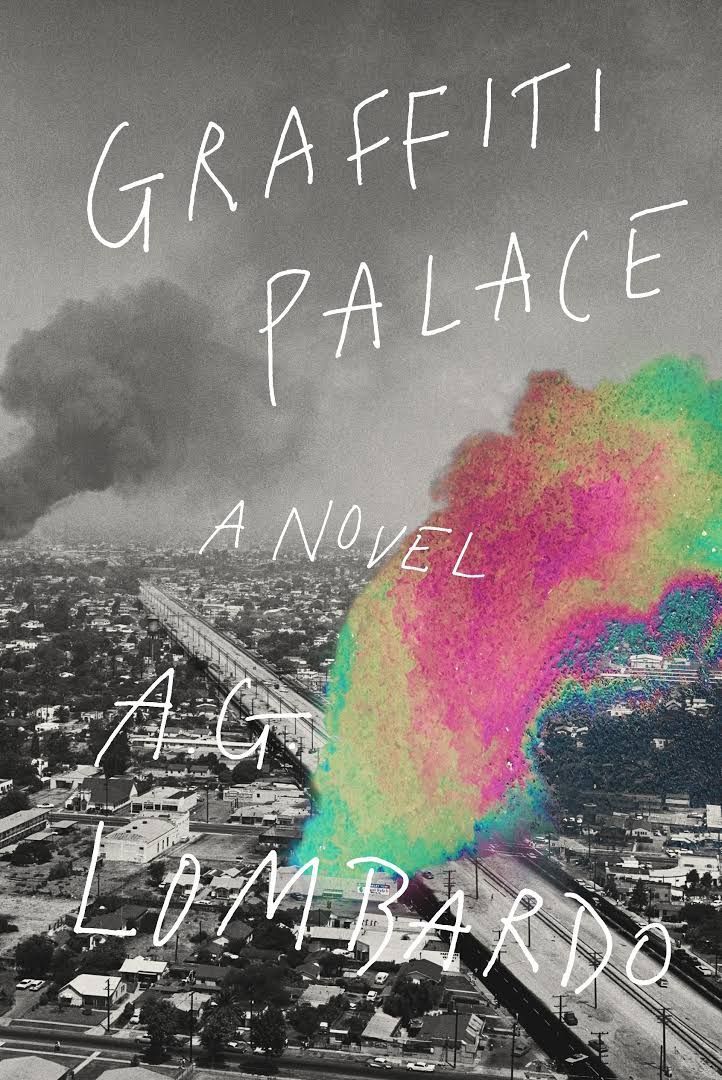

Subversive Surfaces: “Graffiti Palace” by A. G. Lombardo

John Flynn-York on A. G. Lombardo's debut novel, "Graffiti Place."

By John Flynn-YorkMarch 13, 2018

Graffiti Place by A. G. Lombardo. MCD. 336 pages.

A. G. LOMBARDO’S searing novel Graffiti Palace revels in an abundance of language. I take pleasure in that approach, and so welcomed the play of sounds and images. Consider this description of shipping containers at the Los Angeles Harbor: “A city of iron cubicles latticed along the harbor, piled like a giant’s stairway in gravity-suspended steps rising toward the burnished sunset, or skewed in angles and intersecting layers; some pitched, half-toppled by long-ago extracted cranes and ship’s booms.” It resembles the scene it describes, dense with shapes, colors, and history; there’s rhythm to it, restlessness, and it modifies and complicates itself as it goes. It builds from concrete imagery, rises into abstraction, then topples back down into the real. Like Icarus, we might say — but here, the fall is intentional.

Graffiti Palace is set during the Watts riots, and concerns, mostly, a journey across Los Angeles by Americo Monk, an “urban graphologist and graffiti semiotician” who records the city’s illicit signs in a notebook he carries everywhere. As the novel opens, he’s at 112th and San Pedro studying a traffic signal. His pregnant girlfriend, Karmann Ghia (yes, like the car), is hosting a rent party at the Los Angeles Harbor, where the two of them live in a maze-like assemblage of shipping containers. In Watts, police use unnecessary force during a traffic stop, sparking civil unrest and sending the city into a spiral of destruction fueled by long-simmering racial tension. Buildings burn, news crews report on the “senseless violence that rules the night,” and the police respond with brutality, roadblocks, and curfews. Monk, trying to get home, makes his way south through a landscape of fire, ash, and smoke. But the riots — of which Monk is, mainly, a neutral though sympathetic observer — make progress difficult.

Monk’s travels are picaresque, zig-zagging through southern Los Angeles and throwing him into the company of gang members and cops, musicians and exterminators, seers and novitiates, artists and radicals. He traces a tricky line: he’s neither wholly black nor wholly white, and can appear, depending on the light and time of day, Mediterranean or African, Caucasian or Arabian — “a walking Rorschach mirror that perhaps reflects more of the beholder than the subject,” as Lombardo puts it. Monk’s notebook of graffiti makes him of interest to gangs and police alike. At various points, he is held hostage, given food and drink, interrogated, and offered various drugs, though he mostly refuses to partake. Meanwhile, Karmann grows increasingly worried. The party rages around her. Night passes into day, day back into night. She chases people away from her phone, hoping to hear from Monk, and fends off the approaches of multiple suitors.

Karmann is a latter-day Penelope, a baby Telemachus in her belly, and Monk is Odysseus, making his way back to the harbor while Los Angeles writhes in agony. Buttoning the story to the spine of the Odyssey serves the novel well. Without that structure, the story might collapse under its own weight, too many characters, too many details, too many vectors of movement. Instead, it is improbably resilient, deriving narrative energy from the series of trials Monk undergoes, many of which have clear links to Homer’s epic: lotus-eaters in Chinatown, a cyclops in the tunnels under Los Angeles, a fortune teller near the Harbor Freeway. These connections work best when they’re dense and layered, operating as conversations and arguments with the source; when they’re on the surface, or treated as jokes, they’re less effective, pinging the reader with the thrill of noticing them without doing the harder work of expanding the range of Homeric tropes. At one point, Monk is in the back of a Corvair when he hears angelic singing coming from a nightclub, “a soul aria that seems out of this world.” He tries to get out, but he’s strapped down by the unfamiliar mechanism of a seat belt, still somewhat new in 1965 — Odysseus lashed to the mast as his ships sails past the island of Sirens. “Honey, you don’t want to go in there,” the driver says to him. “Them girls are so hot you’ll never leave.” It’s funny, but feels a little gratuitous. Then again, the episode of the Sirens is among the most recognizable moments in the Odyssey, and treating it in an offhand manner is perhaps the best way of paying homage.

The interpretative framework of the book coalesces in Monk. He’s a guide to the city as much as he is a traveler of its streets, and his explications of graffiti illuminate the meanings hidden in the gang signs, murals, stencils, and culture-jamming stickers stuck over advertisements. But Monk is also aware that this world is unstable, precarious: “He knows that sometimes signs are like the new physics, that the rules break down; the semiotician struggles in the twilight of uncertainty: message, sender, receiver, meaning can shift, change in time and space.” Communication is always contextual, always contingent, and the discrete order of the system that makes interpretation possible can disintegrate at any moment. Recording the signs and stories is, therefore, also an attempt at preservation:

This city is always changing, shedding its skin of underground signs and languages in paroxysms of destruction and rebirth, seething in a secret war between the dispossessed, who write its street histories, and the cops and power structures, who destroy unsanctioned communication through anti-graffiti paint crews and incarceration and intimidation: he will be their historian.

Along with his catalog of graffiti, Monk collects stories, preserving the city’s counter-narratives. In Chinatown, Monk hears the story of the invention of the fortune cookie from a man named Shen Shen. On 127th Street, Monk runs into Miss Iva Toguri, who, once upon a time, was accused of being a “Tokyo Rose,” the name given by GIs to the English-speaking women who broadcasted propaganda over Japanese airwaves in World War II. In an alley off Athens Way, he stumbles into the home of a woman who calls herself Queen Mab (“I’m not Mercutio, am I?” Monk jokes). She spins a story of slavery and emancipation laced with magic, runes, and secret societies. These stories, as related in Graffiti Palace, cannot be taken at face value. It’s true the fortune cookie was invented in San Francisco; it’s true a woman named Iva Toguri was put on trial for treason, though her trial was a travesty of justice and she was later pardoned; Queen Mab, for her part, is Circe (maybe) by way of Shakespeare. But Lombardo’s versions of these stories are, like graffiti, exaggerated and colorful. His rendition of the history of fortune cookies mixes in haiku and the dozens. Miss Toguri’s story is supplemented by invented details. As for Queen Mab’s version of history, who knows? Even Monk is skeptical.

It would be satire — the exaggerated characters, the wild stories — if it were not so clear that the book’s empathy is with the disaffected. During the riots, Monk is accosted by a white newscaster, Brey King (the pun in her name — “breaking news” — is characteristic of the writing), who wants to know why people are rioting. Monk’s response:

“Ah, social inequalities, I guess,” softly. “The inherent racism of a police force that’s trapped in a Jim Crow past.” Monk, realizing that being interviewed about the cops on TV is probably light-years from cool, slinks away. He scowls back at the white woman: What’s the use talking to white people? He knows he shouldn’t think like that, boxing her into some kind of simple racial equation, but she and her kind, aren’t they doing the same thing to him? Most of the time the only communication between whites and blacks seems to be self-conscious, patronizing chatter about race … spoken words are signs too, and these feeble attempts at communication from the White Power Structure — the WhiPS graffiti copied in his notebook — are really miscommunication, static that walls in ignorance instead of tearing it down. Monk frowns: perhaps there is a limit to empathy, a gulf that can never truly be bridged between others.

The satirical impulse, however, sometimes wins out, and takes the writing too far in the direction of caricature, like when a Chinese character’s speech is rendered with l’s replacing r’s. This feature of speech is so charged, so coded, that presenting it in this manner seems unnecessarily provocative. Many other characters in the novel, who are of a vast rainbow of ethnicities and backgrounds, also have their speech rendered phonetically (and use slang and nonstandard diction to boot), and other Chinese characters in the novel do not have their speech written in the same way — so the impulse is both universal to all and particular to each, and, it would seem, not derisive or scornful. But this, in particular, could have been handled better.

Lombardo’s style is a heightened one: it’s noticeable, draws attention to itself, revels in synonyms, metaphors, and exaggeration. The idea is, I think, not to show off the writer’s skill, any more than other artists who work in styles that are insistently present. Instead, it’s staking an aesthetic and philosophical claim that fiction can represent the lushness, diversity, and overflowing-ness of life — the abundance of both good and bad, large and small. In this, of course, Graffiti Palace is not alone. It’s in a tradition that includes Thomas Pynchon, Toni Morrison, and the Herman Melville of Moby-Dick (the Melville of “Bartleby, the Scrivener,” less so), writers who otherwise have very different concerns and approaches. And that is only to name a few writers, and only American ones. But this aesthetic of linguistic plenitude runs counter to a significant strain of American thinking about fiction, which emphasizes clarity, compactness, and terseness, the Protestant ethic made manifest not just in stories but in the very way they are told. It is therefore refreshing to encounter a writer going against that minimalist grain, making an argument for an aesthetic based in something other than cold hard gems of closely observed fact, written sparingly — which is not to dismiss that style of writing, but to say fiction is large, it can (and should) contain multitudes.

This style is not a simple celebration of life’s variety and richness. It’s the plenitude of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme: there’s a lot going on, often teetering on the edge of cacophony, threatening to plunge headlong into the abyss, with only a few stray lines of melody as a guide through the chaos. Lombardo’s most obvious literary forebear in this regard is Pynchon, and his text bears traces of Pynchon’s influence. Characters sport absurd, quasi-synedochical names; ellipses dot the text like pepper; and there are insinuations of unseen and unknowable forces at work. And, like Pynchon, Lombardo often elides dialogue attribution or replaces it with a participle: “‘Look, Officer Trench, you know me,’ Monk trying to control the fear in his voice, ‘it’s just graffiti, art stuff, a hobby.’”

The attention to the surface of the text echoes the book’s use of graffiti, which here becomes a multi-headed metaphor, a palace of possible meaning, and a method of subverting overarching narratives. Around halfway into Graffiti Palace, Monk comes across Jax GK — short for “Giant Killer” — and his partner, Sofia. Under cover of night, they attack billboards with spray cans, stencils, and stickers, transforming messages of domestic bliss and unthinking consumerism into indictments of the same. Out on a run with them, listening to the radio, Monk is perplexed by a white talk-show host’s anger: “What the fuck do they have to be angry at? People driving in their cars, isolated, through all these streets and freeways, listening to these fools … no wonder everyone’s pissed off and insane, afraid of everyone else.” Sofia’s response: “They clog all our senses with their propaganda. […] Eyes, ears … they’d inject their lies or wire our brains if they could figure out how, but we’ll take it back, one street at a time.”

Ultimately, Graffiti Palace itself is a performative resistance to authority, channeling the multiple contrasting voices and stories of Los Angeles into a mural exploding with color and contradictions. Or, perhaps, a building covered in illicit signs and arcane symbols:

Too many dots to connect … it’s vertigo, any patterns that seem to coalesce only fade like shadows: sometimes he’s sure the city is one giant graffito, a sprawling, urban uber-text that one day, with enough notebooks, he might unlock to reveal all its hidden codes. Sometimes the graffiti in his thoughts and notebook blur into the city’s spray-painted icons, until his mind and the streets seem like one vast network of rainbow messages, the convolutions of his brain and the corridors of the city fused into one myriad, fantastic structure, like a palace of graffiti.

¤

LARB Contributor

John Flynn-York writes fiction, essays, and book reviews. He is a co-founder and editor of Automata Review, and holds an MFA in Creative Writing from UC Riverside–Palm Desert.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Frantic Transmissions: On Kate Braverman

On a quintessential Los Angeles writer.

Riot/Rebellion: The Legacy of 1992

Steph Cha interviews Gary Phillips, Jervey Tervalon, and Nina Revoyr about the legacy of the 1992 Los Angeles “Riots.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!