I Sing the Body Prosthetic: On Mario Bellatin’s "Mishima’s Illustrated Biography"

Mario Bellatin’s reality-bending novellas offer a poignant commentary on everything from sexual orientation to the multiplicity of the self.

By Jeffrey ZuckermanMarch 23, 2014

ACCORDING TO MOST reliable sources, from Mainichi Shimbun and The New York Times to eyewitnesses in the room where it happened, the famous Japanese author Yukio Mishima committed seppuku and subsequently died.

The Mexican author Mario Bellatin disagrees. In Mishima’s Illustrated Biography — recently translated from Spanish by Kolin Jordan along with his earlier novella Flowers — Bellatin describes the famous author as having survived the ritual suicide. That act becomes a strange footnote in this fictional Mishima’s history; aside from his lack of a head, he is virtually unchanged. He goes on publishing books, giving lectures, traveling around the globe to receive awards and honors.

This version of Mishima seems to be compos mentis, even if not entirely compos corporis. It is nigh impossible to wrap our heads around this man who is simply missing a head. Even Kolin Jordan himself, the faultless translator of the text, confessed as much. He translated a section where Mishima, having been given a guest room in which to sleep during a trip, wakes up to screams because the room’s owner has returned early and found a headless man sleeping in her bed. Typing the English translation, Jordan found himself “laughing out loud, having forgotten that our hero was headless!”

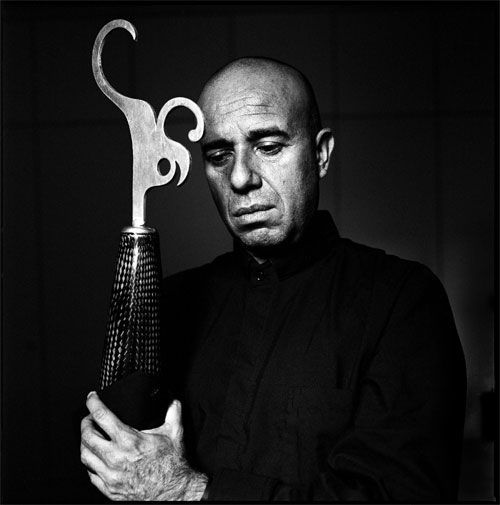

This strange case of a beheaded writer is hardly the oddest part of Mario Bellatin’s work. Just trying to characterize Bellatin proves a challenge. He is a Latin American hybrid: born in Mexico in 1960, he spent some of his youth in his parents’ homeland of Peru and studied film in Cuba. He founded the Mexican Dynamic Writers’ School, which espouses such strategies as not writing for weeks on end, and converted to Sufism. A description of his body, in fact, gives a better idea of the mind behind nearly 20 novellas: a finely tanned man with a carefully shaven head and a soft-spoken voice that belies his formidable presence. He is often photographed wearing loose button-down shirts or black tunics, with one sleeve pulled over his left arm. In those photographs, the other sleeve hangs from the part of his right arm that isn’t there.

In Flowers, Bellatin tells the story of the experimental drug Thalidomide, which was prescribed in the 1960s and 1970s to pregnant women to alleviate depression and nausea. Over the coming years, it quickly became evident that the drug caused birth defects, specifically deformed or missing limbs — a story the real-life Mario Bellatin shares. Today, he augments the stump on his right side with numerous prostheses, ranging from the mundane (such as pincers) to the bizarre (a large implement that recalls both a bottle-cap opener and a French curve) and the risqué (a silver dildo, notoriously worn during a literary conference).

Flowers & Mishima's Illustrated Biography

by Mario Bellatin

7Vientos Press

This missing part of his body finds its analogue in nearly all of his published work, from the writer in Flowers, who is missing his right leg, and the mysterious protagonist of Hero Dogs, who has no arms or legs, to the unexpected appearance of Bellatin’s identically-named and featured alter ego in Black Ball — and, of course, the headless hero of Mishima’s Illustrated Biography. Even an abnormally large nose suffices for bodily deformity and writing material. The New York Times reported that while at a literary conference, Bellatin and other authors were asked to discuss their favorite writers. “Unwilling to make a choice, he invented a Japanese author named Shiki Nagaoka and spoke with apparent conviction about […] Nagaoka, who was said to have a nose so immense that it impeded his ability to eat.” Somehow, the audience bought it and begged Bellatin for more details — enough that Bellatin spun this odd moment out into a novella (titled, unsurprisingly, Shiki Nagaoka: A Nose for Fiction). The caption is a reference to Shiki Nagaoka’s nose, damaged intentionally “for the purpose of avoiding that the author be considered a fictional character.” Because the nose itself has been scrubbed out, there is all the more reason to doubt that this Japanese writer ever could have existed — that this eponymous nose was not simply concocted for fiction. That nose, as much a physical oddity as any of the other characters’ missing appendages, seems too perfectly a transmutation of Bellatin’s identity into his work.

Any attempt to link Bellatin’s books to his identity includes the question of sexuality. When a reader asked him in 2012 about having declared himself gay and also having had a girlfriend who happened to be a Catalan novelist, Bellatin responded: “I think we are past the point of making such distinctions or declarations […] each of us is God knows what.” It comes as little surprise, then, that many of his characters exhibit atypical sexual preferences and orientations; one of his characters in Flowers is nicknamed the Autumnal Lover because of his love for the elderly, while Beauty Salon, his most famous book, is narrated by a gay salon owner who has two male transvestite coworkers. As a mysterious epidemic ravages his city’s population, he turns the salon into “the Terminal”: a hospice or nursing home for victims of this unnamed plague who know they cannot be saved. Upon Beauty Salon’s publication, in Spanish and in English, many critics read into both the narrator’s and the author’s backgrounds and interpreted the spare story as an allegory for the AIDS crisis.

Beauty Salon, although unusual within Bellatin’s oeuvre, is the best place to start reading Bellatin’s work. It is about the same length as all his other books so far translated into English —63 small pages — and equally as elliptical and reticent in parceling out information to its readers. But it is a wholly self-contained story, with a clear beginning and end; the world it describes is understandable in its forces and its trajectory. I read it in a single sitting, and momentarily mistook the bare walls of the room where I sat for those of the Terminal where sufferers rotted and breathed. I thought for a moment, before coming back to reality, that if I looked outside I would see the pond behind the Terminal, where the narrator throws out many things he no longer needs, and the shack where his former coworkers died.

As Adam Morris explains in his essay on Bellatin, "Micrometanarratives and the Politics of the Possible," Beauty Salon is, in a sense, a “first-order” book that presumes no antecedents. Only a couple of Mario Bellatin’s other books translated into English so far — including Hero Dogs, found within the collection Chinese Checkers, and Shiki Nagaoka: A Nose for Fiction — offer their readers the same luxury. All of Bellatin’s books are all strangely interconnected, both to each other and the rest of the world. His universe is a rhizomatic and nonlinear one, defined by the strange and unexpected interconnections between his own life and his various stories, and even those of other writers.

Flowers, for example, is the other of Bellatin’s most famous titles in the hispanophone world. The winner of Mexico’s Xavier Villaurrutia Award, it announces its ambitions and its intertextuality in its preface:

There is an ancient Sumerian technique […] It allows for the construction of complicated narrative structures based upon the sum of certain objects that together form a whole. It’s in this way that I’ve tried to relate this tale; structured a bit like the epic poem of Gilgamesh. The idea is that every chapter can be read separately, as if it dealt with the contemplation of a flower.

What follows is a surprisingly fragmentary text that hops from moment to moment, and reaches out beyond the novella itself. There are several main threads to the narrative, and different sections center on different moments: a doctor and his assistant interviewing purported Thalidomide victims to determine whether they are eligible for compensation by the drug’s manufacturer; a writer with a stone-studded prosthetic seeking some sort of religious transcendence; his acquaintance the Autumnal Lover, who slowly grows close to the elderly people with whom he wishes to have sex; a husband and wife who divorce and watch their lives spiral out of control as the husband cannot afford child payments and the mother raises the child on her own; and three beauticians who come from out of town to spend an evening at a nightclub. It’s easy to wonder if those three women are supposed to echo the three male beauticians from Beauty Salon, although no concrete evidence is ever given. And, later, the text unexpectedly references “the story of the transparent bird’s gaze […] written by Mario Bellatin” — another novella that Bellatin indeed has already written.

All these references and vaguely connected narratives have the strange effect of making Flowers an even more dreamlike text. Its full interpretation remains agonizingly out of reach. The 35 sections, each prefaced with the name of a flower, sometimes refer to the flower in question, and sometimes not. The book as a whole explicitly contemplates many different themes — bodily deformations, atypical or failed families, varieties of love, theatrical spectacle, science as a religion failed by its practitioners — but only fleetingly mentions flowers throughout. It is as if Bellatin decided to write down his own contemplations and considerations, which we happen to have the luxury of reading if we so wish. But Bellatin’s writing is too striking and cohesive to reduce to mere musings. As more and more of his books have been translated, the strangeness and interconnectedness of his work has come to light.

Bellatin’s extraordinary use of intertextuality and metatextuality draws attention to itself; it is as if his stories were as incomplete as his own body, as his alter egos walking around in his fictional worlds. In Bellatin’s “first-order” narratives, the prostheses are somewhat literal. The protagonist of Hero Dogs missing all four limbs uses his dogs and the people around him as his prostheses. In Beauty Salon, the narrator himself is a prosthesis to these victims incapacitated by plague; the story ends when he himself can no longer serve (or narrate) his purpose. In Flowers, many of the Thalidomide victims (and mutants hoping for equal restitution) use money or actual prostheses to complete themselves.

And in Mishima’s Illustrated Biography, something must serve as a prosthesis for Mishima’s missing head. He lives in the world of Flowers’s victims, but cannot follow the same path that those victims do; in fact, he claims that he lost his head because of Thalidomide exposure in utero and attempts to fly to Germany to receive compensation for it. He is rebuffed because anybody can see the exposed muscle and bone of his sliced-off neck, and ascertain that no drugs caused this loss. So if the drug company cannot redress his missing head, what can?

Mario Bellatin’s head, actually. If this sounds suspiciously like an assertion that Bellatin is replacing Mishima, it would not be entirely unfounded. This replacement or displacement is one of the most shocking elements of Mishima’s Illustrated Biography. Two extraordinary scenes of authorial displacement dominate the novella’s 56 pages: a lecture and a play.

During the lecture about Mishima that takes up the present moment of the novel’s arc (which is frequently obscured by Mishima’s own thoughts and memories), the narrator, a member of the lecture audience, is shown a projection from a “teaching machine” that includes several of Mishima’s books. But they are not cover images for The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea or The Sound of Waves. Instead, “we regarded the covers of Chinese Checkers, Beauty Salon, and Mrs. Murakami’s Garden.” The first time I read these words, I suspected it was simply a joke on Bellatin’s part — one step beyond the author-as-fictional-character tricks of Michel Houellebecq in The Map and the Territory or Michael Martone in Michael Martone by Michael Martone. So Bellatin decided to slip in his own books under Mishima’s own name — what of it?

But then came the other moment of shock: “[Mishima] remembered very clearly when they staged a play based on his book Beauty Salon […] What was happening onstage shone brighter than anything that happened in daily life.” The idea of bringing one of Bellatin’s own novels to life by using actors within another novel is a particularly inspired one, but as I read it I felt like a trapdoor was opening beneath me, and I was falling.

Did I fall? Or did my mind fall? One of those happened, and I hadn’t yet come to the most shocking part, the moment when I knew that the line dividing fiction from reality had been violently severed:

When the play based on Beauty Salon was over, and perhaps keeping with the prophetic nature he was sure was contained within the text, he ran backstage and was overcome by the sight of his own character. He later took him home. A painful experience ensued, both for Mishima and the actor. The process that finally allowed the actor to strip himself of the character was a slow one. Mishima thought with horror on the whole situation. Before finishing, just when the actor was at the point of fleeing, the character injected the aches, the sickness into Mishima’s body, which, curiously, was the theme of the play that had just been performed. That was how Mishima came to be contaminated, by his own book, with an incurable malaise.

Immediately before this episode, Mishima wonders to himself about Beauty Salon, “What kind of fear is capable of generating writing like this?”

Fear — somehow that emotion had never occurred to me. What kind of fear was driving this strange sequence of books? The answer came as I asked Bellatin by email: “Do you think of yourself as one self, or as many selves?”

He answered my question with another question: “Is any of us just one self? Much of what I try to do in my writing is to eliminate time and space — what's left besides the self?” As those elements are stripped away from his diverse works, what slowly results is a single universe containing the worlds of all his inventions. It might simply be classified as Mario Bellatin’s universe — one that appears to be parallel to mainstream literature, or even, perhaps, a willful misreading of mainstream literature.

In the final part of Mishima’s Illustrated Biography, Bellatin recalls Kafka through a character called the “man-poem.” This character, from a friend’s story, bears wounds on his back much like the ones inflicted by the machine from “In the Penal Colony”:

When he turned around, the man-poem’s back was gray and covered in symbols. They looked like small wounds caused by a needle. Mishima said [to his listeners that] he wasn’t able to decipher the meaning at that time. All he could do was fall to his knees and lick the droplets of blood falling from the newest symbols on his lower back. With his back still turned the man-poem said that, in a way, the symbols told Mishima’s story up to the time of his assisted suicide. Mishima told him he didn’t care to know, not now and not then, anything about what happened on that occasion, when his head was separated from his body with one swift slash.

In Kafka’s story, the notorious machine was designed to pierce an accused man’s back with thousands of needles to write in blood the law he had broken. But here Bellatin is destroying the rules of authorship, and using the not-so-raw materials of finished art to create new artworks of his own, drawing energy from his forebears like Mishima licking the man-poem’s blood.

As Mishima’s Illustrated Biography draws to its close, it takes an even more puzzling turn away from the typical conventions of narrative, towards wholesale disappearance. The man-poem is a transformed lumberjack’s son who turned gray and bloody at the moment he was supposed to say “amen” for his family’s supper. Through this transformation, the lumberjack’s son disappears from his own life while the man-poem enters it. Similarly, Mishima and the machine used for the lecture about him disappear a few pages later: “The impeccable Japanese professor ended his intervention that evening by affirming that Mishima never really existed. Neither did the teaching machine he had invented, by means of which we had been watching a kind of reflected reality.” If this is supposed to be a parallel transformation, what replaces the vanished Mishima? Is this a sly wink telling us that the headless Mishima in the audience is entirely Bellatin’s own invention? I could not decide on a satisfactory answer. And I was reminded of Bellatin’s answer to my question: “what's left besides the self? To tell the truth, I'd like to eliminate that as well — that's something I'm working on.”

Erasures and displacements and replacements — these are the themes that ground Mario Bellatin’s recurrent focus on deformed bodies and intertextual machinations. If, as the professor asserts before leaving, “the figure of Mishima should remain always situated just beyond the reach of any gadget or apparatus,” then even the most finely calibrated intellect has to come face-to-face with the infinite, black abyss of Bellatin’s imagination. Aristotle’s unities of time and place have long since been destroyed; Bellatin’s brilliance, in his desire to eliminate himself, is to destroy the unity of the author. He has taken in the entire universe and used its materials as a prosthesis wherever he wishes to supplant his own work. The result, emblematized in Flowers and Mishima’s Illustrated Biography, is a deconstruction that removes himself from the center of his work. As the line between truth and fiction, life and art, grows increasingly blurred, it comes as no surprise to find Mario Bellatin standing at this divide, dancing in the gray zone.

¤

Jeffrey Zuckerman is digital editor of Music & Literature magazine.

LARB Contributor

Jeffrey Zuckerman is digital editor of Music & Literature magazine. His writing and translations have appeared in the Yale Daily News Magazine, Best European Fiction, The White Review, 3:AM Magazine, and The Quarterly Conversation. In his free time, he does not listen to music.

LARB Staff Recommendations

All the Rage in Denmark: Yahya Hassan and the Danish Integration Debate

Teen poet sensation Yahya Hassan is turning the Muslim immigrant community in Denmark upside down.

Around the World: Russia, Denmark, Argentina, Mexico

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!