Feeling Other: On Rajiv Mohabir’s “Antiman: A Hybrid Memoir”

Babi Oloko explores “Antiman: A Hybrid Memoir” by Rajiv Mohabir.

By Babi OlokoAugust 21, 2021

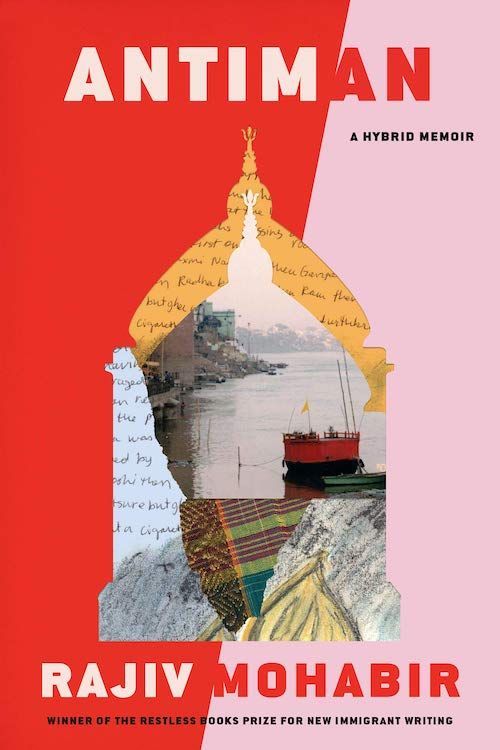

Antiman: A Hybrid Memoir by Rajiv Mohabir. Restless Books. 352 pages.

RAJIV MOHABIR’S ANTIMAN wonderfully lives up to its description as “a hybrid memoir.” As I read poet Mohabir’s debut foray into nonfiction prose, I was reminded of my affinity for collage art — the way that so many different pieces of art can come together in surprising ways to make something beautiful and unexpected has always fascinated me. I found Antiman to be a collage of sorts. Mohabir weaves together stories, prayer lyrics, journal entries, dictionary definitions, and musical chords to create his kaleidoscopic, genre-defying memoir.

Throughout much of Antiman, Mohabir keeps his queerness a secret for fear of being disowned by his family. The titular noun first appears in the text when Mohabir comes out to his cousin Jake:

Jake knew me. I told him over the phone, in my early twenties, that I was into guys.

“Like, sexually?” Jake asked from Queens.

“Yeah, I’ve been with girls too, but I just know I like guys,” I said. I could trust Jake. He knew what it would mean if our family found out.

“There is no word for it in Hindustani, I don’t think,” I remember saying to him.

“Well there is antiman.” Our conversation stalled.

“Antiman,” I repeated. I had heard my aunts and uncles laugh around the table enough to know antiman meant pariah. To be an antiman was to be laughable, it was a secret that could cost me my family if they found out.

Throughout the book, the word “antiman” expands beyond a rebuking of queerness, growing to represent everything that Mohabir feels makes him Other. At its core, Antiman is a tale of searching for belonging, for home. Through his prose written with the enigma of poetry, and poetry written with the movement of prose, Mohabir shares his experiences living life in America as a brown, queer, Indo-Guyanese man — identifiers that make finding a sense of home more than challenging. Mohabir grew up in a Florida town where plastic testicles and Confederate flags hung from the backs of cars. White men in trucks followed him as he drove, calling him “sand n——r.” There, he struggled to belong among his family. He grows desperate to learn about the culture his father all too easily left behind.

When Mohabir finally leaves Florida, a sense of belonging continues to evade him — he travels to India to learn about his family’s past, but the long-lost relatives he hunts down turn out to be strangers, unrelated to him and his family. When Mohabir goes to New York, he finds himself too brown for the queer and academic communities he tries to fit into, where he is overlooked and encouraged to change. Throughout Antiman, Mohabir fields racist microaggressions from Whole Foods customers and homophobia from his traditional family. Undeterred, in true collage-making fashion, Mohabir cuts bits and pieces out of these spaces until he has created something entirely new out of them, an image that has room for him.

One of the most poignantly written relationships described in Antiman is that between Mohabir and his grandmother, his Aji. He sits with her, through the years, eagerly learning as much history from her as he can. A central mission of Mohabir’s is recording as many of his Aji’s songs as possible in order to preserve the language of Guyanese Bhojpuri. His family is simultaneously proud and disdainful of this pastime. Where Mohabir seeks to preserve, his father hopes to forget:

Pap hated himself. Where he was from. The gods that sang him into life. After we came to the United States, he did his best to keep us from knowing our Indianness.

He would rather have silence than Sanskrit; hell than Hindi. […] Our language. Our customs. Even our names. He started going by Glenn instead of his Surjnarine.

Despite Mohabir’s desire to connect with his culture, the insidious grip of internalized oppression comes from him in other ways. He is discontented with himself — too brown, not brown enough, too queer, not queer enough, too Indian, not Indian enough, too American, not American enough. It is difficult to read some of Antiman’s harsher words. “You are nothing,” Mohabir often tells himself. “No one will ever love you. You are fat and hairy.” Antiman is not without moments of levity, however. Mohabir does a wonderful job of balancing sadness and regret with humor and joy. He shares universal moments of happiness — his beloved Aji, first kisses, the feeling that comes with leaving home for big and shiny new cities. As Antiman unfolds, it is wondrous to see Mohabir come into himself in many different ways — as a poet, a lover, a son, a scholar. Slowly but surely, Mohabir transforms. He goes from living for others around him to living for himself.

Antiman’s debut is timely, arriving in the midst of a panicked and confused world in which many do not quite know where they fit in. The quest for the comfort of a home and the joy of belonging is intimately relatable in a time where the very notion of home has been made vulnerable. Mohabir’s experiences are vastly different from my own, yet Antiman is written with a poignant universality that invited me to deeply empathize with him. Though Mohabir’s identity is unique, the pains he describes are intimately familiar to many who feel out of place among their families, American society, or in their very own skin. Anyone who has struggled to belong, forced to put different pieces together to create an imperfect home in which to take refuge, will learn from Mohabir’s enthralling vulnerability in Antiman.

¤

LARB Contributor

Babi Oloko hails from New Jersey and received her BA in history and literature as well as art history from Harvard University in December 2021. She writes art reviews, personal essays, and fiction for various digital publications, and hopes to write a fantasy book centering Black voices.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Immensity of Brevity: On Ben Okri’s “Prayer for the Living”

Babi Oloko is enchanted by "Prayer for the Living," the new collection of short stories by Ben Okri.

Unlearning a White American Dream: On Meredith Talusan’s “Fairest”

Michael Valinsky reviews Meredith Talusan’s memoir, “Fairest,” about growing up trans and albino in the Philippines and the United States.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!