Resuscitating the Psychedelic Sensibility

Jon Savage’s "1966" looks at a pivotal year in history via its music.

By James PennerJuly 27, 2016

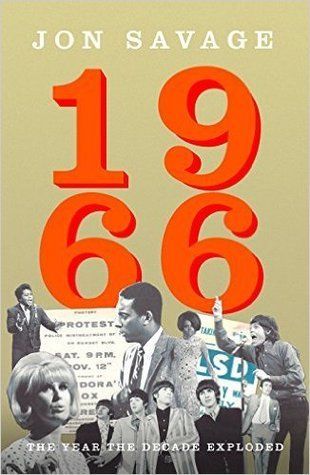

1966: The Year the Decade Exploded by Jon Savage. Faber & Faber. 620 pages.

IN THE LAST DECADE, there have been a host of books that focus on the historical significance of one particular year. Christian Caryl’s Strange Rebels: 1979 and the Birth of the 21st Century (2014), Ian Buruma’s Year Zero: A History of 1945 (2013), and Andreas Killen’s 1973 Nervous Breakdown: Watergate, Warhol, and the Birth of Post-Sixties America (2006). Jon Savage’s 1966: The Year the Decade Exploded makes a contribution to this emerging genre by boldly proclaiming that 1966 was a vibrant cultural moment that merits our attention some 50 years later.

Unlike Buruma and Caryl’s studies, Savage, a London-based music journalist and cultural historian, is not necessarily interested in political upheavals that cause seismic shifts in the geopolitical order. Instead, Savage is fascinated with pop music and the micro-events that cultural historians typically overlook. For Savage, the 45-rpm single is the ideal micro-event because it encapsulates how people were feeling and thinking at a particular moment. For the author, 1966 is crucial because it was the last year the 45 outsells the LP. Thus, 45s become Savage’s central primary sources in his cultural history:

I was attracted to 1966 because of the music and what I hear in it: ambition, acceleration, and compression. So much is packed into the 45s from this period: ideas, attitudes, lyrics, and musical experimentation that in the more indulgent years to come would be stretched out in thirty-five minute to forty minute albums. Condensed within the two-to three-minute format, the possibilities of 1966 are expressed with extraordinary electricity and intensity.

To fully appreciate Savage’s contention that 1966 represents a peak moment in the evolution of pop music, we need to understand that the genre of pop music was frequently derided in the 1950s and early 1960s. For many sober-minded adults who had lived through World War II, pop was mindless escapism for children and teenagers; its importance was debated, and in some cases, was regarded as only slightly more important than the hula-hoop and the yo-yo. (The best example of this is Dwight MacDonald’s “Masscult and Midcult” (1960); MacDonald dismisses action painters, Beat poets, and the entire genre of rock ’n’ roll.) Within this context, Savage argues that pop music — as an aesthetic form — achieved maturity and cultural importance in 1966, the progression seen in The Beatles, who advance from earlier innocent pop songs about love and courtship (“I Want to Hold Your Hand”) to songs about existential alienation (“Eleanor Rigby”) and the experience of LSD (“Tomorrow Never Knows”).

Savage’s pointed focus on pop music appeals to me because I have always been fascinated with pop music from the 1960s. As a lapsed mod with psychedelic leanings, I have always had a reverence for 1966, the year when the sharp dressing mods started to grow their hair longer and wear colorful paisley shirts. Not simply a sartorial statement, it also reflected an inward turn — the moment when pop musicians began to experiment with consciousness-expanding drugs. 1966 is unique in the sense that it represents a utopian moment of transformation and rebirth. It’s the cultural moment of the proto-hippie and an embryonic moment for the formation of the counterculture.

John Lennon dons a paisley print shirt during the photo shoot for Revolver in 1966. The clothes were bought at the legendary Granny Takes a Trip boutique on Kings Road in London.

Savage attempts to move away from the historical clichés (“Swinging London” and “Cool Britannia”) that are often invoked when the era is discussed. He does not attempt to reproduce “Swinging London,” as it was, nor does he attempt to revisit the glorious year that England won the World Cup. Instead, the author combs the British and American music charts for songs that stand out from the schlock of the era. The singles that he selects become a template for discussing issues and social movements (the Women’s Movement and Homophile movement) that are beginning to surface in the culture at large. Since pop music is everywhere in 1966, his historical project is not limited to one specific geographical location. While London occupies a central role in Savage’s study, the author also frequently migrates to the other important pop meccas of the mid-1960s: The Sunset Strip in Los Angeles, Warhol’s Factory in Manhattan, and the San Francisco scene.

Throughout 1966, music is given an elevated status because it can function as both a cultural and aesthetic trigger. Music is the sui generis art form, because it constitutes a buried form of consciousness that can be resurrected when received with attentive ears. In Savage’s first chapter, Simon & Garfunkel’s “The Sound of Silence” (which reached number one in January 1966) is thematically linked to Peter Watkins’s hybrid documentary film, The War Game. The climax of Watkins’s film is the cinematic experience of nuclear annihilation: “the screen fills with white, and then the image turns negative; all you hear is the scuffling of limbs and the whimpering of humans in distress. The silence is the sound of life being sucked out of the world.” For Savage, silence becomes a metaphor for not only alienation, but also the shadow of nuclear annihilation that hangs over the postwar generation. During the early 1960s, it was noted that World War I ended in 1918 and that World War II started in 1939. The interim period between the World Wars was a mere 21 years. If history repeats itself, the next war would arrive in 1966. As such, the younger generation of the early 1960s often adopted an existential attitude toward life. 1966 also traces how an oppositional culture emerges in the shadow of the imagined nuclear holocaust. Peter Jenner, the manager of Pink Floyd, describes the utopian yearnings of the ’60s as a “New Jerusalem”:

I think we were the last generation, in a way, still hoping to build the new world. Our world was free love and drugs and rock ’n’ roll, and alternative societies, being ourselves. It wasn’t Marx, particularly, it certainly wasn’t the Cold War. The nuclear paranoia was huge. The implicit thing was that we had to build a new world before we get blown up.

Fundamental to the nascent counterculture was the concept of deconditioning: the younger generation’s futuristic desire to reject its repressive cultural inheritance.

In 1966, Savage’s goal is to identify the emerging counterculture by describing all of its parts. He devotes chapters to the emergence of the antiwar movement (March), the ubiquity of LSD (April), the first stirrings of the Women’s Movement (May), the Civil Rights movement and Black Power (July), and the Homophile and underground Gay Rights movement (August). There are certainly many high points in Savage’s historical account of 1966. However, for me, the most compelling chapter is April 1966; it documents the remarkable convergence of psychedelic drugs and pop music at the time LSD was still legal.

For many pop musicians who are coming of age in the mid-1960s, psychedelic drugs function as a rite of passage. The experience of altered consciousness becomes a literal expression of the oppositional culture that young people aspire to create and embody. 1966 documents the cultural reach of LSD: how it permeates youth culture and how it changes the way people experience music. LSD’s most immediate contribution is the creation of a new genre of music: psychedelic pop.

A key micro-event of 1966 was John Lennon’s composition of “Tomorrow Never Knows.” In March 1966, Lennon visited Barry Miles’s Indica Bookshop looking for some Nietzsche, yet he ended up buying a copy of Timothy Leary/Richard Alpert/Ralph Metzner’s The Psychedelic Experience. When Lennon returned home from the bookshop, he took LSD and became fascinated with a line from the introduction: “Whenever in doubt, turn off your mind, relax, float downstream.” Lennon’s epic LSD trip eventually became a song about the experience of ego death (“Lay down all thoughts, surrender to the void”). Savage recreates the micro-event when he describes the song’s visceral effect on the listener: “Tomorrow Never Knows” was acid. Swerving and swooping through the sound mix, the overdubs captured the ebbs and flows, zaps and zings of LSD’s perceptual overload, while the overall drone — established on the final version by the opening tambour — harmonized with the synesthetic lyrics: “listen to the color of your dreams.” This was the drug as interpreted by Leary and Aldous Huxley: “Love is all and love is everyone.” In its final version, “the song sounded like the jet stream, marking a change in the weather.”

The last four chapters of Savage’s 1966 are labeled “Explosion.” These chapters contain various singles that signify a sea change in pop music. November belongs to the Beach Boys, “Good Vibrations” representing the locus classicus in psychedelic pop music primarily because it mirrors the sensorial explosion that is LSD:

“Good Vibrations” is saturated in heightened perception, whether the switchback in mood and texture created by all the edits, or the extremely precise and vivid detail of texture, color, and smell contained in words like “blossom” and “perfume” and phrases like “the way the sunlight plays upon her hair.” Just as the experience of LSD prompted users to begin examining the potential of the brain, so the deeper meaning of the song is actually concerned with the non-verbal communication: subtle feelings, even telepathy, and ESP.

Savage also covers the Beatles’s final American tour and the burning of Beatles records and memorabilia in various Southern cities. Fundamentalist Christians were furious with John Lennon’s suggestion that the Beatles were “more popular than Jesus.” Although Lennon’s comments had been taken out of context, the image of Southern whites burning Beatles records in nocturnal settings invited comparisons to the notorious Nazi book burnings of the 1930s.

When Brian Epstein was told of the Beatles bonfires in Birmingham, he remarked: “Do you think it is becoming of anyone in Birmingham to criticize the Beatles? Because Birmingham is known all over Europe as the place where the negro is treated so badly.” The Beatles bonfires of August 1966 did not succeed in the sense that they failed to halt the Beatles’s widespread popularity in the United States. On the contrary, the Beatles bonfires seemed to draw attention to pop music’s tremendous cultural influence. Pop music could no longer be dismissed as “faddish” and “disposable”; its cultural influence and hold on youth culture were undeniable.

1966 is also the year of cultural backlash. It was the year when cultural authorities, for the first time, began banning and censoring pop songs that contained drug references. The year’s first casualty in the censorship war was The Byrds’s “Eight Miles High.” The Gavin Report, an influential publication in the radio industry, declared that it had dropped “Eight Miles High” from its recommended playlist: “In our opinion these records imply encouragement and/or approval of the use of marijuana or LSD. We cannot conscientiously recommend such records for airplay, despite their acknowledged sales.” There was also fallout in the UK when a Birmingham city councilor asked Home Secretary Roy Jenkins to have the BBC ban “Eight Miles High” and Bob Dylan’s “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35.” The latter attempts at censorship were the first skirmishes in the cultural and legal war against psychedelic drugs. Anti-drug hysteria reached its apex when LSD was declared illegal in the United States in October 1966.

Savage’s 1966: The Year the Decade Exploded makes a vibrant and important contribution to our understanding of the 1960s. Using the prism of pop music, the author manages to recover the rich aesthetic legacy of 1966 and reminds us that pop music can be a vital and affective medium for resurrecting the buried consciousness of history. In Savage’s vision, 1966 becomes a wondrous moment of transformation and untapped potential, a moment when pop music seemed to move forward in a joyous and fearless trajectory.

¤

This piece is dedicated to Michael Quercio of the Three O’ Clock. Michael turned me on to 1966 in 1983.

¤

LARB Contributor

James Penner is the editor of Timothy Leary: The Harvard Years (2014) and the author of Pinks, Pansies, and Punks: The Rhetoric of Masculinity in American Literary Culture (2011).

LARB Staff Recommendations

David Bowie and the 1970s: Testing the Limits of the Gendered Body

David Bowie and the 1970s: Testing the Limits of the Gendered Body

Culture War: What Is It Good For?

Andrew Hartman's detailed account of the extended "shouting match" about America's identity, a.k.a. the culture wars.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!