The Case for Superman’s Queer and Kinky Underbelly

Superman encourages us to pursue reclamation and defer hopelessness through play, pleasure, and fleeting free moments.

By Meg YoungDecember 11, 2021

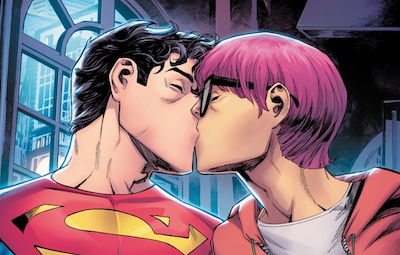

Image courtesy of DC Comics

¤

IN SUPERMAN: Son of Kal-El #5 (written by Tom Taylor and art by John Timms), Jonathan Kent falls for his male friend, Jay Nakamura. For those who don’t follow the convoluted mythology, Jonathan is the son of Clark Kent and Lois Lane. As the acting heir of his father’s title, this means Superman is now canonically bisexual. DC announced Superman’s “coming out” in mid-October, triggering a polarizing reception of celebration and scorn. But these myriad reactions had one thing in common: surprise.

For many, Superman is an idol of white American masculinity in its truest and straightest sense, an emblem of calcified gender dynamics in both his physical invincibility and his consistent rescue of distressed white women such as Lois Lane. The sworn protector of humanity, he most often serves to reflect institutional tastes, critiqued at his best as a capitalist and at his worst as a cop or fascist. It would seem his normativity scales far beyond the hetero variety, making Jon Kent’s bisexuality all the more revolutionary. But is it really?

If, as Sara Ahmed has postulated, to be queer is to stray from a straight social line, then a closer historical look reveals the Man of Steel was queer long before 2021, and even before the turn of the century. What is perhaps most overlooked about Superman and the queerness of his backstory is its profusion of kink — a masked powerhouse of a man in a skintight bodysuit with a penchant for bondage, it’s inevitable that he would become a common source of sexual fantasy. Today, evidence of Superman’s kinkiness is blaring: www.superherofetish.com boasts an extensive library of (predominantly gay) Superman roleplay porn, Superman-themed meetups are beginning to gain traction in fetish spaces, and Cesar Torres’s How to Kill a Superhero tetralogy of queer superhero kink has developed a cult following.

Of course, these tropes are not exclusive to Superman; of any hero, Wonder Woman is most famous for her BDSM overtones, which have been popularly explored through books like Jill Lepore’s The Secret History of Wonder Woman and the feature film Professor Marston & the Wonder Women (2017). Wonder Woman is also a more longstanding member of the canonically queer DC Universe, having had a handful of purposeful queer encounters in past issues of the comics. Most recently, she embarked upon a relationship with fellow hero Zala in Dark Knights of Steel #2, which was released just this week. Meanwhile, Superman’s queerness is considered novel and his kinkiness goes virtually undiscussed in both comics studies and mainstream media. To uncover this forgotten underbelly, we must rewind to a key cataclysm — the birth and death of Superman’s Golden Age.

The Golden Age of comics (roughly from the late 1930s to the 1950s) was sparked by Superman and the subsequent dawn of the superhero. Also characterized by an influx in sexual expression, this period witnessed a peak in Superman’s most kinky and queer aspects. In these early days, Action Comics (the magazine that published Superman) shared newsstands with some very kinky material. Amid a post-Victorian, pre-war boom in sexual and sadomasochist interest, the production of new bondage-rich Westerns and erotica pulp stories became particularly profitable. One especially popular erotica pulp series, Spicy, was even secretly owned by Superman’s publishers. While there is a dearth of evidence to prove fetish was intentionally infused into Superman, it would be equally difficult to argue that co-creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were unaware of the market for kink.

Given Shuster’s later stint as illustrator of the BDSM pulp series Nights of Horror, it can at least be said that he retroactively identified Superman’s erotic potential. Craig Yoe broke the story of the Superman co-creator’s seedier illustrations to the greater public just over a decade ago in Secret Identity: The Fetish Art of Superman's Co-Creator Joe Shuster, noting that while they have no authorial record, the simple lithographic illustration style and iconic character design (i.e., replicas of Clark Kent and Lois Lane) are unmistakably Shuster’s. The cartoons depict heroes saving women from degradation-obsessed madmen whose torture devices recall those of Metropolis’s supervillains. Other story lines show women dominating men — chaining, leashing, knotting, cuffing, and lashing, only for the men to kiss their feet in gratitude. In these pulps, the tropes of Superman were both echoed and subverted.

In 1954, Nights of Horror contributed to the collapse of the Golden Age. That summer, the Brooklyn Thrill Killers went on a murder and torture spree and a popular face of the anti-comics movement, psychologist Dr. Fredric Wertham, conducted their trial screenings. During the screenings, Wertham prompted the ringleader, Jack Koslow, to name Nights of Horror as an inspiration for his crimes. By that time, the anti-comics movement had been gaining steam for over a decade and was approaching a tipping point; Koslow’s was the perfect story to confirm comics as the great bellwether of juvenile delinquency, and Wertham used it to advance existing moral panic toward a fever pitch. Later that year, the Comics Code Authority (CCA) was established, prohibiting among other things political dissent, lust, sadism, and masochism in comics.

At its most dramatic, Nights of Horror was the last flare of a self-destructing explosive. Shuster’s initial illustrations in Superman, conceived within a market ripe for kink, evolved into erotica decades later, and then into a monstrous public enemy. The issues of Superman that followed, cautiously adhering to the guidelines of the CCA, were largely sanitized of excessive bondage and depictions of sadistic violence. It was in this way that Superman’s kinkiest — and queerest — moments became sealed within the Golden Age, over 70 years before present day.

¤

The interweaving of kink and queerness was crucial to the crusade against comics. In Wertham’s infamous anti-comics manifesto, Seduction of the Innocent, he cites the confession of a young gay psychotherapy patient. “I was put in the position of the rescued rather than the rescuer,” he says, “I felt I’d like to be loved by someone like Batman or Superman.” While Wertham’s work is largely factitious — in 2013, Carol L. Tilley substantiated that he fabricated interviews with young subjects — this and other accounts from Seduction were key in electrifying the drive against comics that would later lead to the development of the CCA. For Wertham and other preachers of moral panic, queerness and kink made a perfectly terrifying pair of sexual degeneracy.

However, just as these two communities jointly bore the brunt of social exile (and in Superman’s case, scapegoating), their movements crossed over into one, often serving to resist the sentiments wielded against them. Patrick Califia, an early advocate for the normalization of lesbian BDSM, is a notable member of one such movement. In his book Sapphistry: The Book of Lesbian Sexuality, he lays foundations for the study of BDSM as an authentic sexual practice. Califia writes that bondage, forced sex, authoritative partnership, and even hypnosis can be interpreted “as metaphors for abandoning ourselves to sexual pleasure.” In resisting condemnation of masochist desire, this notion also subverts Wertham’s victimization of his alleged patient. Under Califia’s logic, the patient’s inclination to submit to Superman is not a sign of delinquency, but is instead an organic and reasonable reaction.

Califia’s notion also reminds us that imagery and media need not be explicitly about sex to be sexual, nor explicitly about kink or queerness to be kinky or queer. It’s worth noting that Nights of Horror never depicts actual sex being had — the bondage and torture on display stand alone as acts of violence, used by most readers (with the exclusion of the Brooklyn Thrill Killers) as a map along which sexual fantasies can be conceptually navigated and played out in a safe and private manner. Superman depicts these acts in a more parodied and playful way than Shuster’s erotica pulps, but that far from discounts the merit of its capacity for sexual fantasy; if anything, it serves to expand upon the erotic metaphors Califia describes.

In their psychological inquiry, Superhero Comics as Moral Pornography, David A. Pizarro and Roy Baumeister argue that “superhero comics offer the appeal of an exaggerated and caricatured morality” in the same way pornography offers “the appeal of the exaggerated, caricatured sexuality.” Within Superman’s parodic depictions of power, Califia’s erotic metaphors find common ground with Pizarro and Baumeister’s moral pornography. For one, Superman’s role as a caricature of enforced morality represents its own collection of erotic metaphors through his exacting of punishment and mercy upon civilians. At the same time, the superheroic playfulness that enables his enforcement to become caricatured is what makes these metaphors especially voyeuristic. It is in this way that the potential of voyeurism in Superman surpasses the respective satisfactions of enforcing a moral code or abandoning oneself to pleasure. The synthesis of these two phenomena is what makes the inherent kinkiness of Superman shine, and it is also what makes it so inventive.

Much of Superman’s focus on caricatured discipline can be owed to the cultural influences under which Shuster and Siegel grew up. In youth, they were inculcated with sideshow posters touting the impossible brawn of strongmen and the peculiar quirks of human “oddities.” Each reduced to a single abnormality, performers were made into caricatures of themselves in advertisements and shows alike. The image of the strongman stood out as the prototype of a dominant hero, no doubt mirrored in Superman’s herculean form, and human “oddities” became inspirations for the powers of future characters. More importantly, however, the suffering required from sideshow performers became glorified; the intrigue of audiences derived not from “oddities” alone, but also from the tolerance of emotional and physical pain necessitated by their performances. For Siegel and Shuster’s generation, voyeurism adopted a connotation of punishment and with it, a center stage.

The Superman comics of the Golden Age make no mystery of this fascination. Their moral and erotic voyeurism hinges tightly on punishment as Superman often enacts the fantasies of an ultimate dom: tying people up with rope, slamming them against walls, chucking them off the horizon to certain death, and locking them behind bars. He does not just assert his dominance as a mere law enforcer; he dominates as a supernatural force. His definitions of justice drive him to dominate Metropolis at his every whim, and until the first supervillain shows up in issue 13 of Action Comics, every civilian submits to him, whether as a willing rescuee or a surrendered deviant. Once the first supervillain, the Ultra-Humanite, is revealed, his and Superman’s back and forth is all the more kinky, a mutual enjoyment in playing with dramatic domination and submission that continues for issues to come. In the Golden Age, the erotic metaphors of immediate dominance and pure power struggle were prioritized above all else. The softer, complementary moments that characterize the Superman stories of today were scarce, deferred as distractions from the main event.

The achievement of this “main event” can in part be owed to another of Siegel and Shuster’s generational markers: a budding national interest in the power of the alter ego. When Siegel and Shuster turned five, Zorro debuted in All-Story Weekly, inspired by John Rollin Ridge’s The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta. One year later, Douglas Fairbanks Sr. sported Zorro’s iconic black mask and cape in the comic’s first film adaptation. Zorro was a key departure from the protagonists of Thomas Dixon Jr.’s novel The Clansman (later adapted into The Birth of a Nation), whom Chris Gavaler notes are the first “heroes” in 20th-century American literature to adopt dual identity through costume. The dark sail of his disguise subverted the Klan’s in both color and impetus. Instead of fighting in the name of white power, Zorro sought vengeance for the helpless and aid for the oppressed, among whom were indigenous people and women. He set a precedent for alter egos that empowered heroes to rescue those in need, marking him as the first hero to bear dual identity in the name of tolerance.

Decades later, when Superman was finally born, he inherited both Zorro’s justice-seeking dual identity and his mask-cape ensemble. However, the costume was now a skintight suit — technicolor, latex-like, and an abrupt departure from the formless cloaks of his predecessors. While latex fetishwear would not become a staple in the BDSM community until the 1960s, latex clothing has been documented as an erotic fixation as early as the 1920s and the material itself had been around for nearly half a century by the time of Superman’s launch. His costume is kinky in today’s terms, but even then it carried implications of fetish.

As the world’s first superhero and an alien to Earth, Superman’s otherworldly constitution evolved the essence of heroic roleplay. His transformation from Clark Kent to Superman was not a performance in the same way it was for his forerunners; unlike them, his heroic disguise was the only way he could publicly reach his full genetic potential. In more recent adaptations of the comic including Kal-El and Man of Steel, more emphasis is placed on the internal struggles and emotional depth of Superman’s life as a “human,” suggesting the real him is the man behind the mask. But during the Golden Age, the mask made the man.

This is why Superman’s disguise is so important. In order to embody his truest self without ridicule, he had to don a sexually charged uniform and leave behind the persona he presented to co-workers and friends. He ripped through his layman’s clothes to expose not an exaggerated version of himself, but instead his most authentic presentation: playful, raunchy, and distinctly unprofessional. Put plainly, Not Safe For Work. And, much like those with their own persistent kinks, Superman’s self-actualized identity hinged on this erotic roleplay. His adoption of a hero’s persona by intrinsic necessity, rather than choice, is an acutely queer act in a few ways. It is deeply kinky, but it also serves as an uncanny allegory for the closet, a parallel that author Joseph Brennan aptly calls “the supercloset.”

¤

As a true American microcosm, Superman has always enforced the military’s most propagated agendas: he brawled with Nazis and led fundraising for national defense in the 1940s, defended the world against alien terrorists after 9/11, and his most recent on-screen appearances have received funding from the National Guard. The “justice” he serves is deeply indoctrinated by the state, his adventures reiterating capitalist nationalism with minimal subtlety.

However, the conversation between Superman and capitalism often contradicts itself. While Superman’s powers would allow him to live off robbing the wealthy without consequence, for instance, he chooses to work and encourages civilians to do the same. Simultaneously, he is restrained by his own life as a worker, able to self-actualize only when he tears the seams of his suit and tie and discards his glasses. Superman propagates a capitalist agenda, but even he is exhausted by serving the machine; when he leaves his day job and passive workplace mindset, he seeks to reclaim a sense of control through domination, roleplay, and physical release.

This contradiction reveals clear holes in Superman’s role as a mirror of institutional power, but the real subversion of this mirroring occurs when channeled through real-life kink. After all, BDSM is bidirectional — doms and subs often take equal part in deciding what happens, the sub at times more demanding than the dom in what they want done to them. At the very least, all parties are free to set their own boundaries, likes, and dislikes. That’s certainly more control than the citizens of Metropolis have over the rules of their everyday world, and far more than any of us have over ours.

The notion of BDSM as a mode of control over power structures is nothing new. In Sex, Power, and The Politics of Identity, Foucault makes the key distinction between power as “a strategic relation which has been stabilized through institutions,” and BDSM as, “an acting-out of power structures by a strategic game that is able to give sexual pleasure or bodily pleasure.” When we turn to the Golden Age of Superman, we find that kink implies a similar kind of subversion. Kinky consumers of Superman may “act out” submission under their own terms just as they may dominate in place of their oppressors.

In acting this out, the world of Superman does much of the theatrical work for us. Izar Lunaček writes in Juicily Juxtaposed: Pleasure Tropes in the History of Erotic Comics that the artifice of comics “allows the staging of the most bizarre […] sexual scenarios without the laws of physics or discomfort or concrete actors getting in the way.” In this way, the simple yet limitless fantasy of Superman supplies a super-powered path beyond the mere reclamation of capitalist submission. Through Superman (and every consequent superhero who emulates him), readers have the opportunity to vicariously explore impossible and astonishing power dynamics in their own sex lives. And what’s more, they can use these fantastical allegories to reclaim a primal sense of control within a system which repeatedly denies it.

Of course, this is no perfect reclamation. Just as Jeremy O. Harris’s Slave Play leaves us questioning the merit of antebellum kinks in interracial American relationships, Superman’s Golden Age tendency to feature characters of color in near-exclusively villainous roles — ever the subjects of preternatural policing — complicates how successfully this fantasy can play out as a mode of true reclamation. But both of these works have one crucial thing in common: they neither condemn nor condone these acts, instead suggesting that the question of how sex and kink interact with institutional power can never be answered in definitive terms. Kinkifying subjugation will always come with its caveats, and not everyone will find reclamation in BDSM; many are likely to find just the opposite. But the potential remains for others to discover a deep and unique catharsis, and it is through these varied and often polarized reactions that the true complexity of the relationship between kink and capitalism is revealed. In the shortcomings of Superman’s subversion, the question of this relationship is not nulled, but deepened.

It is for this reason that while Jon Kent’s coming out in Son of Kal-El is a great step forward, the potential of kink to subvert the comic’s nationalism and provide a temporary reprieve from capitalist despondency offers a very different, more extraordinary kind of promise. After all, if to be queer is to stray from a straight line, Superman’s midcentury emulsion of kink and capitalism is far more queer than today’s addendum of bisexual super-progeny. Even within the illustrations of Son of Kal-El, little room is left for the hyperbolized voyeurism of the Golden Age. The air of artifice grooved within Shuster’s simple figures is lost in its more realist style, at times veering straight into the uncanny valley. Superman mostly retains the kinkiness of his roleplay and his knack for enforcement, but forfeits the quotation marks of camp that characterize the potent fantasy of the original comics.

In the age of rainbow capitalism, LGBTQ+ representation remains invaluable for queer youth, but it is also a commercial strategy. Amid a media market saturated with safe queer prototypes of cisgender gay and bisexual white boys, a bisexual Superman strays just beyond the straight line of social acceptance, but not far enough to cross a new boundary. To ask why Jon Kent is queer is also to ask, why now? In many ways, Son of Kal-El is but an ordinary perseverance of the profitable American microcosm that Superman has always been.

The most radical effects of Superman are felt when we recognize what is hidden in plain sight. From his conception, he was kinky, super-erotic, and very queer. As both a character and a world, Superman is a most unique expression of Americana, a masterpiece of camp fetish at its best and a violent propaganda scheme at its worst. Its capacity for erotic redemption is a sort of immersion therapy, inviting us to bask in a bright caricature of the structures we despise. As the world’s first superhero, Superman signifies the start of an ongoing lineage of power play, one that encourages us to pursue reclamation and defer hopelessness through pleasure and fleeting free moments. This — not bisexuality — is the most revolutionary thing about it.

¤

Meg Young is a writer based in New York and a student of English at Barnard College.

LARB Contributor

Meg Young is a writer based in New York. They study English at Barnard College, where they serve as an editor for the Columbia Journal of Literary Criticism and event coordinator for Echoes Literary Magazine.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The De-Colonization of Miles Morales

Vincent Haddad on the promise of Miles Morales.

Dr. Manhattan is a Cop: "Watchmen" and Frantz Fanon

Aaron Bady, for Dear Television, considers the way that HBO's Watchmen came so close to unmasking the world's real supervillain.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!