The Book of Saint Phalles

Jackson Davidow ponders "What Is Now Known Was Once Only Imagined," Nicole Rudick's look at the art of Niki de Saint Phalle.

By Jackson DavidowApril 25, 2022

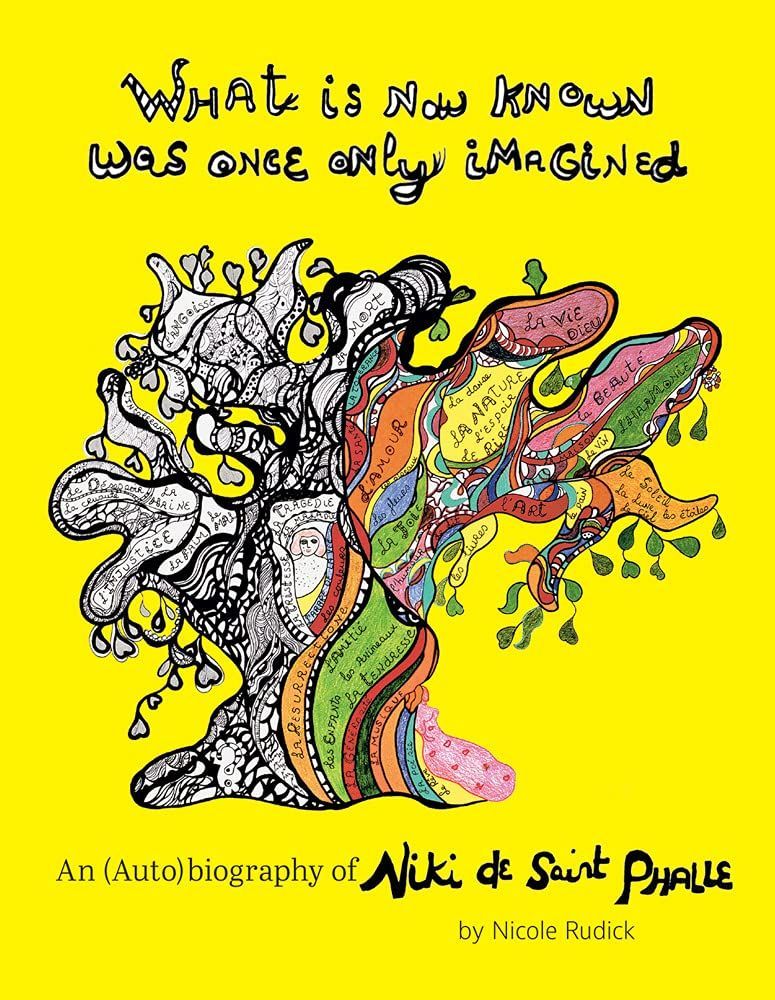

What Is Now Known Was Once Only Imagined: An (Auto)biography of Niki de Saint Phalle by Nicole Rudick. Siglio. 267 pages.

“DOES ONE HAVE to go through catastrophe to arrive at vision?” asked artist Niki de Saint Phalle in the pages of her diary on November 5, 1995. “I think that each person who has a unique vision,” she continued, answering her own question, “does go through a very close encounter with Death, either through himself or the shock of sudden death in others. Or insanity.” For Saint Phalle, disease, loss, neglect, madness, and trauma, when embraced and repurposed as raw material for art, had the potential to become rich, generative, and even healing.

Yet it was not solely the catastrophic that fueled her spectacular body of work, which spanned sculpture, architecture, painting, film, performance, design, and literature from the early 1950s until her death in 2002. See, for example, Saint Phalle’s 1987 lithograph, L’Arbre de la vie, in which she reinterprets the biblical image, the bark’s twists and crevices forming a whimsical mind map divided in two. On the tree’s left side, the artist lodges French words conveying negative feelings and phenomena in the black-and-white patterned branches: anxiety, death, tragedy, sickness, hunger, injustice, hopelessness, cruelty, sadness, intolerance, nothingness, “le mal.” The right side, meanwhile, is like the Technicolor world of Oz, bursting with brilliant hues and an assortment of upbeat nouns: friendship, tenderness, books, art, wine, harmony, the sun, joy, flowers, love, health, laughter. Imagining the tree of life within a quirky cosmology of yin and yang, Saint Phalle joins its two halves with the insertion of a woman’s head, which peeks out, owl-like, from a cavity in the trunk. Perhaps a portrayal of the artist herself, the figure is rendered with subdued color, as if brokering these two affective registers that, entangled like the roots of a tree, together make her art possible.

This felicitous image adorns the cover of Nicole Rudick’s What Is Now Known Was Once Only Imagined: An (Auto)biography of Niki de Saint Phalle. Far from an ordinary biographical study of Saint Phalle, What Is Now Known Was Once Only Imagined is, as its evasive title (borrowed from the artist’s 1979 print of the same name) suggests, a wide-ranging exploration of her life as she experienced and articulated it across a miscellany of lyrical texts and pulsating images. Tracking Saint Phalle’s creative, personal, and professional odyssey from childhood to old age, with an emphasis on persistent themes of feminism, abuse, and illness, the book is just as much a testament to the willful production of artistic subjectivity as it is to the manifold powers of art as an instrument of therapy, education, and activism. For the artist, the necessity of using art and writing to construct a self — or, rather, a plurality of selves — was inseparable from the drive to envision the world anew.

¤

As is the case with several other iconic 20th-century women artists, Saint Phalle’s life story is ripe for unbridled mythologization. It’s a wonder, frankly, that there isn’t a bad biopic yet. Born to an American mother and a French father in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, in 1930, Saint Phalle grew up in New York City in a moneyed and repressive Catholic household. Her mother was physically and emotionally violent, and her father abused her sexually starting at the age of 11. To survive and resist her family’s cruelty, she gravitated toward the arts.

After Saint Phalle fell in love with and married like-minded Harry Mathews in 1949, the young couple had a baby and moved to France. There her mental health increasingly unraveled in the early 1950s, due in no small part to a new awareness of her father’s horrifying conduct, a trauma heretofore buried deep in her unconscious. In her telling, “My psychic pain was like a giant rat trap. It was much worse than depression. There was a horrible feeling in my chest that I was unable to get rid of, coupled with an inner scream that would not stop.” During a six-week stay at a psychiatric clinic, Saint Phalle turned to painting as an essential vehicle for therapy and empowerment. As she recalled, “I could explore the magical and the mystical which kept the chaos from possessing me. Painting put my soul-stirring chaos at ease and provided an organic structure to my life, which I was ultimately in control of.”

Being a wife, mother, and homemaker was frequently incompatible with her growing commitment to making art and establishing a career as an artist. Eventually, Mathews and Saint Phalle ended their relationship in 1961, and the children went to live with their father. Despite, or likely because of, her lack of formal artistic training, Saint Phalle cultivated a free-spirited aesthetic that was informed by her disparate encounters with cultural works and practitioners on both sides of the Atlantic. Kinetic artist Jean Tinguely became her collaborator, friend, and lover for many years. In the early 1960s, she rose to prominence with her Tirs series, which epitomized several emerging conceptual and formal trends in contemporary art: intricate assemblages with dart boards (a nod to her friend Jasper Johns’s famous targets) that sometimes reached a state of completion during “happening” events when she and other participants fired guns at the works, causing bags of bright paint to explode upon them.

In the same period, she created colossal mixed-media sculptures of voluptuous women called “Nanas” — modern-day Venus of Willendorfs. The most legendary one was HON, developed in collaboration with Tinguely and Per Olof Ultvedt at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 1966. This Nana took the form of a massive recumbent pregnant woman with a vaginal opening through which visitors entered to find inside a wonderland containing a milk bar, cinema, and fishpond. With its impressive size and visionary framework, HON paved the way for the large-scale site-specific sculptural works for which Saint Phalle is perhaps best known, particularly her magnum opus, the Tarot Garden in Tuscany. From 1974 to 1998, she labored over and funded this elaborate sculpture park that conjured up a world inspired by Tarot cards. Other significant undertakings included a wildly popular perfume line, launched in 1982, and a series of AIDS awareness and fundraising projects, beginning with her 1986 book, AIDS: You Can’t Catch It Holding Hands.

Saint Phalle remains an elusive figure in the history of art. It seems nearly impossible to discuss her without falling into a cringey mode of psycho-biographizing that overstates, and further mythologizes, the numerous social and psychological tensions that inevitably shaped her life and career: having conflicting French and American national identities; bridging the late modernists and the postmodernists; participating in a male-dominated avant-garde yet achieving fame for a self-taught, self-proclaimed feminine aesthetic; eschewing alignment with the women’s movement but, in many ways, leading a resolutely feminist life; fashioning an effervescent public persona while creating acutely intimate work that, though often joyful, could be scary in its piercing intensity; surviving trauma, depression, and a concatenation of miserable physical ailments by making art — but being prone to certain diseases because of her constant exposure, occasioned by her artmaking, to dangerous fumes, fibers, and chemicals.

As the artist herself once remarked, “One of the reasons very little has been written on my work is that I am difficult to categorize.” This is also one of Rudick’s refrains, and though, yes, Saint Phalle continues to be relatively underrepresented in existing histories of postwar art and visual culture, public interest in her unorthodox oeuvre has been on the rise. What Is Now Known Was Once Only Imagined comes on the heels of two major exhibitions devoted to the artist last year. On view at MoMA PS1, Niki de Saint Phalle: Structures for Life focused on the artist’s sculptural works and long-standing interest in spatial politics. Highlighting the Nanas and Tirs assemblages, a second retrospective, Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s, meanwhile, took place at the Menil Collection, and will soon travel to the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. Along with these worthy curatorial efforts, Rudick’s book is an attempt to grapple with Saint Phalle’s enormous cultural legacy 20 years after her death.

¤

What Is Now Known Was Once Only Imagined is not, let me make clear, a biography or an autobiography — at least in any conventional sense. Instead, it is a chaotic collage of Saint Phalle’s writings and artworks, both finished and unfinished, most of which are now preserved in her archive at the Niki Charitable Art Foundation in Santee, California, and have not previously seen the light of day. As far as I can make out, the texts mainly derive from her published memoirs, autobiographical essays, and written correspondence. The titled artworks, however, are helpfully cataloged in the back of the book. With the integration of these materials, readers gain rare insights into the visuality of her writing as well as the textuality of her art. Saint Phalle’s penmanship, ubiquitous across her works, is unmistakably midcentury French with its flouncy swirls and plump loops and contributes to the vibrant feminine sensibility of her storytelling.

Except for Rudick’s essays that bookend What Is Now Known Was Once Only Imagined — a theory-driven foreword and a more historically anchored afterword — there is a lack of discernible structure, no chapters, inconsistent pagination, minimal references. A feverish velocity characterizes the book. As Saint Phalle herself observed, “It seems as though I am always in movement, always in some new research, sometimes moving too fast and not developing certain periods long enough.” The same criticism could be leveled against Rudick’s book. Flipping through the pages, I often have no idea what I am looking at — a bewildering sensation for an overwrought art historian, craving a basic sense of context and chronology. Even so, the quality of unknowingness is what makes the work pleasurable and addictively readable. I know of no other book like it.

This provocation is arguably the whole point. Rudick has liberated not only herself, but also her beloved Saint Phalle, from (auto)biographical norms and, in so doing, has dreamed up a new genre of critical writing at the crossroads of art, literature, and history. Perusing the book is like doing archival work with an unreliable finding aid — without, of course, schlepping to the archive. Intentionally yet intuitively arranged, Saint Phalle’s works “make meaning,” according to Rudick, “through their contiguity, their role in a syntactic construction (each work a word in a sentence, a sentence in a paragraph, and so on).” As such, I am inclined to situate Rudick’s authorial act in a genealogy of contemporary artists critically engaging with archives. A few examples of this include Renée Green restaging Diedrich Diederichsen’s belongings in Import/Export Funk Office (1992–’93); Danh Vo arranging a selection of Martin Wong’s personal collection in I M U U R 2 (2013); Sadie Barnette mining familial and bureaucratic histories in Dear 1968,… (2016–’18); and Dell Marie Hamilton developing an installation of an inherited archive in The End of Susan, The End of Everything (2021). Across these artworks, museum audiences are left to extract meaning from the reorganized objects’ textures, patterns, and juxtapositions. What Is Now Known Was Once Only Imagined does something similar in book form.

Rudick asserts that her book is “an act of cooperation or participation between Saint Phalle and me, and the reader, too,” which is why she deems it an “(auto)biography.” While writers have long transgressed and innovated the literary genre of biography, from Gertrude Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933) to McKenzie Wark’s Philosophy for Spiders: On the Low Theory of Kathy Acker (2021), Rudick’s coinage of this hazy term usefully underscores her complete identification with, and affection for, Saint Phalle (with whom, we are reminded, she shares a first name). The participatory nature of the artist’s singular practice seems to call for an experimental form of life writing, even if she died two decades ago and never gave Rudick her explicit consent to collaborate. And yet, in a way, isn’t every editorial, curatorial, and historiographical operation “an act of cooperation or participation” between the work’s subjects, its authors, and its readers? Foregrounding Saint Phalle’s voice as a mythologizing agent in her own story, this book raises broader questions about the making and remaking of artistic subjectivity as a complex negotiation.

¤

LARB Contributor

Jackson Davidow is an art historian and a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for the Humanities at Tufts University. His cultural criticism has appeared in Art in America, The Baffler, Boston Review, and elsewhere. He is writing a book about global AIDS cultural activism.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Pulse on the Eye: The Art of Helen Frankenthaler

A sparkling new biography of a major female abstract expressionist painter.

Art Matters Now — 12 Writers on 20 Years of Art: Johanna Fateman on the Founding of Creative Capital

In collaboration with Creative Capital, LARB will publish 12 essays over 12 months on issues facing contemporary art in the United States.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!