The Fiction of Rational Miracles: On Amit Chaudhuri’s NYRB Classics Reissues

Saikat Majumdar reviews NYRB Classics’ rerelease of Amit Chaudhuri’s first three books.

By Saikat MajumdarMay 14, 2024

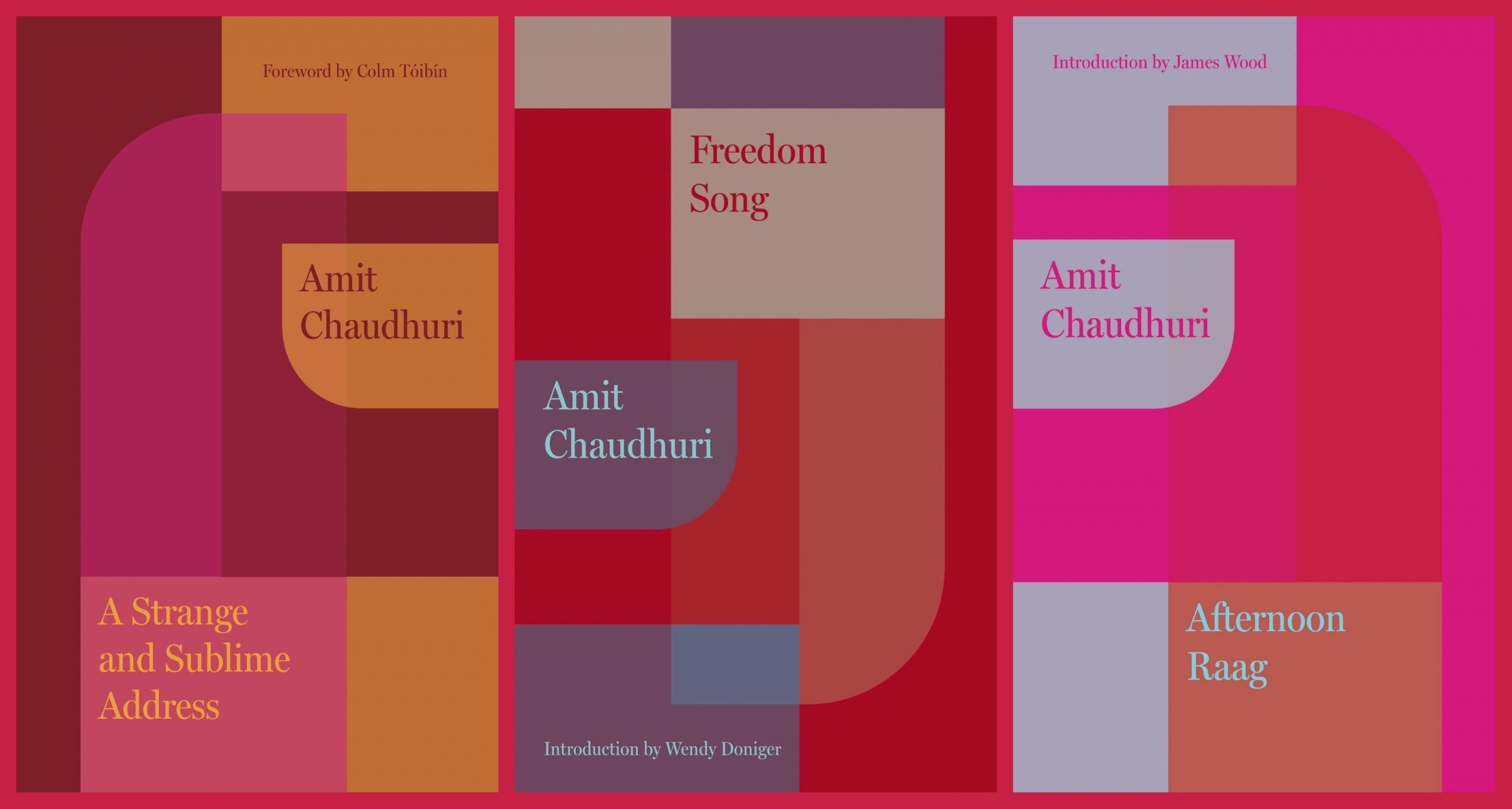

A Strange and Sublime Address by Amit Chaudhuri. NYRB Classics. 264 pages.

Afternoon Raag by Amit Chaudhuri. NYRB Classics. 192 pages.

Freedom Song by Amit Chaudhuri. NYRB Classics. 256 pages.

I READ A Strange and Sublime Address, Amit Chaudhuri’s debut novel, for the first time as a high school student a year or two after it came out in 1991. The novel’s depiction of Calcutta in the early 1970s, by then darkened by the second decade of dysfunctional communist rule, still felt possible as a memory. Reality can take a long time to change even a little in our city. The holiday, the going away to another place that Chaudhuri has often identified as a central theme of his fiction (it returns as the stint of the visiting writer in his latest novel, 2022’s Sojourn), is the narrative precondition of A Strange and Sublime Address. Away from the rhythm of work and school life in the busier, more prosperous Bombay, the novel’s boy protagonist, Sandeep, marvels at the languorous pattern of extended family life in Calcutta. The story is born out of the delightful, idiosyncratic ethnography of the child’s observations.

Earlier in 2024, my son turned 10, about the same age as Sandeep. My son, along with his 14-year-old sister—both of them California-born residents of Delhi for the last seven years—return to Calcutta every year with us for a few weeks, either in the summer or the winter, sometimes during both seasons. While rereading A Strange and Sublime Address, I couldn’t help but think how far out of reach Sandeep’s Calcutta summers have become to my son, who returns to the city on similar holiday-like stretches. This would not be surprising in most places—half a century, after all, is a long time. The surprise—strange and inevitable at the same time—is crafted by the physically unchanged nature of the old neighborhoods in Calcutta. Sandeep went to an old neighborhood in south Calcutta, and we go to an old neighborhood in the north. The physical contours of the places—the closely huddled houses, the lazy but slyly humming terraces, the sound of street vendors and chattering pedestrians—create the illusion of unchanging times in ways I have not experienced in most other places of the world where I have lived.

But a great difference can be sensed in the fabric of community life, with the family at its heart. Of course, every family is different, with peculiar histories and trajectories of their own. Yet what makes Sandeep’s experience possible—not just the condition of his visit but also the minutest folds and textures of his experience—is the life of his extended family in Calcutta, curiously intimate and delightfully strange at the same time. But for a few deeply entrenched, feudally structured extended families, that peculiar sense of the familial, the sensation of communal togetherness, its rituals and relaxations, have, for the most part, now disappeared in Calcutta. Absorbed in his puzzles, soccer, and character-doodling, my son doesn’t miss it—he has never had much of it anyway, due to the peculiar life trajectory of our own family. But the relative emptiness of a communal life centered on family, partially filled by friends and the many distractions of newer economies and technologies, is a pervasive feature of life in India’s most stagnant, and now most deeply provincial, metropolitan city. Large stretches of the city still look the same as the sites evoked by Chaudhuri’s novel, but the loitering, communal soul of the place is now truly a fiction.

To say that the appearance of these new editions of Chaudhuri’s first three novels—A Strange and Sublime Address, Afternoon Raag (1993), and Freedom Song (1998)—charts three decades of the sharpest change in India, and for the Indian in the world, would be to state a cliché. But clichés have truth in them, if of a tired, lusterless sort. The year of the publication of Chaudhuri’s first book, A Strange and Sublime Address, was 1991, the year the Congress government of India, led by Prime Minister P. V. Narasimha Rao and Finance Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh, initiated the iconic move to “liberalize” the national economy, ending the four-decade-plus postcolonial experiment with a mixed/socialist economy, and opening domestic markets to the world. And in 2024, while we celebrate the republication of these three novels, both India and the United States stare at national elections with the very real possibility of the return of populist dictators. It has been a strange journey for India, Asia, and the world, full of lightning shocks at every turn.

¤

But what does historical change, particularly sharp radical change, do to the style and worldview of fiction? Chaudhuri told me once that a stylistic shift felt inevitable in his third novel, Freedom Song—that the dreamy lyricism of his first two novels just didn’t seem possible in the globalized-liberalized 1990s where the later novel is set. (Full disclosure: Amit Chaudhuri is a colleague of mine in the Department of Creative Writing at Ashoka University, and I have been a speaker in the Literary Activism Symposia he convened there.) Freedom Song had to lose the innocence of the boy-on-holiday in A Strange and Sublime Address and the wondrous aspiration of the university bildungsroman of Afternoon Raag. Freedom Song is set in an India that has witnessed the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya in the North Indian state of Uttar Pradesh by the orchestrated efforts of Hindutva cadres, which unleashed a terrifying era of communal politics in the nation that would, over the next couple of decades, make way for the national dominance of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Wendy Doniger, the American scholar of Hinduism who has faced the volcanic ire of Hindu nationalism due to her deep and probing scholarship, writes the introduction to the new edition of Freedom Song—which we read in a world where Lord Ram, the hero of the Ramayana and the avatar of the preserver-god Vishnu, has now been “restored” in the new temple in Ayodhya. The ancient temple, supposed to commemorate the birthplace of Ram, was destroyed by the invading Mughal monarch, Babur, to build the mosque that was razed to the ground by rallying Hindutva agitators in 1993.

Narrative consciousness in Chaudhuri’s novel, which refers to “the troubles far away in Ayodhya,” often belongs to people, sometimes harmless elderly women, who nurture sharp prejudice against, and fear of, Muslims. One of them, Mini, says “In fact, it was no bad thing that they toppled that mosque,” and her friend, Khuku, promptly agrees: “No bad thing.” The landslide effect of the destruction of that mosque, which led to the long reign of the BJP, has been fueled by absurd fears, such as those that arise in Khuku at the sound of the muezzin close to her house, which wakes her from sleep and “remind[s] her that there were altogether too many Muslims around her.” After the series of bomb blasts in Bombay in 1993 organized by mafia dons who happened to be Muslims, musician Suleiman Hussein—who, Doniger reminds us in her introduction, is the only significant Muslim character in the novel—shows up, looking (in the opinion of Khuku and her ilk) “quite pleased.”

The romantic pulse of the first two novels has been eroded not only by the impending trauma of communal violence but also by the stagnation and failure of the nation’s quixotic attempt at industrial growth. That failure was to become synonymous with Calcutta. Yet in A Strange and Sublime Address, Sandeep looks with a mellow, romantic pleasure on the slowness of life and labor in the city, an idyllic departure from the frenetic pace of life in Bombay. Freedom Song creates a disenchanted world where such failures are sensed by a rational, adult mind, their dysfunction narrated with a despondent clarity, though still not without a resigned humor:

The company had changed hands several times, until now it was owned by the state government, and, after having made losses for many years, was named a “sick unit.” Its loyal machines still produced, poignantly, myriads of perfectly shaped toffees, but that organ of the company that was responsible for distribution had for long been lying numb and dysfunctional, so that the toffees never quite reached the retailer’s shelves. Years of labour problems had sapped the factory and its adjoining offices of impetus, but ever since the Communist Party came to power, the atmosphere had changed to a benign, co-operative inactivity, with a cheerful trade unionism replacing the tensions of the past, the representatives of the chocolate company now also representing the government and the party, and the whole thing becoming a relaxed, ungrudging family affair.

The struggles of class and production are reduced to a happy sham: there is no serious allegiance either to capitalism or revolution; the supposed adversaries are just members of a playfully sparring extended family. The name of that dysfunctional family is Bengal, where communist activism is a languorous aesthetic affair, limited to the distribution of the party mouthpiece, Ganashakti, and the creation and performance of polemical leftist theater.

But what makes itself felt most abruptly in Chaudhuri’s fiction is not what happens by way of plot but the change in tone: romance is quickly, repeatedly, unrelentingly deflated. Take the following exchange in Freedom Song between Nando and Uma, two of the domestic helpers in Khuku’s household:

“What do you think you’re doing?”

It was Uma. Nando had reached forward and transferred an egg from his plate to hers. The egg was more than an olive branch; it was a testimony of his intentions towards her. Love, or something like it, had possessed him.

Uma had stopped eating; her right arm was poised in mid air.

“What do you think you are doing?” she asked again. “You’re lucky I’m not going to throw the egg into that corner”—she gestured with her head—“because I don’t want to dirty the kitchen and upset mashima. But I’ll tell mashima about you.”

The decline in romance seems particularly acute in relationships that aspire to be conjugal, or those that inhabit domestic spaces in a desolate way. When Khuku’s husband, Shib, stays at home through 10 days of curfew, with all businesses and offices closed, their sudden mutual proximity, for Khuku, only heightens the distance between them. It is sheer apathy, particularly on the part of a man who, an unlikely figure at home through the day, is an ineluctable vision of disconnection and disinterest (one that strikes a sore chord in a world that has survived the confinement of a pandemic):

It had been a mixed blessing, this enforced, artificial reunion. It was as if a train they’d been on had halted somewhere unexpectedly and they’d been forced to take a holiday. She’d found that he wasn’t interested in discussing what was happening at all—the riots, the anger; more interested in re-reading old copies of the Statesman which he’d accumulated during the last week in a drawer. How little concerned he was about the silence outside, in which the sound of a single car horn became disconcerting, as he sat all morning reading! Neglecting to shave, even; a grey stubble appearing on his cheeks.

The truth is, he was not used to being at home. And with Bablu away they were less like a couple than a pair of lodgers.

It isn’t that human nature sharply underwent a radical change in postliberalization India—notwithstanding the slow erosion of community that makes me wonder about the holiday experience of my son in 2024. It would be strange to claim that the loneliness of marriage was suddenly sharpened in India in the 1990s, or that the alienness of arranged marriages became somehow more disconcerting. Afternoon Raag is set in the 1980s, Freedom Song in the 1990s. Human nature, even in its most intimate and personal capacity, certainly responds to upheavals in larger political and economic structures and to the shifts in technology that alter the quality of life (Khuku’s—and perhaps also Mini’s—Islamophobia, for example, is clearly rooted in the conditions of 1990s India). But what is more importantly at work is a change in worldview that heightens disenchantment—indeed, that creates disenchantment as a fundamental feature of Chaudhuri’s style for the first time, visible most clearly in the oversensitive and rifted nature of romantic companionship.

But even the disenchanted, in Chaudhuri’s world, is not without promise, fleeting and ethereal as that promise may be. There is still a teasing presence of recognition in an arranged marriage of strangers, such as that between Sandhya and Bhaskar:

And he knew nothing about her. In marrying each other they had in effect embraced the unknown and the inconsequential. To look at, she might have been anyone; sometimes he would notice how her shoulders looked tenderly hunched and rounded when she was sitting down; the next day he checked to see if it was still true, as if reality could not be relied upon not to change at short intervals; during this time everything he saw in her he saw with a child’s guilty and inquisitive eye.

¤

For many readers, the enchantment of the first two novels remains one of the most unique and identifiable elements of Chaudhuri’s fiction. For me, that enchantment lies in the magic of Chaudhuri’s language, the application of the deeply sensory idiom of English modernism to the quotidian texture of provincial life in Calcutta. I found these books at a moment when I’d been searching for my own tradition as an Indian writer, still poised unpredictably between Bengali and English—one a language of the restless, throbbing movement of life around me, the other of a deep and dreamy absorption in books from faraway lands. A vibrant reading life also existed in Bengali, just as English came to fluttering life in films, music, and conversations with friends, in the seamlessly mixed way that languages exist in India. The quotidian life of Hindi was alive in the streets due to the popularity of films and the reality of migration. But the heightened performance of Bengali, apart from its still-secure place in family life, was enacted by a particularly intimate force of culture, writing about which has been a difficult experience for me.

My longing for these two languages, English and Bengali, was rife with contradictions: the colonial language sought to enter private life, while the locally inherited language became one of heightened performance due to unexpected but inevitable forces. A love for the minute textures of domestic and private life, and the unpredictable cracks in their relation with larger public upheavals, had drawn me to literary modernism, especially the work of James Joyce, but also to the writings of a number of women authors, creating a tradition of my own that extended, in time, through Katherine Mansfield, Muriel Spark, and Jean Rhys to Anita Desai, Shashi Deshpande, and Sunetra Gupta. Others would follow. The idiom was teasingly there, and then suddenly out of reach again. The most impossible hurdle was the evocation, in English, of humble local life, with its deep roots in provincial culture. The language of metropolitan modernism, dreamily sensory as it was, evoked the perception of a whole other reality. I had not tasted (or even seen) a madeleine, much the way V. S. Naipaul had never seen a daffodil while growing up in Trinidad—the perpetual problem of the senses that afflicts the English-language writer of nonmetropolitan lineage.

This was the reality within which I first discovered A Strange and Sublime Address, which described mocha, a vegetarian delicacy unique to the Bengali cuisine, in a way that was as physiologically accurate as it was beautiful: “[L]ong, complex filaments of banana-flower, exotic, botanical, lay in yet another pan in a dark sauce.” The gulf Chaudhuri seemed to bridge between language and reality—between the sensual lyricism of Western modernism and the rituals and experiences of provincial India—was a revelation that came with the sensation of a door opening, with fresh air and sunlight touching my skin. No longer did I have to hide vital parts of my self from the glare of the English modernism that had already lit up the interior of my soul. Nor did I have to limit myself to creating characters who listened to jazz and drank scotch, people who existed in real but rarefied spaces in India yet had an outsized literary lineage thanks to the predominance of metropolitan culture in school, college, and even our informal reading canons. The provincial Bengali meal, with its oddly rooted habits, was here to stay in English: “The grown-ups snapped the chillies (each made a sound terse as a satirical retort), and scattered the tiny, deadly seeds in their food.” The long arc of social reality melded seamlessly with the shorter, rhythmic arcs etched by fingers on a plate: “Though Chhotomama was far from affluent, they ate well, especially on Sundays, caressing the rice and the sauces on their plates with attentive, sensuous fingers, fingers which performed a practised and graceful ballet on the plate till it was quite empty.”

In his introduction to this new edition of A Strange and Sublime Address, Colm Tóibín invokes the power of memory as Chaudhuri’s key theme while quoting a similar intimate moment with local food:

Each time he put a small dollop of the yoghurt in his mouth, and chewed on the khoi patiently he tasted his childhood. It was made of the sourness of yoghurt, the sweetness of sugar, and the grey taste of bananas. Also the warmth of his mother’s fingers from which he ate the mixture. It was as if his memory resided in the small, invisible taste-buds in his tongue rather than in his brain.

Such a passage evokes what I find to be the most striking truth in Tóibín’s introduction—Chaudhuri’s preoccupation with “happiness,” which, as the novelist Tóibín knows,

is “the hardest subject of all for the writer of fiction.” Conflict, whether in the public or the private realm, offers the fundamental dynamic for fiction, one that Chaudhuri does not seem to require. Chaudhuri’s conflicts are of the taste of yoghurt on elderly tongues versus the child’s longing, the filament of banana flower now edible in English. Such conflicts, like the sound of a North Indian musical raag with the dissonant soul of jazz, enable the author to float along the calm waters of middle and upper middle class life, eluding the nightmare and spectacle expected of metropolitan novels from the Global South.

“It would have been simple,” writes Tóibín, “in his book to bring in the drama of family conflict or some nightmare images of poverty and destitution.” But that does not mean, Tóibín goes on to say, that the fullness of life captured in his descriptions is based in “nostalgia or sentimentality or false pleading.” It is a remarkable claim that goes to the heart of Chaudhuri’s work—memory without nostalgia. Lodged within the senses, such memory makes the past tangible, never elusive, reminding us that we look, feel, and taste enough, that time is never linear, and that past, present, and future are never quite separable, always playing and hiding within each other.

¤

The calming ripples of memory coursing through bourgeois life in Calcutta are perhaps not what the non-Indian reader expects, looking instead for large macropolitical issues captured in the bright and bold colors of trauma. “For a foreign reader, A Strange and Sublime Address is fascinating,” Tóibín writes, “because it does not dramatize the legacy of Partition, or deal with the caste system in India, or use the novel to enrich our knowledge of large questions of identity and politics. The book normalizes and domesticates what is presented as exotic or even alarming.” The celebration of the ordinary, even the banal, is what carves out Chaudhuri’s place within an unexpected archive of global modernism.

Such a commitment to ordinariness, to the boredom of everyday life, led me to identify a global tradition of modernism in the shadow of colonialism in my 2013 book Prose of the World: Modernism and the Banality of Empire, where I read Chaudhuri’s work alongside that of canonical modernists like Joyce and Mansfield, as well as contemporary postcolonial chroniclers of the politics of the ordinary such as Zoë Wicomb. For his part, Tóibín evokes as parallel the condition of Ireland under late-colonial and postcolonial regimes, summoning the work not only of Joyce but also of more recent chroniclers like John McGahern.

The sheer unlikelihood of the novels Chaudhuri wrote in the 1990s, moreover, must be understood in the context of the genre that dominated Indian English-language fiction in the last two decades of the 20th century. This was the genre of the national allegory, through which Fredric Jameson had theorized the symbolically overdetermined relationship between private and public life in “Third-World Literature in the Era of Multinational Capitalism.” It is certainly true that, during this period, postcolonial nations, perhaps especially India, revealed a great urge to tell the large stories of nationhood, ranging from anti-colonial resistance to postcolonial development. They presented what Tóibín calls the “knowledge of large questions of identity and politics” in bold and spectacular terms, often following the headlines of history and the larger-than-life personalities of Indian politics. English India, it felt in those decades that moved through Nehruvian socialism into the globalized reality of the 1990s, was keen to narrate exhaustive versions of itself on the world stage, particularly through the malleable form of the novel. It was within this powerful zeitgeist that Chaudhuri’s novels started to appear, almost as a willful declaration of indifference to the spectacle of the exhaustive story with high stakes. The stakes in his novels are of a different nature, at once timeless and paradoxical, strikingly captured by James Wood in his introduction to the second novel, writing that “[n]othing much ‘happens’ in Afternoon Raag, though everything is at stake: the homelessness of the self, the working of memory and desire, the music of chance.”

These stakes are “everything” indeed—as they have historically been for the novel. The self, memory, desire, the infinitesimal nature of chance. Wood’s terms remind us that English-language writers far outside the main tradition of the Western novel have recreated the genre so unpredictably that the various anxieties of their remaking—whether in early Naipaul or in the fictitious polemic of J. M. Coetzee’s “The Novel in Africa”—seem mere teasing preludes to the expansive success of the novel in the colonies. This amorphous expansion raises questions about the mythical origin story of the genre that are also inevitably questions about its future. Is the novel born of experience that is local or distant? Is the novelist one who stays at home or goes abroad? Are the quotidian rhythms of bourgeois life the substance of the novel—as Ian Watt would have us believe—or were the “foreign,” the supernatural, and the mythical hidden and subversive parts of its making from the beginning, as Srinivas Aravamudan would later argue? The long history of the novel has finally taught us that there is no real contradiction between these opposites—such are the rational miracles of the genre, which Chaudhuri’s early fictions recapture for us.

LARB Contributor

Saikat Majumdar’s most recent books are The Amateur (2024) and a novel, The Remains of the Body (2024). He wrote the LARB column Another Look at India’s Books from 2020 to 2022. He is the author of four previous novels, including The Firebird/Play House (2015/2017) and The Scent of God (2019); a book of criticism, Prose of the World: Modernism and the Banality of Empire (2013); a book on liberal education in India, College: Pathways of Possibility (2018); and a co-edited collection of essays, The Critic as Amateur (2019).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Storytelling and Forgetfulness

Amit Chaudhuri considers the relation between living, telling, and writing.

On Gravity and Play: In Conversation with Amit Chaudhuri

Amit Chaudhuri on literary activism, alternative modernisms, and the comedy of friendship.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!