It Girls and E-girls: On Madeline Cash’s “Earth Angel”

Anna Dorn reviews Madeline Cash’s “Earth Angel.”

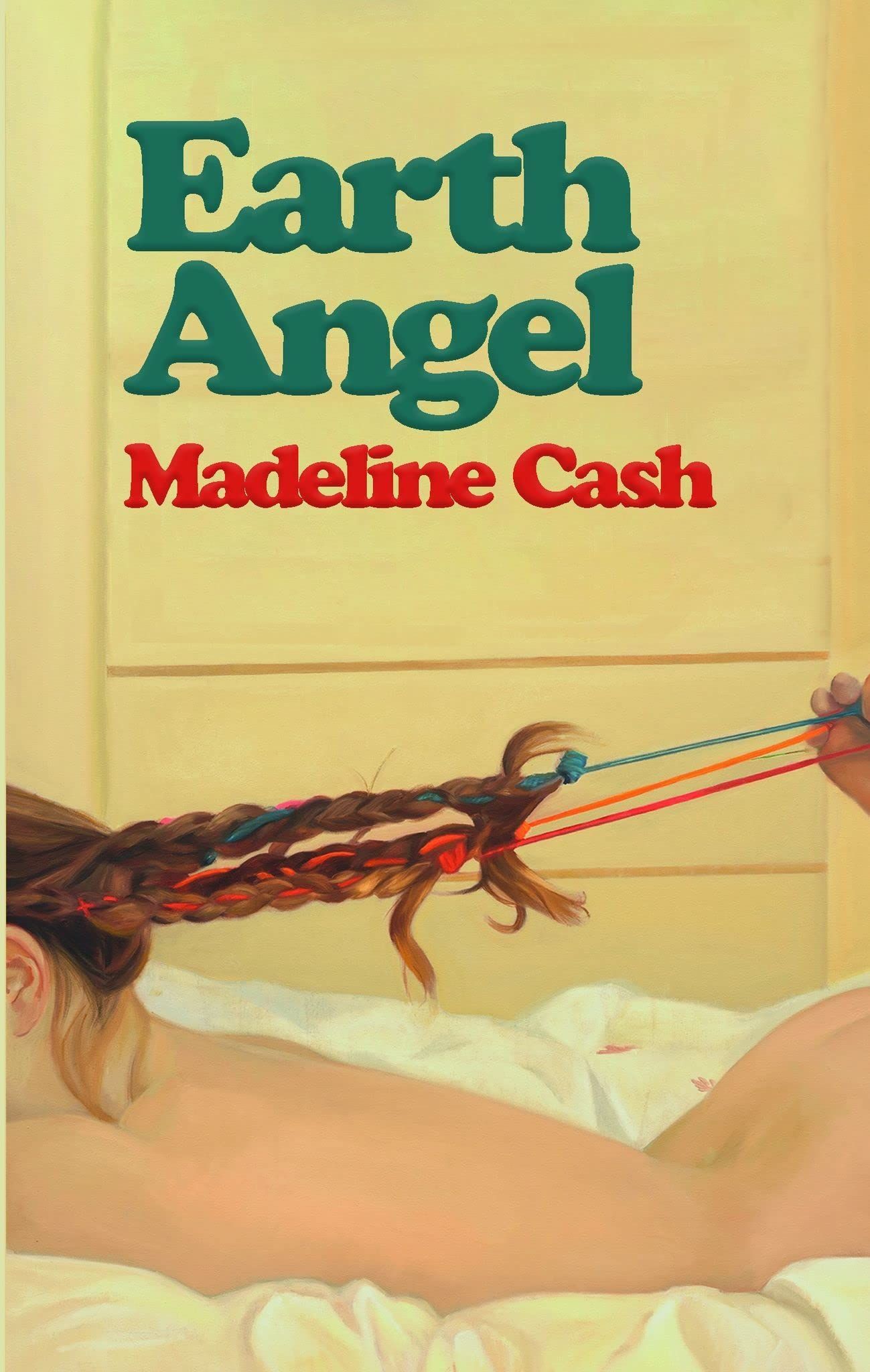

Earth Angel by Madeline Cash. Clash Books. 160 pages.

“I’M A LUTHERAN and an American and a hostage, perennially updating like a smartphone, barreling forward into the profound depths of the universe.” If there is a thesis of Madeline Cash’s debut story collection, Earth Angel (2023), it’s this line at the end of the collection’s fifth story. The statement captures the allure of Cash’s writing—cheeky and very online in the manner of a twentysomething, but more mature than you would expect. The stories in Earth Angel do, in fact, barrel toward the profound. But first and foremost—they’re very fucking fun.

In a dark way.

“Plagues” is a biblical story in which the frogs develop seasonal depression. In “Beauty Queen,” God tells a girl to win the Teen Miss Florida pageant. A marketing agent in “Jester’s Privilege” is tasked with promoting “Islamic fundamentalism with a new flair.” Later, a friend tells her how cool it is “that you got that terrorism organization to participate in affirmative action or whatever.” There is an uncanny valley element to these stories. Just as a figure that is almost but not totally human will inspire more discomfort than a figure that is more clearly artificial, Cash’s stories evoke unease because they aren’t pure parody.

The facetious surrealism continues throughout. In “Slumber Party,” a woman hires actors to play her friends for her 30th birthday. The scheduled itinerary involves group sex with the actors, in which one actor says he can tell her star sign by the texture of her cervical mucus. “They Ate the Children First” follows a woman “about to turn [REDACTED]” who embarks on a dangerous journey to buy a dopamine enhancer that causes users to hear angels singing. Before that, she Googles things that bond people: “Google said trauma.”

Cash is funny and ironic in the way those of us who grew up in the wake of 9/11 had no choice but to be: tongue-in-cheek references to terrorism appear throughout Earth Angel. Reading, I recalled the very first scene of Euphoria (2019– ), in which the main character, Rue, is born while the World Trade Center attacks play on the hospital television. Where Rue turns to drugs, Cash turns to dark humor (and maybe also drugs). In the title story, protagonist Anika’s brother says, “Osama Bin Laden was gay.” In the story “TGIF,” a character is “falling in love with an ISIS recruiter online.” Throughout the collection, Cash grants levity to nearly every dark subject haunting twentysomethings. “Your rapist is on Instagram,” she writes, “hanging out with everyone.”

I had Cash confirm over email that she was born in 1996—the first year of Generation Z births. I’ve been wondering for a few years where the Gen Z authors are. The oldest members of the generation are 27, which is young to publish a book, but Sally Rooney was 26 when she published Conversations with Friends in 2017; Bret Easton Ellis published Less than Zero (1985) when he was 21. A voice of Gen X, Ellis chronicled anesthetized teens partying and fucking in Los Angeles, leading critics to call Less than Zero the first “MTV novel.” Rooney gave us a paradigmatic millennial novel: a self-loathing high achiever who identifies as a Marxist but lives luxuriously, a disconnected wunderkind caught in a torrid affair.

Raised in Southern California, Cash is more Ellis than Rooney. Some of her long and hurried and affectless sentences recall the literary Brat Pack founder:

I roll up my uniform skirt to make it shorter and get detention and I practice cello in detention which makes me hate the cello and I probably could have been a first chair concert cellist had they just let me wear my skirt above the knee like an American but now I forever associate cello with punishment and rejection and stop playing and start stealing cigarettes from my mom’s friend Lisa’s purse and sneaking out of my bedroom window at night to huff computer cleaner with boys and my mind is clean but the computer is filthy.

As with Less than Zero, Southern California is a main character in Earth Angel. “It’s 102 degrees in Los Angeles and my mom is picking me up from the mall security office for shoplifting from Victoria’s Secret,” the main character announces in the same story. In another, the protagonist is from Palos Verdes, a rocky peninsula south of Los Angeles, like Cash herself. The narrator explains, “Verdes is Spanish—the language the gardeners spoke—for green—the color they kept the lawns.”

A theme of godlessness, or of a disappearing God, also runs through the collection. Like the protagonist quoted in the first sentence of this review, Cash was raised Lutheran. She “went to church every Sunday [and] was communed and confirmed.” The first paragraph of the collection announces, “God was punishing us but we were happy because at least we knew that God existed.” But over the course of the collection, God’s existence becomes less certain. An actor in “Slumber Party” tells the protagonist during gossip hour “that God is dead.” In another story, the first-person protagonist turns 24 and announces that “there is no God.” Another story begins, “I heard some girls say that God was absent from our town.” In yet another, characters sleep in pews of a Catholic church whose altar has been tagged with spray paint to read: “THERE IS NO GOD.” The collection ends with a photo of a black hole.

Perhaps inspired by our godless culture, or maybe by Catholicism’s trendy resurgence among downtown It girls and e-girls, Cash founded the quickly cult literary magazine Forever, whose landing page contains a pop-up that asks, “Are you Going to Heaven?” The relatively new magazine has published writing by Sheila Heti, Kate Zambreno, and Eileen Myles. Some say Forever took over where alt-lit magazine NY Tyrant left off. Cash told Interview that to recruit writers for Forever, she would go to Tyrant’s website and email authors they’d published years ago. Forever co-founder Anika Levy said that, like Tyrant, Forever favors “style over plot.” In the spirit of alt-lit, Earth Angel ends on a story called “Autofiction”—named for the hybrid genre favored by alt-lit king Tao Lin (who blurbed Earth Angel)—which contains a list of people who appear in the book, including Madeline and Anika. But where the early alt-lit emerged from a nihilistic coastal elite, Forever feels more optimistic, or at the very least it strives to be.

Anika appears in several stories throughout the collection. In the title story, her shitty but powerful boyfriend says to her: “I’m lucky to have you. You’re my rock. You’re my earth angel.” In the manner of a Cash protagonist, I google: What does it mean to be an earth angel? Google, via AP News, says that earth angels are “highly evolved spiritual beings” who are “commonly known as light workers” and whose “goal in life is to be happy.” I might argue that despite its dark subject matter—rape, terrorism—this is the goal of Earth Angel as well: to be happy.

In a recent interview with the Forever girls, Levy describes walking outside and Cash looking up, “really bright-eyed” and saying, “It’s snowing!” Cash paused, reassessing. “Or no, I’m sorry. It’s probably ash from a tenement fire.” Levy told Nylon: “I feel like that’s exactly what our worldview is: wanting to be really wide-eyed, but also embracing the utter cultural, institutional, and material decay.”

Earth Angel reiterates this sentiment: life is a hot mess, but we try to be happy. It’s a fleeting happiness, ephemeral because something shitty will happen again—you’ll see your rapist smiling on Instagram or be asked to do marketing copy for a terrorist organization—and you ultimately can’t escape the great unknown, the black hole at the end of this book and everything else.

If there is a second thesis for Earth Angel, it would be this line: “The trees are suicidal and it doesn’t matter what language the shower is in, you never feel clean anyway.” Uncanny, poetic, and bleakly funny, Earth Angel reaches for a higher power in a society that has forgotten how to believe.

¤

LARB Contributor

Anna Dorn is an author and editor living in Los Angeles. Follow her on Twitter @___adorn.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Alone Together: On Annie Ernaux’s “Look at the Lights, My Love”

Apoorva Tadepalli reviews Annie Ernaux’s “Look at the Lights, My Love.”

Random House: Surviving Rejection (After Rejection)

Anna Dorn explores a career in rejection (and eventual success).

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!