Scientific Rebirth

“Genesis 2.0” is a panoramic master class in the strange unmodernity of modern science.

A SCENE OF extraordinary scientific melodrama in Christian Frei’s 2018 documentary Genesis 2.0 (co-directed by Maxim Abugaev) features a squad of Siberian tusk hunters discovering a gargantuan specimen of mammoth remains in the ice of the New Siberian Islands, Russia. When the hunters hack and jackhammer the ice to free the remains, something dark oozes from the transfixed relic. Like a miraculously weeping statue, after lying entombed for thousands of years, the cadaverous mammoth bleeds. Its blood is a liquid hieroglyphic: Russian scientists on a pilgrimage from the Mammoth Museum in Yakutsk, Russia, have come to collect a sample, aiming to decode living DNA tissue and to create new mammoths today. But this moment of collection, where the scientists’ visions of regeneration collide with the scavengers’ brute excavations, proves fumbling. The travelers hold a test tube to the ice, but squander most of the bloody treasure, scooping up just a few drops of “juice.” Will they contain the living tissue they seek?

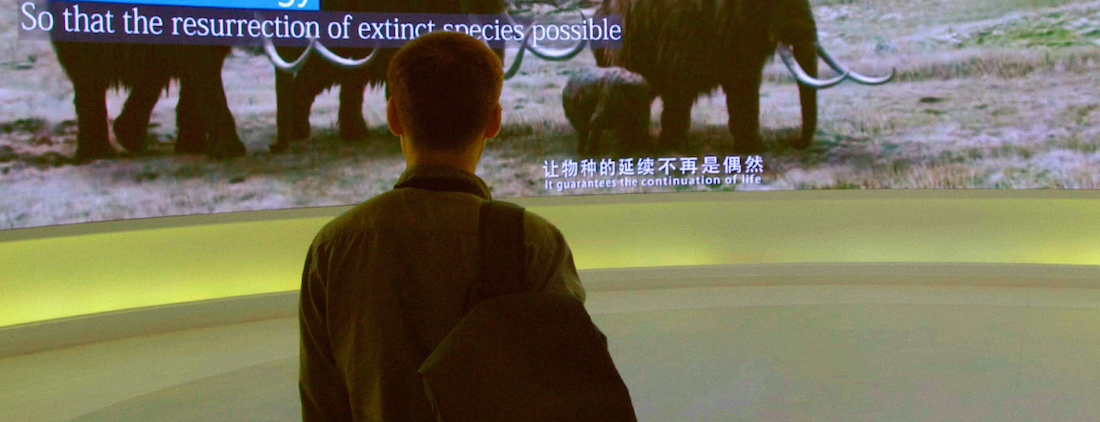

To the sound of mystical mumblings, portentous chants, and urgent techno symphonics — a score suggesting the superstitious pasts and onrushing futures that hedge this perilous quest — Genesis 2.0 follows the tusk hunters’ travails and the scientists’ travels to find the answer. The Siberian bounty hunters aren’t really going anywhere. Impoverished seasonal workers engaged in inhospitable digging, they pound the melting Arctic marsh sometimes to distraction; one named Spira appears to descend into madness before our very eyes. Meanwhile, the bloody mammoth specimen travels the world. Semyon Grigoriev, the Mammoth Museum director, couriers it to Seoul, South Korea, to consult with Woo Suk Hwang, the disgraced yet indomitable Korean cloning pioneer. But the star of the film is the Oz-like impresario of the secretive Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI), now based in Shenzhen, China: Yang Huanming. When the circumspect Grigoriev arrives at BGI with his mammoth, Yang overwhelms him with beaming ambition and terrifying enthusiasm. “God’s word is still imperfect,” Yang insists, playing with impeccable quotability to the camera, “but if we work together we can make God perfect.”

Frei concludes his documentary with rhapsodic visions of BGI as the most powerful scientific dream factory on earth, whose hundreds of sequencers Yang hopes will collect genetic information on all terrestrial organisms (the Earth BioGenome Project) and reanimate ancient life forms like the mammoth. “Life becomes big data,” Frei cautions the viewer as his camera drinks in BGI’s Promethean operation, while endlessly cutting back to the tusk hunters, who get maybe $100 each for the many kilos of tusks they sell at season’s end — perhaps enough to buy a new fridge. The gleaming genomic dream of regeneration depends on their muddy drudgery nonetheless. As Yang observes with wily understatement, “Without samples, how do we get the genome sequences?”

Frei’s odyssey dramatizes the paradox that as we push toward the future, we fall back into the past. His film is a panoramic master class in the strange unmodernity of modern science. Cutting-edge science not only needs its proles, it keeps them poor, almost like slaves. They shave using rigged car batteries and spice their food with socks. The Arctic ice they hack is melting due to warming climates, so more and more tusks are rising to the surface; the mammoths are already returning. Indeed, some urge that to survive our ecological future, we must now plunge back into prehistory. The Russian project called “Pleistocene Park” envisions mammoth regeneration as part of a larger effort to create sustainable new (or old) climates.

Frei pans over antique maps when monsters roamed the cartographic imagination; and as we travel into the Arctic, we journey into the fears of their shamanistic hunters, who offer glass beads to propitiate the spirits of animals whose slumbering remains they fatefully disturb. Talk of sin and damnation obliges even the scientist Grigoriev (whose brother Peter features as one of the hunters) to reassure himself that his mission is motivated by science, not greed. Undaunted, geneticists such as the Rasputin-like Harvard geneticist George Church dream of creating new monsters like zorses (hybrids of horses and zebras) and reviving the mammoth. Grigoriev’s specimen retains its demonic aura even as it moves through the most clinical new laboratories. His wife Lena is unnerved by its stench, and when he takes a bite from its flesh out of curiosity, she recoils as though at some unholy intercourse with an irredeemably alien presence.

The documentary’s journey ends with the insatiable Yang, a compelling figure not just because of his magnetically inscrutable charisma, but because he embodies China’s current scientific ambitions at a pivotal moment in world history and the geopolitics of science and technology. At one level, Yang represents the latest incarnation of the universal collector — an accumulative magician who sits at the end of a vast network, giddily envisioning programs of knowledge and power via collection and documentation. Such an audacious dalliance with omniscience conjures up visions of Noah’s Ark, Carl Linnaeus cataloging the plants and animals like a new Adam, or a collector like Hans Sloane dreaming of gathering the world into a single Enlightened museum. These figures imply a “Western” genealogy for Yang. But Yang and BGI are very much heir to China’s own formidable collecting traditions, for example under the Qing dynasty, whose information state engaged in a comprehensive mapping of its expanding empire and the ethnographic documentation of its subject peoples beginning in the 17th century.

Yang and BGI represent one striking manifestation of the dramatic return to prominence of Chinese science and technology that now dominates the news cycle. Nature reported that Chinese scientific publications outnumbered American publications for the first time in 2016; BGI is the largest sequencing facility in the world; the FAST radio telescope in China’s Guizhou province is the largest telescope ever built; the Chinese recently became the first to land on the far side of the moon; and the biophysical entrepreneur He Jiankui has reportedly “edited” the genes of two Chinese infants to prevent them from becoming HIV positive. These developments represent a stunning reversal of Chinese cultural fortunes after the disastrous Opium Wars and domestic rebellions of the 19th century, and the debacles of Japanese militarism and mass poverty and starvation under Maoism in the 20th. As Europe and the United States became wealthy industrial societies, producing much of the world’s most potent science, medicine, and technology, 20th-century scholars like British sinologist Joseph Needham asked questions about why China languished and had failed to invent modern science. In our own century, by contrast, scientific progress now looks like an “Eastern” story rather than a “Western” one. FAST’s architects openly declare their pursuit of “pure science” as a sign of cultural prestige — an aspiration Needham thought the Chinese lacked. Juxtapose this with the perception that science itself — “the vital sign of modernity,” as historian Gyan Prakash has memorably described it — is now under siege in the United States.

Genesis 2.0’s international story reflects the shifting geographies of the long arc of history. Grigoriev brings his mammoth sample not to the United States or Europe, but to Seoul and Shenzhen, where Yang urges them to “work together,” echoing the rhetoric of harmonious cooperation in President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative, through which China is investing, building, and leveraging relationships on an extraordinary worldwide scale through technology and infrastructure projects. Americans like George Church figure, by contrast, as illustrious if peripheral consultants. The sense of scientific progress shifting “eastward” is captured subtly but indelibly on a tour of BGI where a potted history of genetics relegates pioneers like Francis Crick, James Watson, and Craig Venter to being a mere prelude to what China will now accomplish by virtue of its economic might and political centralization. As world historians such as Peter Frankopan suggest, the implications are potentially momentous, involving nothing less than a reversion to the primacy of Asia that existed before the Industrial Revolution, and where questions about what went wrong? — including Needham’s on Chinese science — may now be turned back on the United States and Europe with potentially volatile political consequences.

Frei’s film is a melodramatic delight, but its seductive vision calls for caution. He’s not really interested, for example, in revealing that no living tissue was ultimately extracted from Grigoriev’s mammoth. He doesn’t contextualize figures like Church or Yang, inviting viewers instead to react to these brilliantly dynamic, if vaguely lunatic, scientific confidence men and their projections of godlike power. And you’d never guess that BGI has been critically in debt for most of its existence from the air of mysterious impregnability with which Frei imbues it. There is more than a whiff of ethical warning when a Swedish-American geneticist named Olson voices concerns about the mass sequencing of Chinese citizens’ DNA, which fall on utterly deaf ears at BGI. What are the dangers of collecting so many people’s genetic information, and who will use it and how? Recent reports on China’s surveillance of its minority Muslim Uighur population suggest one dark answer.

It is, however, crucial to remember that Cisco Systems and Google assisted the Chinese government in restricting internet access, that He Jiankui’s gene “editing” was performed using the American-made CRISPR technology, that Facebook shares data with electronics firms who work closely with Beijing, that the Massachusetts-based company Thermo Fisher Scientific sold China equipment used to monitor its citizens (they have now ceased doing so), and that an extremely large number of Sino-American scientific collaborations are ongoing. Nationalist rhetoric notwithstanding, we continue to live in a world of global entanglement where ethical criticism of countries like China demands frank scrutiny of envious Westerners’ own pursuit of profit and influence as latter-day Jesuits returning to court fabled Asian wealth.

While Frei theatrically reaches for mythical themes on the nature and future of “life” itself, the political questions raised by the return of Chinese science seem just as immediate. Is the long-cherished historical narrative of science and modernity as an essentially “Western” and liberal story based on free inquiry and driving social-democratic progress now in eclipse — and what will take its place?

¤

LARB Contributor

James Delbourgo is professor of history at Rutgers University, where he teaches the history of science, collecting and museums, and the history of the Atlantic World. His most recent book is Collecting the World: Hans Sloane and the Origins of the British Museum (Harvard University Press, 2017; published by Penguin Books in the United Kingdom as Collecting the World: The Life and Curiosity of Hans Sloane), which won the American Historical Association’s Leo Gershoy Award and the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies’ Louis Gottschalk and Annibel Jenkins prizes. His current research projects include a history of science in global perspective, entitled “The Knowing World,” and a history of the figure of the collector, entitled “Who is the Collector?”

LARB Staff Recommendations

Acquisition and Empire: On James Delbourgo’s “Collecting the World”

On the origins of the British Museum.

Biopower in the Era of Biotech

"Scientists are increasingly testing public trust." Jim Kozubek on the hazards of new biotechnologies.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!