Relevés and Revolutions: On Jennifer Homans’s “Mr. B”

Martha Anne Toll reviews Jennifer Homans’s “Mr. B: George Balanchine’s 20th Century.”

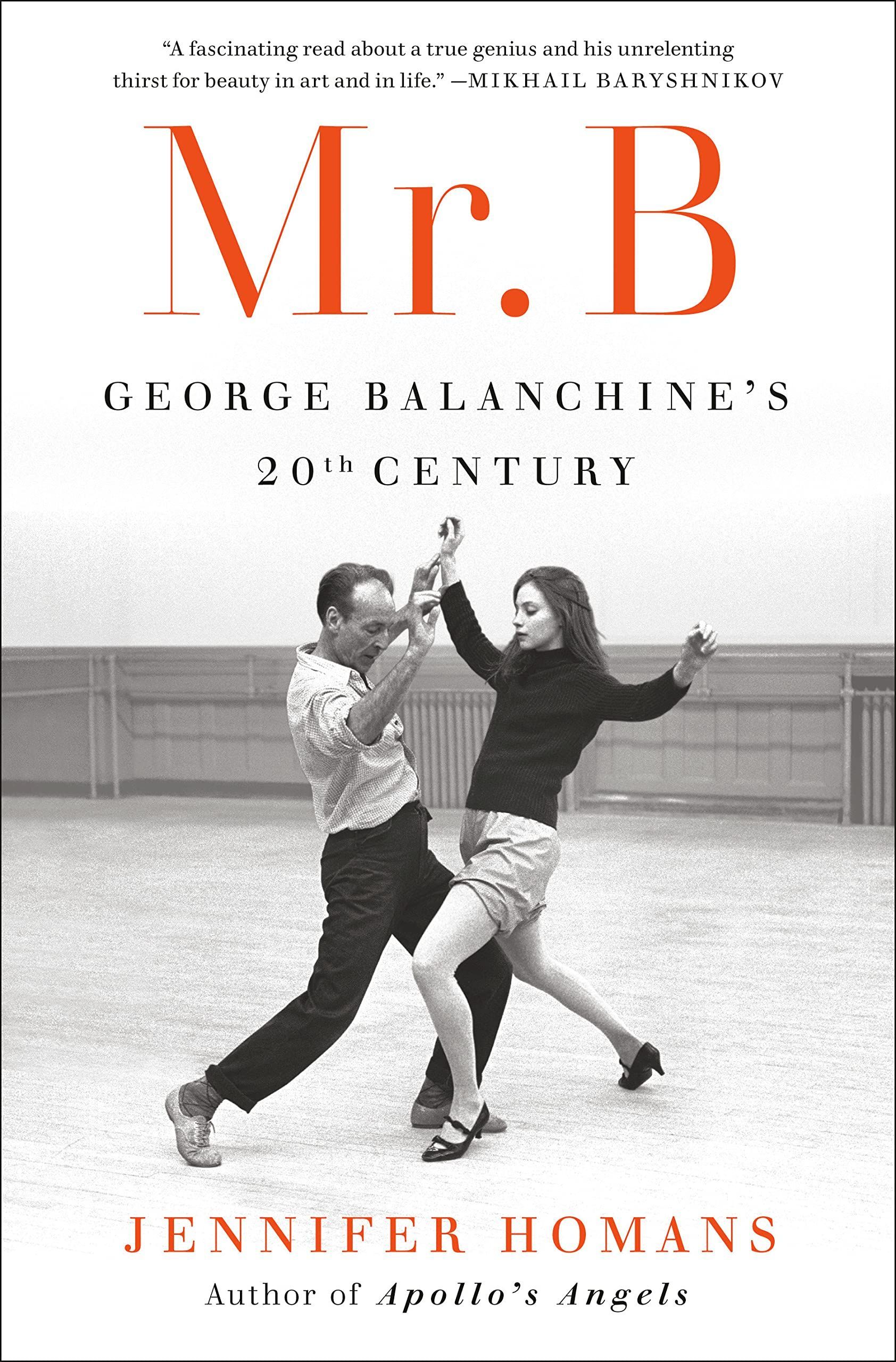

Mr. B: George Balanchine’s 20th Century by Jennifer Homans. Random House. 784 pages.

GEORGE BALANCHINE was deeply private, a man whose “mask came naturally, at birth perhaps, but was fixed over years of history and experience.” While much has been written about the celebrated choreographer (né Georgi Melitonovich Balanchivadze, 1904–83), Jennifer Homans’s Mr. B: George Balanchine’s 20th Century (2022) offers a thorough look behind the mask. The New Yorker dance critic, whose Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet (2011) is an essential reference, writes with breadth and lyricism. Her dogged research is one part of this enthralling volume, her ability to synthesize Balanchine’s complex story another, and her poetic insight into his work the capstone.

Balanchine’s parents never married; his father, Meliton, had a family before he met Maria, Balanchine’s mother. Meliton was a trained musician and a performer with a passionate nostalgia for all things Georgian—music, opera, theater, iconography. He was a dreamer and an inept businessman. Maria’s origins are murkier. She won the state lottery as a young woman, a windfall that allowed her to raise the three children she had with Meliton in a world of “fairy-tale wealth and giddy expectations.” She created a life in St. Petersburg replete with cooks, maids, and wet nurses, then purchased land in Russian-occupied Finland and built a dacha there.

For Balanchine, his past “pooled into a single sentence: ‘Oh yes, we were very happy.’” Unaware of the portents of war and revolution, little Georgi would dress in imaginary robes and pretend to be an Orthodox priest: “[T]he Orthodox faith, with its ritual beauty and music, took its given place in his mind. Belief was not a choice, it was a fact of his life.”

Homans spins remarkable threads from Balanchine’s Orthodox faith, particularly its iconography. “[I]cons use ‘inverse perspective,’” she writes.

The horizon is turned back onto the worshipper […]

Also, icons are never signed. Iconographers, like priests, are in service to God, and the whole process of making an icon, the discipline and obedience to a prescribed set of rules and rituals, is designed to remove the I from the experience.

Homans deftly applies these rules to frame Balanchine’s oeuvre.

When he was nine, Balanchine’s mother precipitously enrolled him in the Imperial Theatre School, where he boarded and was essentially cut off from family. This stark separation from everything he knew was shattering. More harrowing, however, were his teens and early twenties when the Russian Revolution erupted in St. Petersburg and he was flung from the imperial cocoon into murderous streets, trying to keep a tenuous hold on life and health while perpetually starving.

There was no future, only the fight for the next meal—sometimes resorting to cats—and for a respite from bombs and guns. During these years, Balanchine performed wherever and with whomever he could. Somehow, the Imperial Theatres, under constant attack, continued to host performances. In these formerly upscale conditions, “[t]here was little or no heat and water froze in glasses, and the orchestra sounded sharp as the instruments squeaked eerily in the frozen air. Sometimes radiators burst, covering the floor with glassy sheets of perilous ice.” And yet, Balanchine managed to cut his choreographic teeth, working with artists who were among the finest of their day. Along with her insights into iconography, Homans’s sections on the Russian Revolution provide major new insights into the wellsprings of Balanchine’s life and art.

It was not just the Russian Revolution but also the horrendous fallout from World War I that deracinated Balanchine. He joined the refugees uprooted from the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian empire and ultimately fled to Paris via Weimar Germany. There was something “finite and discrete” about the Russian part of his life, Homans writes, “sealed, like the train that had carried Lenin into Petrograd and the German boat that carried George out.” Artists who would become his closest collaborators and friends were part of the exodus: Alexandra Danilova, Nicolas Nabokov, Nathan Milstein, Varvara Karinska, André Eglevksy, and myriad others. Some were the children of émigrés or the children of earlier flights, many of them Jews.

Berlin and Paris, the two artistic centers that would affect Balanchine the most, “were exploding with new ideas and art, in part because of these displaced arrivals.” Serge Diaghilev had created the Ballets Russes in 1909, reimagining ballet “through the sheer force of his own personality and drive.” He turned ballet into an image of “Slavic ur-Russia, exotic, primitive, modern—and self-consciously styled […] ‘for export to the West.’” Many of his dancers became legends, none more so than Vaslav Nijinsky and his sister Bronislava Nijinska.

More than a decade later, Diaghilev, in declining health, met with Balanchine in Paris and recruited him to dance and choreograph. Through Diaghilev, Balanchine met Igor Stravinsky, forming an artistic pairing that would last until Stravinsky’s death in 1971. He also met the wealthy young American Lincoln Kirstein, who convinced Balanchine to come to the United States in 1933 and played every role imaginable: impresario, father confessor, donor of first and last resort, healthcare proxy, builder of ballet companies. Kirstein did anything Balanchine needed him to do, anytime.

Balanchine worked on Broadway and elsewhere. When he was in the ballet studio, he moved “ever further from ‘ballet-ballet,’ as Lincoln called it,” toward becoming “a philosophical anarchist with no interest in the traditional balletic repertory.” Balanchine also had little interest in plot.

If people know anything about Balanchine, they know that he depended on women, not just to implement his creations but also to inspire them. He loved and worshipped women in complex and distasteful ways. In the classroom, he was a magician, coaxing and flattering, creating acolytes who hung on his every word. He married Tamara Geva while still in Russia, had a “common law wife” in ballerina Alexandra Danilova when he left Russia, and subsequently married ballerinas Vera Zorina and Maria Tallchief in the United States.

His last marriage was to Tanaquil (“Tanny”) Le Clercq in 1952. Le Clercq was an international star and the first ballerina whom he had fully trained. While on tour with the company in Copenhagen, she caught polio and spent the rest of her life in a wheelchair. Balanchine stayed married to Tanny until 1969, caring for her as she recovered from polio, but left her long before their divorce. Other lovers and obsessions followed, including ballerinas Karin von Aroldingen and Suzanne Farrell. Homans does a remarkable job shedding light on these women, each a major artist in her own right.

She does this through extensive research, the description of which takes up nearly 100 pages at the end of this 784-page volume. Homans seemingly left no archive unvisited, no person uncontacted, no book unread. Her effort is truly massive. She conducted more than 200 in-person interviews, individual stories that infuse life into the descriptions of Balanchine-the-teacher and Balanchine-the-choreographer.

But the immensity of this research would be immaterial if Homans were not able to synthesize it to interpret Balanchine’s contributions to dance. Homans explains what Balanchine did and how he did it, to the extent it can be explained. Balanchine’s corpus was organic and spontaneous, rooted in a profound understanding of music and dance, a longing for a homeland that was a figment of his imagination, an adoration of women, and an ability to train his dancers to convey his vision on stage. With Mr. B, Homans unmasks how he did it.

¤

LARB Contributor

Martha Anne Toll’s debut novel, Three Muses (2022), an immersive look into the ballet world and the Holocaust, is short-listed for the Gotham Book Prize and won the Petrichor Prize for Finely Crafted Fiction. Toll is a book reviewer and author interviewer at NPR Books, The Washington Post, Pointe Magazine, Lilith Magazine, The Millions, and elsewhere. She has recently joined the board of directors of the PEN/Faulkner Foundation.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Chaos Remains: On Melissa Chadburn’s “A Tiny Upward Shove”

A debut novel from a Los Angeles labor organizer is a searing mirror on immigrant poverty.

Side by Side: On Bettijane Sills’s “Broadway, Balanchine, & Beyond: A Memoir” and Marianne Preger-Simon’s “Dancing with Merce Cunningham”

Megan Race appreciates two well-paired memoirs, “Broadway, Balanchine, and Beyond: A Memoir” and “Dancing with Merce Cunningham.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!