“The Cut Is Tangible”: A Conversation with Anwen Crawford

Mireille Juchau talks with Anwen Crawford about her new hybrid memoir “No Document.”

By Mireille JuchauAugust 3, 2022

DURING THE SENSORY MONOTONE of Sydney’s lockdown, I failed to finish several contemporary novels that registered no difference between quotidian matters and violence or suffering. Everyone I knew was one click from COVID death tolls as they filtered Zoom to blur domestic chaos. In literature, I could no longer narcotically scroll. Then I read Anwen Crawford’s No Document (2022) and felt the sharp cut that is part of the book’s compositional strategy. Here was an astute awareness of the violence of particular juxtapositions — refugees and nationalism, borders and the state — and an insight into protest cant like “not in our name.” If we’re made and unmade by documents, as Crawford suggests in her sampling of official reports and state directives, then we can hardly ignore how our own words fall on the page. No Document’s use of white space and lineation, its ethically attuned emphasis, is exhilarating. Its shifting tone is wry, bracing, and affecting.

Crawford, the award-winning writer of Live Through This (Bloomsbury, 2015), is known for her searching essays on music, art, and literature. In No Document, she reconfigures autobiography to elegize a friend who died young and the artmaking and activism so central to this friendship. She lovingly revisits the films, art, music, and beliefs that fired those activities, then pans out to events at the periphery of her life. Poetic connections are drawn between an early film about an abattoir, in which a horse with its forelegs drawn up “recalls a statuary horse on a carousel,” and a circle made by political protesters. Cut to the detention center and 1990s shopping centers, as hallucinatory meanings arise through collage, erasure, allusion.

My conversation with Crawford about this work has been ongoing since I first read it, but what follows took place in May 2022 in Sydney on Gadigal and Cammeraygal land.

¤

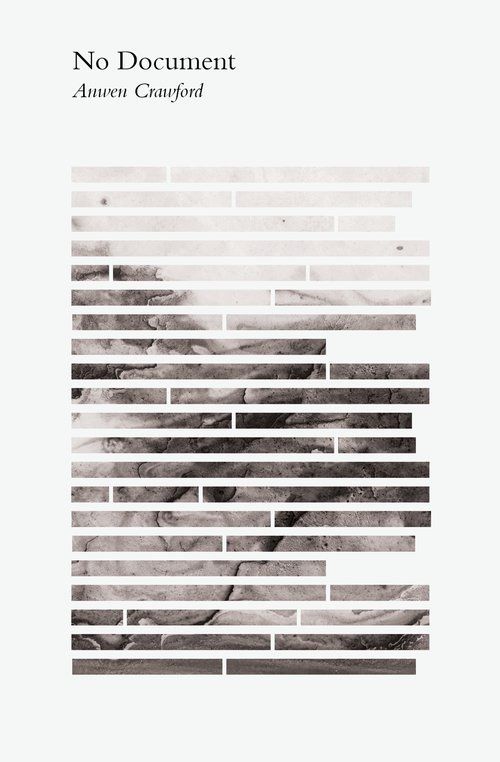

MIREILLE JUCHAU: No Document is described on its jacket as “a book-length essay.” When I began reading, I thought of musical scores, concrete poetry, the cinema. Eight sections, divided by blank rectangles, contain narrative, poems, found materials, collage. I was struck by the precision with which you assign each of your materials its rightful weight. What decisions were involved in composing No Document?

ANWEN CRAWFORD: I wrote No Document as an elegy for a dear friend, artistic collaborator, and political comrade who died in late 2010, at the age of 30, from an extremely rapid and aggressive cancer, the symptoms of which had been masked by his preexisting illness, which was cystic fibrosis. He died less than three weeks after the cancer was diagnosed, and that was a profound shock to me, even though his life, and our friendship and work together, had been formed by the knowledge that he would likely die young. He died so quickly that, even though we were both in the same place, Sydney, I never had a chance to say goodbye to him in person, to hold him when I knew — when we both would have known — that he was dying. And so, the whole impetus, the whole form of No Document, comes, really, out of my saying-it-too-late, saying goodbye into the void, speaking into a relationship that has been gashed, which is partly where the cut comes from, I think, as a primary formal strategy of the book, though I only realize it consciously in answering this question.

It’s been interesting to note the anxiety around genre that this book has produced among some readers, something you allude to in quoting the jacket copy. Maybe this has to do with Australian publishing, where cross-genre or hybrid work has less of a presence than I sense it does in the United States. In both territories, No Document has been framed by its publishers as an essay, though I see the book as having a stronger alignment with poetry than with essay. But the question of genre interests me far less than the question of form, and what formal methods and strategies I had to find that were commensurate with the things I wanted to write about, or write into.

Chief among these was the question of how I could express loss and grief not just on the level of personal bereavement. In trying to honor an artistically and politically collaborative partnership, I also wanted to mark the historical events and losses that we lived through and/or thought through together. At the heart of the book is the question, the problem, and the promise of “we,” both as a political and an ontological category, connected to my sense that none of the historical events the book alludes to, events that have allowed certain “wes” to be constituted in contradistinction to a “them” — wars, border policies, the development of factory farming and the abattoir — are actually over, which is not a new insight by any means.

I immediately thought of Anne Carson’s Nox (2010) as I read your book. She writes:

History and elegy are akin. The word “history” comes from an ancient Greek verb […] meaning “to ask.” […] But the asking is not idle. It is when you are asking about something that you realize you yourself have survived it, and so you must carry it, or fashion it into a thing that carries itself.

No Document feels driven by this kind of urgent asking. You use the second person to address your friend throughout; you withhold his name until the end. Were you conscious of how this intensely private form would be read as a communal object?

I was conscious of it; it was a quality I sought. I think this sense of writing for two readerships simultaneously, intimate and general, comes from zine-making, which was a formative practice for me but is also an ongoing one. (Zine-makers are connoisseurs of the cut: I think it’s true to say I learned to write in part by using scissors.)

But importantly — and this perhaps relates to your sense of the work’s relationship to music, or to sound — I didn’t and don’t conceive of the friend for whom I wrote the book as one of its readers. I conceive of him as the listener, and of the book as an address to him. He can’t answer me, and yet, on some prerational or irrational level, a faith level, I believe that he hears me; I think of the title of Denise Riley’s elegy for her son: Say Something Back (2016). But his writing voice at least is in No Document: there are several quotes in the book from things he wrote to me, letters and postcards and notes. He was dyslexic, so his beautiful, uncanny homonyms — “mourning” instead of “morning,” “aloud” instead of “allowed” — are something I work with, particularly “aloud,” which is how I write, by reading aloud as I go. I also felt that if I allowed myself to address him (aloud) — and I address other people in the book, too, including a child whose death was a direct result of Australia’s border policies — I would feel answerable to him in a vivid, tangible way, and I did. It’s precisely because the dead can’t answer back that I felt I had to say only what I was capable of saying to them.

As for Carson’s “thing that carries itself,” I knew when I started writing the book that it was the only means I had of bringing to a conclusion an artistic partnership that had been cut short (again, here we are with the cut). Our partnership was only ever young and nascent, so in elegizing it publicly I am trying to let the elegy be the “thing that carries” our incipiency, because I couldn’t carry it on my own any longer. This is its final, suspended form.

More of us should write with scissors! Can we return to how the cut functions in No Document as both content and technique? There’s literal cutting — in collaging. There’s an account of self-harm. And a virtuosic opening that splices a scene from Georges Franju’s 1949 documentary Le Sang des bêtes with a wire fence that cuts a gallery space. Franju’s film then shadows other forms of violence throughout — of the state, of capitalism, of institutions, of colonialism.

No Document is an elegy, but it’s also, I hope, an examination of who and what are recognized as worthy of elegizing, which I think is the only kind of elegy my friend would have wanted. I live, as he lived, as a settler on stolen Aboriginal land, land fenced and enclosed, made private property. And the Australian nation that was, that is, brought into being by the dispossession and genocide of Aboriginal people — both ongoing events — is also constituted, in its contemporary sense, by the violent exclusion, the excision from personhood, of refugees who arrive by sea, contemptuously referred to as “boat people.” These intertwined violences, the dispossession of First Nations and the ways in which the nation-state can only exist, can only understand itself, through the exclusionary mechanism of the border, underpin the book because these things underpin Australian life, and because these were things to which my friend and I addressed both our artmaking and our activism.

Montage and collage are both techniques that draw attention to themselves: the compression is felt, the cut is tangible. The cut between and among materials constitutes both a formal and a political argument, so that a work created through montage or collage is always on some level about its own assembly. But I wonder too if this is the (pre)condition of the elegy, to be about its own making: in writing an elegy, one is trying to indicate the dimensions of an absence, but that absence is actually dimensionless, measureless … so the elegy fails, necessarily. The elegy becomes a work about its own failure, and in that sense the formal qualities of No Document were guided by my trying to think through the ethics of writing with or to the dead, while also being guided by both the visual logic of film montage and the formal inventiveness of zine-making.

This “drawing attention” is especially crucial for me in your reframing of official and found documents. You repurpose reports on the MV Tampa, a Norwegian ship that rescued around 450 asylum seekers from their leaking boat in 2001, but there are also more quotidian materials — found quotes, lines from poets and artists, from friends. Your reframing of those official reports (which had already been repurposed by the government as propaganda) brings their violence into sharp relief.

There is an instability in the first-person pronouns of No Document brought about by the fact that I chose to leave its many textual appropriations unmarked — unmarked in the sense that I didn’t include any formal citations of my sources. Sometimes, though not always, these appropriations are “marked” in a graphic sense on the page by my use of strikethroughs, erasures, and italics. Some readers, I think particularly Australian readers of a certain age, might be able to recognize and “place” some of the statements that I appropriate in No Document from government figures, government documents, and contemporaneous media reports.

When I first became involved in activism around Australian border policy and the nation’s treatment of refugees during the early 2000s, I quickly became dissatisfied, disquieted, by a rhetorical strategy prominent in some of that organizing, which says that “we” don’t want these things — offshore detention centers, temporary visas, all the gratuitous racist cruelty — done in “our” name. I don’t find “not in my name” to be a morally adequate response to the question of who is afforded or denied the status of citizenship, even of personhood.

Australian citizenship and nationhood — all national identity — is by definition established in the name of some against others, and if my “name” as citizen is, must be, constituted by the existence of the national border and all that is done to establish and maintain that border, then it was extremely important to me not to establish another division in the composition of No Document, another “we” and “them,” by distancing myself in a grammatical or tonal sense from statements, or from voices, that “I,” in myself, vehemently object to. In a real sense, “I” am also those voices; I am constituted as an Australian citizen by those laws, those political speeches, those media reports. This is not quite the same thing as saying “we are all complicit,” which I also find too easy a rhetorical position.

Drawing out or bringing into focus the constitutive violence of the nation-state in my writing is therefore about bringing attention to what language itself makes possible and permissible for the state to do. I am deeply informed in this approach by M. NourbeSe Philip’s astonishing re/arrangements of legal text in Zong! (2008); by Claudia Rankine’s structural rigor in Don’t Let Me Be Lonely (2004), which, when I first encountered it around 2008, was by far the most “zine-like” poetry book I had ever read, and which therefore had a huge impact on me; and by Alison Whittaker’s use of the page, and the line break, in Blakwork (2018) — a book, not incidentally, that includes a sustained meditation on, and recollection of, the racialized labor force of the abattoir, and the abattoir itself as a space of cuts.

I’m returning to Blanchot’s The Writing of the Disaster (1980) as I assemble these questions. Not least because your work recalls his aphoristic, fragmented style. At one point he cites Valéry: “Optimists write badly.” Then Blanchot adds, “But pessimists do not write.”

Writing this book taught me the truth of Valéry’s statement, I think. In spite of everything, it is a book that holds hope, a book that is on some level about hope, in the Blochian sense: “Thinking means venturing beyond.” For me, optimism is about holding (onto) hope as a state of being that can be brought into being through being (and making and thinking) together. I was on a picket line today of striking University of Sydney staff (of which I am one), in the hours before I sat down to finish this interview: to me that is a state of hope, the practice of hope.

In between answering your questions, I have been listening to David Naimon interview the poet Ross Gay, and Naimon quoted a passage from Gay’s speech in honor of the poet Nikky Finney, in which Gay says:

This is to me a profoundly important point or question: How do we write a rich poetry of witness that does not make brutality the ground? A rich poetry of witness that articulates or responds to or contests or resists brutality, while not granting brutality the status of essential truth.

This is exactly it. History is never determined: it is a series of contingencies, decisions, actions, forces, events. Even or especially in the aftermath of a death, and in the knowledge that the dead have no more time, I want to try and keep the time of history open to examination, to question, to intervention. But we — I — must do this in the knowledge that while the past may be past, it is in a real sense not finished and so cannot be discarded. I’ve been of the radical left since my adolescence, and one of the most tantalizing yet most damaging myths of the radical left is the notion that we can start the world again. It’s a beautiful and terrible idea, and it comes up in various ways over and over in No Document. But there is no starting again, and I think especially not here in Australia, where I write from, on land that has been continuously occupied by First Nations since the beginning of time. A serious and substantive contemporary left must contend with the fact that we cannot break from history, or from Country — from the ways in which we must be, or must become, beholden to the time and law of Country and its true owners, against the nation-state. If the language of the state is partly what makes possible acts of violence done in the name of the state, then part of contesting state power means unwriting, disassembling, that language. History remains for us to (re)make, as does the writing of history, but only in the wake of all that has already taken place.

¤

LARB Contributor

Mireille Juchau is an award-winning novelist and critic. Her third novel, The World Without Us, was published by Bloomsbury in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia and won the Victorian Premiers Literary Award for Fiction. Her essays have been published most recently in LitHub, The Monthly, Sydney Review of Books, Best Australian Essays, and Tablet. Mireille was the 2018 Charles Perkins Centre writer in residence at the University of Sydney.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Feeling Other: On Rajiv Mohabir’s “Antiman: A Hybrid Memoir”

Babi Oloko explores “Antiman: A Hybrid Memoir” by Rajiv Mohabir.

Finding the Story: A Conversation with Lilly Dancyger

Lilly Dancyger discusses her new memoir about her artist father, “Negative Space.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!