Revising the First Draft of the World: On Sheila Heti’s “Pure Colour”

Sheila Heti’s new novel is a tale about grieving during the Anthropocene.

By Esmé HogeveenMarch 23, 2022

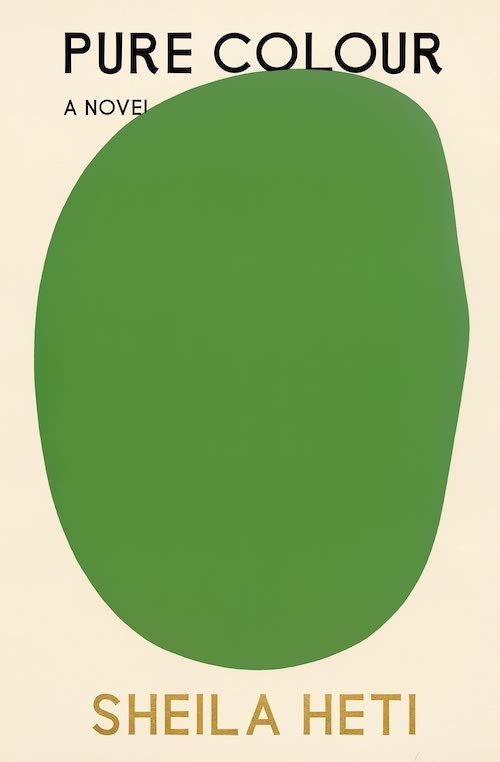

Pure Colour by Sheila Heti. 224 pages.

“AFTER GOD CREATED the heavens and the earth, he stood back to contemplate creation, like a painter standing back from the canvas. This is the moment we are living in — the moment of God standing back. Who knows how long it has been going on for?” So begins Sheila Heti’s new novel, Pure Colour. Heti has made a habit of starting books with grand, philosophical questions. Her critically acclaimed 2012 novel, How Should a Person Be?, begins by asking the titular question. The Chairs Are Where the People Go (2011), co-written with Misha Glouberman, bears the subtitle “How to Live, Work, and Play in the City” and features chapters that explore existential questions underpinning daily life. Heti’s recent “semi-autobiographical” novel Motherhood (2018) opens with a description of the I Ching, a method of flipping coins to divine answers — a technique she uses to query her creative purpose. That Heti invokes the Book of Genesis on the first page of Pure Colour, then, feels fitting, if ambitious. With each book, her scope seems to widen, and Pure Colour ushers the reader further from roman à clef or autobiography and closer to a kind of speculative philosophy or myth.

In narrative terms, Pure Colour tracks the emotional and psychic life of a protagonist named Mira. When the novel opens, Mira is young woman living in Toronto — or, rather, familiar street names lead me to assume the story is set in Heti’s own hometown. “Mira left home,” Heti writes in an early passage. “Then she got a job at a lamp store. The lamp store sold Tiffany lamps, and other lamps made of coloured glass. Each lamp was extremely expensive.” Mira’s tedious work seems simultaneously to dull and heighten her senses, an aesthetic perspective that is later honed when she is “accepted into the American Academy of American Critics.” Over the course of the novel, Mira also falls in love with a mysterious woman named Annie and mourns the death of a beloved father. Though her feelings toward Annie and her father form the story’s emotional core, Mira’s focus oscillates between considering the details of her own life and broader questions about art and existence, giving the book a meditative and at times almost spiritual quality.

In many respects, summarizing Pure Colour by describing its plot, which is quite scant in conventional terms, misses the point. The narration shifts between describing Mira’s experiences and postulating more broadly about God’s intentions in creating the “first draft” of the world. In the opening pages, readers learn that there are three types of people: birds, fish, and bears. “People born from these three different eggs will never completely understand each other,” the narrator explains, subsequently confirming that Mira is a bird, Annie a fish, and Mira’s father “a warm bear.” Within this tri-species taxonomy, directional perspective correlates strongly to how individuals literally and figuratively regard the world. Birds observe from a distance and “are interested in beauty, order, harmony and meaning”; fish are bound in a collective and “concerned with fairness and justice here on earth”; and bears care most about their immediate surroundings and “are turned towards those they can smell and touch.” The tensions between these different worldviews are central to the story and Pure Colour’s meta-subject is how different relationships to art and criticism allow humans to interpret, cope, exalt, and otherwise find meaning in life.

Pure Colour’s two sections — the account of Mira’s life and the passages considering divine or universal purpose — are voiced by similar, if not identical, omniscient narrators. In effect, there is a fable-like quality to the storytelling. Surreal events, such as when Mira’s spirit enters a leaf with her father after his death, are relayed matter-of-factly. This measured tone is also reflected in the syntax: Heti uses a mixture of short phrases and long sentences broken into multiple clauses to organize stream-of-consciousness ideas into causal observations, as in: “The day after her father died, Mira saw that she could abandon her whole life, walk away from it, and it wouldn’t matter.” The direct prose, as well as the narrator’s tendency to circle back and reconsider ideas, evokes the process of mulling things over during a long walk or an extended period alone — the parallels with isolated thinking during the pandemic are not lost on the reader.

Whether pondering metaphysical or minor topics, Mira often observes patterns and gaps in her own thought processes. In some ways, Mira’s gestures toward self-reflexivity and self-critique make it easy to read her as a product of the mindfulness era. She’s by no means perfectly self-aware or prophetic; rather, Mira comes across as genuinely curious. At times, drawing connections between seemingly abstract or historical topics and her present-day emotions or realities causes her to become overwhelmed. For instance, reflecting upon the Bronze Age as part of a stream-of-consciousness thought spiral, the narrator suddenly thinks: “Because you know what, if we suddenly went back two thousand years, there’d be nothing we could do to speed things along. I don’t know how to make a steam engine.” This rare first-person invocation, and the abrupt introduction of a new subject (on the previous page, Mira was describing her father, not historical progression or steam power), reveals a mind racing to find coherence in the wake of personal disaster. What’s unique about Mira’s self-reflexivity, at least within Heti’s oeuvre, is that she searches for answers without a desire for action. Perhaps typical for a bird person, Heti’s narrator seeks understanding, or at least interpretation, for its own sake.

Heti is known for experimenting with form as a means of representing self-awareness. How Should a Person Be?, her breakthrough novel, depicts intimate scenes from Heti’s own life and incorporates transcripts from conversations with her friend and collaborator, the painter Margaux Williamson. Similarly based on events from Heti’s life, Motherhood chronicles the author’s conflicting desire and disinclination toward parenting and employs the I Ching to answer questions like: “Will reading help my soul?”; “Is art at home in the world?”; and “[C]an a woman who makes books be let off the hook by the universe for not making the living thing we call babies?” How Should a Person Be? and Motherhood are both voiced in the first person and feature narrators who learn about themselves through interacting with, and judging, others. It’s notable, then, that Heti shifts to using a close third person for most of Pure Colour and that the characterization of the critic Mira’s voice feels less developed than those of the writer protagonists in Heti’s earlier works. In an apt review in 4Columns, Jennifer Kabat observes that “the writing is warm, deft, and strange, but the characters are thin and the plot is too.” I’m inclined to agree and initially struggled to articulate my response to the book. With time, though, I’ve found a growing appreciation for Mira’s resistance to what a recent New Yorker article called “main character energy” and for Heti’s own anti-novelist stance.

The more the story — if we can even call it that — develops, the more Pure Colour becomes a tale about grieving during the Anthropocene. The writing’s alternately rough and delicate slowness reads like a modern benediction. “Now the earth is heating up in advance of its destruction by God, who has decided that the first draft of existence contained too many flaws,” Heti writes. We learn that God, “[r]eady to go at creation a second time, hoping to get it more right this time, […] appears, splits, and manifests as three art critics in the sky: a large bird who critiques from above, a large fish who critiques from the middle, and a large bear who critiques while cradling creation in its arms.” For bird-descendent Mira, criticism is a means of apprehending not only culture but also human beings. Looking closely, however, risks opening the door to both beauty and despair. The narrator explains: “It’s true that the world was failing at its one task — of remaining a world. Pieces were breaking off. Seasons were becoming postmodern.” In this world, “[t]he ice cubes were melting. The species were dying.” Though Mira may have drawn on the rhetoric of art criticism to fathom abstract, global loss, her father’s death upsets her very sense of self and renders her unmoored, a bird flying through a storm.

By Heti’s own explanation, she didn’t set out to write about grief, but her father’s death in 2018 influenced the course of Pure Colour. In 2020, Heti published an essay in The Yale Review titled “A Common Seagull: On Making Art and Mourning” in which she shares a memory that may well have inspired Mira going into the leaf. “Walking in the forest with my dog a few weeks after my father died, I noticed the green of the fir trees; the colors were so muted and beautiful,” Heti recalls, continuing:

I felt in that moment as if I had never really looked at colors before, I stood wondering beneath the shadowless sky whether, when my father died, the spirit that had enlivened him passed into me, for I had held him as he died; as perhaps when his father, a painter, died, his spirit went into my father, so that now I had the spirit of my father and the spirit of my grandfather both inside me. And I wondered whether this influence — the spirit of my painter grandfather inside me — was why I was suddenly noticing colors.

This quotation reads like a map for Pure Colour, in which the father promises the child Mira that one day he will buy her “pure colour — not something that was coloured, but colour itself!” Bird Mira’s childhood belief in her father, a bear who desires closeness and proximity, eventually gives way to a sense of guilt. “As Mira got older, it became harder to love [her father] in the proper dimensions, or even to know what those were,” the narrator explains, as “any interest she developed in another person felt like it was taking something from him, since he had no one to love but Mira.” Nevertheless, when her father dies, it is Mira who wishes to follow and “[draw] him halfway back.”

Heti’s writing is sometimes described as “strange,” a description most often invoked in the context of praise. Pure Colour extends this fundamental strangeness in new directions, with varied results. At times, the tapestries Heti weaves to relay hyper-imaginative conceits feel overstretched: while reading, I kept picturing a loose mohair knit — the kind of delicate, expensive garment often advertised to me on Instagram. The book’s metaphorical threads are glimmering and attractive, but the wide spaces left between some of its ideas create opportunities for snags. For example, the notion of a second draft of the world, and of God as a critic examining defects in the first draft (the world that Pure Colour’s characters and readers occupy), is exciting. The notion that art’s vitality may no longer be appropriately measured by means of its endurance in this fast-dying world is also poignant. Some of the nuances of Heti’s ideas, however, are lost or diminished due to a hazy internal structure. Is God a critic? Are all human beings? Is Annie, the orphan whom Mira claims to adore yet knows so little about, vaguely sketched because of the limits of Mira’s perspective or because character building is unimportant in Heti’s novel-cum-mythology? Because Pure Colour is light on plot, losing the proverbial thread doesn’t so much threaten our understanding of the text as our very engagement with it.

Heti is a question asker, and Pure Colour is rich in queries that link the personal with the universal. In the past, the conceptual richness of Heti’s questions led critics to speculate about the influence of Judaic mysticism or forms of aesthetic philosophy on her writing. In a 2019 interview in Guernica, the author remarked: “I don’t think my characters actually make decisions based on what they get from mystical or supernatural sources; looking in that direction indicates a kind of desperation for meaning, but the final answers never come from those places.” In Pure Colour, Mira isn’t consumed with taking up or disputing specific intellectual or spiritual traditions. Instead she accepts the mutable nature of meaning and strives to hone a personal framework for interpretation. To this end, Pure Colour’s roving subject matter and looping motifs embody the surrealistic mix of clarity and discombobulation that accompany grieving. As a writer, Heti has a special talent for making the mundane feel magical — this is key to the beguiling strangeness of her texts. The most moving parts of Pure Colour arrive when Mira seeks emotional and aesthetic truths in spaces between the profound and the everyday, inviting readers — birds, fish, and bears alike — to witness the depth of the protagonist’s (and the author’s) mental perambulations.

¤

LARB Contributor

Esmé Hogeveen is a writer and editor based in Toronto. She is a staff writer at Another Gaze and a Film and ArtSeen contributor at The Brooklyn Rail. Her writing on art, film, culture, and aesthetics has appeared in Artforum, Bookforum, The Baffler, BOMB, Frieze, Hazlitt, Hyperallergic, GARAGE, Canadian Art, C Magazine, Texte zur Kunst, and cléo film journal, among other venues. She holds an MA in Critical Theory and Creative Research from the Pacific Northwest College of Art and subsequently studied at Cornell University’s School of Criticism and Theory.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Fundamentally Absurd Question: Talking with “Motherhood” Author Sheila Heti

Kate Wolf interviews “Motherhood” author Sheila Heti.

This Shirt Won’t Change Your Life: An Interview with Sheila Heti

Women in Clothes: Women talking to women about women’s relations to women’s clothing.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!