The Cruel Radiance of What Is: On Lindsay Hunter’s “Eat Only When You’re Hungry”

Vincent Scarpa reviews Lindsay Hunter's new novel.

By Vincent ScarpaAugust 8, 2017

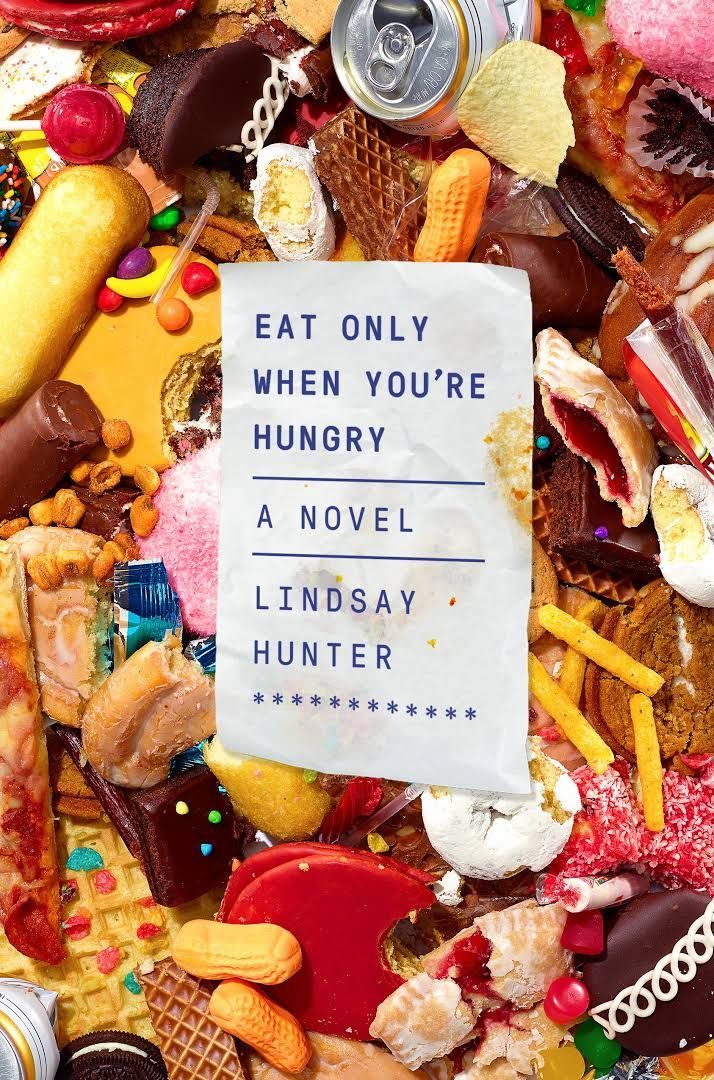

Eat Only When You’re Hungry by Lindsay Hunter. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 224 pages.

AT FIRST, the directive Eat Only When You’re Hungry sounds as if it could have been lifted from a kitschy decorative sign hung in your mother’s dining room. Or else it sounds like the distilled doctrine of an undemanding and likely unsuccessful diet plan. But upon arriving at the last lines of Lindsay Hunter’s latest novel, one appreciates fully the complexity, the fragility, and the sense of strained desire ensconced in an initially straightforward proverb. It’s a fitting encapsulation of Hunter’s great gift: her capacity for occasioning radical realignments in perception; her astonishing ability to unmake a reader’s made-up mind. What some might call the task of fiction. Her previous books — the 2010 debut story collection Daddy’s (Featherproof Books) as well as the collection Don’t Kiss Me and the novel Ugly Girls (both released by Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, in 2013 and 2014, respectively) — evidence a writer of great insight and one with a dynamic, watermarked voice. But it is with Eat Only When You’re Hungry that Hunter arrives at her first masterpiece; a novel of staggering vision and tremendous heart. On full display here are Hunter’s nonpareil technique, her skillful excavation of her characters’ interior landscapes — a digging done both ruthlessly and yet with abundant mercy — and her inspired inventiveness at the level of language.

Everything we need to know about what’s to come in the novel, Hunter delivers in the opening paragraph. We are introduced to our protagonist, Greg, an overweight 58-year-old man whose failings, resignations, and sized-to-scale hopes the novel will come to magnify and appraise. We also learn the novel’s occasion: Greg Junior, or GJ, has not been heard from in three weeks. These three weeks of radio silence from his drug-addicted, peripatetic son appear to be the breaking point of Greg’s prized passivity; the exact amount of time for which he can no longer justify his own stasis. And so he finds himself plunged, ill-preparedly, into consequences he never intended to brave. From his home in West Virginia — where he lives with his second wife, Deb, a woman so levelheaded and polite that she’d “be patting the angel of death on the back when her time came” — Greg rents an RV and prepares to embark on a journey to find GJ. It’s a mark of Hunter’s confidence — as well as a vote of confidence in the reader — that she sets the table so swiftly. She knows that what puts the quarter in the jukebox of the novel and starts it singing is Greg setting out on the highway for his half-baked voyage, armed with only the vaguest of blueprints and an even more imprecise understanding of his intentions.

And so the action of the novel begins. Greg decides to drive toward Florida, where Marie, his ex-wife and GJ’s mother, lives, though calling it a decision is perhaps generous. For can it really be called decisiveness when, presented with no shortage of possible routes to take, one is forever choosing the route with which one is most acquainted? This is one of the many questions Hunter’s novel takes up in a multitude of contexts. As for Greg, what becomes readily apparent is just how defenseless and impercipient he can be when circumstances force him out of the accustomed. Or, as Hunter has it, “When he wasn’t doing what he always did it seemed like all bets were off, anything was possible; he was exposed.” The life he’s built with Deb in West Virginia isn’t one that he sees or experiences as especially happy-making or exciting, but he’s come to embrace its mundanity, to treasure the way it tethers him and decides for him, such that what gets revealed when he finds himself in foreign territory is his staggering ineptitude for being an active participant in his own life, to say nothing of the life of his son. His navigational instincts have fundamentally atrophied, and Hunter captures that degeneration subtly and impeccably.

He tried pushing in but the door wouldn’t give, and he stood dazed in the entryway listening to the muffled music, trying to make out the words […] And then the door opened toward him, revealing a tall man in the ball cap holding two to-go cups of coffee; for a moment Greg wondered if one of them was for him […] He felt foolish about the door, about the whole trip. He always forgot that sometimes it was a pull, not a push.

Though his overall competency has seemingly fallen into stunning desuetude, what hasn’t gone slack with disuse is Greg’s ability to self-scrutinize. His inchoate expedition and the implications of setting about it are mostly inscrutable to him, but over the course of the novel the reader bears witness to an introspection in Greg which belies beautifully our earliest impressions of him.

[Greg] could see how he’d only ever seen GJ as a mirror, not a window. These moments came to him more and more, especially after he retired. These lists of failures. He had time to reflect. What was the point? He could dole apologies out upon GJ one by one, like Band-Aids, like dollar bills. But the damage had been done. Too much road burn. They were both smooth and swollen and beyond themselves […] He was angry at time, how it bent and careened and led you right back to the beginning, how it made strangers of loved ones, how it made family of strangers.

Not exactly the thought process we might expect of someone who, only 20 pages prior, was outwitted by a door, and this is precisely the perceptual realignment of which I wrote earlier, engendered with virtuosity by Hunter over and over again. What’s so thrilling about that passage and others like it — moments wherein Greg finds himself arriving at a level of consciousness which theretofore seemed inaccessible, moments where he begins to comprehend the calibrating effect of long-suppressed experience — is that Hunter’s thumb is never pressed on the scale in their presentation. She has not recruited Greg’s soul-scouring in order to position it across from his present action in that lazy variety of causality employed by lesser writers aiming for a sense of symmetry. Hunter is not interested in symmetry. She’s interested in the actuality of our askewness. She allows her characters to perform complexity and nuance on the very same page that is contextually appraising them — just as we perform our variegated selves in an ever-evaluating world — and this seems to me the most meaningful assignation of dignity possible, delivered from the nexus of aesthetics and ethics.

All of which is to say that Eat Only When You’re Hungry is in every way majestic: stunningly detailed, formidably written, and profoundly affecting. Here is a novel that studies the ways in which we fail and are failed, all the while gnawing at the truism put forth by Joan Didion that “our investments in each other remain too freighted ever to see the other clear.” Here is a novel that asks what it is that tells us that the nature of our appetites are ever within the realm of our own determinate cognition. A novel that destabilizes any ontology which positions one’s obligations and limits as diametrical rather than apposite, or one which insists that to reconcile is necessarily to repair or restore. Mercifully, Hunter is not a moralist. She does not write above the apprehension of her characters, but alongside it. She seeks what they seek. Line by line, page by page, scene by scene, Lindsay Hunter captures more keenly than any of her peers the benumbing monotony and unnerving strangeness of the world in which we find ourselves, lose ourselves, and — if we’re lucky — find ourselves again.

¤

LARB Contributor

Vincent Scarpa is a recent graduate of the MFA program at the Michener Center for Writers. His work has appeared in StoryQuarterly, Indiana Review, Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading, and other journals. He currently lives outside of Atlantic City, New Jersey, where he’s at work on a novel.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“Meld with Me?”: On Alissa Nutting’s “Made for Love”

With "Made for Love," there can be no disputing that Alissa Nutting is funny as hell.

No Answers at All: The Futility of Love in Catherine Lacey’s “The Answers”

Joshua James Amberson reviews Catherine Lacey's "The Answers."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!