Records

Mauricio Gonzalez-Aranda explores “the language of the landscape” in and with respect to his hometown of Ciudad Juárez.

By Mauricio Gonzalez-ArandaOctober 6, 2021

Photograph by Genaro Cruz

¤

I IMAGINE THAT a poet working on a provisional pilot license must fly differently than most. In his small cockpit, he allows himself childish liberties. Clouds zip by and he cranes his neck back then down at shadows cast over mountains and dunes and multitudes of crowds. He wishes he could bomb them with some sense! At least then they’d look up. At solid skies marred only by his trail of line-shaped clouds — the opposite of ruled paper. He wonders what he would write.

Earthbound, I spent a lot of time looking out the window as a kid while my parents drove us around. By the time I was a teenager, I mostly remember staring up at the car headliner, taking advantage of each commute to get desperately needed sleep. So my memories of the city’s urban landscape wade back to my earliest years, when I still lived in Ciudad Juárez. Signs near and far dart across my window at variable kilometers per hour. Closest to the ground, campaign banners for Vicente Fox and municipal slogans in muted white and olive green colors jut from street lights and telephone poles; towering above them, I can always pick out the signs of at least one Del Rio corner store or Pemex gas station — the national chains; higher still stand the Fanta and canted Domino’s billboards, by far the sleekest designs. Beyond the metallic mesh, I remember the mountains.

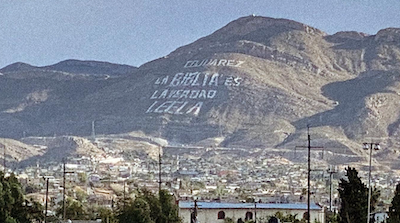

On a western mountain range, there is a sign emblazoned in white monolithic letters across one of its hills:

“LA BIBLIA ES

LA VERDAD

LEELA”

[THE BIBLE IS

THE TRUTH

READ IT]

Bible Hill, I grew up calling it. Across the border on the Texan side, the city of El Paso horseshoes itself around the Franklin Mountains, adorned by a monumental star made out of lightbulbs that appears to punctuate the city skyline when seen from across the desert outskirts. To a seatbeltless kid afforded panoramic vision from the backseat, both landmarks are visible from either city, so long as the angle is right.

I felt chastised every time my drifting eyes caught this word staring back at me through the billboard jungle; LEELA, a condescension that would remind me of my homework even when already finished. Perhaps because I felt challenged literally, I remembered protesting that the mountain should say LÉELA after one of mom’s persistent lectures on which vowel to place the acute accent that guides the stress of the word. Mom smiled as if I’d fallen into a trap that she’d been hoping to spring for a lifetime: in strict orthographic rules, capital letters should never carry the accent. But then it sounds like lela, meaning idiot, I’d retort. It was around this time that I was amassing my widest repertoire of jokes, which I’d unleash on my grandfather because he always laughed with abandon. In keeping with Galician tradition from where many classic Spanish jokes originate, I’d picked up the word lelo/lela, usually the joke’s unlucky protagonist. Reading LEELA would undoubtedly send me to an absurd fork, where depending on the completion status of my homework, I’d either feel as if the mountain were calling me a dummy for not having read the Bible, where the putative answers to the homework lay, or else I’d appropriate the word and call the mountain a lela, and my mom a lela, and the city a lela with an ever-growing smile. I don’t recall ever calling the El Paso Star a lela in this immature progression where nothing in sight was safe from my command of the word. The likely explanation is that if I was reading Bible Hill, then it was daytime, and the Star doesn’t light up until around the time the desert sunsets look like they’re bleeding. Dusk, a stricter mother might correct. I wonder, though, whether I wasn’t avoiding it, already perceiving my future impressions.

These days when I revisit home and see the El Paso Star shine, I immediately scan left for the traces of muted white on a muddled mountain. I sense aridity behind the paint.

In 1946, the “Star on the Mountain” was born when the surging El Paso Electric Company staked 459 industrial-strength light bulbs to the bedrock to construct a star that wash 459 feet long and 278 feet wide, visible from an estimated 30 miles from the ground before the curvature of the Earth hides it. Facing the sky at a 30-degree angle, as if fallen from the celestial sphere, the star’s ken reaches 100 miles from the air, inviting all airline passengers, pilots, and poets home. The hallmark quickly landed the city the moniker “Star City” in the Lone Star State. Every night, the star would be lit, and every postcard leaving El Paso soon portrayed the border as a sangria sunset obscured on the right by the Franklin Mountains and the amber star adorning it. In these images, the visible urban span of Ciudad Juárez is mistaken to be the sprawl of El Paso. In 1987, much too late to be called a response, Ciudad Juárez chose to brandish one of its mountains with its own sign, made of white stone and retouched with lime. The pastor Gerardo Bermúdez came up with the idea as part of an initiative to unite the different evangelical groups of the diocese following an ecumenical festival in the city. Presumably Pastor Bermúdez grew up normalizing the Star on the Mountain from a car’s backseat. When the moment of truth came, in his mind it was perfectly logical to suggest another landmark on a mountain.

Ever in the distance, my closest relation to Bible Hill was the nanny we had growing up. As is common in Mexican culture, my family paid a woman to come clean our home and double as a babysitter most days of the week. Our parents were very clear to remind us not to be like other “insensitive” families that use the term “servant” when referring to them and instead to say “the woman of the house.” Even then I could detect how the formality, the awkwardness of the phrase that sounds more like a novel’s title, repressed the class difference. One day when she had just arrived, I called her by her name, “Silvia, where do you live?” “Um…” She took some seconds to formulate an answer for me, too young to know city neighborhoods or streets beyond whether they were close to a friend’s house: “I live over there by the hill with the verse.” I followed her gesture to the horizon and saw tiny houses made of wood, tin, and untreated cement that crept up the foot of the mountain. Another pin appeared on my mental map, expanding to the outer city limits. I fabricated a morning routine for Silvia from the little I knew about her life. She’d wake up her two kids, in a hurry for some reason, leave them a covered pan of scrambled eggs and ham on the table, and walk out of her tin or wooden house wearing her usual oversized T-shirt, bleach-white. (Her shirts — more a credential than a uniform — somehow always remained pristine throughout the day.) I knew that in order to make it to our home on time she woke up before dawn, but the image in my mind is of her under the sun as a white speck below white letters descending on foot from the mountains to catch the bus. Later I’d learn in school what appearances made painfully clear. These were the slums. I refused to consider Silvia as being part of the slums, rather happening to be living in them — above them, at the foot of the Bible verse. I assumed she’d read the Bible and that she knew it by heart.

I was born into a landscape with a mountain referencing the Bible and another, a star, absorbing their symbols. Had I never left home, had I become a priest, I might have brandished my own mountain and considered both my creativity and the creation a work of providence. For who else would ever scan the horizons and from their seat claim a sight as their own? It’s ironic that until recently I didn’t know that Bible Hill’s real name is Cerro Bola (Ball Hill); a common expression in Mexico for “who knows” is sepa la bola, which translates to “don’t look at me, try that balled up group of people.” In my privileged view, I never felt the need to look it up.

¤

I only recently revisited Bible Hill online. The tangential whim came after a friend sent me an article about the Chilean poet Raúl Zurita, who has quite literally left his mark on this Earth by tracing poems on its surface and sky. The septuagenarian is scheduled to unveil a new work. The news first sent me down a rabbit hole of retrospective articles.

In the 1980s, Zurita took to the skies. He and members of the artist group CADA flew six airplanes over the poor neighborhoods of Santiago in 1981. From the planes’ hatches rained down 400,000 flyers, a reminder of the 1973 bombardment of the government palace that let Pinochet come into power. The printed message, however, was inspirational: “We are artists, but every [one] who works for the enlargement — even if only a mental one — of his living spaces is an artist.” One can imagine at least one Chilean snatching a flyer falling from the sky and wondering if this is why it’s called a flyer (volante) — an honest attempt at enlarging the mind.

A year later, Zurita and the gang rented five airplanes, this time in New York City, and they streamed the skies with a poem in Spanish titled “Anteparadise.” Variations of what God meant to him, such as “My God is hunger” or “My God is Ghetto,” repeated across lines seven to nine kilometers long. One can imagine the struggling class reading the blue skies in solidarity until the white contrail thinned out. Then in 1993, the year I was born, Zurita hit the ground, hard. The poet bulldozed onto the northern desert of Chile the Spanish phrase “No shame nor fear” that spans over three kilometers at the sandy foot of a mountain range, visible to this day. One can imagine virtually no one being able to read this one until Google Earth made it available to everyone virtually.

Zurita once explained that, faced with a morphing political landscape, the prosody of his Hispanic predecessors, the likes of Octavio Paz, had grown stale, and a new language that transcended was necessary. The language of the landscape, perhaps.

A quarter of a century later, after having explored the skies, grounds, and, in some smaller exhibitions, water, Zurita’s latest project to type out a poem on the ocean cliffs in northern Chile suggests a new phase marked by the tense boundary between elements. His compressed life distends my mind to the rock-strewn scale of kilometers. Bible Hill materializes. I realize its sign has never been normal.

Up against the poetry of Zurita’s terrestrial vandalisms, I find myself annoyed at the unoriginality of my fellow Juarenses. I expect a certain boldness to follow the arrogant decision to enslave a mountain to a message: a passionate rile, an enlightening observation, a call to be answered, not unlike Zurita’s as he decides with his poems to lob stones at the establishment, to paraphrase my friend’s text. And in this invitation to read the Bible, I find the wrong kind of gall. Instead of laying down a personal truism, the intrepid author chose to reference a dense body of work that has already fought its own crusades. To quote a proverb would have been at least some expression of curation. From a prosodic perspective, the enjambment of the second line, highlighting “the truth,” feels especially outdated (some might argue “relevant”) in a modern era that has been called “post-truth.” The conservative message in our progressive times embarrassed me slightly, an irrational fear of being held accountable when identifying as Juárez-born. Zurita, too, alludes to the Christian God, nearly always, but he illustrates God as a humanist, one aware of the grief and pain in life, pregnant with the audience’s life experiences.

And the last line, the odd imperative which seems appended out of insecurity, feels out of place.

¤

Bible Hill may be the largest invitation, or should I say command, in the world to read the Bible, spanning 30,000 square meters, with each letter measuring up to 50 meters in length. Gabriel Andavazo, the current pastor in charge of the sign’s conservation, attested to local press that he’s encountered many people in his years who have decided to open up a Bible and found God due to the sign. (No reporter quipped back whether this was “a sign.”) Notwithstanding the persistent objections by local environmentalists who claim that the mountain’s fauna is endangered by the lime, Pastor Andavazo leads a group of volunteers through the biennial process of retouching the weathered letters with a new coat of paint and picking up the surrounding trash. He retorts that the trash they clear would certainly endanger the arid vegetation and wildlife. Last round, nearly 2,000 Juarenses came together for the sign’s maintenance. Perhaps the back-breaking task proved to be a reality check for these volunteers, too, that this sign was by no means average. In 2018, they sent a petition to Guinness World Records, applying for not one, but four titles: the largest invitation in the world to read the Bible, the sign that covers the largest area, the sign with the largest letters in the world, and the sign hand-painted by the largest number of people in the world. If any of these are approved, a mailed certificate from London will deem Bible Hill in Ciudad Juárez to be “officially amazing.”

This isn’t the first time that Ciudad Juárez has attempted to land on the Guinness World Record book, which I associate strictly with scholastic book fairs that my teachers and parents forced me to attend. The book sat on display atop the stacks of unadorned best sellers, every year with a new gaudy 3D book cover design that reeled in the kids, suggesting a trove of entertainment all the other flat books lacked. Our teachers reluctantly acknowledged the lurid book as at-least-he’s-reading literature. I’d flip through record after record, wondering who this freak from Ireland was, how such a skilled person could live in Missouri. A photo of the man with the longest nails, which he kept protected normally behind a veil of silk that dragged to the ground, remains seared into my brain. At times when the record seemed within my realm of plausibility, I’d try out my name in place of its holder. Fastest marathon, or anything Olympian, was automatically cool. Fastest marathon while carrying a bicycle was also acceptable; I liked the implication of a second gear on your back, untapped potential.

I remember trying to come up with a new record to quickly get on the record books. More often than not, it would fail to meet the criteria set by Guinness: a Guinness World Record has to be (1) measurable, (2) breakable, (3) standardizable, (4) verifiable, (5) based on one variable, and (6) the best in the world. For example, you are unlikely to have a world record for the most anti-establishment pamphlets scattered on a city from six airplanes piloted by poets because how do you count the strewn pamphlets (criterion four), and more importantly, how do you determine who a poet is (criterion one)? In my fantasies, I’d often get tripped up by number six, which explains that if the record you suggest is new, Guinness will set a challenging minimum to break. I’d always envision an insurmountable minimum and myself as pathetically ill-prepared.

I imagine myself flipping past the individual records and stumbling upon the chapter on size. A banner across the top third of the page features a photograph of Bible Hill and next to it “Largest Sign in the World” followed by three titles, in smaller font and indented, enumerating the additional honorifics. I wonder whether I’d project myself into the image, living by Silvia’s house in this exotic mountain city, reading its glyphs every day. I realize that as a kid I’d think of these records as boring and flip right past them, so what kind of reader would I need to be then? My fantasy is doubly ruined when I imagine an editor sending back her revisions to the Guinness team. She notes that devoting 30 percent of the Arch-A-sized page to a photograph of a mountain that promotes the Bible would not be “very PC.” The more progressive choice would be a picture of the Largest Sign Language Lesson. After all, she notes, a thumbnail of Ciudad Juárez can always be reintroduced under the “Food and Drink” chapter.

Ciudad Juárez unofficially entered the race for a culinary Guinness World Record in 2015 when it announced that it would be attempting the largest burrito ever made. In a debate that I did not know existed about the origins of the burrito, history buffs claim Ciudad Juárez to be the birthplace of the Mexican dish that has now colonized Tex-Mex cuisine. Legend has it that in the 1910s, while the mythical Pancho Villa rode on horseback across the northern state of Chihuahua riling up insurgents for the Mexican Revolution, a food vendor in Ciudad Juárez rode a donkey and sold lunches warmly wrapped in a tortilla. Burrito, a Spanish diminutive for donkey, quickly became the term for the equine dish. Seizing the urgency of the topic, some 100 years later an event was set up in Ciudad Juárez to break the world record of 2.4 kilometers for the largest burrito, held by another Mexican city, and bring the title to its rightful home. When the event was cancelled, the organizer cited insufficient funds from the municipality and sponsors as well as a breach of contract by the head chef hired for the event. Said chef denied the claims on Facebook, adding even that he had no knowledge of the event in question.

Not to be denied, Ciudad Juárez tried their hands at a different feat in August 2017. Five hundred people gathered to break the record for the biggest carne asada (Mexican grilled steak). Previously, Kansas City, Missouri, had recorded 336 simultaneous regular, non-carne asada grillers, among them surely the Missourian virtuoso from my childhood readings. After chucking through six tons of beef, two tons of charcoal, and 1.5 tons of corn tortillas, the Guinness official who had been flown in to monitor the event tallied 394 simultaneous grillers. He announced (on a soapbox and with a megaphone, in my mind) that while the record books have an entry for most tacos served, there had been no precedent for the most simultaneous grillers of carne asada. He would recommend to the London headquarters that a new category be created and its record decreed. Here I am forced to infer (the literature available on this historic event is sparse at best) that Kansas City’s previous number remained as its own record, but it served as the challenging minimum for the new category (criterion six). A month later, for the first time ever, a mailed certificate declared Ciudad Juárez to be “officially amazing.”

I keep on claiming that Ciudad Juárez was aiming for a record, as if its citizens were a single amoebic entity — a flock of birds chain reacting to course corrections or predators on their flank. In reality, the efforts have been launched by a pastor, or an entrepreneur, or an alleged chef. And no amount of Facebook events will ever unite a city to the point of single-mindedness. But tragedy flanks Ciudad Juárez.

I remember reading in 2008 the statistic that Ciudad Juárez was now the most dangerous city in the world, including Baghdad during the Iraq War. The drug war between the Sinaloa and Juárez cartels was at its peak. Another memory that sticks out is an image of the Ciudad Juárez newspaper, El Diario, reading in smack bold letters “8 Die on Average” and below it a roll of eight portraits of yesterday’s victims, a banner covering a third of the B3-sized page. I remember thinking that in the strictest of orthographic styles, a number should not begin a sentence, but newspapers were allowed this and many other concessions to save space. I read these safe at home in El Paso, which at the time was the fourth safest city in the United States. My dad was still commuting across the border to work, developing insomnia and mild PTSD. Silvia had long stopped coming over. A slew of statistics began to clobber the community, and I remember using the word “infamous” for the first time. “But we escaped the worst of it,” I often summarize at dinners and parties in Denmark, where I now live, to polite Europeans who attempt to relate. Sometimes when I work my way forward and say I work in the film business, I get asked how I liked the film Sicario by Quebecer fiction director Denis Villeneuve.

Before the cartel wars, there were the femicides in Ciudad Juárez. Hundreds of women have been killed in horrific ways in a series of unrelated crimes that date back to 1993, the year of “no shame nor fear,” the year of my birth. The culprit is every man in Ciudad Juárez — a product of a cultural, systemic misogyny, neatly described as machismo. White crosses in memory of the women, often disappeared, sprung up across the desert outskirts of the city and along highway shoulders. Just as with Bible Hill, growing up I didn’t consider the tombs atypical; I normalized them within the archetype of any other desert city and within the archetype of crime. Why wouldn’t there be women killed where there is crime? (Why wouldn’t there be Bible readers where there is an invitation?) The usual reference for this one, if at a party with well-read guests, is Roberto Bolaño’s tome 2666, which is tastefully set in the fictional border city of Santa Teresa, which mirrors Ciudad Juárez’s atmosphere in the ’90s. If at a party with film industry folk, it’s Julien Élie’s documentary masterpiece Dark Suns.

Pick your lead, pick your decade, and Ciudad Juárez was deplorable. Homicidal or festive predators on all flanks. Terrorized citizens filled with fear or shame looked for hope on the horizon, if the angle was right.

The journey toward “officially amazing” that began during the cartel wars was at first a coping mechanism, an attempt to express a voice by a community terrorized by gangs and sullied by the media. Against the suggested curfews (drive-by shootings and turf wars had long stopped leaving civilians “out of it”), families and friends pushed their life outside again, met, even demonstrated and preached solidarity. Teenagers rebelled against friends’ parents offering their backyards on Saturday nights, went out clubbing instead. Every day, along with fear, camaraderie was palpable. General distrust for politicians was suspended; they were allowed to make uplifting promises. Nonprofits promoting, not opposing, surged. The slogan “Amor por Juárez” (Love for Juárez) and its logo, a heart clenched by a hand making a peace sign, replaced political banners on light posts and soon dotted the landscape below the dilapidated Fanta and Domino’s tier. Adorned rear windshields began sporting the logo sticker. Children began to look out car windows again, and you noticed they’d been missing. A movement to reinvent the city’s image erupted in every citizen. Citizens who wanted to reach laudable, measurable attributes through individual effort or organized work. Citizens who had surely been to scholastic book fairs growing up.

¤

After hopscotching my way across to Copenhagen, I’ve begun to rekindle habits from my past. I started swimming again, wanting to relive the glory days of my adolescence when I was a serious swimmer. Maybe even the fastest swimmer in certain events on either side of the border. As I began to go through the routine of swimming several days a week, the strain on my body dislodged memories of my past — a different sort of muscle memory. Somnolence reminded me of the long car rides of my teenage years. Back then I swam twice a day, before dawn and after school. Always sleep deprived, mom transformed the backseat into a provisional bed, permanently. God was Glory, God was Bed, God was Sleep. I signed up for a Danish Masters competition (an international league geared toward I-used-to-swim old-timers) after only a handful of times back in the water, eager to race. I wondered whether I could break a Danish record in the category of ages 25 to 29 and looked them up. I imagined how González-Aranda would look next to all the Nielsens, Sørensens, and Andersens. How it would look to whom?

The idea of a record is predicated on the assumption that someone will look it up. For the Olympian, the glory is assured; Olympians imagine their endless competitors and fans as clenching a fist, out of anger or excitement, yelling their names. More niche events may require greater trust in the avid fanbase. The chef of the largest burrito imagines history buffs as they wrestle hysterically and point to the city where it was cooked as further evidence of the dish’s roots. Zurita, a great poet outright, must have also found appeal in the thought of future audiences stumbling onto an aerial shot of the Chilean desert and exclaiming at the size of the bulldozed line, wondering if it is the largest of its kind. My record — a Danish record for retired swimmers aged 25 to 29 who were once on the edge of glory and long for its taste — was so foreign that my subconscious was no longer able to picture kid-me accessing the information, judging its coolness. I struggled to imagine an earnest adult looking up the same information, even less admiring it. It was easier to picture a vague, probably hellbent social worker in the Danish government running a background check on my immigration papers and learning about the record. His brow would furrow, annoyed that a foreigner had stolen the title from “one of theirs.” A small victory for the immigrant. Absurd. My mind fabricated the farce in less than a second rather than admit that the record might have no external validation. A record meaningful only to me meant nothing.

It seems to me that societies inured to competition, such as the United States and Mexico in my experience, are affected by the gross misrepresentation of the number of people participating in it. There exist the real participants who are striving to the top in their respective careers, activities, or financial goals. Then there are those usually in the middle who are passive and long ago stopped trying to climb for whatever reason, and if a miraculous opportunity to rise higher presented itself, they would seize it. These effectively no longer participate but are not opposed to the lifestyle, so they serve to bulk up the competition pool. And finally there are those to whom competition does not apply because the nature of their careers or activities are not competitive. They become navel-gazing, move out to suburbia perhaps, focus on their families. Yet the society as a total is said to be competitive. The concept of winning a competition, meaning recognition, is scaled by the magnitude of all three groups, even though only a few care. Never mind the communities that eschew the American Dream or entire countries like Denmark which preach egalitarianism to an irritating degree. For the few who care, the masses strive.

People brought up in competitive environments will find it hard to part ways with its value system. After all, there exists a thrill in competition. Would I swim in a pool with one lane line? Perhaps. If there were still a clock. Does this mean that my pleasure stems from self-improvement and self-actualization? A desire to see the full extent of what I’m capable of? To expend the energy I feel tensed up in my muscles. To crystallize a thought full of promise.

My lifestyle remains caught in a value system based on competition. The leap to a full renouncement remains too big. I pity a future where I make the move out of exhaustion or defeat. I presuppose that a deliberate change requires an enlarged mind I yet lack, and I try to patch my immaturity with poetics. If my current self is looking up and chasing a win granted by the masses, then my future self must be on a vantage point looking around and chasing the masses to communicate a message from within. Perhaps,

A city meaningful only to itself has meaning.

A mountain forgotten has its name.

My horizon is earthbound.

[Una ciudad con significado sólo para sí tiene significado.

Una montaña olvidada tiene su nombre.

Mi horizonte está en la tierra.]

My future self will have borrowed from Zurita’s temerity, a man who refused to become either cliché of the poet who wants to fly or the poet who trashes the establishment, and fused them both on printed messages. A similar impertinence feels essential for Ciudad Juárez.

Ciudad Juárez is right in principle to fight violence with a diversion to reinvent itself. Ignoring it would abide it. And any action that works toward eradicating violence resets the city to a cavernous present, the null state of a formerly active zone. So the city works toward overshadowing its history with brilliance. The strategy: Flood the media with tawdry trivia. I support — like hometown politicians allowed to utter felicitous promises — a vibrant culture that celebrates its heritage, even if it’s around the burrito.

My indignation at discovering that Bible Hill was in line for a record is rooted in the exploitation. The sign is prosaic, yes. Members of Ciudad Juárez took to the mountains like bandits and whitewashed it with their version of the truth. They were poets — bad ones. But it’s precious because it was a cavalier product of the culture and then a reference point for those who lived nearby. That Guinness arbitrates makes me question why we need a corporate standard — or even the more generic Western standard of excellence — as the vehicle for our image. When the community looked for a practical way to convert the solidarity accrued in the “Amor por Juárez” movement, it tacitly summoned Guinness, the stub from childhood, as their emblem of success. The spirit twiddles its thumbs for years as the record application is processed, awaiting the overnight news that it is amazing. The plan strikes me as naïve to a fault, like a stunted thought that could benefit from raining flyers demanding the enlargement of the mind. Flyers saying forget the records, forget the statistics, forget winning, forget swimming, a limping community does not need to maximize its assets, rally in the mountains, pastors and sicarios and women-of-no-house alike, here’s some chalk, here’s some stone!

If we’re a city of born vandals, shouldn’t we be more brazen than Zurita, a converted vandal? Foolishly I want to meet party guests, shake their hand, see their eyes widen, Oh you’re from that city where poets graffiti on the mountains, firm grip, we call them Juarenses.

¤

There was one more Guinness Record in Ciudad Juárez’s history. Largest Astronomy Class. On October 14, 2011, on the sand dunes of Samalayuca at the city limits, over 400 Juarenses pointed telescopes and binoculars at the sky, breaking China’s mark of 250. Four years later, the race had ballooned to the next order of magnitude. Ciudad Juárez unofficially retook the title with 1,168 attendants from Australia, only to lose it again.

When telescopes and binoculars and any optic in between gather in one spot, the stargazers tallied must be verified by Guinness in order to become officially amazing. Not required by the record, however, is for all to be gazing at the same point in the sky, or even at the sky for that matter. It is assumed their sights are set high. Yet they could be pointed at the horizon, a distant Star on the Mountain visible without a lens. They could be scanning the skies for raining flyers rather than stars. Or pointed at the desert dunes, without fear or shame, without a record, unofficial, absolutely ordinary.

¤

Mauricio Gonzalez-Aranda is a Mexican American documentary director living in Copenhagen, Denmark. His debut documentary, A Word for Human, about the Royal Danish Library, premiered in CPH:DOX 2019. Find him at mauriciogonzalezaranda.com.

LARB Contributor

Born in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, and later raised in El Paso, Texas, Mauricio is a documentary director living in Copenhagen, Denmark. His debut documentary, A Word for Human, about the Royal Danish Library, premiered in CPH:DOX 2019. He graduated in 2015 from Princeton University with a bachelor’s in Physics. Find him at mauriciogonzalezaranda.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Justice for the “Restless Dead”

Adela Pineda Franco contemplates “The Restless Dead,” the recently published book by Cristina Rivera Garza.

The Myth of Mestizaje

A celebrated Mexican anthropologist explodes one of his nation’s founding myths.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!