Seeing the President Naked: On Curtis Sittenfeld’s “Rodham”

What if Hillary never married Bill? What if she was elected president?

By Emily AdrianMay 19, 2020

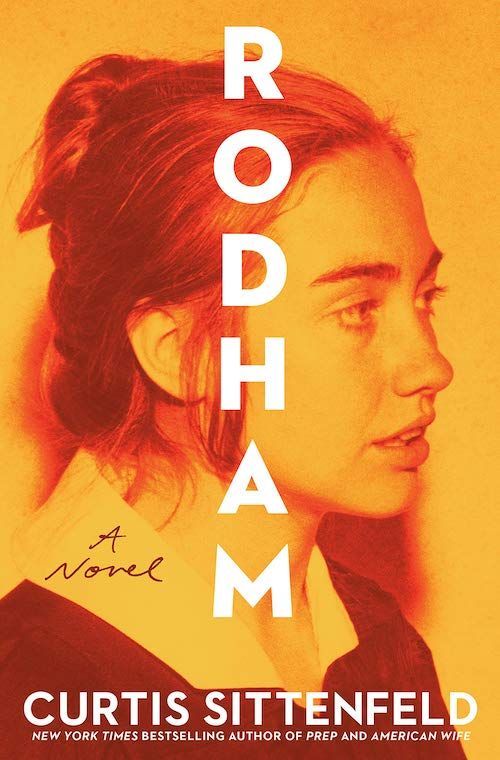

Rodham by Curtis Sittenfeld. Random House. 432 pages.

WHEN I WAS A CHILD, I asked my mother if the president of the United States wore pajamas to bed or if he, like my father, slept in his underwear. My mother speculated that Bill Clinton slept in his underwear. This seemed unlikely to me: Wasn’t the president supposed to be more formal? And what if staff members barged into his room during a late-night crisis?

In her new novel Rodham, Curtis Sittenfeld strips our political elites naked. The book takes the form of a counterfactual political drama: Bill and Hillary split up in their 20s and never married. Rodham is the second book Sittenfeld has written about American politics; her 2008 novel American Wife explored the imagined interiority of a barely disguised Laura Bush. You may wonder why one of our most talented novelists would return to this genre. What you should ask yourself is why you want to see our country’s leaders absent their coached smiles, rehearsed talking points, and unnatural face paint. Because you do.

The opening chapters of Rodham, which detail Hillary’s graduation from Wellesley College, her years at Yale Law School, and her courtship with classmate Bill Clinton, feel a little icky. Through the young Hillary’s eyes, we are subjected to Bill as a smooth-talking, lionish lothario. Meanwhile, Hillary’s ambition to be ambitious is not particularly inspiring. A friend with whom I shared my galley copy said that she felt like she was reading fan fiction about the Clintons. Erotic fan fiction: Bill compliments Hillary’s “nice soft bum” and “delicious honey pot.” Sittenfeld has a knack for describing intercourse in a way that makes a person never want to have it again. Days after finishing Rodham, I am haunted by the description of Bill’s “erection inside me and his scrotum bumping against the lower part of my bottom.”

But Sittenfeld assures us that we are not reading fan fiction; we are not even reading a romance. Before taking an exam, Hillary finds in her bag a note from her boyfriend: “I cherish you.” And from a distant, husbandless future, our narrator wonders, “Did I imagine that my life would be full of such emotional extravagance? I must have, because to save the note did not occur to me.” The line is classic Sittenfeld. It signals that she is in complete control of the story, that she has precisely traced the arc of her protagonist’s life. Marriage is not in the cards.

Rodham mixes what might have been with what was. Many characters — Bill, Hillary, Obama, and Trump — keep their names, even as Sittenfeld assigns them fictional lives. While Bill holds the office of governor of Arkansas in the book, as he did in real life, here he goes on to become a skeevy tech titan, filthy rich in the sense that he has a lot of money and in the sense that he spends much of it on silencing the women he has assaulted. Occasionally, a moment from history — such as Anita Hill’s testimony and the subsequent confirmation of Clarence Thomas — is presented straight, almost journalistically, complete with a quote from Hill’s opening statement. Though Rodham could be classified as political fantasy, Sittenfeld is writing about America, about the unseemly circus of our democracy, as it really is.

The promise of Rodham is to show us a powerful woman without her armor — to reveal the desires, doubts, idiosyncrasies, and failures that make her human, and which she has necessarily kept hidden. In the year 2020, we expect so little from our male leaders that electing our next president will mean choosing between two alleged rapists. Of course, we know there is a double standard. We would never allow a woman who has been credibly accused of assault to become president. If we did elect a woman, and if she were to repurpose the Oval Office as oral sex headquarters (no pun intended), neither Republicans nor Democrats would dismiss the scandal as Madam President’s private business. Exactly how much do we demand of ambitious women? Rodham raises the question: How messy is Hillary allowed to be, and how messy is she actually?

Sittenfeld is not afraid of the possibility that her protagonist is objectionable. The author imagines Hillary running for the Senate in the early ’90s, knowing that her campaign will eclipse Carol Moseley Braun’s, who might otherwise become the first African-American female senator. (Over the phone, Hillary assures a black friend: “This isn’t about race.”) Sittenfeld also illustrates the process through which Hillary convinces herself that the end (becoming president) justifies the means (accepting the endorsement of Donald Trump — who, in this parallel universe, is no less racist, sexist, or unhinged than he is in ours). Throughout the novel, Hillary oscillates between condemning Bill as an irredeemable sexual predator and believing he is the only man who can satisfy her intellectually and sexually. Her inconsistency is relatable: we like to categorize ex-lovers as bad or good, while reserving the right to change our minds. Hillary’s wavering impression of Bill also evokes our tendency to cast presidential candidates as either devils or saviors, as the embodiment of inequality and corruption, or of hope and progress.

In Rodham, one incident nearly costs Hillary the presidency: a former staffer accuses her of sexual harassment. Decades earlier, during Hillary’s 1992 Senate campaign, her communications director ordered his deputy to groom Hillary’s legs while Hillary prepped for an interview. In the moment, Hillary reflects: “My life had changed overnight, and this was who I had become — a person whose legs were shaved by someone else, in a taxi.” When the former deputy offers this memory to the public, the resulting media frenzy is equal to what followed Trump’s Access Hollywood tape. Unlike Trump, Hillary is held accountable, and forgiven only after denying harassment claims while admitting wrongdoing, explaining the intimate chaos of a campaign while expressing regrets, and assuring the public that she makes mistakes, but rarely! She is flawed, but only to the precise extent that you believe yourself to be flawed.

Drafting Rodham, Curtis Sittenfeld would have known that Hillary Clinton did not win the 2016 election. Her task was to show how Hillary might have altered her fate by making different decisions. The decision Sittenfeld identifies as the pivot point is a personal one: Hillary remains Hillary Rodham, no one’s wife and no one’s mother. What the author could not have foreseen was that her novel would be published during a pandemic, a catastrophe that could have been mitigated by a more competent administration. Reading the book in the spring of 2020 reminds us that Hillary Clinton not only deserved to win the election four years ago, but also that we needed her to win. As it turns out, our lives may have depended on it.

Even if Sittenfeld could have predicted our country’s current crisis, she would not have offered us a savior. The shining strength of Rodham, and of Sittenfeld’s work in general, lies in the vividly imagined details, the emotional specificity and grubby minutiae that no politician would dare include in a ghostwritten autobiography. These are the details we erase from the stories we tell about our own lives. Sittenfeld fans will recall the clogged toilet in American Wife, the orange juice pork chops in Sisterland. In Rodham, we are privy to Hillary’s inability to cook anything more complicated than peanut butter toast; the group chat in which she and her brothers root for the Cubs; and Hillary, in her late 60s, wondering if she has “kissed a man on the lips for the last time”: “How could I have, but how could I not have?”

Insofar as Hillary, on the cusp of becoming the first female POTUS, appears contrived, rehearsed, exhausted, Machiavellian, flat — well, is this not painfully realistic? Authors of celebrity profiles love to note what their subjects eat, as if Jennifer Aniston’s poached salmon might be a window into her soul. Curtis Sittenfeld goes so far as to imagine that Hillary Rodham does not have the luxury of choosing what to eat, speculating that Hillary’s meals are chosen by her staff so as to seem neither elitist (sushi) nor blue collar (cheeseburger). What Hillary eats is determined by polling data. Even when she is full, she is empty.

Sittenfeld’s exploration of Hillary’s private life is so thorough — so unsparing yet empathetic — that the book itself is an exercise in democratic citizenship and accountability. In a country where power is held by an elite few in a faraway place called Washington, do we not have a right to know who these people really are? To see them, in other words, in their underwear? Sittenfeld lays bare her protagonist’s humanity, both to prove that Hillary was the superior option in 2016, and to ask whether Americans do not ultimately deserve a better leader than her.

When I reached Rodham’s final pages, Sittenfeld’s version of events felt realer to me than real life. It was a moment of reprieve: in Rodham, Sittenfeld gives us what we need, while driving home the point that our elections do not. And it’s a little bit excruciating, watching how Sittenfeld makes her narrative so easy, so sweet, to believe. Her novel is more balanced, more resonant, more meticulously depicted than any journalistic account could be. Sittenfeld’s Rodham shows us why we read novels in the first place: because fiction reveals truths that we cannot extricate from the limited narratives of our own lives and times. While they are in progress, the stories we tell about ourselves and our society are too often incomplete and self-serving, obscured by our single-minded focus on the present and our inability to see ourselves without embellishment, without shame.

Sittenfeld’s America, and the people who rule it, will linger in the minds of her readers. Eventually, as Bill and Hillary Clinton recede from public life, the boundary between fiction and history may blur. You won’t remember which details Sittenfeld invented and which were reported in The New York Times. (Did Bill Clinton participate in Silicon Valley orgies, prompting an actress to tweet that she was cuddle puddle curious — or did Curtis make that up?) What you will remember is the pleasure of an alternate history unfolding over some 400 pages, one in which Hillary is not defeated by the man who challenged her or the man who married her. In which the job goes to the most qualified candidate. In which we see the president naked.

That the 2016 election gave us the opposite of what we needed, and that the consequences of Hillary Clinton’s loss are increasingly grave, is a hard reality to stomach. Fortunately, fiction on the level of Rodham offers some temporary relief. Who needs reality when Curtis Sittenfeld has invited us into the wilds of her imagination?

¤

LARB Contributor

Emily Adrian is the author of Seduction Theory, forthcoming from Little, Brown, as well as several other novels. She lives in New Haven, Connecticut.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Thinking About Hillary, at This Late Hour

Lorrie Moore looks back on Hillary Clinton and her complicated legacy.

In Hillary We Distrust?

Jennifer L. Pozner talks to contributors to the book "Love Her, Love Her Not: The Hillary Paradox" about why Hillary lost.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!