David Bowie and the 1970s: Testing the Limits of the Gendered Body

David Bowie and the 1970s: Testing the Limits of the Gendered Body

By James PennerJanuary 2, 2016

Enchanting Bowie by Christopher Moore, Sean Redmond, and Toija Cinque. Bloomsbury Academic. 368 pages.

Future Nostalgia by Shelton Waldrep. Bloomsbury Academic. 232 pages.

AT THE AGE OF THREE, a young David Bowie discovered some makeup in the upstairs bedroom. He put lipstick, eyeliner, and face powder all over his face, and when his mother caught him in the act, she was startled by his transformation: “[F]or all the world he looked like a clown.” Although amused at first, she warned him not to play with makeup because “makeup wasn’t for little boys.”[i] A cursory glance at the rock star’s extensive career reveals that his childish fascination with the outré has never actually waned. When Bowie first discovered rock music in the 1950s, he was consciously aware of the medium’s inherent theatricality and the ways in which rock music could become a conduit for radical forms of self-transformation.

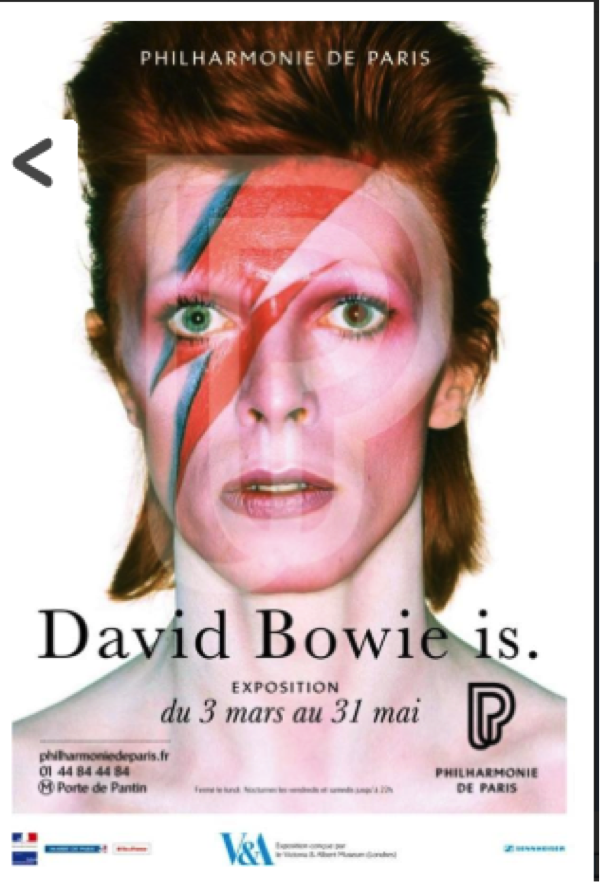

Bowie’s avid interest in aesthetic self-reinvention is certainly a familiar theme in the rising academic field of David Bowie Studies. In 2015 alone, there have been three scholarly books about David Bowie: David Bowie: Critical Perspectives (Routledge), Enchanting David Bowie: Space/Time/Body/Memory (Bloomsbury Academic), and Future Nostalgia: Performing David Bowie (also Bloomsbury Academic).[ii] These books come on the heels of the highly successful David Bowie is… exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 2013, which includes over 300 objects from David Bowie’s personal archives in Switzerland — his outlandish costumes, rare album covers, handwritten lyrics, unseen photographs, and movie posters from a career that has spanned over five decades. At present, the exhibit has toured Chicago, Toronto, São Paulo, Berlin, Paris, Melbourne, and is heading to Groninger Museum in the Netherlands.

Two of the scholarly books — Future Nostalgia: Performing David Bowie (2015) and Enchanting David Bowie: Space/Time/Body/Memory (2015) — insist that Bowie should not be viewed simply as a rock musician: Bowie’s ongoing cultural performance is an elusive and pliable text that can be read and reread from various critical vantages. But the business of unpacking the text that Bowie leaves behind is a serious interpretive challenge. Shelton Waldrep, a Victorian scholar and a leading scholar in David Bowie Studies, has been teaching a senior thesis course (“The Phenomenology of David Bowie”) for over 10 years at the University of Southern Maine. His cultural studies course, which sits alongside traditional courses on Shakespeare, Dickens, and Joyce, rigorously attempts to dissolve the existing boundaries between high culture and low culture. His book, Future Nostalgia: The Performance of David Bowie, attempts to trace every discernible cultural and aesthetic influence on Bowie’s work. From performance traditions (commedia dell’arte and Lindsay Kemp) to visual culture (German Expressionism, Duchamp, Dada) to the literary artists (the cut-ups of William S. Burroughs and the dystopian works of J. G. Ballard), Waldrep’s capacious approach to Bowie’s eclectic body of work persuasively suggests that Bowie’s oeuvre should be interpreted with a wide-angle interdisciplinary lens.

Future Nostalgia emphasizes Bowie’s fascination with theatricality and artifice. Waldrep connects Bowie to the l’art pour l’art tradition of the 19th-century; thus, Bowie’s creation of Ziggy becomes a bold example of Wildean self-fashioning for the late 20th-century: “Bowie’s art crosses boundaries of art and reality, inside and outside, subject and object. He pulls the world into his art, but his art also expands outward to aestheticize the world, a different version of the total artwork.” In 1972 and 1973, Ziggy’s aesthetic performance never really ends because Bowie performs Ziggy on and off stage and during his interviews with the music press.

In Future Nostalgia, Bowie’s dandyish celebration of the artificial stands in direct opposition to the “ideology of authenticity” that was so central to the rock zeitgeist of the 1960s (Bob Dylan being perhaps the best example of this trend).[iii] Bowie, a self-confessed poseur, was fond of shocking rock critics with his rejection of authenticity: “I feel like an actor when I am on stage, rather than a rock artist.”[iv] Bowie even remarks that “I don’t profess to have music as my big wheel and there are a number of other things as important to me apart from music. Theatre and mime, for instance.”[v]

While Future Nostalgia encompasses several decades from Bowie’s career, it highlights the importance of Bowie’s golden period: the 1970s. During the age of glitter, Bowie was astonishingly productive, releasing no less than 11 albums, an album of covers (Pin Ups), and two live albums (David Live and Stage). Waldrep provides articulate readings of Bowie’s four classic albums from the early and mid 1970s: Hunky Dory (1971), The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972), Aladdin Sane (1973), and Diamond Dogs (1974), but also has quite a lot to say about the importance of the Berlin trilogy (Low (1977), Heroes (1977), and Lodger (1979)) and the album that bookends Bowie’s remarkable output of the 1970s, Scary Monsters and Super Creeps (1980).

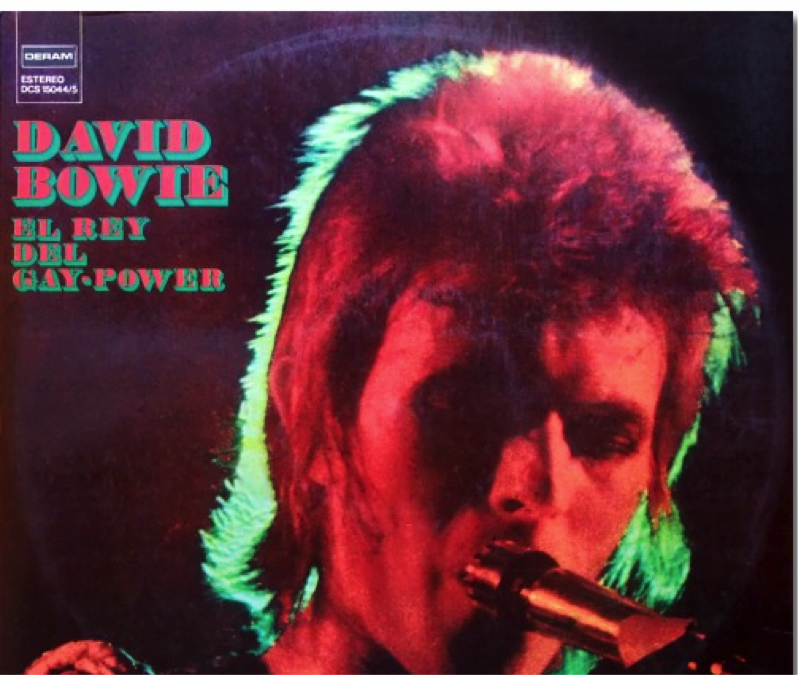

Most salient is Waldrep’s analysis of Bowie’s contribution to gender-role subversion in the early 1970s. Bowie’s creation of Ziggy Stardust, the bisexual space alien-cum-rock star and his androgynous appearance on the cover of Hunky Dory and The Man Who Sold the World generated myriad misreadings in the 1970s. For example, in Spain and Latin America in the mid-1970s, a collection of Bowie’s music was titled simply, “David Bowie: El Rey de Gay Power.”

The Spanish Collection (Deram, 1973) highlights the popular tendency to interpret Bowie’s music as a product of the Gay Liberation protest movement, and Future Nostalgia attempts to complicate this one-dimensional reading of Bowie’s music and performance, arguing that Bowie’s tacit aim was the notion of “sexual undecidability”: a performance of gender that was outside the prescribed boundaries of the heterosexual/homosexual binary. The author notes that,

[I]n the world of Ziggy this sexuality seems especially marked by Ziggy’s seductive powers, his function as locus of attraction because he is alien, futuristic, or even god-like. In that sense, he functions as the exception, the male figure who is so inspiring, that it is not transgressive for men to be attracted to him. He opens up an alternative terrain where it is possible that his followers, male and female, are both his lovers.

By destabilizing what might be termed the heterosexual imperative of rock music, Bowie, in toto, “presents an alternative mainly to the straight male sexuality—one that is not gay, but allows for the possibility of feminine self-expression or of same sex erotics.” Waldrep asserts that most of Bowie’s performances in the 1970s

[…] seem to be closer to a pastiche of gender in which Bowie places the codes of maleness and femaleness (or really masculinity and femininity) next to each other. His own body is reinscribed in such a way that both its male characteristics (strong legs, tall stature) and its female ones (narrow shoulders, large eyes) are called attention to. Not only is the result not drag but it is not androgyny either.

In musical terms, Bowie’s performance of gender role subversion is also conveyed in his lyrics. A few of his songs are coded as “gay” (“Queen Bitch” and “John I am only Dancing”) while Bowie is also quite fond of penning cock rock anthems like “Suffragette City” (“Wham Bam Thank You Mam”) and “Hang on to Yourself” (“she wants my honey not my money, she’s a funky thigh collector”). In each case, the overall effect of Bowie’s music and on-stage performance is to create a state of gender blurriness. As such, it’s not surprising that Bowie’s mythic performance of masculinity has a different effect on various sexual identities:

If gay men felt themselves reflected in Bowie[’s performance of masculinity] and straight men that they were being given permission to be something else, then for women Bowie represented, to some extent, themselves as they frequently encountered the world — as subject and object together.

Waldrep also links Bowie’s performance of Ziggy to futurity: “a future that has yet to happen, that is arguably a utopian project of the (then) present, but that also does not have an actual origin.” In interviews, Bowie describes this yearning as “a nostalgia for the future.”

Waldrep’s ability to interpret the chameleon twists in Bowie’s work is impressive. He unveils the autobiographical moments and presents a nuanced reading of his often-ambiguous lyrics. The song “Scary Monsters and Super Creeps” becomes a song about Bowie’s breakup with his first wife, Angela Bowie (“She began to wail jealousies scream / Waiting at the light know what I mean”). Although the author’s command of the material and the Bowie archive never waivers, reader fatigue does begin to take hold during chapters five (“Bowie and Orientalism”) and six (“Bowie and Disability Studies”). Waldrep’s extensive theoretical interpretation of Bowie’s body of work illustrates a lingering problem in the field of cultural studies: the desire to perform rigor can result in octopod-like works of scholarship that overreach in every conceivable theoretical direction. That said, Future Nostalgia is the best critical assessment of the Bowie oeuvre that we have; it deftly provides shape and form to an amorphous body of work that often seems to defy interpretation.[vii]

Much like Future Nostalgia, Toija Cinque, Christopher Moore, and Sean Redmond’s Enchanting Bowie: Space/Time/Body/Memory also attempts a multivalent approach to Bowie’s music and performance. A key theme in this collection is Bowie’s penchant for what might be termed “creative self-destruction”:

This process of renewal means that Bowie constantly ‘kills’ himself, an artistic suicide that allows for dramatic event moments to populate his music, and for a rebirth to emerge at the same time or shortly after he expires. Bowie has killed Major Tom, Ziggy Stardust, Halloween Jack, Aladdin Sane and The Thin White Duke to name a few of his alter-egos. In this environment of death and resurrection, Bowie becomes a heightened, exaggerated enigma, a figure who seems to be artificial or constructed and yet whose work consistently asks us to look for his real self behind the mask […]

If Bowie, ever the chameleon, is in the habit of leaving aesthetic corpses behind, the goal of Enchanting Bowie is to dissect them. The volume is organized around four thematic concepts: space, time, body, and memory. Thus, there are articles about a wide range of topics: Major Tom and space travel, Ziggy and urban alienation, Bowie as Modernist and Postmodernist, and Bowie and the mashup. As each article reinterprets the Bowie mythos, Bowie the artist and provocateur becomes pliable in the hands of each scholar, pulled and stretched in various thematic and theoretical directions. This may sound disconcerting to Bowiephiles and musicologists, but the end result is actually quite impressive. Bowie’s performance becomes a supple text that can be endlessly reinterpreted.

Bowie’s eyes in the Nicholas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

A good example of the cultural studies approach is Kevin Hunt’s “The Eyes of David Bowie.” Hunt’s analysis of Bowie’s anisocoria (the condition of having unequally sized pupils) becomes a way of reading Bowie’s artistic expression. When Bowie was a teen, he ended up in a fistfight over a girl with his close friend George Underwood who reportedly punched Bowie, damaging his eye. Hunt explains that the “punch accidentally scratched the eyeball, resulting in paralysis of the muscles that contract from the iris. From that day Bowie’s left pupil has remained in a fixed open position, sometimes creating the appearance of heterochromia (a difference in colour) of his irises.” In interviews, Bowie has remarked that the injury affected his depth perception: “[W]hen I am driving for instance, cars don’t come toward me, they just get bigger.” Hunt notes that “Bowie’s iconic imagery can be advanced by considering the punctuating effect of his anisocoria and how the uncanny qualities of his eyes opens up a connection with the animistic, providing a context through which to connect one key element of his body — the eyes — with his public persona as creative outsider.” Bowie reportedly thanked Underwood for the notorious injury because his anisocoria “has become a key feature of his unique character as a performer […] he has turned the physical defect of a paralyzed pupil into a positive marker of his highly inventive ability to see and be seen differently.”

Future Nostalgia and Enchanting Bowie exist alongside a seemingly endless stream of serious and sensationalist Bowie biographies. There are now over 20 Bowie biographies (Angela Bowie has contributed two herself and a new Bowie biography appears roughly every two years[viii]). In an interview, Bowie has referred to the unauthorized biographies as “a bloody cottage industry.” Bowie has also been equally skeptical about film projects that attempt to represent his musical legacy. In the 1990s, the Bowie estate denied director Todd Haynes’s request to use his back catalogue in Velvet Goldmine (1998) and, more recently, rejected Danny Boyle’s plans for a biopic musical.[ix] At the moment, Bowie has no plans to write an autobiography and there will probably never be an authorized Bowie biography. If the task of interpreting Bowie’s work is left to museum curators and cultural studies scholars, Future Nostalgia and Enchanting Bowie suggest that Bowie’s corpus at least is in capable hands.

¤

[i] Peggy Jones’s anecdote from Bowie’s childhood appears in Mark Spitz’s Bowie (Crown, 2009).

[ii] Sean Egan’s wonderful collection of Bowie interviews, Bowie on Bowie (Chicago Review Press) also appeared in 2015.

[iii] The “ideology of authenticity” is taken from Auslander’s excellent chapter on David Bowie in Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music (University of Michigan Press, 2006).

[iv] The quotation is cited in Timothy Ferris’s “David Bowie in America.” The Bowie Companion. Ed. Elizabeth Thomson and David Gutman. (New York: Da Capo Press, 1996).

[v] Shaar Murray, Charles. “David at the Dorchester.” Bowie on Bowie: Interviews and Encounters with David Bowie. Ed. Sean Egan. (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2015).

[vii] Waldrep’s reading of Bowie builds on material from Philip Auslander’s groundbreaking study, Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music. Auslander’s chapter on Bowie, “Who Can I Be Now? David Bowie and the Theatricalization of Rock” argues that Bowie’s performance of masculinity challenges “the ideology of authenticity.” When speaking of Bowie criticism,

Nicholas Pegg’s remarkable The Complete David Bowie (Titan Books, 2011) should also be mentioned. This 700-page encyclopedic volume provides an analysis of every single Bowie song, album, music video, interview, and film appearance. However, unlike Waldrep’s Future Nostalgia, it does not offer a theoretical interpretation of Bowie’s work.

[viii] The most recent one is Wendy Leigh’s Bowie: The Biography (2014); the latter could be also subtitled “The Sexual Life of David Bowie.”

[ix] This piece appeared in the Guardian in November of 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/nov/10/danny-boyle-grieving-after-david-bowie-says-no-to-musical

¤

LARB Contributor

James Penner is the editor of Timothy Leary: The Harvard Years (2014) and the author of Pinks, Pansies, and Punks: The Rhetoric of Masculinity in American Literary Culture (2011).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Facing the Music

Hynde and Brownstein tell us, with no other agenda than full disclosure, that they were lame — or in other words, lost and undone by their own desire.

Photographer Spotlight: Mick Rock Shoots David Bowie [VIDEO]

Mick Rock shares his favorite memories and photographs from his time as David Bowie's official photographer in the early seventies.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!