Surrealism in Our Time: On Katya Kazbek’s “Little Foxes Took Up Matches”

A Russian folktale becomes the foundation for a political satire.

By Anne GoldmanMay 13, 2022

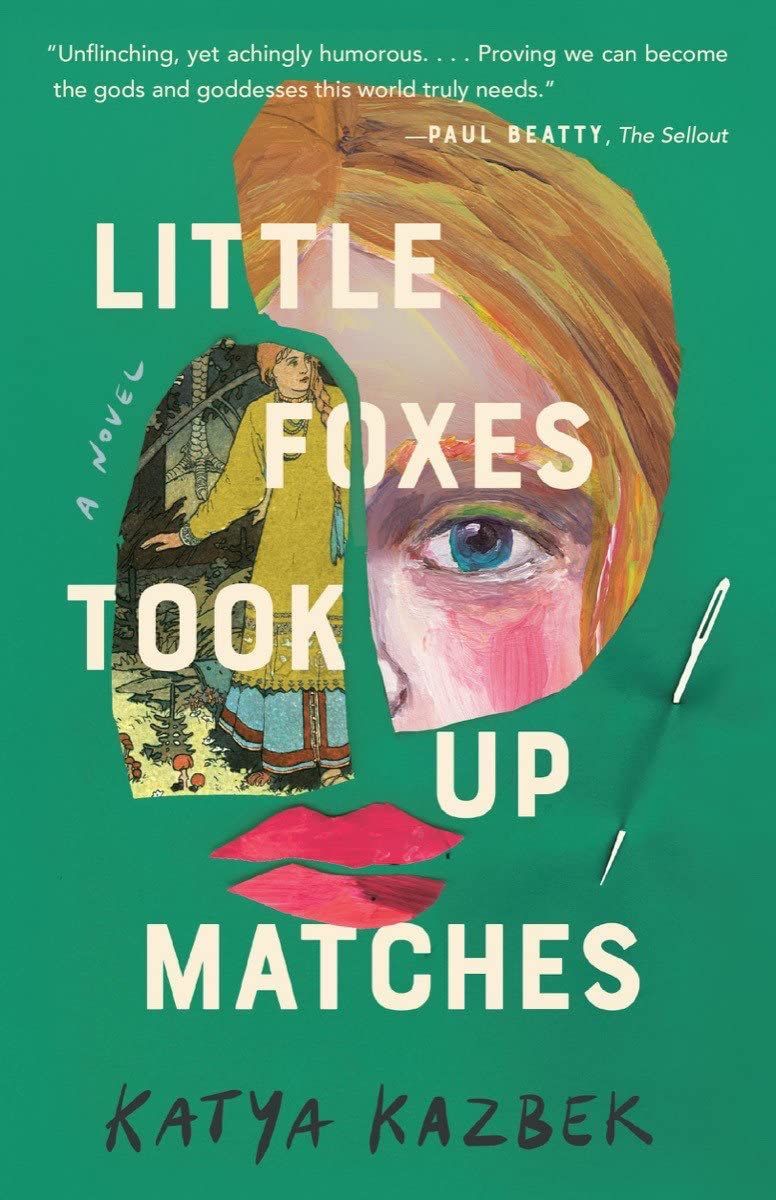

Little Foxes Took Up Matches by Katya Kazbek. Tin House Books. 350 pages.

HOW DO WE acknowledge political violence from afar without reducing ourselves to spectators? Facing the pain done to others through the lens of the documentary camera is tricky, as Susan Sontag has famously argued. But there are other means by which we can witness suffering rather than merely watch it unfold. Katya Kazbek’s debut novel, Little Foxes Took Up Matches, offsets a gritty story of Russian political turbulence in the 1990s with the dreamy retelling of a classic Slavic folktale. But the book calls upon magical realism less to divert readers from history than to focus us upon it.

We come to grips with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the growing pains of the new Russia through the eyes of the earnest young Muscovite who is its central character. Schooled in fairy tales alongside Pushkin’s poetry, Mitya understands magic as a condition of being. The mythic character Koschei survives by entrusting his soul to a needle that he hides in animals, nested one inside the other like Russia dolls.

There’s a needle inside Mitya too: at two years old, he swallows one while under the desultory care of a grandmother who is intent on shoring up her tatty status as a member of the intelligentsia, even as she takes in American soap operas on Russian TV.

Mitya’s family is under pressure. His parents scrabble to prevent downward social mobility from turning into free fall. Their success is mixed. But he develops into a buoyant and wide-eyed teenager anyway, thanks to friends who guide him through political labyrinths that adults refuse to see.

Mitya may be a romantic like his grandmother, but he’s not immune to irony. Kazbek introduces his perspective in dryly bemused sentences that sustain as they inaugurate the novel:

It all began when the Soviet Union was still united, which was, by the accounts of everyone around Mitya, a much better time. He couldn’t know for sure because the events surrounding the USSR’s collapse were about as dim as anything that happens in one’s childhood. So Mitya was forced to trust the words of adults until he knew better.

In his preteen years, Mitya is understandably hazy on history. But he is wise enough to cling to the Koschei story, even as the family TV blares stories of the rich and famous to drown out the noise of viciousness in the streets.

Kazbek is in conversation with other Russian American bildungsroman writers, like Anya Ulinich, Lara Vapnyar, and David Bezmozgis, who often situate characters where the wild things are. Mitya has plenty of reason to listen to creatures that bark, chirp, and rustle. His father venerates soldiers and plies his son with toy guns and “an accurate, scale model of the tank that he had operated in the Afghan War.” Mitya steadfastly chooses cosmetics over these icons of conflict. One evening, Dmitriy Fyodorovich comes home saddled with frozen food bought at half-price from a supermarket in the throes of a power outage. He does not so much surprise his son as intercept him “dressed as Ariel the mermaid from the foreign cartoon.” Beat about the head with “two frozen-solid chicken carcasses,” Mitya is left with a “hot numbness.”

The scene toggles artfully between perspectives, starting with kitsch and concluding with an image less arch but more startling. When Mitya collects the food strewn on the floor, the chickens have begun to thaw, and his fingers leave “indentations in the top layer beneath the plastic.” Before putting them in the freezer, he kisses the dead things and leaves “traces of lipstick on their white striped packaging.” The child’s angle of vision swerves away from the polish of satire’s surface brightness. If this outlook is raw and awkward, it is also memorable, providing what feels like direct access to the experience.

While Mitya is often under attack from his disappointed father, he is serially abused by a cousin who has come home from war and with whom he must share a bed. Unlike his damaged relative, Mitya keeps an open heart, venturing out to negotiate the confusion of young adulthood during a perplexing time in which making do, for the majority, gets trickier by the day.

Kazbek limns the pain that people endure when their sexuality is considered a “deviancy.” But this book does not dwell in suffering for its own sake. Instead, it sustains a curiosity that is consonant with its appealing central character. The best writing here — because it is most finely observed — summons the ordinary rather than the magic we invoke to displace it.

Pigs don’t fly in this novel. They come beheaded and withered in the market. Kazbek details the one Mitya sees: “[P]ink, with touches of red where the air had dried it out, and where the blood vessels appeared through the translucent skin. Its hairs were sparse, thin and white like an ancient man’s[.] […] The skin felt human, too, only thicker.” The passage is arresting not only because Mitya understands the animal as a memento mori but also because its head is rendered with the close attention that paradoxically accords it vibrant life. Kazbek describes other objects with the same fine eye: blood on pavements and mixed into chocolate bars for nutrition, the “teeth marks” Mitya leaves on his mother’s lipsticks, the “cracks in the corners of his mouth,” a New Year’s dinner of fish and clementines — “citrus mixed with the gasoline aftertaste of the sprat oil.”

Effluvia, viscera, tastes edged with acid and iron: Kazbek comes to grips with the ooze and stink of which we and the world are composed. This book is less about magic than the strangeness of the quotidian, a strangeness heightened because it is narrated from the perspective of someone who has not yet learned to accept the casual cruelty of Russian life around him.

The Koschei retelling is pallid compared with reality’s becalming horror: people transformed not into Narcissus blooms but snowdrops when their bodies are discovered under melting ice, the violence of gangs whom friends older than Mitya knowingly refer to as, “[l]ike, you know, in the kids’ poem, ‘Wolves […] so afraid, they ate each other’s heads.’”

Like the vision of fascist Spain we obtain in Guillermo del Toro’s 2006 Pan’s Labyrinth, the political realities of 1990s Russia in Little Foxes Took Up Matches issue from the mouths of babes. In both, children use the language of surrealism to explain why things hurt. Mitya’s friend Zhenya feeds McDonald’s fries fished from the garbage to baby rats in the basement of her apartment building. In a Disney fable, she would be a Cinderella living in a garret whose pumpkin coach doesn’t arrive, but the frisson here is straight out of Orwell. Mitya finds it odd that Zhenya spends time caring for rodents that will soon eat poison laid down by exterminators. Understanding the parable applies to people, we are less surprised.

Though the constant clicks of lenses offer us LED simulacra, literature reminds us that the world is beyond capture. With Mitya, Katya Kazbek describes a person who refuses to “constrain” himself to convention and who might grow up “without abandoning his childhood.” “Children, like animals, use all their senses to discover the world,” Eudora Welty writes in One Writer’s Beginnings (1984). “Then artists come along and discover it the same way.”

Little Foxes Took Up Matches occasionally fumbles its stilted dialogue. But this book is not easily forgotten. Replete with images as immersive and clear as shocks of icy air, it returns readers to the state of stunned wonder that is the world of childhood — in retrospect, at least, the original fable for each of us.

¤

LARB Contributor

Anne Goldman is a professor of creative writing at Sonoma State University and the author of Stargazing in the Atomic Age (2021), a Kirkus Best Book of the Year.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Conjuring in Wartime: Colm Tóibín Evokes the Art of Thomas Mann

A novel about the life of Thomas Mann is a huge canvas, finely observed.

Blind Curve Ahead

Rachel Kushner rides a motorcycle close to the edge.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!