Spectacles of Repression: On Netflix’s “Beef”

Amanda Walujono reviews Netflix’s new dramedy “Beef.”

By Amanda WalujonoJune 30, 2023

MAKING A PUBLIC spectacle of ourselves is one of the few opportunities we have to display our raw emotions to the world. When we raise our voices and unleash all that is within, our rage, horror, and loathing become palpable to every passerby. Our shouts, our screams, linger in the air after the scene has ended—they are potent, impossible to ignore.

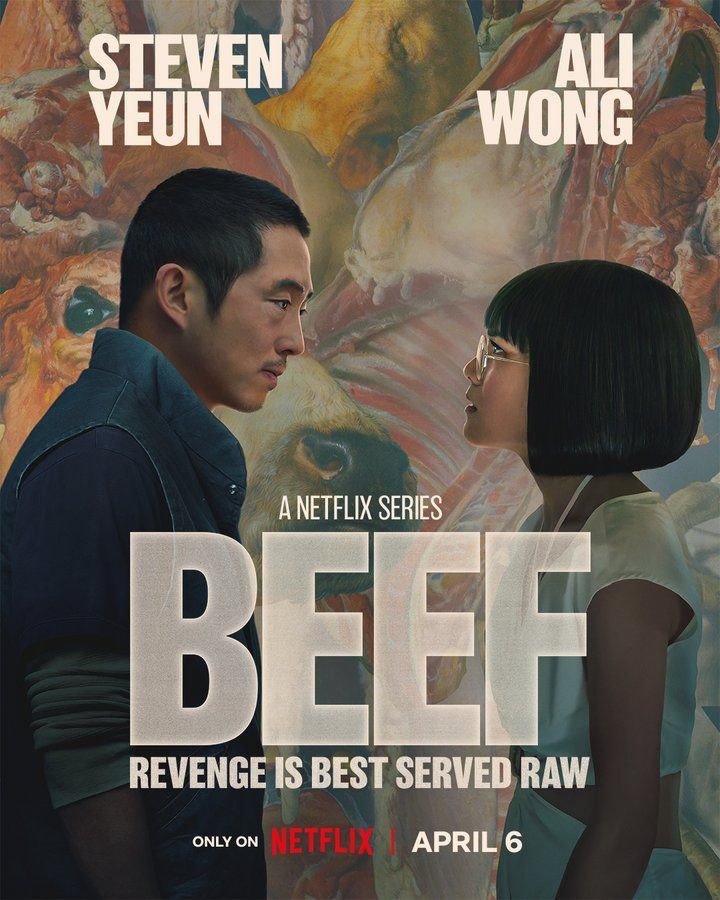

Netflix’s new series Beef starts off with just such a public spectacle, an incident of road rage that leaks in unexpected ways into the lives of Amy (Ali Wong, best known for her stand-up comedy, skillfully deploying both zappy punchlines and dramatic chops) and Danny (Oscar-nominee Steven Yeun, a tour de force). After some screeching brakes and one flipped bird, these two strangers’ lives are rocked by explosion after explosion of their own making. Outlandish plot points may weave throughout (the first season contains both an art heist and a church burglary), but at its messy beating heart, Beef is an empathetic character study that takes every emotion seriously in a world that does not.

A few years ago, I had a running joke with my fellow Asian American friends about “Asian repression,” most of which were targeted at EDM-raving Asian Americans we knew and observed. We pathologized them as former do-gooders who were letting loose in the freedom of adulthood, their repression flaring up, overcompensating with drugs and bottle service in Vegas. But behind every joke, there is a kernel of truth: implicit and explicit stereotypes that paint Asians as “meek,” “robotic,” and “submissive” have led many Asian Americans to repress anything that is bothering them. This is not to say that suppressing emotions is exclusive to Asians—everyone has a public and a private face to some extent, and we all do our best to avoid becoming the public spectacle of the day. But it’s different for us than it is for, say, a passive-aggressive white Midwesterner: Asian emotions are racialized in a way that white emotions are not.

With this dynamic at its center, it’s easy to see where Beef could’ve gone wrong. A lesser show would attribute Amy and Danny’s tamped-down emotions solely to everyday microaggressive racism or generational trauma from immigrant parents. These narratives, while resonant, are territory well trod in Asian American personal essays, fiction, and other forms of media. Thankfully, Beef is both self-aware and fluent in its therapy vernacular. Indeed, its ethos is laid out in a nugget from an actual therapy session: “[A]cknowledging this is just the first step. In order to create new neural pathways, we have to uncover what lies underneath our awareness.” Throughout its first season, Beef continuously makes the choice to delve deeper into Amy and Danny, with empathy and recognition, while not absolving either of wrongdoing, until we reach a place that’s more emotionally raw and deeply specific than anything else in the current television landscape.

(Please note that this essay is an analysis of the show Beef as a work of fiction, and does not delve into the reprehensible comments of actor David Choe and the surrounding real-life controversy or the handling of it by the creatives involved.)

The very first shot of Beef is a void, a blank screen beneath which we hear the interaction between a cashier and a customer in line ahead of Danny at the store. It’s a pleasant, normal interaction that seems unremarkable. It’s when the camera cuts to a close-up of Danny’s face that we are clued in that something is amiss. Danny’s expression betrays a heaviness, as if the last light in his eyes is about to fade out.

We linger on this close-up for a while, seeing the impatience, agitation, and dread scroll across his features as he is waiting. He is like a ticking time bomb, barely holding together an acceptable public facade, ready to detonate at any moment. When it is finally his turn, Danny tries to get through this customary but mandatory interaction as quickly as possible. Before it’s even begun, Danny already seems on the defensive, as if he is bracing himself for impact.

The world seems to be against Danny, and just as it is for many of us, it’s other strangers’ mild annoyance at our presence that can feel decimating. Danny’s unpleasant customer interaction—a failed attempt at returning three hibachi grills—forces him to seek refuge in his car, presumably a safe space. Our vehicles are one of the few spaces we have left in modern society for privacy, even if most of us can’t afford to have our windows tinted. They are sacred spaces where we can indulge our vices: smoke up, blast our favorite songs, and eat fast food, away from anyone else we may live with or to whom we are responsible. But even this sacred space of Danny’s is violated when he almost backs into Amy’s car. It’s in this moment when the show truly begins.

Later in the pilot episode, the unreturned hibachi grills reappear. We see Danny locked in his room, surrounded by the flaming grills, big boxes lining the scene like the pillars of Stonehenge. We hear his thoughts in a profane voiceover: “Nobody understands. Fuck you. You don’t even know.” At this point, he sounds like he is holding back a sniffle, as if he’s been crying. “And when I’m dead, you’ll see. You’ll fucking see.” We then understand that this voiceover is an excerpt from his suicide note. He has attempted three returns of the hibachi grills (and carbon monoxide detector), and now this is his fourth attempt at one of the “least painful ways to kill yourself” (as we see from his Google search result). It’s a cruel but human twist, a twist I hadn’t seen coming but which made perfect sense in retrospect.

When you are deliberating whether to end your life, you walk through the world like a wounded animal. Almost anything can set you off because you spend so much of your energy trying to make it through the day without incident, passing yourself off as “acceptable” to society, even though you don’t feel worthy to live. The smallest things can be misread as signals that the world wouldn’t miss us if we left—as motivation for doing the unthinkable. It’s why Danny’s safe space inside the car was so important: it was a place for him to remember to literally breathe in and out, when he at times wanted to stop breathing forever.

Danny doesn’t go through with his suicide attempt. Shortly after he relents and opens a window, he decides to dedicate himself to a new passion, one that tethers him to this earth—destroying Amy. While he doesn’t tell anyone else about his suicide attempts, his little brother Paul acknowledges at one point that Danny has been depressed for a long time. It doesn’t help that, like many Asian Americans and Asian immigrants, Danny believes that “Western therapy does not work on Eastern minds,” a refrain repeated a few times throughout the season. But as we watch Amy and her Japanese American husband George’s relationship unravel, with the help of therapy, it appears that Danny perhaps does have a point.

¤

A surprisingly significant plot point in Beef is that Amy keeps masturbating with a gun. In the third episode of the show, Amy and George find themselves at a couples counseling session with an Asian American female therapist, Dr. Catherine Lin, to talk about this odd conduct. Though Amy and George both embrace modern-day millennial mental-health culture, they are opposites down to their sartorial choices: George is enveloped in a luxurious but ordinary soft-knit cardigan of organic fabric while Amy is wearing Issey Miyake’s Pleats Please, which is synthetic, practical, easy to mold, and durable with its knife-like folds.

George, who like many millennial men is familiar with weaponized therapy jargon, tells Lin, in a mawkish tone, that they’ve “gotta dig a little deeper” into Amy’s issues. But when it is Amy’s turn to speak, her voice almost trembles with sincerity as she talks about her dad, a “Chinese guy from the Midwest. I mean, communication wasn’t his forte. He’d just bottle up everything inside until it just exploded out at once.” And her mom: “She wasn’t any better. She thought that talking about your feelings was the same thing as complaining.” Thankfully, Beef avoids treacliness by intercutting Danny (a first-generation Asian immigrant himself; we later learn that he moved from Korea when he was a child) losing his shit as he tries to scrub off the graffiti Amy left on his truck, unleashing guttural screams of fury while kicking it.

Amy continues with her mom’s backstory that, while undoubtedly true for many Vietnamese refugees, also neatly fits into American imperialistic narratives about Vietnam and other “Third World countries” during the Cold War era: “She told me the first time she heard birds singing was when she came to America, because during the Vietnam War, they ate all the birds.” Her delivery hits like a muted punch line from one of Wong’s Netflix stand-up specials, stripped free of her stage persona’s volume, abrasiveness, and irony. Amy asks: “Can you imagine what that does to a person? No birds.” Amy then declares to George and the Asian American therapist that “growing up with [her] parents taught [her] to repress all [her] feelings,” and George congratulates her on a “breakthrough moment.”

But this breakthrough isn’t satisfactory to the audience or the other characters. Even Lin’s reaction to Amy is that this is “very … self-aware.” But Amy is convinced that she has discovered her answer: “[I]t all comes down to parents, and I’m excited to dig into that.”

When we finally meet Amy’s parents, the emotional digging doesn’t go as Amy expects. She is shocked to see a photo of her parents “making out in front of the Louvre”—a nice sendup of the trope that Asian immigrants are not outwardly affectionate. While Amy has been gone, her parents have been traveling all over Europe. “It’s been a fun couple of years,” her mom happily declares, and Amy’s shock is clear.

This rightfully puts the onus on Amy for not keeping in touch with her parents, not making an effort to get to know them as people outside of their relation to herself, which is something I’ve seen happen often among many young people, regardless of race or ethnicity. As her dad says, “If you had stayed in touch, you’d know all this.” In response, Amy brings up how she paid off her parents’ mortgage, implying that she has already done her part to play the role of “dutiful Asian daughter,” and now she gets to wash her hands clean of them.

Amy’s dad continues with this parody of Asian American familial clichés, at one point neatly summing up the stereotypical immigrant narrative in one line: “We provided; we sacrificed; we moved here just for you.” Implied but not spoken is the question, So why are you so ungrateful? And after Amy hits her dad back with the low blow of “you didn’t even wanna have me,” he delivers the final eviscerating response: “We’re proud for all your success, okay?. It was nice to see you”—an obvious subversion of the common Asian American narrative that we just want our parents to tell us how proud they are of us. These tropes have always been hollow and saccharine. As Amy’s dad’s words land with a thud, Beef shows how these clichés simplify complexities into a digestible, easy catharsis.

Not that Amy, a disciple of Western therapy, doesn’t try for easy catharsis. When she confronts her mom later, Amy tells her: “This is the problem with our family. We never talked about anything openly.” She continues with a series of verbal jabs that sound overly rehearsed and trite: “I wished you’d talked to me, growing up. […] More and more when I look in the mirror, I see you and Dad, and I hate it.” And she says she feels like the product of “generations of bad decisions sitting inside” her—a.k.a. of Asian immigrant generational trauma.

Luckily, her mom cuts Amy’s righteous screed off with a sage piece of advice: “You’ll realize this as you get older, but if you look back all the time, you crash.” While listing off the different ways her parents have wronged her, Amy also forgets to consider the humanity and agency of her own parents, something I’ve sadly seen many Asian American writers, artists, and creators do when they box their parents into simplistic narratives. We may not agree with everything Amy’s mom does, such as when she recommends that Amy put her marital problems behind her, but there’s no doubt that Amy’s mom and dad are in a relatively happy and healthy place today—despite their issues with their daughter.

After all, there’s only so much self-pathologizing we can do before we paralyze ourselves. In my early twenties, I spent years on the I-405 and I-10 freeways replaying some of the most emotionally traumatic events of my life (which, like Amy’s, also involved my immigrant parents) in a mental loop, until I found myself gasping for air, metaphorically yet also somehow physically drowning. Looking back, I used my own tragic backstory as a crutch, and stunted my own growth for the first half of my twenties while stewing in anger and despair. Amy gleefully embraces the first step of acknowledgment but stops there. The more she can pathologize herself and her parents, the more she can absolve herself of her sins. And that’s why she’s the one who needs to hear Danny when he declares, in the brilliant season finale, that “Western therapy does not work on Eastern minds.”

¤

At the start of the 10th and final episode, Amy and Danny, after yet another road rage incident, literally drive each other off a cliff. They spend most of the episode somewhere in a natural preserve in Los Angeles, where they are isolated from their smartphones, from the other people in their lives, and from the consequences of the shitstorms they’ve left in their wake. It’s a bold choice to make the season finale a “bottle episode,” but Ali Wong and Steven Yeun’s electric chemistry, which we’ve only seen glimpses of beforehand, makes it work.

Given that there isn’t much for Amy and Danny to do but squabble like children, it isn’t long before they start emotionally unpacking in front of each other. They start by asking each other, “Why are you angry all the time?” Soon after, Danny tells Amy that she is proof of the Eastern brain’s incompatibility with Western therapy, and her simple “no shit” reaction is tacit acknowledgment of the insipidity of her earlier therapy sessions and self-theorizing. When they are with each other, their wounds are exposed and their language distilled down to simple words. Danny asks Amy, “You know what your problem is? You only think of yourself,” and Amy tells Danny, “Your problem is you only bitch about everyone else.” Both sentiments have validity.

But it’s after they accidentally eat psychedelic elderberries that Amy and Danny truly get vulnerable with one another. Danny confesses that the day of the first road rage, he was trying to return the hibachi grills, but the cashier’s refusal felt like the “world wanted [him] gone”—the first we’ve heard him acknowledge his suicide attempts out loud. Meanwhile, Amy confesses, “I don’t want anyone to see who I really am,” and that her American Dream of a nuclear family (husband George and the couple’s daughter June) never really felt like home to her. Amy and Danny, with the aid of psychedelics, finally discover what lies beneath their conscious awareness: a paralyzing existential fear—a void that feels empty but solid, right under the surface. As life passes them by and everything seems to fade away, they are both trying to feel something amid the nothingness.

This existentialism is at the crux of the human experience: we all live in a plane of time that passes us by until we die. It’s a sobering and raw truth that enriches but doesn’t invalidate anything Amy, Danny, or any of the characters in Beef have been thinking, feeling, and experiencing for the past 10 episodes. After all, Beef begins with a public spectacle that arises from two “delusional, fucked-up people” with a kind of all-consuming despair that I haven’t seen in any televisual narratives of recent memory, let alone ones centered on Asian American characters. We may not be able to stop time, or learn about what lies ahead after death, but we can do our best with what we have, being cognizant of ourselves and our emotional baggage while not getting bogged down by history and trauma. As Danny tells Amy on the way out of the tunnel, we have to have faith that “[e]verything’s gonna work out as it should,” especially when we are unsure if it will.

¤

LARB Contributor

Amanda Walujono is an interdisciplinary writer.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Behind Closed Doors: America’s Couple Therapy Entertainment Complex

Every generation gets the iconic couples therapist it deserves.

“Why Are You Pissed!”: On Cathy Park Hong’s “Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning”

Cassie Packard considers “Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning” by Cathy Park Hong.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!