Testimonies of Influence: On Imani Perry’s “South to America”

Suzanne Van Atten discusses the scope and complexity of Imani Perry’s explorations of race and the South.

By Suzanne Van AttenJanuary 25, 2022

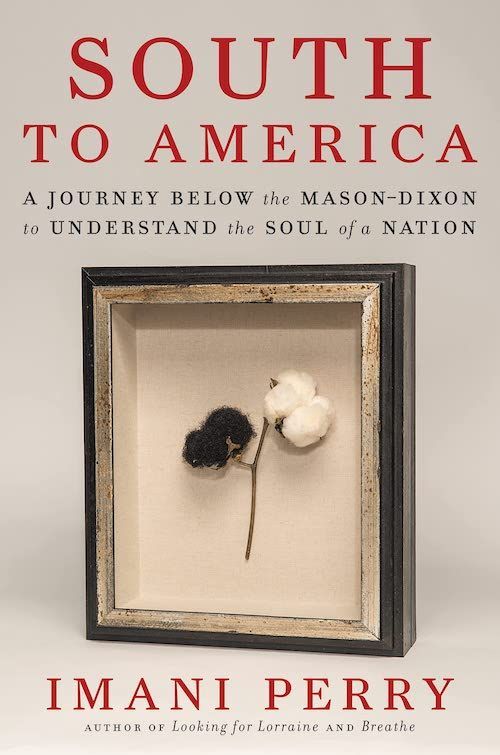

South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation by Imani Perry. Ecco. 432 pages.

THE AMERICAN SOUTH is a place that is sometimes romanticized and oftentimes maligned, especially by those who live north of the Mason-Dixon line or west of Texas. Popular culture will tell you Southerners are fat, poor, and uneducated. Statistics will tell you they are politically conservative and reactionary. History will tell you they are racist and violent. While there is some truth to those assessments, they don’t come close to painting an accurate picture of the whole truth, which is much more complex, multifaceted, and contradictory.

In her provocative new essay collection, South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation, Imani Perry contends that the South has had a tremendous impact on the history of our nation and that it continues to exert significant influence today.

In the inestimable words of OutKast’s André 3000, as he threw down the gauntlet between East Coast and West Coast rappers at the 1995 Source Awards, “The South got something to say.” Perry, a professor of African American studies at Princeton and winner of a PEN Award for her biography of playwright Lorraine Hansberry, accepts the challenge of speaking for the region. And in the process, she throws down her own gauntlet, presenting her essays as a cautionary tale for what the future may hold if we don’t pay heed:

The consequence of truncating the South and relegating it to the backwards corner is a misapprehension of its power in American history. Paying attention to the South — its past, its dance, its present, its threatening future, and most of all how it moves the rest of the country about — allows us to understand much more about our nation …

Born in Birmingham, Alabama, Perry grew up in Massachusetts and Chicago, and currently lives near Philadelphia. That distance from the region has given her a unique perspective as she ventures back to her roots and views it anew. Each chapter examines a single location — mostly cities, but also states and subregions. In each one, Perry scrutinizes the destination, and plucks threads from its history, its culture, its personality; then she weaves them together to tell a story about the place that reflects, informs, or portends our national psyche. The result is a compelling, thought-provoking read sure to spark both consensus and debate, but ultimately it serves to illustrate just how much race impacts life in this country.

The book starts in Appalachia, the remote mountainous region that spans from Mississippi to New York, and touches 10 Southern states. For “Errand into Wilderness,” Perry visits Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, where white abolitionist John Brown attempted a slave revolt in 1859 and paid for it with his life. There she strikes up a conversation with a Confederate reenactor, which leaves her feeling conflicted. “As skeptical as I was of why anyone would want to playact at preserving slavery, I was endeared to him. He was friendly,” she writes. “I decided to maintain the easy tenor of our conversation out of curiosity but also in an effort to create and keep the peace. I was vaguely ashamed of that.”

She considers the stereotypes of mountain people — the “mocking taunts about inbred cousins, feuds and rednecks” versus the “admiration for Appalachia’s folk heroes.” As an example of real-life heroes, she holds up the region’s coal miners as “poor folks who usually stayed poor no matter how hard they worked,” but who played important roles in the industrialization of the country, as well as the history of labor unions.

As bad as working conditions were for white coal miners, they were worse for Black miners. Yet, their shared misery wasn’t enough to bridge the racial divide, Perry observes.

Poor and working-class White Americans were taught that if they expressed solidarity with Black people, also exploited, also laboring hard, they’d lose what [W. E. B.] Du Bois termed “the wages of whiteness,” those benefits that went along with not being at the bottom of the social hierarchy.

Out of Appalachia’s labor union movement came the Highlander Folk School, started during the Great Depression in Monteagle, Tennessee, to train labor organizers. In the ’50s, it turned its attention to civil rights and desegregation, attracting activists Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. Today it’s called the Highlander Research and Education Center, and its focus is the environment, worker safety, and immigrant rights.

“Highlander belies the mythology of Appalachia,” writes Perry. “But it also fits directly in the history of organized labor and a history of imagining, in particular imagining a different way of being in the world, together.”

Perry’s essay on Atlanta, “King of the South,” is a bold takedown of a city often held up as a shining example of a “Black mecca” because of its large Black middle class and its Black political structure. But Perry calls it “a spectacle of American consumption and ambition,” where, despite a population that is more than 50 percent Black and the presence of considerable Black wealth, Black homeownership is low, boardrooms remain white, and “a very old social order grown up from plantation economies into global corporations still leaves most Black Atlantans vulnerable.”

She ponders “the allure of Black prosperity in Atlanta. Especially for its most successful agents. A quiet reconciliation, I suppose, that their possession of so much rests up on the bulk of their folks having so very little, even within the city walls. And a louder proclamation of the glory of not being boxed into the constraints of racism.”

Perry’s tone turns to sugar in “Home of the Flying Africans,” a lyrical essay about the Low Country, the coastal areas of South Carolina and Georgia where slave ships docked after their long journeys from Africa and the Caribbean.

She starts on a nostalgic note, recalling the traditional Gullah Geechee clap games and folk songs she learned as a child from Bessie Jones, a member of the Georgia Sea Island Singers. The ensemble was established in the early 1900s by descendants of enslaved people. First documented in 1935 by famed Smithsonian Institution archivist Alan Lomax, the ensemble continues to tour and perform today. “To this day, the children of the children of the children of the slave South, in ghettoes and hoods across the country, will clap and stomp in unison,” she writes.

Clearly smitten with the historic town reportedly spared from General Sherman’s torch because it was so beautiful, Perry ventures to Savannah to visit Dr. Walter O. Evans, who, along with his wife Linda Evans, owns a stunning collection of American Black art. An art collector herself, Perry discusses with Evans the dissolution of the tight communities and salons that used to rally around Black artists. In short, Evans tells her, “Black artists don’t need Black patrons in the way they once did” because their work has become so valuable. But Perry says there’s more to it than that.

One of the difficult side effects of desegregation — and you’ll hear it again and again from Black people who lived in the before time — is that something precious escaped through society’s opened doors. Even acknowledging how important desegregation was, the persistence of American racism alongside the loss of the tight-knit Black world does make one wonder. What if we had held onto those tight networks ever more closely, rather than seeking our fortune in the larger White world that wouldn’t ever fully welcome us beyond one or two at a time?

While in Savannah, Perry walks past the childhood home of Flannery O’Connor, an author Perry admired for exposing “some of the vulgar innards” of the South. Nevertheless, when The New Yorker wrote a piece on O’Connor’s bigotry in 2020, Perry was glad to see the author called out,

but also I felt that familiar disappointment that a writer who I not only liked, but who I believe understood and explained Southern idiosyncrasy and violence so well had been such an utter failure when it comes to what might be the most basic moral question in the history of this country: Can it ever be remade in the image of the Declaration of Independence? Or will the founders’ sins haunt us always?

The essay ends at the historic Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina. Founded in the early 19th century, the church was the site of a mass shooting in 2015. But that was not the first time the church had been under assault. When Denmark Vesey, a freed slave and member of Mother Emanuel, was accused in 1822 of plotting a slave revolt during church sermons, he was executed by hanging and the sanctuary was burned to the ground.

“The point is that there were, of course, cycles of representation and cycles of resistance,” writes Perry.

I suppose the thing I most want to say is that it is rarely acknowledged that every time that group of parishioners gathered in Mother Emanuel, they stood in a tradition of refusing to be rendered soulless and unfree. No gentrifiers, no hierarchies, no displacement, no new arrivals, and no, not even massacres that laid bodies low, one on top of another, can erase that. Their testimony is already embedded in the land.

¤

LARB Contributor

Suzanne Van Atten is an award-winning book critic and travel writer based in Los Angeles. She has been published by Rolling Stone, The Guardian, WebMD, Los Angeles Magazine, and The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, among other outlets.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Building Trust: On Mashama Bailey and John O. Morisano’s “Black, White, and The Grey”

A joint memoir about the development of a restaurant in the Deep South.

Ghost Stories: On J. Nicole Jones’s “Low Country”

Suzanne Van Atten review J. Nicole Jones’s debut book, a memoir of her experience growing up in the South.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!