Building Trust: On Mashama Bailey and John O. Morisano’s “Black, White, and The Grey”

A joint memoir about the development of a restaurant in the Deep South.

By Amy BowersOctober 29, 2021

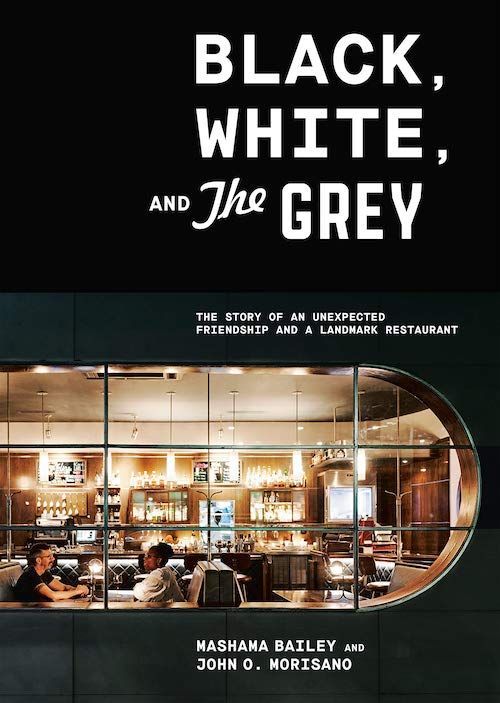

Black, White, and The Grey: The Story of an Unexpected Friendship and a Beloved Restaurant by Mashama Bailey and John O. Morisano. Lorena Jones Books. 304 pages.

ON MY FIRST DAY of school in Central Florida, my lunch tray was filled with foods I did not recognize. I took the tray from the lunch line and walked slowly to my seat, feeling mildly disgusted by what was on my plate. As I looked at it, wondering what to do, a lunchroom monitor came over. “What’s wrong, baby?” she asked, hand on my back. “I don’t know what this is,” I said, looking at a soft, slimy green pile running into some pasty mush that seemed to spread and grow bigger by the minute. She pointed to each item, “That’s your ham, collards, beans, and there’s your grits. You need to eat all that before you go play.” I did not eat it and could not wait to get home. At six years old, I felt as if I entered an alternate world where I literally could not recognize the food I was supposed to eat. This unfamiliarity was a harbinger of the more significant differences I would uncover growing up in the South. Many times, those differences were broached with food, such as when friends made me authentic soul food dinners or served me sweet tea and red velvet cake.

In Black, White, and The Grey: The Story of an Unexpected Friendship and a Beloved Restaurant, Mashama Bailey and John O. Morisano share their collaboration in the development of a restaurant in the Deep South. They use the language of food to tell their story of a Black woman and a working-class Italian man coming together to explore the African diaspora, the legacy of slavery, port cities, and the migrations that influence foodways and family culture. Their story shifts and expands the narrative of what American food is and can be, and tracks the emotional landscape of partnering with someone from a different background.

Morisano, a food lover and serial entrepreneur, bought a “dilapidated, Jim Crow–era Greyhound bus terminal” in Savannah, Georgia, with the notion of opening a restaurant. The terminal is located in a no-man’s-land between the touristy downtown and the African American neighborhoods on the outskirts. He sought to harness his sentiment that food is “family, refuge, and love” to explore new stories in a space shaped by discrimination, with segregated waiting rooms, bathrooms, and lunch counters. As he began searching for a chef-partner, he quickly realized that his choice was crucial to truly reenvisioning the terminal that had only desegregated in the mid-1960s. Recognizing the power of symbolism, he sought an African American woman to co-create The Grey, eventually choosing classically trained Mashama Bailey, the sous chef at Gabrielle Hamilton’s renowned Lower East Side restaurant, Prune. Bailey was also running a supper club in Queens at her grandma’s home, as a way to explore and imagine the restaurant she hoped to open one day.

Bailey knew the South, having spent a significant amount of her childhood in Savannah. For the most part, Savannah was a “good place to be a kid.” She remembers diverse neighbors, good food, and the fact that “[t]here were always children outside playing as the old folks watched from their porches or living room windows.” In many ways, her Savannah experience was more diverse than her Bronx neighborhood, where her whole “tiny world had been Black and Brown.” In Savannah, the importance of food and family grew. Both her parents worked and attended college to improve their lot for the family. Because of this, she cared for her younger siblings, preparing after-school snacks for them. A lasting influence was the Sunday suppers that the extended family relied on to spend time together after a busy and fractured week. Morisano’s family also enjoyed Sunday suppers, overseen by his grandmother, with her Italian gravy serving as an emotional salve. Those two hours a week offered an escape from “the battles of a family that thrived on conflict: a father who worked too many jobs and still never had enough money, raised too many kids, and drank too many cans of Schaeffer [sic] on any given night.” Sunday suppers were precious to both families, and Bailey and Morisano sought to create the same nurturing environment for their patrons.

Once the partnership was formed, it was anything but easy sailing. Bailey was not as instrumental in early restaurant design sessions as she should have been; her perspective as a working chef with over 20 years of experience would have significantly enhanced Morisano’s concepts. Bailey abetted this lack of inclusion early on, as she found that growing into the role of a true partner required a strong voice and trust in her co-workers, qualities she was developing. This lack of leadership on her part led to misunderstandings about her level of commitment and several serious arguments. It would be easy to gloss over these disagreements and consider them merely the usual growing pains. By revealing them to readers, sometimes in painful detail, the authors give a little master class on how to lead, dismantle limiting beliefs, share responsibilities, and temper angry outbursts. Stepping into one’s power was essential as Bailey sought not to recreate recipes from the past but to “create new dishes that are personal and invoke memory.”

Recipes based on The Grey’s menu and memorable meals shared by the partners are sprinkled throughout the book. A striking example of how old foodways can rearticulate history is Bailey’s inclusion of the “Thrill” on the menu. Thrills are hyperregional, found in Savannah’s African American communities, such as fruit juice or Kool-Aid frozen in a Dixie cup with a popsicle stick to make an affordable and cooling snack. Neighbors made Thrills to sell to children whose neighborhoods were not on the route of the ice cream truck. The Thrills on The Grey’s menu are smaller and made with higher quality ingredients, but the importance of reclaiming food born out of poverty in a fine dining restaurant cannot be understated. When dishes like organ meat or saltines with butter are elevated, we celebrate our heritage and commonality. It is a near universal experience, the concoction of foods out of meager supplies to nourish and celebrate.

The format of Black, White, and The Grey is unique. Bailey was not interested in writing a book; she was busy running a restaurant, so Morisano wrote the bulk of the narrative. After the manuscript was complete, the two holed up in a Paris apartment to edit and amend their history line by line for a month. Their voices remain separate: his takes up more space, while hers is in bold. The arrangement creates a lively conversational tone. Bailey’s voice is one of correction and perspective. In many cases, she directly contradicts Morisano’s memory of events. She addresses Morisano directly, making readers feel as if we are eavesdropping in the kitchen. Bailey often adds personal context or researched history, specifically about early Savannah and the groups that influenced its founding. She speaks with confidence on these matters, whereas Morisano’s voice is often searching and vulnerable. The book tells the story of starting a restaurant, but what it is really about is two people from different backgrounds learning to trust one another and work together to build something meaningful.

While Morisano’s intentions are noble, the way he comes to understand is often awkward and full of gaffes, such as when a customer makes racist comments to him. Instead of confronting the offending man, he runs back to Bailey and unburdens himself to her, pulling her away from her work to attend to his damaged ego. She barely reacts; this is not a unique experience for her. And it is no wonder she doesn’t completely trust him when he acts in ways that seem overly vulnerable, volatile, at times offensive. His decision to show the internal work of confronting his inherent biases is a bold one: though at times annoying, it is ultimately highly instructive. Through the recounting of his and Bailey’s family histories, readers learn how trauma, abuse, discrimination, even murder planted deep seeds that affected future generations in ways they may not even recognize. The journeys are hard work and fascinating to read about; certainly, they offer more than one might expect from a restaurant memoir.

One of the most striking and frustrating scenes, after so much work has been done to earn trust and become true partners, involves Morisano trying to preserve the original signage demarcating the “colored” waiting room. He wanted to keep a piece of the past to illustrate the history of the segregated bus terminal. Bailey, and others, explained that the racist sign would make people who were traumatized by such signs in the past deeply uncomfortable. Eventually, the sign was altered to say simply “waiting room,” a nod to the future as much as a reference to the past.

The restaurant and the relationship almost did not survive these events. Even with good intentions and many shared interests, there were frequent fights. Trust is a big issue for Bailey, both personally and historically. She notes that Black women are often unprotected in society, and Morisano seems frustrated that she cannot lower her guard. At a breaking point, Morisano writes that they “needed to be straight about our lack of trust — whether our lack of trust for each other was based on race or fear of vulnerability.” This insight is powerful and provides hope that, if the pair can learn to communicate, they can move forward. Bailey writes that her distrust subsided when she “began to exercise [her] voice, [her] power.” Morisano admits, “I underestimated the benefits of what plain ol’ diversity in leadership would do for the trust of our team.” A vibrant working ecosystem is created by bringing more people to the table and letting them talk.

Bailey’s perspective on race, that we “need to keep talking about it, we need to talk about it a lot more,” builds an imperative call to action. Bailey has more to say, and we need her voice and incisive criticism moving forward. Black, White, and The Grey is an appetizer to a much bigger narrative that will hopefully be written by her.

The book begins and ends with chapters about the accidental, gang-related death of the restaurant’s beloved bartender. That death gives The Grey its first real test of providing a community space in between the two Savannahs, a place for gathering and healing. Abstract intentions are one thing, but if we want to work within a diverse community and build something new, we might have to hold hands and go through the fire together. We can get there with hard work, long hours, shared traumas, vulnerability, and grace.

¤

LARB Contributor

Amy Bowers earned her MFA in Creative Nonfiction at Bennington College and recently published work in [PANK], Centered, and Bella Grace. Her essay “Manual” is forthcoming (fall 2021) in A Harp in the Stars: An Anthology of Lyric Essays, edited by Randon Billings Noble and published by the University of Nebraska Press. A native Floridian, Amy now lives in coastal Connecticut.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Beyond Soul Food

A new book explores the wide range and deep history of African-American cuisine.

Talking About Food as Cultural Resistance with Monserrat Jarquín

How the drinking of pulque resists the rhythms of industrial capitalism.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!