Reading in Slow Motion

On the sentences of Shakespeare and Anne Boyer, Roland Barthes and Joan Didion.

By Katie da Cunha LewinDecember 14, 2020

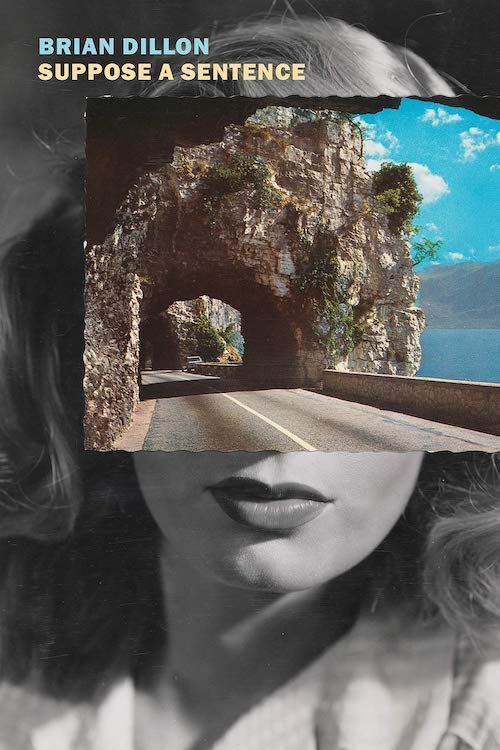

Suppose a Sentence by Brian Dillon. New York Review Books. 232 pages.

WHEN I TEACH academic writing, I often direct students to the paragraph. I want them to make paragraphs an integral part of their thinking and planning, to consider the focus, arguments, and meanings of each. I’ve noticed that students can sometimes be so worried about the content of their overall arguments that they forget that their ideas must be structured into paragraphs. As they learn how to negotiate the larger problem of getting ideas to stay in shape, the trifling problem of the even smaller unit of writing, the sentence, is sometimes far down the list of their concerns. In fact, for some, it seems that the sentence is so simple, so obvious, as to become invisible.

I’m not pulling rank on my students: I too have been guilty of overlooking the sentence. Sometimes, when struggling to connect two ideas together in writing, I balk and type frantically “sentence needed here.” This vague directive, often emphasized in bold, seems to me to have something of the schoolteacher about it: I am hoping to scare myself into productivity and, hopefully, creativity. I’ll let my fingers walk across the keyboard for a while, and wonder when this produces results. I’m hoping some of my sentences will do my thinking for me, as if they are otherworldly beings with minds of their own.

The writer, essayist, and professor Brian Dillon is a superb reader of sentences. His new book, Suppose a Sentence, is composed of essays of varying length, each focused on a single sentence from the works of 27 writers, ranging from Shakespeare to Anne Boyer. Dillon does not tout these as perfect examples of what sentences should do or be, but includes them because of his own affinity and admiration: “I knew at once that I had no general theory of the sentence, no prescriptive attitude towards the sentence, nor aspired to write its history. If I must (and I felt I must) write about my relationship with sentences, I would have to follow my instinct for the particular.” The book is a representative collection of sentences that have stuck with him, moved him, and in assembling it in this way, Dillon has eschewed what is sometimes called critical distance but which in reality is often a rejection of the ickiness of personal feeling or appreciation.

As Rita Felski writes in Hooked: Art and Attachment (2020), the question of why a preference for critical distance has endured has to do with the sense that reading out of love — out of what she terms “attachment” — is simply bad reading. Attachment, she suggests, “is often outsourced to others — naïve readers, gullible consumers, small-town patriots, too-needy lovers — and treated as a cause for concern, a regrettable, if common, human software malfunction.” But Dillon demonstrates that reading out of love, lingering over cherished sentences, can draw out an astonishing wealth of material. These sentences are like old friends, with the constant ability to still surprise, even after many years of knowing them. He explains that he wrote “with my nose to the page […] wrote from one fragment to the next,” and we get a sense of this closeness, this attention, throughout. In these days of short, bite-sized reviews and shrinking spaces for a longform response to new releases, it is remarkable that Dillon (and his publishers) have given so much space to such detailed criticism.

Dillon’s essays vary in length and focus, sometimes producing lengthy explorations, such as his piece on Barthes, and sometimes briefer ones, as in his response to Anne Carson. Dillon also has an eye for the strange little choices others may overlook: he gives a penetrating reading of an “and” in a Clare-Louise Bennett story, for example (“each ‘and’ is an exclamation, not a statement of proximity or progress. And gets us to a place beyond likely partygoer behavior, into a realm of pure conjecture and even fantasy”), and he meditates on Elizabeth Hardwick’s use of a comma that strangely transforms the meaning of one of her sentences (“He died, grotesquely like Valentino, with mysterious, weeping women at his bedside”). Dillon moves across forms of writing, mostly lifting his chosen sentences from nonfiction works, though there is a smattering of fiction and one line from a translation.

So often writing is presented as if it emerged from the writer fully formed, without the intervention or guidance of anyone else, but throughout the collection Dillon is attentive to the editing process. In his essay on Joan Didion, for example, he selects an early caption she wrote for a 1965 article in Vogue, which describes the interior of Dennis Hopper’s house: “Opposite, above. All through the house, color, verve, improvised treasures in happy but anomalous coexistence.” This is a curious choice, particularly for a writer of such vast output, and thus so many sentences from which to choose. But Dillon explains how, through this sentence and many others like it that she wrote during her tenure at Vogue, Didion became the author we know, thanks partly to the merciless work of associate editor Allene Talmey. As Didion herself explained, “Every day I would go into [Talmey’s] office with eight lines of copy or a caption or something. She would sit there and mark it up with a pencil and get very angry about extra words, about verbs not working.” But Dillon also notices, through some scholarly sleuthing, that his chosen sentence later morphed from this early version to a streamlined one in an essay from 1978, suggesting Didion’s unending editing process, not only her desire to whittle away at the unnecessary but also to find more harmonious combinations of words.

Dillon is a great appreciator of that vexing descriptor, style, even when it is awkward or clunky, as seen in his essay on Robert Smithson. Smithson’s sentence, “Noon-day sun cinema-ized the site, turning the bridge and the river into an over-exposed picture,” Dillon explains, “insists on [its] main conceit,” an image of an image of an image. It also echoes Smithson’s sculptures, becoming “a sentence as container for the rubble of meaning”; its awkwardness becomes a model of making art. I like these inclusions; I like to see writers not always producing elegance — after all, not all thoughts are elegant. Dillon generally seems to be drawn to ambiguities, odd word choices, confusing pairings: “[I]sn’t this also a slightly confusing phrase?” he asks about Elizabeth Bowen; “Is it not in the nature of a flash that it should flash rather than quiver?” he wonders in his piece on John Ruskin. Many of the sentences prompt more questions than Dillon could ever answer. These moments are united by the idea that so much of writing is the product of fortuitous accidents: an overzealous editor could have changed something, a translator could have done something else, or the writer could have decided against that extra syllable, but they didn’t, and here is what remains.

Some criticism, usually written by a certain kind of worryingly self-assured man, seems to seek total control over its materials; it says, “I am smart, of course, but that’s not really my subject here.” But of course, that ego rears its head often, name-dropping gratuitously, including references for their own sake, not for their illuminative value. I’ve found myself worrying, in my own reviews, if I should be emulating that man I read so often, who speaks in a voice of total authority. But I can’t do it. I cannot pretend that, as a critic, I can read definitively, holding the text in place with the pin of my attention. And Dillon, too, is looking for some other mode than mastery: “I wanted sentences that would open under my gaze,” he writes, “not preserve or project their perfection.” He does not fix these sentences in place, but inspects them from all angles, allowing them to shift and glitter through his readings. Nonetheless, he stays near to his writers, not to control but to accompany. It is a way of showing generosity, and care too — as if to say that both writing and reading need adequate time. At one point, as an aside in his essay on Susan Sontag, Dillon addresses this topic: “[I]s this what I’ve been trying to do with all these sentences? To read them in slow motion? Would reading in slow motion make you more alert, or more stupid?” This form of scrutiny exposes the strange chemical process that underscores all writing.

All of which reminds me of a scientist acquaintance, who once described her PhD dissertation as follows: “My focus is on what happens when you mix chemicals together. Like what happens with baking. I want to see if you can wrench the original ingredients apart again, or if they have become only a brand-new thing.” This is a fine description of the tightrope walk of all good criticism: should it seek to identify that original mix of chemicals, inspecting them one by one, or should it analyze and admire the finished product? Dillon, in this collection, keeps his eyes on both: the sentence, as a beautiful object, is both one thing and many things, an extraordinary, almost unknowable, composition of parts.

¤

LARB Contributor

Katie da Cunha Lewin is a writer and lecturer in English at Coventry University. She is the co-editor of Don DeLillo: Contemporary Critical Perspectives, published by Bloomsbury in 2018. Her essays and reviews have been published widely. She is currently working on a book about writing rooms.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Politics of Rediscovery

By always relegating work by women artists to the zone of the neglected or forgotten, we risk only understanding them in this way.

Roland Barthes and the Urgency of Nuance

Philip Sayers on the difficulty and importance of recovering Roland Barthes’s engagement of the neutral in our political moment.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!