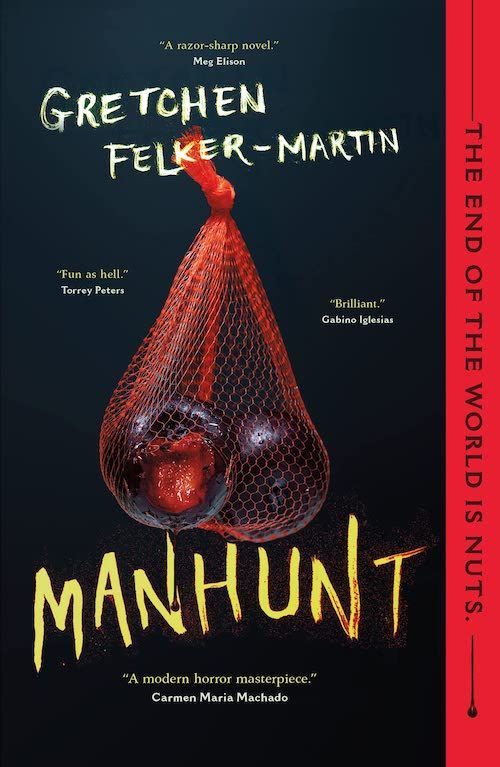

The Future Is Bloody: On Gretchen Felker-Martin’s “Manhunt”

Gretchen Felker-Martin’s “Manhunt” shines a light on how our bodies inhibit us, please us, disgust us.

Manhunt

FEW NOVELS ARRIVE so perfectly in tandem with their moment of release, but Manhunt, the debut novel from Gretchen Felker-Martin, is not like other novels. Released the same week that Texas Governor Greg Abbott called for citizens to report the families of transgender children and Vladimir Putin’s forces invaded Ukraine — and just two months after Parul Sehgal made “The Case Against the Trauma Plot” in The New Yorker — Felker-Martin’s horror novel cunningly weaves trans determinism, war, and trauma together in an effort to locate joy, empathy, and pleasure in a world on fire.

Felker-Martin is a fierce defender of transgressive fiction against the brand of puritan neoliberalism that seeks to limit the genre by leveraging the language of harm, autonomy, and consent. In the year leading up to her debut, she has written about the importance of confronting the horrors of sexual abuse and “the deployment of victimhood as an unimpeachable defense,” all around laying the groundwork for the understanding that art does not harm people — people harm people. Felker-Martin’s critical eye manifests gleefully in her fiction as she dares you to turn away but compels you to keep looking.

Through gruesome bodily description, sharp emotional intuition, and searing sociopolitical criticism, Manhunt is horrifying, at times titillating, and even hilarious — but most importantly, it thrills at every turn. The prose and pacing embody the slow drawback of a bow thrown into release with the shot of an arrow, never missing its target; the building tension of being edged to the pleasure of an orgasm. It not only displays a mastery of horror’s conventions, but it also tears open the rich (and ripe) possibilities of trans horror for the world to see. In a population for whom the remaking of the body and threat of violence is quotidian, the bar for what can be considered scary and thrilling is particularly high, but Manhunt clears it while being hotter than any erotic novel in the post–Fifty Shades landscape and packing in more glittering nature descriptions than Walden.

The novel establishes a lexicon of its own, blended smirkingly with that of the generation of trans women at its center. Beth and Fran, best friends by circumstance, have survived “T-Day,” or the end of the world as readers know it. The estrophaga “t. rex” virus has spread rapidly across the globe, turning anyone with enough testosterone in their blood into flesh-hungry rape machines with ripped skin that oozes pus under the pressure of expanding muscle, scar tissue, and subcutaneous tumors.

Beth and Fran, under the shadow of the Womyn’s Legion, are “vectors”: persons vulnerable to its effects should their T-blocking tactics — namely eating licorice root, spearmint, and balls harvested from the feral men they hunt in the New England wilderness — fall short. Readers meet the pair as they collect balls and cut out kidney lobes to bring back to their shared home with Indi, a cis, fat, widowed doctor, who processes the estrogen to be sold to rich cis women. During a run-in with a militant group of TERFS, Beth’s arrow narrowly misses the throat of the leader, Teach. Ramona — a secret chaser rising in the ranks — returns an equally close misfire, slicing Beth’s cheek open before Robbie, an indigenous trans man, saves her from a pack of men.

The obstacles and vilification of trans women in the real world and Felker-Martin’s apocalyptic one converge, collapsing the extraordinary and the everyday. The novel’s pervasive sense of terror is almost a relief in its sureness: no longer are trans women looking in the eyes of passersby anticipating whether an average day might turn deadly, but rather, they can all but count on any interaction being a fight to the death. There is a thin silver lining: at least now men don’t want to kill them because they are trans; they want to kill them simply because they’re human. “At least he won’t try to make me feel bad before he kills me,” Beth thinks to herself.

The novel’s second act turns to economics in addition to gender politics as Fran, Beth, Indi, and Robbie leave Boston because the lynching of trans women has become common. They accept an invitation to “the Screw,” a luxury bunker run by a teenage heiress, supplemented by the labor of a community encampment living just outside its walls. Here, readers begin to see the subjection of transfeminity determined by aesthetics and attitudes, desirability, and demeanor. Visibly trans Beth finds herself kissing her cis co-worker as they feed some of the compound’s livestock. As a result of the cis woman’s discomfort at her attraction, Beth is reassigned to work as a “Daddy,” a prostitute in male drag to satisfy cishet desires. Meanwhile, Fran is stealthily acting as a liaison to the TERF army and fucking the bunker brat between hits of ecstasy and rounds of Mario Kart after the rich girl promises her a vagina. (“You wanna deal with us? You have to talk to our dickgirl and, like, recognize her humanity,” the bunker princess says in bed.)

At this point, Felker-Martin takes us across more obvious enemy lines to follow Ramona as she leads executions between trysts with a transsexual sex worker. “The Knights of J. K. Rowling” finally have what they sought all along: a biological and undeniable connection between the existence of trans women and the violence perpetrated by the “male” population. Denying health care to trans women as a precursor to amplifying their violent potential is just icing on the cake.

In a scene about halfway through Manhunt, Teach and Ramona stand in a stadium in front of about 200 boys, shrouded in dresses or baggy sweats to obscure the effects of whatever feminizing agents have kept the adolescents from turning. This body in transition terrifies the Legion’s collective conscience and wrecks the binary code they cling to. The cis-ters attempt to pass delusion to the next generation by offering the boys a chance at salvation through service to the womb in the Maenad Corps: guaranteeing access to hormones, orchiectomies, and a permanent designation as a second-class citizen. Or the teens can expect to follow the path of the monstrous thing muzzled in the tarp-covered cage behind the stage, a last-ditch effort to scare the children into subservience.

“Maenad” comes from the Greek maenades, meaning “mad” or “demented,” and mainas, “raving, frantic.” In Greek mythology, a maenad is a female worshipper of Dionysus, the god of wine, fruitfulness, and fertility, known in Roman mythology as Bacchus. Within TERF mythology, godliness is morphed into something divinely (and more importantly, biologically) feminine.

I first discovered the mythology of maenads in the second season of HBO’s Southern vampire drama True Blood, wherein a maenad named Maryann drives the town into a bacchanalia of sex, sacrifice, violence, and even cannibalism — not unlike the prospective lawlessness anti-queer rhetoric imagines as the natural end to accepting and embracing queer individuals.

The lesbian vampire queen of New Orleans unravels one reading of the creatures’ mythology to vampire Bill: “I’m sure you know that everything that exists imagined itself into existence,” she begins. She paints the image of a sad young girl, living at the mercy of masculinity, who then locates a religion that encourages all manner of feminine violence in the spirit of getting closer to the divine.

“Isn’t that delusional?” Bill asks.

Her response: “Never underestimate the power of blind faith. It can manifest in ways that bend the laws of physics or break them entirely.”

I’m reluctant to spend so many words on a show Felker-Martin herself described as “not good” via Twitter, but there’s something to be said for how mythology is melted down and selectively remolded to serve a particular narrative. Felker-Martin nods to this with a juicy bit of post-T-day lore: J. K. Rowling gets mauled in a bunker of her own (probably between glasses of Chardonnay) by a girlfriend with PCOS, which causes spikes in testosterone among people with ovaries.

Maenads in True Blood are deemed mad for worshipping at an altar of a mythical deity. From Teach’s perspective, the maenads of her army are demented by their belief they could one day be women, but it is she who is in the grips of true hysteria. Gender — like the gods the queen speaks of — “only exists in human minds, like money or morality.” Teach’s biological delusion serves as the foundation of her belief that she can build a loyal army out of those she plainly disdains. She has imagined herself as untouchable in the same way trans women imagine themselves as women; the key difference is only one of these beliefs has the ability to materialize. The brunt of her power doesn’t make her divine: it makes her a man in the patriarchal sense. “They’re just men.”

What is ultimately revealed is that fear is not born of trans women or “male-bodied” people being a physical threat to a womyn’s livelihood, virus or no virus; it’s a matter of cis women losing their claim to power above another. For if that counts as a woman these days, what does that say of my self-conception? My power? It’s no coincidence the continued success of both the Legion and the Screw rely on a subjugated class of disposable labor, strung along by the false promise that one day, they too might partake in the riches of the few.

Greater than any achievement in its plot is Manhunt’s ability to dance along the boundaries between the mind and the body, internal experience and outside world, and our senses of pleasure and disgust. The narration hovers in the air of omniscience, brushing up against the thought stream of one character before switching to the another. Indi navigates the physical necessities of her size in the eye of pity and disgust. Beth and Fran hold tight to their womanhood in a world that has cut off the medical possibilities of transition, walking a high wire between regression into the men they were (not to mention the monsters they’ll become) and the political forces that will tokenize them at best and brutalize them at worst. Ramona and Robbie both come undone when their professed politics and intimate desires meet.

Each character whose history and consciousness Felker-Martin explores resists the good-bad binary. The characters we root for make mistakes and enact violence as the characters we are meant to hate (and do) are afforded humanity in spirit and vulnerability of body just the same. Their respective outcomes boil down to their willingness to embrace what Saidiya Hartman calls “waywardness”: “[A] practice of possibility at a time when all roads, except the ones created by smashing out, are foreclosed” and “the untiring practice of trying to live when you were never meant to survive.” Ultimately this “smashing out” allows for one side to triumph while the other fails miserably: the punching out of binary codes, social orders of entitlement, and resignation born of comfort.

The women of Manhunt, often to their own detriment, define themselves in contrast to others: TERF superiority in the face of transness, the Screw’s occupants in relation to the poor campers outside its walls, petite Fran accessing womanliness underneath Beth’s broader frame. Manhunt shines a light on how our bodies inhibit us, please us, disgust us, and women’s preternatural ability to cut each other apart and — should we choose to be so kind — stitch one another back together.

The rhetorical characterization, proximity, and differentiation between the novel’s central pair bring the relativity of womanhood into focus, which can be seen propping up the clarity of any given sentence’s subject throughout. The smaller girl. The other girl. The taller girl. The broad-shouldered girl. The wounded girl. The nose-ringed girl. The older woman. The tired woman. The cis woman. The other woman.

It would qualify as a bona fide writer’s tic if it weren’t necessitated by the nearly all-woman cast. Moreover, under Felker-Martin’s precise pen, no specifier of womanhood is elevated above another. Rather, it’s simply a descriptive account of the breadth encapsulated in the category, subtly driving home the absurdity dripping from any essentialist mouthpiece.

In the same manner that the trans characters of Manhunt look toward one another to make themselves real — to become legible — its cis characters look at trans people and are faced with the falsity of their precious realities. I started hormones shortly before receiving my ARC copy, and in the following months, the fortitude and humor of Manhunt’s trans and fat characters, and the intimacies between them, offered me strength on days when I wanted to curl up behind a door. In a word, it offered me waywardness. Manhunt shows that trans futures, no matter how many of us are killed, will continue to smash themselves out into reality even as the world ends. As rays of light leak through a forest’s ceiling and tender moments glimmer in Manhunt’s surrounding horrors, we will continue to shine through. The proof is on the paper: out of an increasingly devastating reality, Felker-Martin has concocted a world that is infinitely scarier, darker, and bloodier than you can imagine, but still, there is a sliver of hope.

¤

Christ is a writer of nonfiction and criticism based in New York City.

LARB Contributor

Christ is a writer of nonfiction and criticism based in New York City. She is currently an MFA candidate in nonfiction at Columbia University working on a hybrid memoir at the intersection of trans femininity and pop culture.

LARB Staff Recommendations

We Are Monsters: On “Inside Killjoy’s Kastle: Dykey Ghosts, Feminist Monsters, and Other Lesbian Hauntings”

On “Inside Killjoy’s Kastle,” a look at a lesbian haunted house art project as well as the anti-trans clouds that haunt stereotypes about lesbian...

Year of the Werewolf

The werewolf was an apt figure for 1981, a moment when prominent commentators worried that many Americans had become too self-focused.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!