Beyond People’s History: On Paul Ortiz’s “African American and Latinx History of the United States”

Paul Ortiz's book helps us remember that the people who fought united against white supremacy, have a long and powerful track record.

By Samantha SchuylerSeptember 29, 2018

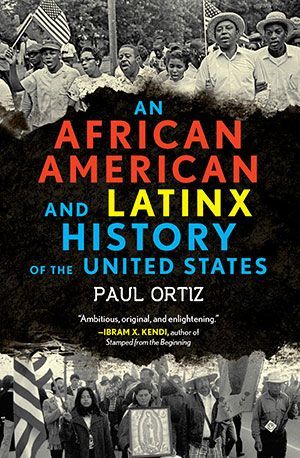

An African American and Latinx History of the United States by Paul Ortiz. Beacon Press. 296 pages.

THE TERM “people’s history” entered into historians’ use in 1966 with E. P. Thompson’s “History from Below,” published in the Times Literary Supplement. Though “people’s history” or “history from below” had both likely been used since the ’30s, Thompson’s work popularized it — inasmuch as a Times Literary Supplement piece can popularize something. This style of historiography subverted the tradition of viewing working people as the passive receptors of historical change — instead, they became actors of their own worth, whose resistance, aspirations, and articulated visions of the future made them active participants in the creation of society today. But Thompson’s work retains the problems of its era: it mixed condescension and glorification of the working man — emphasis on man — and made no real reference to people of color, women, LGBTQ folks. Perhaps most troubling, though, is how the newly minted histories from below assumed, at least among historians, that to take this perspective was in and of itself revolutionary.

Perhaps the best-known example of the genre is Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, going on, as it did, to appear in not only The Sopranos and The Simpsons but the beloved modern-day parable Good Will Hunting. (Though its purported prevalence in high school syllabi is notably overblown.) Zinn’s book is simple, dividing the world neatly into good versus evil, but it is also compelling. Zinn argues that we shouldn’t simply take the perspective of “the people,” recounting the daily toil of the workers with the same reverence as their conquerors’ wars as if this will bring fresh eyes to the human condition, but that to take this perspective asserts that, at its core, human progress as we understand it was designed to benefit a breathtakingly narrow slice of humanity.

And even still, like Thompson’s work and any people’s history, Zinn’s book is necessarily limited, given that the definition of “people” changes over time to better reflect the full range of humanity. But at least a people’s history is more likely to be conscious of its limits — of whom, that is, we count as having a perspective worth reviewing.

Joining this tradition, but also tacitly critiquing the limitations of existing people’s histories, Beacon Press launched in 2011 a series called “ReVisioning American History.” Its fourth and most recent addition, Paul Ortiz’s An African American and Latinx History of the United States, came out earlier this year. A Black Woman’s History of the United States is forthcoming. The books are conceived and written seemingly in the spirit of Zinn’s People’s History, itself published several times by Beacon Press. But while Zinn’s popular text swept through centuries and perspectives under one title, Beacon’s series gives each perspective its own book. Each takes us from pre-colonized America to today from the point of view of queer people, disabled people, Indigenous people, and now African-American and Latinx people.

Zinn’s People’s History is frequently, and reasonably, criticized for casting the American “elite” as a cartoonish monolith, robbing richness and nuance from the struggles of American history. Critics of Zinn have pointed out that historians of the left have written about these struggles with exactly that kind of nuance for decades. And finite space, of course, is the book’s and Beacon’s series’s weakest point: packing centuries of history into a slim 300 pages will always feel rushed and blurred. But its broad focus is also a people’s history’s power — after all, you can find a leftist historians’ perspective in any niche, from the cowboy strikes of the American West to the reformatory prisons for “loose” women that existed across the country from 1910 to 1950. To tackle history’s sweep in its entirety, however, forces the reader to reimagine the past as a whole, unifying the fights for liberty and equality into a continuous struggle. When presented a barrage of activity, you come to see that the struggle has been continuous. Nor has it ended. Viewing the past in this way is not an exercise in history as scholarship. To do so is, as Ortiz writes, America’s “new origin narrative.”

“As we see the policy debate move forward on the left — the jobs guarantee, single-payer, etc. — it becomes clearer and clearer that we lack an organizing synthesis, an ideology, story, and narrative, that brings together, that makes meaning of, these various policies and proposals,” writes Corey Robin. “In the coming years, there is going to be more and more need for this kind of thinking about a central organizing idea for the left, I'm quite confident.” What better unifying narrative than the origin story? The labor, feminist, Black, and Indigenous freedom struggles of the past did not achieve a new world order — if they did, I would like to think that at the very least one percent would not hold half the world’s wealth — but their leaders remain the unacknowledged pathmakers of liberties we take for granted. Meanwhile, it’s normal to tolerate the ongoing push to forget these orchestrators and, what’s more, demonize them. “I was born in 1964 and it was in fourth grade that I remember [racial slurs] being used against me for the first time,” Ortiz writes. He points to a myth that structured his childhood, told to him by teachers and authority figures all his life: Latinx and Black people are, paradoxically, both lazy free riders and cunning thieves who steal jobs, a countrywide conviction that continues today. “I wrote this book because as a scholar I want to ensure that no Latinx or Black children ever again have to be ashamed of who they are and of where they come from,” he writes.

Collectively speaking, African Americans and Latinx people have nothing to apologize for. […] When I was growing up, their struggle was not part of the curriculum. […] No one seemed to know that Haiti was viewed by many of our ancestors as a beacon of liberty during the grimmest moments of our independence wars against the Europeans. […] The descendants of these epic movements are today’s reviled “free-loading” immigrants.

An African-American and Latinx History of the United States is a curriculum as much as it is an ongoing story of liberation. And it does the work of both without resorting to academese, or resembling an academic text at all — to its immense credit. Over the course of the book, Ortiz maps the thought behind and, more importantly, the work of emancipatory internationalism, an idea developed by Black Americans post-revolution that linked the freedom struggles at home with similar struggles happening around the world. Emancipatory internationalists asserted that their rights were intimately connected with the rights of oppressed people in Latin America, the Caribbean, that human progress worldwide was not meant for them. “This was an ideology based on the harsh experience of seeing slavery and racial capitalism extinguishing liberty everywhere it went,” Ortiz writes. “African Americans understood that the United States had torn itself apart due to its allegiance to a theory of profit-based individualism shrouded in slavery. The nation must never again define freedom in such a way as to place property rights above human rights.” It is refreshing to read something that aims to remember history in a way that so clearly poses the question of American identity — who are we, upon whom history has been so frequently enacted? What is our role to play in this ongoing story of struggle?

¤

“Some norms really are more fundamental to liberal democracy than any policy on a social democrat’s wish list,” writes Eric Levitz.

Prohibitions against elected officials disputing the integrity of election results, encouraging political violence, or directing law enforcement to police dissent are more indispensable to self-rule than labor-law reform or universal health care (without such prohibitions, reactionary forces will have little trouble rolling back such left-wing reforms, anyway).

I am certainly not a historian, but even a passing glance through American history shows that the integrity of our elections has not only been disputed before, it’s resolved itself without much change to the system. State-encouraged and -maintained political violence, not its prohibition, is the norm. Elected officials directing law enforcement to police dissent? We can think back to the Chicago Seven, but even as recently as Ferguson, Baltimore’s Freddie Gray protests, Standing Rock: the National Guard has a long history of being mobilized by elected officials to police dissent. Which is to say, Levitz is right: these norms are indispensable to what he calls, either in deep delusion or stinging accuracy, “self-rule.”

Of course this “self” does not constitute all of America. Nor does it speak for the largest nor the most representative parts of the American population. It embodies and speaks for the country’s most powerful, who, despite having the resources and time to conceivably effect some kind of change, will ultimately defend their delusions, protecting the luxuries of their resources and time. For it to work without disruption, it’s important for the failures of liberal democracy to be perceived more as a myth than a truth — phantom pains that can be willed away, if you just acknowledge they don’t really exist.

History creates identity; it is the support system of the “self.” Americans are encouraged to remember the War of Independence as if cutting away from the English monarchy had been a progressive rebellion resulting in greater freedom for “the people.” In reality, the people who gained freedom from the American Independence Movement were white and wealthy men who built a country that maintained the power of white and wealthy men — at the expense of others. (A century later, as Ortiz recounts, the New York Daily News wrote, “If slavery was so great a sin, how comes it that through its agency this country attained the greatest amount of prosperity in the shortest space of time any nation ever attained?”)

Whether or not freedom was meant for anyone other than people like them doesn’t really matter; what really happened doesn’t really matter. It is the past as we remember it that forms the basis of our collective identity. Americans still feel entitled to the identity of revolutionary freedom-seekers, a collective mythology based in a misremembered past — a delusional “self.” And the maintenance of that identity requires muting all others who fall outside its parameters. In this way, Haiti, a country that did shake free from the shackles of slavery to build its own democratic country was not, and is not, granted the same respect and space in public history. After all, the Founding Fathers viewed the Haitian Revolution’s “radicalism” as something to protect America from. America didn’t accept Haiti as a legitimate independent country until 1862, 40 years after France, Haiti’s erstwhile occupiers.

Haiti looms large in Ortiz’s book, and for good reason. It was a “beacon of liberty unlike anything that existed in the United States.” In its wake, American abolitionists saw what a revolution could do: not just protect the interests of the next wave of white men in power, but emancipate. In an 1893 speech, Frederick Douglass began by acknowledging the work of John Brown and William Lloyd Garrison, but added, to the crowd’s applause, “we owe incomparably more to Haiti than to them all. […] I regard her as the original pioneer emancipator of the nineteenth century.” In An African American and Latinx History, Ortiz centers the historically Black emancipatory internationalism movement, which as Douglass expressed drew from the work and writings of Latin American and Caribbean revolutionaries. “Generations of Black and Latinx writers argued that the ability of oppressed people throughout the world to exercise genuine self-determination would strengthen liberty in the United States,” Ortiz writes. “This idea of emancipatory internationalism was born of centuries of struggle against slavery, colonialism, and oppression in the Americas. […] a political culture where the pursuit of liberty outranks nationalism or commercial imperialism.”

Haiti called slavery into question, and Black Americans knew it. As Ortiz recounts, in 1822 Denmark Vesey, a free Black man, organized an insurrection in Charleston, South Carolina, planned for July 14, 1822, Bastille Day. “The liberated slaves planned to escape to Haiti after the uprising,” he writes. “City officials caught wind of the plan ahead of time, and executed Vesey as well as many alleged co-conspirators.” Four years later, a group of enslaved African Americans on a Baltimore the slave-trading ship Decatur bound for Georgia seized control. “After throwing the captain and first mate overboard, the insurrectionists ordered the surviving crew members to steer a course for Haiti and liberty,” writes Ortiz. “Unfortunately, the ship was soon boarded by the crew of a Yankee whaling vessel. The mutineers were seized and brought to New York.”

In 1914, the Wilson administration sent the Marines to Haiti in an occupation that would last 19 years. Shortly after their arrival, they “removed $500,000 from the Haitian National Bank […] for safe-keeping in New York, thus giving the United States control of the bank,” manipulated the 1915 election to establish an unpopular president, and rewrote its constitution to give foreigners landowning rights. All of this is written on the Department of State’s Office of the Historian web page as a historical “milestone.” “There are more stories still,” writes the Haitian-American author Edwidge Danticat in The New Yorker.

Of the Marines’ boots sounding like Galipot, a fabled three-legged horse, which all children were supposed to fear. Of the black face that the Marines wore to blend in and hide from view. Of the time U.S. Marines assassinated one of the occupation’s most famous fighters, Charlemagne Péralte, and pinned his body to a door, where it was left to rot in the sun for days.

Both Haiti’s self-made independence and the horrors of American occupation are rarely acknowledged — their importance, as well as their relationship. This is passive, perspectiveless history’s contribution to the failure of liberal democracy.

“One reason these atrocities are still with us is that we have learned to bury them in a mass of other facts, as radioactive wastes are buried in containers in the earth,” writes Howard Zinn in A People’s History of the United States.

The history of any country, presented as the history of a family, conceals fierce conflicts of interest (sometimes exploding, most often repressed) between conquerors and conquered, masters and slaves, capitalists and workers, dominators and dominated in race and sex. And in such a world of conflict, a world of victims and executioners, it is the job of thinking people, as Albert Camus suggested, not to be on the side of the executioners.

Ultimately, he writes, “We must not accept the memory of states as our own.”

¤

In 1968, when grape workers struck in Delano, California, for better working conditions, El Malcriado (“The Troublemaker”), the newspaper published by the Filipino and Chicano/a farmworker movement United Farm Worker Organizing, created a series of educational workshops in Spanish that were taught to the strikers’ children. They learned about Mexican folklore, art, and the lives of Emiliano Zapata, Pancho Villa, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and “the leaders of the farm workers’ cause.” Their studies were meant to remind children that revolutionary struggle was central to the histories of the people who came before them, and who looked like them. It was not just a way to feel proud about the survival of African Americans and Chicanos in the face of oppression, Ortiz writes, but also “a way to reenvision American history more accurately and more democratically.” After offering tours of Chicago and New York City that focused on sites of slave resistance to friends and family for years, this year prison abolitionist and organizer Mariame Kaba published a self-guided tour. “I do it as an extension of political education that I do in my organizing work,” she told me. During a New York City tour she held last year, a group of eight Black and brown teenagers came along. “Some people warned me in advance that it was likely that I'd have a difficult time holding their attention because social studies is consistently ranked by high schoolers as their least favorite subject,” she said. Instead, they turned out to be her “best audience.” “A couple of the young people approached me later to ask why they hadn't learned any of this information or stories in school.”

A champion for accessible and widespread political education, Kaba later tweeted an excerpt of Robin D. G. Kelley’s essay “Black Study, Black Struggle,” in which he recounts the work of Black feminists Patricia Robinson, Patricia Haden, and Donna Middleton. “Working with community residents of Mt. Vernon, New York, many of whom were unemployed, low-wage workers, welfare mothers, and children. […] they organized and read as a community — from elders to children,” he writes.

They saw education as a vehicle for collective transformation and an incubator of knowledge, not a path to upward mobility and material wealth. […] Their study and activism culminated in a collectively written, independently published book called Lessons from the Damned (1973). It is a remarkable book, with essays by adults as well as children — some as young as twelve, who developed trenchant criticisms of public school teachers and the education system.

As Robinson, Haden, and Middleton wrote in Lessons from the Damned, “All revolutionaries, regardless of sex, are the smashers of myths and the destroyers of illusion. They have always died and lived again to build new myths.”

We must claim a people’s history, telling and retelling and reissuing this claimed history, just as the dominating histories of the people who achieved and maintain the current power structures always have. “In a time of endless war, with democracy in full retreat,” Ortiz writes, we must rediscover and solidify in our collective memory the work of abolitionists, anti-imperialists, slaves who resisted and rebelled and lost, to “chart pathways toward equality for all people.”

“The recovery of these truths,” Ortiz continues, “is more vital than ever as the United States erects barriers to divide humanity from itself in a fit of historical amnesia.” And this is the most urgent part of a people’s history — it unites and empowers in a way that foils the effort of those in power to divide and weaken. When Donald Trump, in an eerie flashback to any number of ethnic cleanses, says to Europe that its immigration policy is “changing the fabric” of the country, that is, “losing your culture,” we need to push back with a knowledge of a past that is not rose-tinted by whiteness. We should remember that the people who fought united against white supremacy have a long and powerful track record. “[P]eople across the hemisphere wove together antislavery, anticolonial, pro-freedom, and pro-working-class movements against tremendous obstacles,” Ortiz writes. “In stark contrast to President Donald Trump’s ‘America First’ approach that involves building a wall between the United States and Mexico, Black and Latinx intellectuals and organizers have historically urged the United States to build bridges of solidarity with the nations of the Americas.”

The old trick that split poor whites and enslaved Blacks loses some of its potency when met with a foundational knowledge of past unity — the history of the people, not the state. This isn’t to take an approach where the champions of liberal democracy and socialist equality shake hands and agree to disagree; rather, it’s to realize that the history we know is not ours. But too many people do know, through experience, that liberal democracy is as unforgiving to them as it is flexible and persistent to all it benefits. This is not the first time someone has thought to do something about it — but the state succeeds when you don’t know, and its official version of history becomes your own.

¤

Samantha Schuyler is a writer and editor living in the American South.

LARB Contributor

Samantha Schuyler is a writer and editor living in the American South.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“A More Beautiful and Terrible History” Corrects the Fables Told of the Civil Rights Movement

Jeneé Darden interviews Jeanne Theoharis about her most recent book, "A More Beautiful and Terrible History ."

Beyond “Carceral Capitalism”

In "Carceral Capitalism," Wang’s essays set up the abolition of the carceral state as one of the key moral battles of this century.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!