Territorial Taxonomy: On Melissa L. Sevigny’s “Brave the Wild River”

Mary L. Holden considers Melissa Sevigny’s “Brave the Wild River: The Untold Story of Two Women Who Mapped the Botany of the Grand Canyon.”

By Mary L. HoldenJune 25, 2023

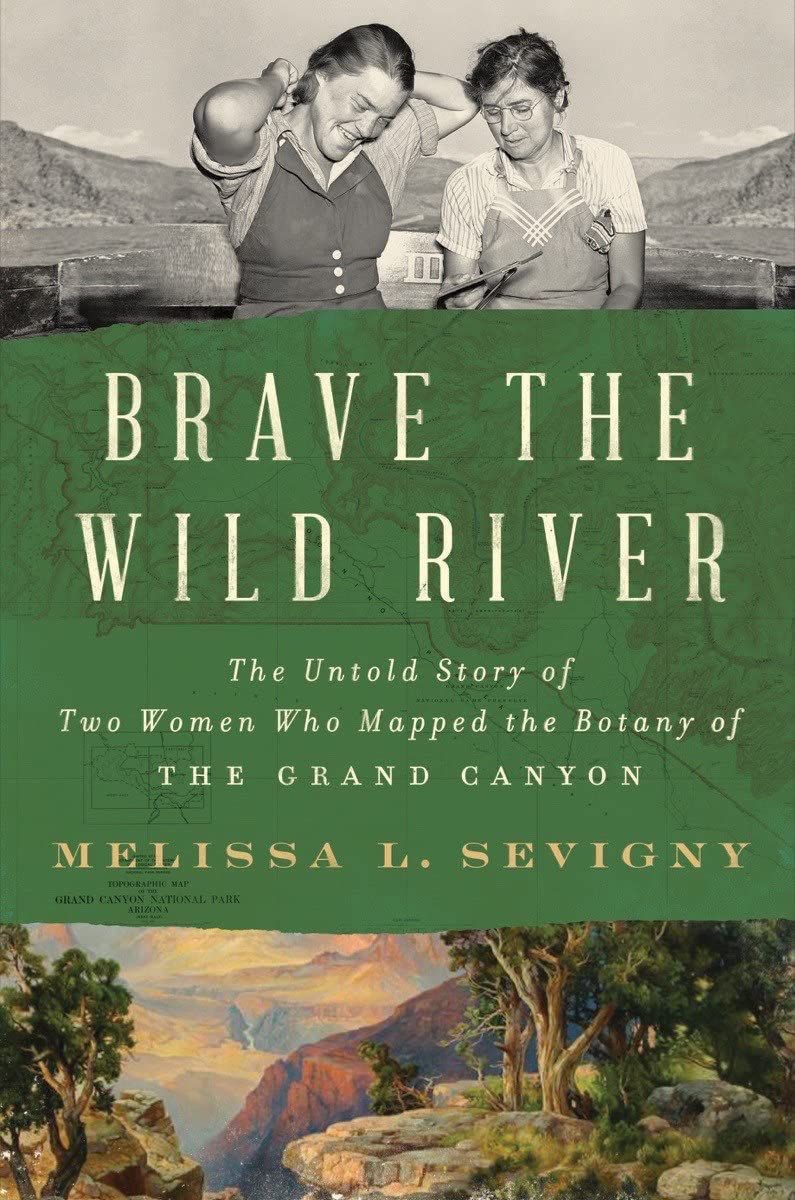

Brave the Wild River: The Untold Story of Two Women Who Mapped the Botany of the Grand Canyon by Melissa L. Sevigny. W. W. Norton & Company. 304 pages.

THE COLORADO River has etched the story of the Grand Canyon into its geological layers. But the intricate stories of its flora were largely ignored by the academy until the painstaking and boundary-breaking work of two female botanists in the 1930s. Now Melissa L. Sevigny has charted their work, and the social and environmental landscapes that they traversed, with her new book, Brave the Wild River: The Untold Story of Two Women Who Mapped the Botany of the Grand Canyon.

Born in 1896 in Nebraska, Elzada Urseba Clover moved to Texas, became enamored with cacti, and went on to earn a doctorate in botany from the University of Michigan, where she then became a professor. Soon she was hatching a plan to botanize the Grand Canyon. But pitching this idea to the men in charge required persistence; fellow professors at the university gave only verbal support. When Clover wrote a grant request for $400 and received only $300, luck brought her to Norman Nevills, a hotel owner in Utah whose risk-taking wife supported the plan—it dovetailed seamlessly with her own goal to build a business guiding raft trips on the Colorado. Nevills needed a maiden voyage, so he enlisted friends to man three wooden boats: the Botany, the Mexican Hat, and the Wen.

Despite their 17-year age gap and differences in personality, Clover recruited Mary Lois Jotter to join the party. Jotter, born in 1914, grew up with a conservationist father in the shadow of the giant sequoia that he had planted outside their California home. Jotter was working on her doctorate at the University of Michigan while Professor Clover was organizing her voyage. The professor wanted help collecting plant specimens, and she felt it was necessary to have another female aboard. Jotter signed on and borrowed $200 from her father to finance her share of the trip.

Although Clover and Jotter were admonished that the Colorado River was a “mighty poor place for women,” the explorers entered the waters on June 23. Whirlpools, boulders, and eddies foreshadowed the rapids to come. Sevigny writes:

They could hear the rapid before they saw it, a low reverberation that settled in one’s chest behind the breastbone, building to a roar. A straight white line appeared, cutting off the plunging V of the river. No hint of what lay beyond except for the white curls of water that leapt up from behind the brink, dolphin-shaped, and dropped down out of view. The current slowed, flecks of foam swirling on its surface, and then, as if released from its hesitation, leapt forward over the edge. This was Badger Creek Rapid, eight miles downriver from Lee’s Ferry.

When the rapids gave way to a sandbar, they discovered Vasey’s Paradise at river mile 30, where moist red soil gave life to scarlet monkeyflower, Western redbud, horsetail, watercress, side-fruited crisp-moss, Stansbury cliffrose, and Longleaf brickellbush.

The boating party docked at this natural garden on a cloudy late-June morning. Clover and Jotter jumped out of a wooden boat and “collected furiously,” while their boatmen showered under a waterfall and then waited for the women to make and serve them lunch. “We have spoiled them completely,” Clover wrote in her journal.

International news services covered the trip because the botanists were also the first two women to travel the length of the river and survive. Passion for botany was their bond, and their physical strength matched their willingness to persevere. They appreciated wise guidance and forgave mistakes, even as errors made parts of the trip strenuous or dangerous.

Despite the subject matter, only a few black-and-white photos of plant specimens are included in this book. I wondered, “What are the plants of the Grand Canyon?” and sought color images in other books and online. At various points, I stopped to examine my nature literacy and measure my plant vocabulary.

Still, Sevigny paints a picture by describing other elements of the canyon journey: quicksand, mud, insects, the necessity of canned food, the constant of wet fabric, the wood and paper frames used for pressing plant cuttings, and the taste of unfiltered river water on the tongue. She goes beyond botanizing and writes about the ancestral Puebloan residents of the area, mapmakers, former explorers, honeymooners, rescuers, professors, parents, siblings, newspaper reporters, filmmakers, and tourists.

When the narrative rapids slow, Sevigny leaves space to further speculate about the era, the people, the river, and the environment. The book’s title hints at her writing wizardry with the word untold. I wanted to fill in the still untold ways that emotional intimacy occurs between people who share grand adventures that involve missions, business, the advancement of science, and the betterment of humanity. Many significant stories from the past remain untold. A few of them involve rivers, but most involve the accomplishments of women.

In the book’s last chapter, titled “A Woman’s Place,” Sevigny cites a truth:

The same challenges that Clover and Jotter confronted decades ago remain barriers for women in the sciences today. […] A recent study found that it will be another two decades before women and men publish papers at equal rates in the field of botany, a field traditionally welcoming to women.

By page 290, the story is, for the most part, no longer untold. Clover and Jotter meticulously collected and categorized the Grand Canyon’s flora at a pivotal time in the earth’s history. It took two female botanists to conduct a baseline mammogram of the Grand Canyon’s vascular plants at a time before the term climate change really meant climate damage.

¤

LARB Contributor

Mary L. Holden, a freelance editor and writer in Phoenix, is the author of Yavapai: 12 Poems in Honor of Arizona’s Centennial, 1912–2012. She will self-publish a novel, Quail: A Lifetime in the State of Arizona, in late 2023.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Photic and the Deep: On Sabrina Imbler’s “How Far the Light Reaches”

Michael Scott Moore reviews Sabrina Imbler’s “How Far the Light Reaches: A Life in Ten Sea Creatures.”

Is Stealing Redwoods Sometimes Okay?: On Lyndsie Bourgon’s “Tree Thieves”

Jeff Wheelwright reviews Lyndsie Bourgon’s “Tree Thieves: Crime and Survival in North America’s Woods.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!