Something Reconstructed: On Pirkko Saisio’s “The Red Book of Farewells”

Niina Pollari reviews Pirkko Saisio’s “The Red Book of Farewells.”

By Niina PollariMay 15, 2023

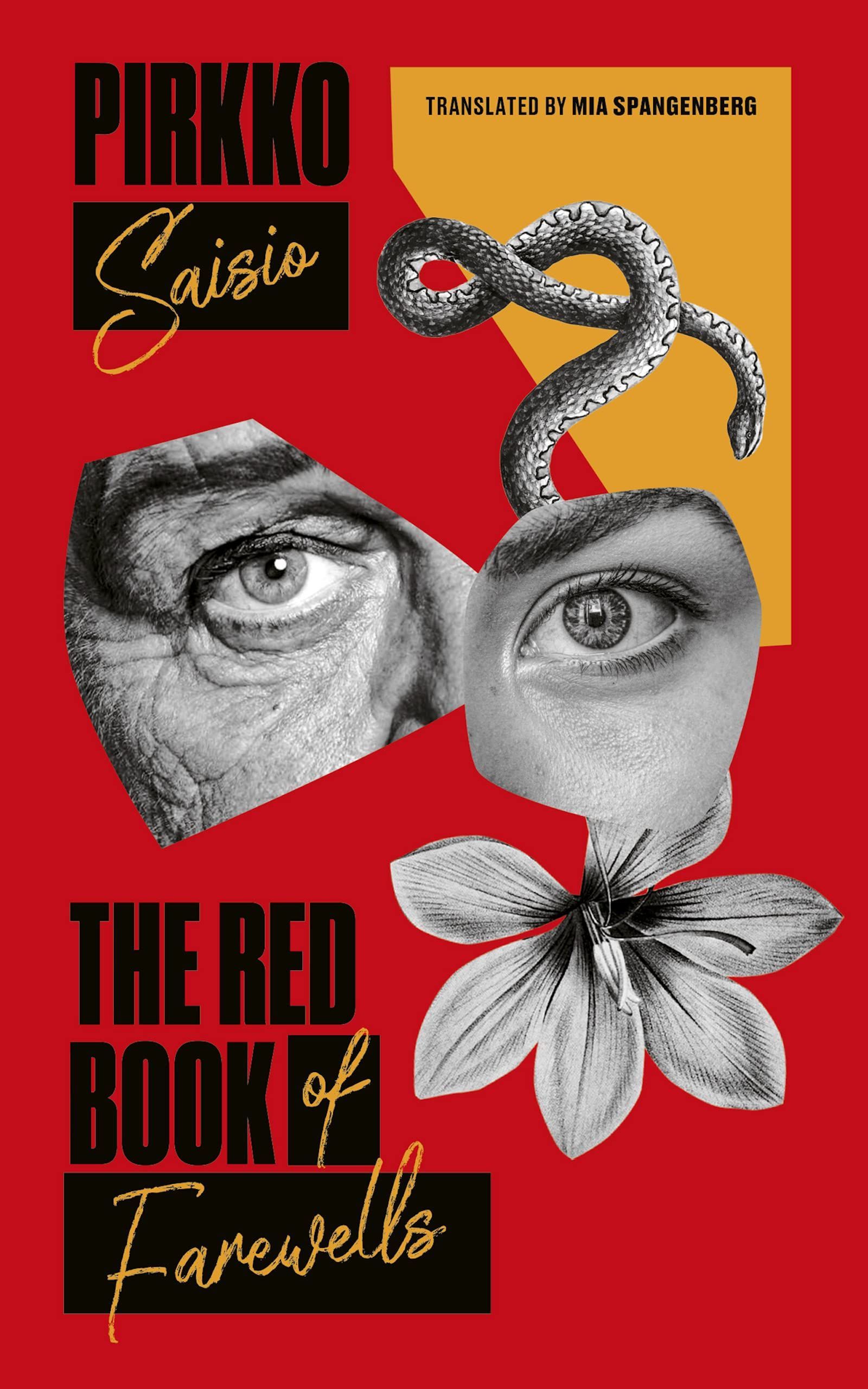

The Red Book of Farewells by Pirkko Saisio. Two Lines Press. 312 pages.

PIRKKO SAISIO’S NOVEL The Red Book of Farewells opens on perhaps the most harrowing loss of all for an author: the complete disappearance of an already finished work. While hiking across an island, the protagonist, also named Pirkko Saisio, receives a phone call from her agent inquiring about the state of a manuscript Pirkko’s supposed to be turning in. “It’s gone,” she says while looking at a dead seal that lies among the rocks before her, its innards exposed, mouthful of yellow teeth open to the air. (For clarity, I will refer to the writer as Saisio and her character as Pirkko.) Her companion vomits. “The whole book?” asks the agent. “It’s all gone, the whole book,” Pirkko confirms. From the start, then, the reader understands that the version of The Red Book of Farewells they’re holding is something reconstructed, rewritten—a reference to an original gone forever.

Though the disappeared manuscript is not mentioned again, the exchange sets the tone for a book about the unreliability of narratives created about a life. The book, like much of Saisio’s work, is about the way that time can change our impressions of the things that happened to us. Memory is like the seal on the shore: decaying over time, eventually nothing but bones. Viewed at any point during its metamorphosis, it would look different—maybe unrecognizable. The opening section ends with Pirkko remarking that she will likely never return to the island.

One of Finland’s most well-regarded contemporary writers, Saisio is the author of over 20 books under her own name as well as several pseudonyms. She has also produced plays, scripts for films, and ballet librettos; she’s acted and directed and seen her work adapted by others. Her oeuvre spans four decades and explores not only the contours of gender, sexuality, and the attitudes of the working class in Finland but also selfhood and the interior experience of the artist. Originally released in 2003 and now translated into English this year by Mia Spangenberg, The Red Book of Farewells, Saisio’s first novel published in the United States, is actually the third installment in a trilogy that also includes Lowest Common Multiple (1998) and The Backlight (2000). Each of the three books jumps back and forth in time between Pirkko’s youth and the present day. Farewells focuses on Pirkko’s discovery of the theater and writing, her involvement with student activism, her awakening as a queer woman, and, eventually, her experience as a mother. It’s also the coming-of-age story of an artist. Young Pirkko’s life is punctuated with reflections that come with experience—the present-day narrator of the book is an older, wiser Pirkko in the late 1990s or early 2000s.

Saisio was born in 1949 into a family of communists in a country that had furiously defended itself against the USSR in two all-encompassing wars not a decade earlier. The constructed Finnish identity is one of grit and independence (see, for example, the untranslatable but quintessentially Finnish quality of sisu, a kind of stubborn bravery in the face of adversity or challenge), so the freedom won in these wars was a source of pride. Nevertheless, there continued to exist a communist faction in the 1940s, of which Saisio’s parents were a notable part. (Her father eventually held a position in the Finland–Soviet Union Society, a postwar organization founded directly after the armistice that ended the Continuation War in 1944 for the purposes of promoting peace and cultural understanding between the two nations.) By the time Saisio was a student, the flourishing radical left enjoyed relative electoral success in mainstream government. It included student organizations like the youth arm of the Finnish People’s Democratic League, a political organization that included the Communist Party of Finland.

The student movements of Saisio’s generation and her parents’ were aligned in their vision of a Finland that could transition peacefully into socialist society free of worker exploitation. But there was a chasm between them with regard to attitudes about sexuality. In the Helsinki where Pirkko dwells in Farewells, the student meetings and theatrical actions are provocative not only for their radical politics but also for the attendees’ audacious presentation at a time when gay activity was still illegal. (Homosexuality was punishable by up to two years in prison until 1971 when it was decriminalized.) In Pirkko’s Helsinki, the personal and political are not collapsed but interlinked, and revolution is closely tied with sensuality. Idealistic young people rush, disguised in drab overcoats, to secret locations where coded knocks allow them inside to discuss the hot political topics of the day. And then, in those back rooms, private identities bloom:

The boy who ran after them isn’t a boy after all, but a girl dressed in a polyester suit and tie; her hair is cut short in the back and she’s wearing a gold signet ring on her little finger.

She sits on the old bus seat with her legs spread wide.

Pirkko finds these locations, with their glamor and sexual openness, to be a “secret home, a criminal home,” even while she notes the difference between her attraction to the personal and the political: “The thirst of her parched pores and the secret, criminal games of the green room are hazy, private, and shameful compared to the clear-cut arguments for communism.” The allure of breaking the law is tied to a sense of self-discovery, and Pirkko later describes a sense of loss when decriminalization does come: “No more secret messages; no more golden signet rings slipped on little fingers; no more gossamer-thin golden rings hanging from people’s left earlobes.” The loss of the clandestine is a minor crisis to Pirkko. If not a criminal, what is she? There needs to be something more.

This is where individual relationships become important. Pirkko’s first girlfriend, the clown-eyed girl (a moniker assigned because of her bold eyeliner), comes to Pirkko’s home with a bunch of out-of-season flowers that rouse the suspicion of Pirkko’s mother, who considers same-sex relationships to be a kind of mental illness. But when Pirkko’s parents are away, she and the girl play in the family apartment: “The clown-eyed girl puts on one of Father’s suits and paints on a mustache and a mole on her cheek with an eyebrow pencil; she smokes Father’s pipe, the smoky haze giving cover to their lovemaking.” This cabaret is simultaneously child’s play and foreplay, conflating the overlap of home and identity.

But this kind of playful, fluid freedom can only happen when the mother isn’t there: the presence of the mother is a reminder of the painful disconnect between generations who share a political identity but not a personal one. There’s a short, brutal exchange: “I no longer have a daughter,” the mother says. “So, I don’t have a mother, is that it?” replies Pirkko. As Pirkko leaves, her mother hands her a bag of underwear and socks she purchased for her, avoiding her daughter’s hand. It’s like a final gesture tracing the point at which maternal responsibility ends: she will acknowledge practical needs, and nothing more. Years into the future, Pirkko is still mourning their estrangement.

The other deep personal footprint in the book belongs to Havva, Pirkko’s great love. By the time they meet, Pirkko has entered theater school. Havva is also in the program, beloved and magnetic, thriving on attention from everyone: “Havva’s mouth is big and sensuous, slightly soft. Her mouth wants a lot.” Pirkko falls for her, and there are fragments of a hurtling romance; they move in together. But Havva is capricious and unreliable. Early in the book, there’s a skip in time that shows the reader that there’s now a baby, referred to in the book as Sunday’s Child for the day of the week on which she is born. Havva is also nowhere to be found during the birth. When later Havva does appear, she and Pirkko gaze together at the baby through the window of the hospital nursery:

“Isn’t she beautiful?”

“Yes,” Havva says, wistfully, absently.

She can’t understand Havva’s frame of mind.

It’s as if Havva is looking past Sunday’s Child to other babies[.]

Later, it becomes painfully clear that Havva has been with other people at this pivotal moment, that Pirkko has not been a priority for her.

As I write this review, I am newly postpartum; Havva’s insistence on keeping her options open at a time when profound, committed partnership is so vital struck me as a particularly deep form of betrayal. With one eye on the exit, Havva is the archetypal lover you desperately want but can never fully possess, the one you expend all your resources trying to keep, even as they yank their hand out of yours and walk away (the sound of Havva’s fast footsteps is described several times over). Details of emotional betrayals arrive one at a time, interwoven into the past and the present, and we watch Pirkko’s emotional stability erode as she grapples with single motherhood and with the widening gyre of depression that follows Havva’s eventual—and total—absence. Then there is the familiar push-pull when someone incredibly charismatic tries to come back after being gone for so long: Havva, after being unreachable for weeks, returns with donuts, an incredibly mundane gift meant to understate the significance of her own absence.

Pirkko’s other loves are continuously present: there’s Honksu, the reliable later-in-life partner with whom Pirkko builds a stable existence (she is the vomiter on the seal island at the start of the book). Even the clown-eyed girl makes an appearance in the present day (she has become a nun, and they share a brief, amicable exchange). But Havva remains a mystery, her story told entirely from Pirkko’s anguished point of view. By the time Sunday’s Child is grown at end of the book, we don’t even know how much she knows about Havva—and it might be better to know less.

Long an object of study in Finland, Saisio’s work is beginning to gain more global recognition now, cementing her place in the canon of autofiction that also includes the Nordic writers Karl Ove Knausgård and Tove Ditlevsen. But in addition to working in the autofictional space that blurs the line between diary and art, The Red Book of Farewells and its two companion books make surprising formal moves, too. In addition to the jumps in time and the not-infrequent interruptions of the narrator to contradict unfolding events, the book’s untraditional structures also include negative space, and interwoven onto the page there are numerous line breaks reminiscent of verse:

Memory is no fairy godmother.

Memory is a mercurial prince.

He keeps the real jewels for himself and throws imitations to his subjects.

I read these poetically at first, as a poet myself; to me, they function to add breaths into the text, pacing it for the reader. But one can also hear them out loud as dialogue: this way, their pauses hang in the air, creating expectation for the audience. Saisio came up in the world of theater; it was her first foray into the arts, and she has continued her involvement with playwriting and performance throughout her career. But her realization that she is a writer is a key development in this book. And there’s a patron saint to this realization: though Saisio’s attitude toward authorship is distinctly Barthesian in that she believes equating narrator with author imposes an unnecessary limit onto the text, the book’s guardian angel is Bertolt Brecht. “Bert” shows up several times in the text, always offering benevolent narratorial advice. At one point, Pirkko is in the hospital with an infection, and in comes Brecht, telling her to “rise, get out of bed and walk, and stop her senseless sniveling.” He smiles a “broad, brazen smile” and encourages her to keep a small notebook of observations. Pirkko writes the opening lines of her first novel essentially at his behest in the hospital.

Farewells is fundamentally a book about writing. It’s unique in structure and voice, with Saisio constantly reminding the reader of the disconnect between the character and writer. The writer interjects constantly, sometimes even calling out a misattributed quote, and then refusing to correct it, preferring to keep the flow of the story: “I’m invoking my privilege as an author to put this sentence into the mouth of the person and in the situation where I think it best fits.” Love, class, political and sexual identity—these may be the topics of memoir. But Pirkko Saisio once remarked that she would never produce a traditional memoir, that “everyone always has a reason or need to tell things the way they’re told.” In The Red Book of Farewells, she tells it her way while also reminding the reader of the pitfalls of believing everything a narrator has to say.

¤

LARB Contributor

Niina Pollari is a writer and translator and the author of the poetry collections Path of Totality (Soft Skull, 2022) and Dead Horse (Birds, LLC, 2015).

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Universe’s Couch: A Conversation Between Bud Smith and Mike Jeffrey

Bud Smith and Mike Jeffrey discuss their semi-autobiographical fiction in the forthcoming “Fire” issue of “The LA RB Quarterly.”

It Girls and E-girls: On Madeline Cash’s “Earth Angel”

Anna Dorn reviews Madeline Cash’s “Earth Angel.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!