The Ecology of Equity, or Why We Need Diverse Voices so I Can Leave My Frida Kahlo Flower Crown at Home

A PEN America Emerging Voices Fellow discusses how today’s young adult fiction handles ethnic diversity.

By Angela M. SanchezMay 11, 2020

EVERY COUPLE OF MONTHS, I get to play the Guess my Ethnicity Game. It only goes one way, and the $64,000 question is me.

If asked delicately, the question usually goes, “Where’s your family from?” With the implicit, or sometimes openly verbalized, addition, “Before Los Angeles.” Another variant is, “What’s your ethnic background?” People who are more upfront with their vulgar curiosity ask, “What are you?” My standard response of “mostly carbon and water” is never a sufficient answer.

When I say that two of my grandparents were from Mexico and two were border-crossed-us Mexican Americans, I get TikTok-worthy reactions. One Lyft driver took his eyes off the road and did a three-quarter-torso-twist double take at me in the passenger seat. Another woman surveyed me, as if I were a scientific specimen, with an exaggerated sweep of her eyes, before declaring, “You don’t look it.”

Ay, lo siento. I’ll make sure to bring my aunt’s serape next time. Will that help me meet your standard of how I’m supposed to look? Let’s explore these assumptions.

I know what they’re seeing. My complexion, while not white, isn’t as rich as my father’s was, and I have light, olive eyes. And people don’t like their biases upended. I might have a strong jaw and nose, which one high school teacher described as “clearly indigenous,” but if I so much as mention that I grew up in Glendale, I’ve had at least one man press, “Are you sure you’re not Armenian?”

I’ve done my 23andMe, I’m sure.

The only people who don’t react this way when I disclose my heritage are people from Mexico. Instead, they take stock of my features and ask, “Who in your family is from Guadalajara?”

You see, while Mexicans — and other Latinx people — can fathom my appearance as part of our ethnic group’s diversity, many non-Latinx Americans have trouble conceptualizing this.

Why? Because a lot of people have a limited notion of what Latinx identity encompasses in this country, thanks in no small part to centuries of (and current-day) racism and the impact it continues to have on our representation in the media. When we’re not being portrayed as cholos or spicy Latin lovers, we’re relegated to the roles of custodial staff, housekeepers, and gardeners — we are The Help.

These stereotypes are not only regrettably alive and well in the 21st century, they are widely endorsed. Take the facepalm fiasco of a novel American Dirt (2020), a project that received a seven-figure advance based on a manuscript that relied on the cliché-riddled plot of a single mother and child fleeing from a cartel run by a Latin lover cut-out. Although author Jeanine Cummins stated that she hoped her novel would inspire her audience to empathy, a story that centers on stereotypes and the sensationalizing of an immigrant experience that is very real and terribly painful for many does more harm than good. Add to this the author’s lack of cultural awareness, much less cultural connection, and the message is clear: Latinxs have but one, definitive narrative, which can be summed up in a couple hundred pages, and someone already told it better than any of us has or ever will.

The community begged to differ. As Latinx authors, academics, journalists, and community members spoke out in protest against Cummins’s stereotypes, the resulting #DignidadLiteraria movement took off. This movement calls for uplifting the numerous and varied narratives of Latinx stories by Latinx writers.

There’s a liberation that comes with having our own voices in charge of the storytelling. Firstly, we don’t write for a white gaze. What does that mean? In her essay “Pure Heroines,” Jia Tolentino shows how whiteness operates as an implicit norm, with an Asian character’s ethnicity “noted by [a] white author as diligently as the whiteness of his or her unmarked protagonist was not.” We don’t need to normalize whiteness or exoticize complexion. And we don’t need to italicize every word in a language that’s been spoken in the Americas longer than English has.

One literary sector that’s made extraordinary headway is young adult fiction. For the past decade, YA authors have been depicting the panorama of experiences that young Latinx readers not only know but deserve to have represented. Recent YA fiction has given us active, heroic Afro-Latinx characters like Sierra Santiago in Daniel José Older’s Shadowshaper (2015) and Xiomara Batista in Elizabeth Acevedo’s The Poet X (2018), which won the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature. Readers have been introduced to Lilliam Rivera’s Margot Sanchez, in The Education of Margot Sanchez (2017), who speaks Spanglish with her family, and Pablo Cartaya’s Marcus Vega, in Marcus Vega Doesn’t Speak Spanish (2018), who (as the title acknowledges) doesn’t speak Spanish at all. Some protagonists struggle with poverty, as does Julia Reyes in Erika L. Sánchez’s I am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter (2017), and some are glamorously wealthy, like Camilla del Valle in Panamanian-American author Veronica Chambers’s The Go-Between (2017).

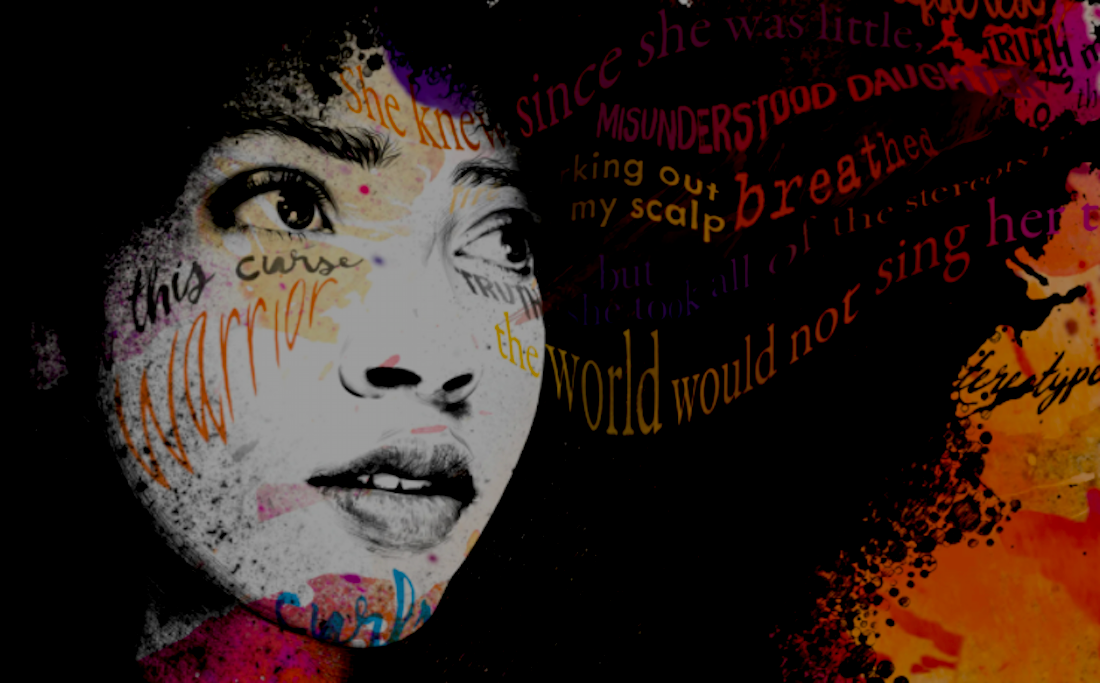

Kid-lit protagonists also reflect an array of heritages, from Mexican and Argentinian to Dominican and Puerto Rican. Latinx identities encompass a vast range of histories and contemporary experiences, including oftentimes marginalized black and indigenous perspectives. This is why our broad representation in literature is so crucial. Not all our stories are centered on pain and trauma. We experience joy, competitiveness, and smug triumph alongside loss, anguish, and despair — and those dark emotions can be in response to something as profound as family separation and sacrifice or as petty as showing up that cabrón at school. We are people. Our community is diverse and complex. Being relegated to a single story distills us down to stereotypes. A graphic anthology I recently reviewed, Tales from la Vida: A Latinx Comics Anthology (2018; edited by Frederick Luis Aldama), recognized that, in order to provide readers with a basic understanding of any community, a wide range of stories is necessary.

This isn’t a condition unique to the Latinx community, either. Anthologies such as Black Enough: Stories of Being Young & Black in America (2019; edited by Ibi Zoboi) and A Thousand Beginnings and Endings (2018; edited by Ellen Oh and Elsie Chapman) capture the experiences, worlds, and mythologies of their respective black and Asian-American contributors. In order to understand — even to merely glimpse — the sheer variety making up these communities, we need more stories written by authors with these diverse identities.

In order to build a critical mass of diverse writers, space must be created for us. PEN America’s Emerging Voices (EV) Fellowship gave me my first taste of what an in-person writing community could be — supportive and nurturing. I had permission to learn. I didn’t feel embarrassed for not knowing that, when someone mentioned Bread Loaf, they weren’t talking about their grocery list, or that Tin House wasn’t some new fad in the tiny-house movement. I was also able to share this space with other writers of color of varying ages and backgrounds. Through EV’s mentor community, which reflected the diversity of my cohort, I was able to glimpse what was attainable. Having my work published no longer seemed out of reach because it was something glamorous that only happened in New York City. Publishing could happen to people who not only looked like me but who also had the varied experiences and identities that have been traditionally locked out of the literary sphere. I felt I could write about the experiences of a Latina high schooler dealing with the impact of gentrification on her family without worrying that my work might be alienating or unrelatable to some readers.

The work Emerging Voices undertakes is critical — and it’s not only relevant to writers. My profession is in philanthropy, with a focus on postsecondary education, another field that struggles with equity. For example, there’s a general misbelief that, if we simply enroll more students of color, we will see more graduates of color. This tunnel vision fails to acknowledge the larger ecosystems in play — faculty, administrators, executive leadership, and campus climate. An administration that better reflects the student body will have a greater awareness of practices that would work best to support specific student populations. Moreover, data has shown that solutions and resources that prioritize students from marginalized backgrounds ultimately benefit the campus as a whole, as opposed to hoping that strategies that generally work for everyone will spell success for under-represented groups.

The same is true in other industries, not the least publishing. The gatekeepers of the publishing industry remain predominantly white and cisgender. If the upper tiers of this pipeline aren’t reformed, the system will only continue to marginalize diverse voices and perpetuate a limited representation of these communities.

According to their 2018 data, the Cooperative Children’s Book Center reported that only about one-third of all children’s books were about people of color while only 21.5 percent were by people of color. The industry promises POC authors that our stories sell, and more are in fact being published, but these are not necessarily stories by us. Latinx authors in particular accounted for just five percent of published children’s books, despite Latinx people comprising 17 percent of the US population. These statistics need to change. Children are highly responsive to seeing characters that look like and represent them. Given these numbers, is it any surprise that, when I first started writing as a kid, I gave my characters names like Heather and Zachary?

This isn’t to say I don’t or won’t ever write about white characters; they simply aren’t my default anymore. With the strides we’re experiencing, especially in young adult lit, I’m hopeful our defaults will evolve overall.

Last fall, I had a meeting with a community partner. He was Latino, a Long Beach native. We got to talking about his high school daughter’s reading list. The crow’s feet at the corners of his eyes bunched up when he said, “I took a peek at some of the books and they have Latinos as main characters now. They don’t cut the slang or Spanglish anymore either!”

I grinned. My colleague was easily a generation older than me and he’s getting to see his daughter grow up with depictions that were always part of his reality but were never on the page. Now that story exists for him, his family, and so many other readers.

He smiled at me and added, “Man, what a time to be alive.”

Don’t we know it.

¤

LARB Contributor

Committed to education and equity, Angela M. Sanchez is the program officer for College Success at ECMC Foundation, a national funder dedicated to postsecondary opportunities for students. Formerly one of the thousands of homeless students living in Los Angeles, Angela completed her bachelor’s and master’s degrees at UCLA, and now serves on the Board of Directors for School on Wheels, Inc., a Los Angeles–based nonprofit that provides academic support to K-12 students experiencing homelessness. Angela is also the author of Scruffy and the Egg, a children’s picture book about family homelessness and single-parenthood.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Big Lit Meets the Mexican Americans: A Study in White Supremacy

Latinx novelist Michael Nava considers the unbearable whiteness of publishing.

Beyond People’s History: On Paul Ortiz’s “African American and Latinx History of the United States”

Paul Ortiz's book helps us remember that the people who fought united against white supremacy, have a long and powerful track record.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!