more traditional length stories from the short shorts. This collection is her first standalone book of stories; her work was collected and published alongside Dave Eggers and Sarah Manguso in McSweeney’s One Hundred and Forty Five Stories in a Small Box: Hard to Admit and Harder to Escape, How the Water Feels to the Fishes, and Minor Robberies. After just reading Manguso’s 300 Arguments, I can see how they would be a wise pairing.

The prose is spare, and her stories often grin while they expose painful truths so deep in her characters that we are often reminded of the blush of self-awareness. Unferth is also the author of the memoir Revolution: The Year I Fell in Love and Went to Join the War, finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, and the novel Vacation. She is the rare writer who can jump genres not just from novel to memoir to stories, but one that can combine flash fiction with short stories as she does here.

Her people do not look for mercy. These are characters ready to pay for the cost of their sins, and when we meet them they are already running into the fire. An adjunct seeks to save a student and ends up threatening a life in the process; a couple is held hostage exposing simultaneously the art of co-dependency and leaving someone; we sit with a shooter in a parking lot as he contemplates taking a young girl’s life; and a creative writing class plays a game — the one with the most misfortune wins. Danger is always a part of the Unferth landscape, it lurks there in these stories, it elevates them as the ice melts in your glass, it yanks us in, forcing us to recall what subconscious beating fear is plaguing us?

At the start of the title story, the narrator, an adjunct, is asked to an American Indian dance by an annoying office assistant. But the story is really focused on one of the adjunct’s students, a virtuoso pianist. If he fails her class, he will be forced to return to his country, a country she states, “We’d been bombing […] for reasons that had become suspect.” Going home means being drafted, and that he most likely will not make it. Fantastic stakes to put upon a narrator that confesses in the first line of the story, “I know when people will die. I meet them, I can look into their faces and see if they have long to last.” This superpower of hers flits in and out. She can see that her associate chair was “a man whose face held the assurance of the living: he’d hold up a good long while yet.” But when it comes to the student, “The odd thing was, I looked at him, and I couldn’t get a read on him. He could live another month, or he could live eighty more years.” Unferth subverts the reader’s expectations here and throughout the collection. We see a fly ball coming, and she delivers a grounder. The adjunct holds the kid’s fate in her hands, yet her superpower is useless.

The story dramatizes the estrangement of aspiration on many levels. Here the narrator sums up that bottomless feeling of a job that takes more than it gives: “I was what is called an adjunct: a thing attached to another thing in a dependant or subordinate position.”

The story intertwines It’s A Wonderful Life (yes, really), the augur of death, an American Indian dance, how broken the visa/immigration system is (for students specifically), and a version of the butterfly effect. Not to worry, the kid’s fate is revealed at the end, as is the annoying office assistant’s. One of the most stunning moments in the collection is when the adjunct sees her student playing piano for the first time: “I felt like I couldn’t breathe for a moment, like my lungs were being pressed. I saw the emotional deadness in me and I saw it lift. It was temporarily gone.” Such is the beauty of her characters; they are wading in despair, but like a dog at a car window lapping at the fresh air.

At the opening of the story “Stay Where You Are,” an insurgent takes a couple, Max and Jane, hostage somewhere in South America. The couple have been traveling for their entire relationship. “He’d been to fifty-eight countries and never learned a language other than his own […] ‘Besides, everybody speaks English these days.’” This is a quality that irks Jane, as it would most. Traveling together is the only relationship they recognize. Jane muses, “Max the only familiar object for thousands of miles […] It was like being the last two people on earth. It was like you yourself had sent everyone off, except for the man with you — the only man left on earth.”

The lack of fluency in other languages and the years of traveling together, of being a buoy to one another, isolates them and creates what some might call a bond — and others might label co-dependency. You know the rule: if you think you like someone, go on a trip with them, then you can really be sure. But for Max and Jane, vacation is a way of life; it is all they know. To stay in one place would be “what they’d always feared, what they’d always been running from, the drab, the dull, the dumb, and then death.” It is only now that Jane has started fantasizing about going home and getting a job in retail. The normal American life has become exotic to her.

And here they are, hands tied behind their backs. At first, they are unfazed, being such seasoned travelers: “Max and Jane were both determined not to make a thing of it.” We learn that the gunman has a mismatched uniform and ill-fitting shoes. As you step deeper into the forest and into this story, Unferth gives you something to pick up — another detail, clue, characteristic — and as a reader you put it in your backpack.

Throughout the story, the point of view is primarily Jane’s; we get to see more of her inner workings. But then it shifts to Max, and then to our unnamed gunman. As in most good fiction, they all think this is their story. (You do find out whose story it is in the end.) This is where the narrative deepens. Another writer might have just had the stakes stay with the couple, or with Jane. Unferth moves seamlessly, a steady camera on each of these people and their desires. She puts an ear to Max’s heart-wrenching insights, “But he also knew it didn’t matter, for he had already done the one great thing he would do (not travel all over the world, anyone could do that — didn’t even need the resources, just the desire): he’d loved this one woman for eighteen years.”

Once Unferth switches to the gunman’s perspective, the story intensifies. She lists his characteristics in one go: he’d learned how to shoot at nine, he’s always been told he “lacked charisma,” he’d already buried his mother and brothers. He’s suddenly revealed to us anew. She takes him from an archetypal brute to sincere man in a single page.

But it is the next piece of information that tightens the narrative, adding the necessary weight: “One other fact about the gunman: he’d never loved […] He just felt dry. He had desire and lust but never longing, and this bothered him.” To divert and complicate things, she lays down another detail: “he could fall from anywhere and not hurt himself, had been like that since he was a kid, could fall out of trees, off roofs.”

There is Unferth again, putting death right next to love, as well as adding her patented sprinkles of humor. The end execution of this story is a marvel. Everything in the reader’s backpack is employed in a brilliant collision. All three points of view narrow at the climax, as each character must make an onerous choice to see that their yearnings are confronted.

The short shorts in the second and fourth sections are small beams of light. Each directs the reader to the “last call” of emotions. They do what short shorts, flash fiction, micro fiction should do: heighten language, compel us with voice, use a tiny space to make a big impression. The difference between Unferth’s flash fictions and those of other writers is that she often strives for conclusion in a small drop. Her flash fictions execute the hint, the riddle, the tightly pulled knot of a single life. Then, 300 words later, give or take: a splat, or, even better, a new road, or a head turned to a different horizon. The flash sections serve the book well. The approaches vary between the instructional, the observational, the cautionary tale, the joke, and some just run in and leave before you know it. Stand-outs are: “To the Ocean,” “How to Dispel Your Illusions,” “Your Character,” “Fear of Trees,” “Husband,” and “Interview.” I won’t divulge the plots here, not because they do not live as vividly as those of her longer works, but because I don’t want to spoil them. It would be like biting the corners of all the chocolates in the box before you are able to lift the tissue.

The four sections succeed in creating that aforementioned ring around you. There are longer stories that stay with you like “Voltaire Night” and “Bride,” which both whisper of Chekhov’s “story within a story,” and remind you of Carver’s best — extraordinary things happening to ordinary people, all in the name of some broken love. Unferth’s spell is in her absolute confidence and her sublime endings. You lean forward in her stories as the narrative and jeopardy build, but you trust her to get you there.

I believe her to be a harvester of hope in bad weather. Her characters prove this time and time again. A line from the last story in the collection says it well:

So it was with this determination — not quite enthusiasm but the sheer human stubbornness that causes those worse off than he to grab hold and climb back into the world of the living, “optimism,” one might call it — that he snapped the suitcase shut and readied himself for the flight.

¤

LARB Contributor

Libby Flores is a 2008 PEN Center USA Emerging Voices Fellow. Her short fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in Post Road Magazine, Tin House/ The Open Bar, The Guardian, The Rattling Wall, CODA Quarterly, FLASH: The International Short-Short Story Magazine, Bridge Eight, and Paper Darts. She holds an MFA from Bennington College. She lives in Los Angeles, but will always be a Texan at heart. Libby can be found at libbyflores.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Less Ordinary Desperation

Libby Flores on Taylor Larsen's "Stranger, Father, Beloved."

Affective Exchange: Amy Hungerford’s “Making Literature Now”

Louise Hill answers whether "Making Literature Now" is worth your time.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!