The Formation of a Neo-Nazi: On Sjón’s “Red Milk”

An admirable but unsatisfying account of why a disaffected man might drift toward extremism.

By Randy RosenthalOctober 27, 2021

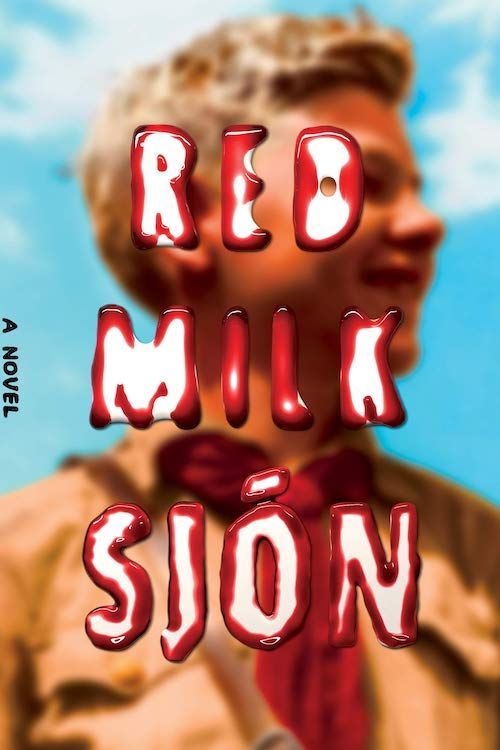

Red Milk by Sjón. MCD. 160 pages.

THE WORLD STANDS at a watershed. The reckoning that began years ago will be the prelude to the end of civilization if nothing is done to prevent it. The omens are obvious to all who have the wit to perceive them. When the dark hour is past, a new day will dawn.

No, these lines are not from a QAnon drop or an alt-right blog, though they easily could be. Rather, they’re adapted from Sjón’s perplexing new novel, Red Milk, which is set in seemingly inconsequential postwar Iceland. Yet the apocalyptic tone and vague content of the above sentences can be applied to any site where extremism rears its head — not only the white supremacist nationalism of the far right, which Red Milk explores, but also fundamentalism on the left, whether it’s radical anti-Zionism or the bizarre antisemitic beliefs of the anti-vax community. In all cases, there is an injustice imagined to be at work — and Jews are somehow behind it.

If you haven’t yet had the pleasure, Sjón is the Icelandic author of The Blue Fox (2003), The Whispering Muse (2005), and From the Mouth of the Whale (2008), three peerless novels that qualify him as one of the world’s greatest writers. Each slim but dense story captures the essence of Iceland’s literary tradition; written with the rhythmic resonance of myth and folktale, Sjón’s sentences are so artistically entrancing that I found myself reading them out loud. Farrar, Straus and Giroux simultaneously published these three books in English, back in 2013, with each translated by the talented Victoria Cribb. The next novel English-reading audiences saw from Sjón was Moonstone (2013), which took a turn toward modernity, being about a queer teenage cinephile navigating the homophobic and flu-ravaged streets of 1918 Reykjavik. This provocative, award-winning novel was followed by an ambitious trilogy topping 500 pages, CoDex 1962 (2018), a work I unfortunately couldn’t get into and didn’t finish. Curious where Sjón would go next, I was delighted to see him tackle the formation of a neo-Nazi with Red Milk — which, at only 135 pages, is as minimal as it is mysterious and disturbing.

The novel begins like a film noir. A body is found on a train, in London’s Paddington Station. Halfway down the first page, we read:

The train arrived punctually — at twelve forty-four — but it has been sitting at the platform for nearly half an hour now, and the passenger in the overcoat has reached his journey’s end in more sense than one. Yet from the mist on the window it is evident that he has not been dead for long — although his head is cooling fast, it still retains a lingering warmth.

Such sentences beam literary perfection. But unlike the author of a crime novel, Sjón isn’t holding back his cards. Policemen search the dead man’s pockets and find that he is 24-year-old Gunnar Kampen, of Reykjavík, and that there’s a swastika on one of his papers. The mystery is not who the man is but why he was in London. Later we learn that the date is August 4, 1962, and from there Sjón jumps backward, to the year of Gunnar’s birth, slowly dropping clues as to how this blond Icelander became one of the country’s foremost antisemites.

In previous books, Sjón has touched upon nationalism and Nordic identity, and the fascist ideology that sometimes arises from the two. Yet he did so with flippant derision and irony, dismissing these elements of Icelandic society (Sjón’s politics are well left of center). But something didn’t feel complete with that approach; as he writes in Red Milk’s afterword: “[T]hinking about it again, I realized that I had yet to explore the matter from a wholly serious point of view. That, in a sense, I ‘owed’ such a book to the victims of the ideology that I had until now satirized and even had fun with.” Sjón’s motivation was personal: the racial theories he mocked were those of his great-grandfather, a leader of “a group of card-carrying Nazi brothers in the Westman Islands.” Without an inkling of his ancestor’s Nazi-sympathizing past, nor any familial fascist influence (the mother and grandmother who raised him were socialists), the eight-year-old Sjón found himself drawing dozens of swastikas one afternoon when he should have been doing homework. It is this combination of shameful silence about a family member with a dark past and one’s own naïve fascination with forbidden symbols that Sjón explores in Red Milk.

The results are an admirable but ultimately unsatisfying account of why one drifts toward extremism and commits oneself to an identity capable of causing mass murder. Don’t get me wrong: the writing is certainly satisfying, as an early line describing a club of ardent cyclists demonstrates: “In pouring rain they sported ankle-length waterproof capes that covered both man and bicycle, flapping around them like the outspread wings of a great black-backed gull.” I say unsatisfying because Sjón deliberately limited his scope, choosing for his subject a man who died before he could make any mark on the world. In other words, there aren’t any dramatic scenes in Red Milk, no speeches full of pathos, no mystical ideologies linking modern fascism to the Nordic pantheon, not even a manifesto. The symbols drop steadily but subtly — a picture of brown-shirted men here, an armband and flag there. But otherwise, Gunnar’s childhood is rather banal. And when he does finally express his views, they’re of the most typical, unoriginal variety: the organization he heads, the Sovereign Power Movement, merely aims to safeguard “the right of the Aryan to cultivate his heritage.”

About halfway through the novel, one of Gunnar’s letters contains a reference to “

A

k

H

naton,” and it takes a relatively astute reader to note that the name refers to Adolf Hitler. The letter revolves around Savitri Devi’s 1952 memoir Gold in the Furnace, a Hindu Nazi’s account of the war, which, along with the writing of George Lincoln Rockwell, Colin Jordan, and Göran Assar Oredsson, “laid the foundation,” as Sjón writes in the afterword, “for the international network of far-right movements as we know it today.” Indeed, when I looked up Gold in the Furnace, the first “review” on Amazon is by “A European Man” who calls the book “a work of beauty and truly awe-inspiring,” refers to “Jewish revenge monsters,” and generally offers a jumble of Nazi sympathizing. In short, these antisemitic ideas are alive and well today.

My first reaction to reading that white supremacist’s unfortunate “review” was to wonder why Amazon hadn’t taken it down, as it clearly promotes hate speech. But then I thought: If Amazon ought to suppress the abominable views of Nazi sympathizers, should Sjón’s novel also be censored? Does giving serious attention to neo-Nazi figures afford their ideas more power, or less? Sjón clearly wants his despicable character to be in some way relatable, which is why he’s made Gunnar so unremarkable. Yet this character, who corresponded with those above-mentioned founders of the modern far right, drew up a list of Icelandic Jews with the implied intention of making sure they were murdered. I was startled to read that one member of that list shared my last name, as did two of the victims of the Tree of Life synagogue massacre in Pittsburgh.

But why? Why kill people because of their last name? That’s what Sjón wants to know, and here is his apparent answer.

Gunnar grew up in a world of uncertainty. He didn’t know why people were protesting Iceland’s joining of NATO, or why Europe seemed to have become a pawn in a larger game played by the United States and the Soviet Union. Things, in other words, did not seem right. Icelanders, along with other Nordics, seemed to have fallen from their glorious and powerful past. There must be a reason for that. And so, Gunnar was nudged here and there; someone dropped a hint, repeated a rumor, provided a model, gave him a paper promoting a conspiracy. And suddenly it all made sense: the culprit is the “Synagogue of Satan.” The Jews have done this — to his people and to the world. Gunnar becomes convinced that Jews are responsible for both communism and capitalism, plotting to dilute the purity of the Nordic blood by encouraging immigration and racial mixing, and that they also use their power over the media and the banking system to pull the puppet strings of the world.

This paranoid template is lifted from The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the fictional (and plagiarized) antisemitic conspiracy story first published in Russia in 1903, which Gunnar mentions about halfway through the novel, in a letter to the editor of the far-right magazine The Dawn. He keeps lending the book to friends, he says, but they never give it back. Despite being debunked a century ago, The Protocols still has a grip on the world, as seen in the deranged conspiracy theories blaming Jews for spreading the coronavirus.

In Red Milk, Sjón doesn’t make these connections explicit; rather, with restraint, he implies that Gunnar’s antisemitic ideas are still prevalent. And instead of seeing Gunnar in action, we mostly get to know him through his letters, a passive approach that leaves me wanting more. Yet this method reflects how most white supremacists present themselves today — via chat rooms and social media. They hide behind the screen, honing their narratives of grievance, justifying their ideologies of hatred, and slowly preparing for the day of reckoning, the watershed moment, Day X, typing and typing until their words will become actions, and violence will be unleashed on their enemies, Jews and gentiles alike.

¤

LARB Contributor

Randy Rosenthal is the co-founding editor of the literary journals The Coffin Factory and Tweed’s Magazine of Literature & Art. His work has appeared in numerous publications, including The Washington Post, The New York Journal of Books, Paris Review Daily, Bookforum, Harvard Divinity Bulletin, The Daily Beast, and The Brooklyn Rail. He is a recent graduate of Harvard Divinity School, where he studied religion and literature, and currently teaches writing classes at Harvard.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Norway, Somalia, and the Specters of Terror

A British filmmaker and a Somali novelist explore migration, radicalization, and terror.

The Whole Human Tapestry: Sjón’s Sprawling “CoDex 1962” Trilogy

Katharine Coldiron decodes Icelandic author Sjón’s “CoDex 1962,” a “risky, funny, sexy, entirely unique book.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!