“Pretty Big Once”: W. R. Burnett’s Cynical Americana

W. R. Burnett’s multifarious fiction exposed the fatal emptiness of American ambition.

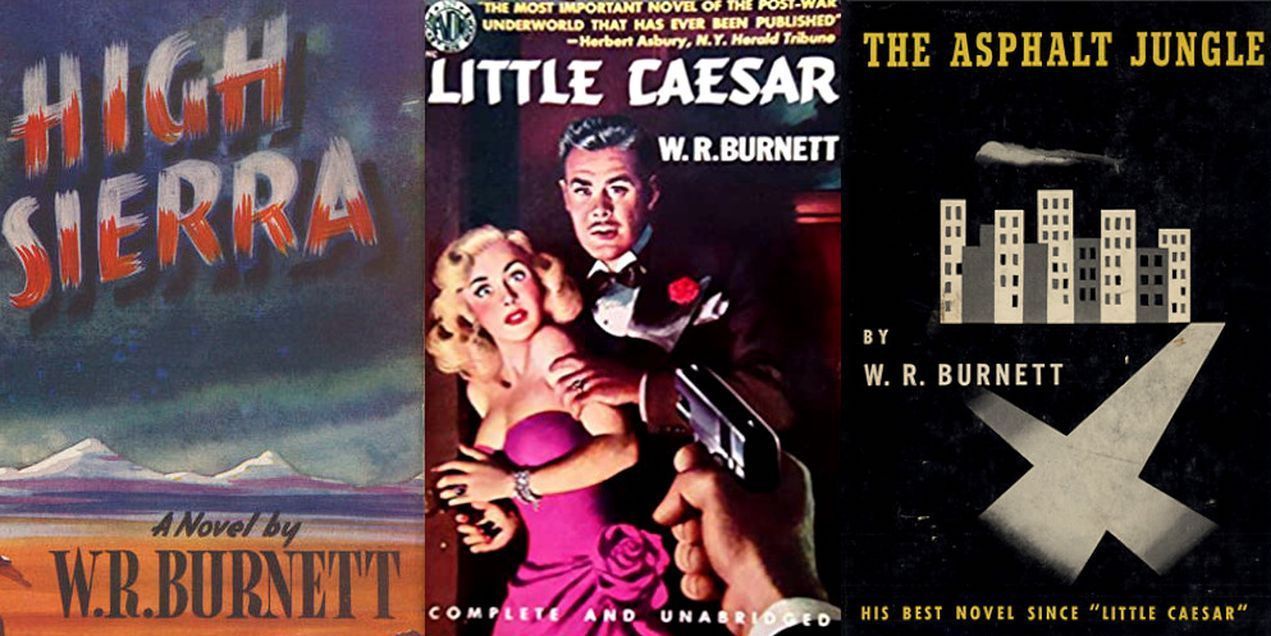

APRIL 25 OF THIS YEAR marked the 40th anniversary of the death of W. R. Burnett (1899–1982), an author whose legacy is synonymous with American crime fiction. Burnett invented the modern gangster novel with Little Caesar (1929) and twice more pushed the genre to new heights with High Sierra (1940) and The Asphalt Jungle (1949). In Hollywood, he wrote dialogue for Scarface (1932) and screenplays for the adaptation of High Sierra (1941), starring Bogart, and for Graham Greene’s This Gun for Hire (1942). But while these works have largely come to define Burnett’s legacy, crime writing represents only a small portion of his literary output, much of which has lingered out of print for half a century or longer. Revisiting his career allows us to see how it was not confined to a handful of famous mysteries but amounted to a more personal body of work that crosses genre lines.

In the bibliography included in his novel of Midwestern politics, King Cole (1936), Burnett’s output is described as “Americana,” with three subsections: “Night Life,” “Midwest,” and “Southwest.” While he would later add other geographical locations (such as Los Angeles, Alaska, and Ireland), this early-career schema accurately identifies overarching regional and topical commonalities in much of Burnett’s work. There is, however, a still stronger theme that binds his oeuvre together: the black hole — and blacker heart — of ambition. “I was pretty big once,” says disbarred doctor–turned-junkie Doc Ganson in Nobody Lives Forever (1943); aging pickpocket Pop Gruber retorts, “Once doesn’t count.” From the heartland to the blood-soaked streets of Chicago to the Sierra Nevada mountains, W. R. Burnett refracted the myth of American prosperity through the nihilistic lens of noir, revealing a world built on empty hopes and false promises.

¤

Born on Thanksgiving weekend, 1899, in Springfield, Ohio, to Theodore and Emily Burnett, William Riley was named after his grandfather, a former mayor of Columbus. Political service would continue to run in the family for generations, with Theodore later working for Governor James Cox. Young William Riley, too, would one day work in politics, but only after abandoning an early interest in sports. “I played freshman football at Ohio State until I realized I was out of my class,” Burnett told Ken Mate and Pat McGilligan in the January/February 1983 issue of Film Comment. “I quit school and got married at twenty-one.” After dropping out, Burnett followed in his father’s footsteps, working for Cox on his failed presidential bid and then as a statistician for the Department of Industrial Relations for the State of Ohio.

Spending his life in government, however, was not in Burnett’s future. During the early 1920s, he set his eyes on a literary career. “I got interested in reading and writing,” he reminisced to Mate and McGilligan. “I read everything I could get my hands on. Absolutely indiscriminately. I’d read Joseph Conrad on the one hand and The Amateur Gentleman [by Jeffrey Farnol] on the other. I didn’t know good from bad. Little by little I made up my taste.”

Burnett’s early work experiences, however, would leave a lasting impression on him, forming the foundation of his literary worldview. “I got interested in writing about crime because of things I was exposed to in my boyhood,” Burnett told Cecil Smith in a September 19, 1954, Los Angeles Times profile. “Not criminals — politicians. I cut my teeth on politics. […] I knew from my earliest memory of how politics and crime were interwoven.”

After failing to sell several novels, Burnett hit upon a new concept that would take him away from his stomping grounds of Ohio and skyrocket him to literary fame. “My idea for [Little] Caesar was to write a story from the viewpoint of a gangster, see the world through his eyes,” Burnett remembered to Cecil Smith.

To do this, I had to know gangsters. I went to Chicago — this was the 20s when Chicago was like Hollywood, gangsters were the stars and money flowed like water. A newspaper reporter named Ryan took me around and introduced me to some of the people. One was a pay-off man for a big North Side gang. I moved into his hotel. He was suspicious of me at first but when I told him I was an author and wanted to write a book he laughed at me and said I was a fool and told me everything. He gave me Caesar.

Published in 1929, Little Caesar not only set the standard for a century of gangster novels to come but also introduced what would become the archetypal Burnett protagonist: a man driven by ambition who pursues his goals with suicidal determination. Cesare Bandello, a.k.a. Rico, is a lieutenant in Sam Vettori’s mob, but he aspires to be the top gangster in Chicago. When a restaurant holdup goes bad on New Year’s Eve, police officer Captain Courtney is murdered by Rico, against orders from Vettori that there should be no killing. When one of Vettori’s men tries to turn himself in to the police, Rico sets off on a violent path that gives him control of Vettori’s mob but makes him a lot of enemies along the way. Rico’s downfall should come as no surprise — he’s an underworld Icarus — and the novel’s famous last line captures the futility faced by many of Burnett’s antiheroes: “Mother of God, is this the end of Rico?”

Like Rico himself, Burnett shot to the top of his field. Hollywood beckoned, so Burnett left Chicago for Tinseltown, where he wrote or co-wrote such crime films as The Finger Points (1931), The Beast of the City (1932), and Scarface (1932). Cinema, however, was not Burnett’s passion. “I was actually subsidizing myself so I could write novels,” he explained to Mate and McGilligan. “Films I never took seriously as an artistic endeavor, but I always did the best possible work I could do; I never brushed it off or anything.”

Though he is closely associated with the crime genre, Burnett didn’t spring from the pulp trenches like his contemporaries Dashiell Hammett and Erle Stanley Gardner. “The mystery novel never attracted me,” Burnett said to Mate and McGilligan. “It’s just a trick. Once you find out who did it, so what? That’s it.” Instead, he launched straight into the literary world of hardcover fiction. He aspired to be, as he told Elizabeth Mehren in an August 12, 1980, Los Angeles Times profile, “an American Balzac.” Burnett revealed to Cecil Smith that his inspirations were the French Naturalists, not only Balzac but also Flaubert and Maupassant. When it came to American literature, he praised Mark Twain and singled out only four novels from his lifetime that he thought would stand the test of time: Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms and The Sun Also Rises, Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, and Appointment in Samarra by John O’Hara.

Fitzgerald’s influence is particularly noticeable in how often Burnett’s characters are obsessed with class (often lost class status) and their struggle to (re)climb the social ladder. Burnett’s characters also mimic his own literary tastes. In “Jail Breaker,” a 1934 Collier’s serial featuring a statistician whose first novel is about the gangster hiding out in his apartment, the writer spends his lunch hour reading Balzac and shares Turgenev books with the office secretary over whom he pines. And characters in both The Silver Eagle (1931) and King Cole (1936) quote the same Francis Bacon passage: “It is a strange desire, to seek power and to lose liberty: or to seek power over others and to lose power over a man’s self.” (Burnett quickly dispensed with such heavy-handed thematic pronouncements.)

Stylistically, Burnett’s prose derived from the idiomatic phrases and cadences of his characters and their worlds, a practice he began in Little Caesar and continued throughout his career. In a hyperbolic act of self-mythologization (and pure ballyhoo), Burnett exploited his own writerly origins for the plot of “Jail Breaker,” whose protagonist conceives a literary career based on the escaped killer holed up in his apartment:

In a flash, he saw how he could write his book and make it something beyond the commonplace story of a bandit, written for commonplace, illiterate readers. He would write it in the simplest language possible, using the idiom of the man himself; the average newspaper reader would find this to his taste, but would never suspect that he was reading an exercise in style and that the author was deliberately avoiding the use of literary English.

Such is the game that Burnett would play throughout his books, subverting expectations by eliminating whodunit plots, red herrings, and other typical elements of the conventional crime novel and focusing intently on the characters and their private worlds.

For the decade after Little Caesar, Burnett confined his crime writing to the screen and to magazines; his full-length novels were dedicated to more literary pursuits. Traversing the Midwestern social strata, from the gutter to the gentry, these books revealed Burnett as a sharp critic of the American class system. In Iron Man (1930), a pugilist fights his way up from the gutter, only to discover too late that he’s been a victim of exploitation all along. The Silver Eagle focuses on a business investor trying to stay clean in the underworld of Prohibition-era Chicago. The Giant Swing (1932), a Sherwood Anderson–esque melodrama, tells of a small-city pianist with dreams beyond the bandstand. Burnett’s own hotel experiences — and gambling addiction — inspired Dark Hazard (1933), about a night clerk with an eye for horse and dog racing. Among Burnett’s most formally experimental works is Goodbye to the Past: Scenes from the Life of William Meadows (1934), a proto–Citizen Kane that tells the life story (in reverse) of an Old West pioneer turned industrial mogul. Burnett mined his own political background for King Cole, in which a gubernatorial candidate incites riots and an assassination attempt in order to strike fear into farmers and win their vote. This is among the most impressive — and frighteningly still relevant — of Burnett’s early works. Closing out the decade was Dark Command (1938), a vicious frontier story about a Quantrill-esque character, subtitled “A Kansas Iliad.”

Even more so than in Little Caesar, Burnett’s non-gangster novels reveal the depth of his cynicism, and his preoccupation with the hypocrisy and venality of American society. “You show me an idealist and I’ll show you a goddamned fool,” declares newspaper editor Joe Hill in The Quick Brown Fox (1942). Whether they’re leeches sucking dry a mark as in Iron Man, drugstore waiters and dance-hall musicians as in The Giant Swing, or cogs in a political machine as in King Cole, Burnett’s characters are trapped in transactional relationships: everybody is using everybody else.

Think of Burnett as the flipside to an optimist like Horatio Alger, the iconic 19th-century American author who peddled parables of guttersnipes successfully pulling themselves up by their bootstraps to be, to quote the eponymous Ragged Dick, “’spectable.” While nearly a century separated the two authors, Burnett himself invites the comparison in The Quick Brown Fox, in which a young reporter gets ensnared in corrupt journalism and politics. After Ray Benedict’s father loses his newspaper during the Depression, Ray works himself up from cub reporter, in an effort to regain his family’s lost status; along the way, he turns ne’er-do-well Brant Harding from a disreputable expat into a congressional candidate with an article that falsely places him at Dunkirk. A radio announcer describes Harding’s meteoric rise as a “typical American Horatio Alger story.” But whereas Alger wrote about American dreams, W. R. Burnett traded in nightmares. Both authors were obsessed with protagonists driven to rise to the top. Unlike Alger, however, Burnett’s characters invariably fall. Fast — and hard. Such is the fate that awaits Brant Harding. And while Ray escapes with his life, he’s lost his innocence, his belief in heroism, and his trust in journalism, and he has fallen a few rungs back down the social ladder.

Despite not carrying tommy guns, Burnett’s non-gangster protagonists are often variations on Little Caesar’s Rico. Nightclub entrepreneur Frank Harworth may feign moral superiority by not selling bootleg liquor in The Silver Eagle, but he, like Rico, is motivated by all-consuming greed: “A man’s entitled to all he can get!” and “A great man, he told himself, is one who succeeds.” Like pawns out of Greek tragedy, Burnett’s characters are doomed from the start. “Most men blamed everything but themselves for their misfortunes,” reflects industrialist Bill Meadows in Goodbye to the Past. “It was too easy to curse your luck. Barring accidents, a man generally got what he deserved.” Nor is the irony of his protagonists’ hubris lost on themselves. “Funny!” remarks the boxer in Iron Man. “When I didn’t have Rose I figured if I could find her, I’d never be lonesome no more. Funny! Yeah, and when I was a kid I thought if I could ever be champion I’d be the happiest guy on earth. Funny, how things are!” The archetypal Burnett male is one who aspires to everything and winds up with nothing. Ultimately, they all suffer the same fate, which is summed up best by the title of Burnett’s 1943 novel Nobody Lives Forever.

Just over a decade after Little Caesar, Burnett returned to the crime novel proper with High Sierra, which transported the author’s own interest in the Old West (as evidenced by his 1930 retelling of Wyatt Earp, Saint Johnson) into modern times. The novel begins with one of the masterpieces of first lines in all of crime fiction, rivaling even James Crumley’s The Last Good Kiss (1978): “Early in the twentieth century, when Roy Earle was a happy boy on an Indiana farm, he had no idea that at thirty-seven he’d be a pardoned ex-convict driving alone through the Nevada-California desert toward an ambiguous destiny in the Far West.” This tells you everything you need to know about Earle and the fate that awaits him.

With Burnett, situation — not plot — is key. “I don’t have any plot in my books. Just life. And the relationship of characters and what happens to them,” he revealed to Mate and McGilligan. “[I]n the motion picture business, the plot takes the place of everything else. The plot’s all there is, and the characters are names.” The story of High Sierra is a reworking of Little Caesar. A group of men plan a robbery. The boss warns them not to kill anybody. Invariably, somebody is killed, and the law closes in on the gang. What makes High Sierra different from Little Caesar — and from Burnett’s earlier novels — is its cast, particularly its two strong female characters whose agency throws even hardened gunman Earle for a spin: “dime-a-dance” Marie Garson, along for the heist, and club-footed Velma, relocated from Ohio to Los Angeles with her grandparents. And whereas Burnett’s 1930s books could at times slip into soapy subplots, High Sierra is lean and propulsive, handling curves like an expert driver making a fast getaway.

Perhaps taking a cue from High Sierra’s success (the book and its film adaptation were big hits), Burnett didn’t wait a decade before writing another crime novel. Nobody Lives Forever appeared in 1943, in part inspired by a minor character in High Sierra, a disbarred doctor slumming it in California. In this novel, junkie Doc Ganson, hearing about a wealthy widow worth a million bucks, sets in motion a long con that will allow suave chisler Jim Farrar to take her for $100,000. Problems arise when Jim tries to buy out Doc and his gang cheap, while marrying the widow and keeping her fortune for himself. Doc doesn’t play along, and the book’s title should be some indication of how things work out — or don’t. Doom-laden with premonitions of war, Nobody Lives Forever is one of Burnett’s darkest portrayals of American society. The novel quickly found its way to the big screen, adapted by Burnett and starring John Garfield.

Burnett gave his cynicism a rest in his next novel, Tomorrow’s Another Day (1946), in which cocksure gambler Lonnie Drew wins a legitimate restaurant, steals department-store model Mary Donnell away from her gangster boyfriend Jack “The Greek” Pool, and then foils Pool’s plan for revenge. Prosperity, good fortune, and a happy ending seem entirely out of place in Burnett’s world — leaving me to wonder if perhaps the author was having a lucky streak at the track when he wrote this one. Next up was even more uncharacteristic, a clumsy attempt at a Rebecca-inspired gothic melodrama, Romelle (1946), in which a recently fired lounge singer is unnerved by her husband’s late-night wanderings, the locked storeroom in his Colonial-style mansion in the San Fernando Valley, and the stalker from his mysterious past.

Closing out the 1940s, Burnett again returned to the Little Caesar template for his third great crime novel — and arguably most influential work — The Asphalt Jungle (1949). Once more, he tells the story of a group of professional criminals who plan a robbery that goes bad, and their inevitable demise. Recently paroled criminal Erwin Riemenschneider wants to hit a jewelry store for half a million bucks in gems, but he needs attorney Alonzo Emmerich to finance the deal and gunman Dix to play “the hooligan” in case anything goes wrong. What Riemenschneider doesn’t know is that Emmerich is broke and is planning to double-cross the team.

Eschewing the single-protagonist focus that characterized most of his earlier work, Burnett adopted a multicharacter perspective that set the standard for ensemble crime narratives for decades to come. Its imprint can be seen everywhere, from Lionel White’s Clean Break (1955; filmed in 1956 as The Killing) to Donald Westlake’s comedic caper The Hot Rock (1970) to more recent fare such as S. A. Cosby’s Blacktop Wasteland (2020) and the Fast & Furious movie franchise. What makes The Asphalt Jungle so brilliant isn’t mystery (there’s none) or suspense (even the characters seem prepared for the jewel heist to go off the rails), but the constantly shifting psychological power plays between characters, who are always withholding information from one another or working an angle.

The 1950s began with Burnett returning to the Western with Stretch Dawson (1950), about a gang of outlaws who get trapped in a ghost town by an elderly miner and his gun-wielding granddaughter. Originally sold directly to Hollywood two years earlier (and filmed as Yellow Sky), Stretch Dawson was, in many ways, a portent of things to come for Burnett. Seven more Westerns would follow over the next 13 years. It was also his first novel not to appear in hardcover. Paperback originals marked a permanent change in the publishing industry, and like the antiheroes of his novels, Burnett had to fight to keep his place.

Little Men, Big World (1951) — which could aptly describe almost any of Burnett’s novels — and Vanity Row (1952) completed what the author described to Mate and McGilligan as a trilogy that began with Asphalt Jungle, “a study of corruption of a whole city in three stages: status quo, imbalance, and anarchy.” Little Men, Big World is another ensemble crime narrative focusing on Arky, a bookie whose world is collapsing fast: a rival gang across the river is threatening to move in, journalist Ben Reisman is working to expose the city’s underworld, and Police Commissioner Stark wants to run the criminal element out of town. In Vanity Row, corrupt cop Roy Hargis is under pressure by both lawful and unlawful forces to pin the murder of a lawyer on the deceased’s mistress — for whom, naturally, Hargis falls.

Burnett continued to produce novels throughout the 1950s and ’60s, though they were increasingly released as paperback originals. Two late books that bore his name were not even finished by Burnett but by a then up-and-coming novelist named Robert Silverberg. “I was handed a vast mass of almost incoherent manuscript by my agent (his agent too) and asked to carve a novel out of it,” Silverberg recalled. “The result was The Winning of Mickey Free (1965), which Bantam published.” Silverberg also completed Round the Clock at Volari’s (1961), released under Fawcett’s Gold Medal imprint. “I wasn’t ghosting the books,” Silverberg clarified, “just putting the disorderly manuscripts into publishable form.”

Among Burnett’s most unusual and experimental late work is It’s Always Four O’Clock (1956), a Hollywood jazz novel originally appearing under the pseudonym “James Updyke.” Guitarist Stan and bassist Walt are roommates, picking up gigs and girls when they can. One night they encounter Royal, a manic-depressive pianist with a drug habit and a musical sensibility far beyond what either man has encountered before. Forming a group, the three cause a stir in the local scene, inspiring imitators and drawing leeches that want to commoditize them. Formally, Burnett takes his interest in vernacular to its furthest extreme, employing a conversational first-person style, as though Stan is gabbing directly to the reader between cigarettes. Thematically, it reaches back to his earlier music novel The Giant Swing, but with greater maturity and even deeper cynicism.

One of the author’s rare books about artists, It’s Always Four O’Clock taps into a deeply personal issue for Burnett: how to retain artistic integrity in a commercial system built on exploitation. Walt is the ambitious one, willing to sacrifice himself for a paycheck. At the other extreme is Royal, whose artistic aspirations result in self-destruction. And on the outside is Stan, one of the few Burnett protagonists to describe himself as a “bum,” who aspires to nothing higher than a few drinks and a few laughs with a girl. By the end of the novel, Stan is right back where he started. Perhaps it’s a sign of Burnett’s own hard-earned wisdom that he finds something admirable in such mediocrity. Two decades earlier, the composer of The Giant Swing would never have settled for such comfort.

Despite his contempt for the form, Burnett also continued working on screenplays, including Captain Lightfoot (1955), an adventure tale of 19th-century Irish rebels based on the author’s 1954 book of the same title; September Storm (1960), a 3-D extravaganza about fashion models and lost treasure off the coast of Majorca, based on a story by Steve Fisher; Sergeants 3 (1962), a Rat Pack version of Gunga Din with Burnett also providing a novelization; and perhaps his most famous film of all, the POW classic The Great Escape (1963), co-written with James Clavell. “I could never take movie writing seriously enough,” he told Elizabeth Mehren. “It’s communal writing, it’s got to be. What kind of writing is that?”

After passing the 1970s without seeing a novel published, Burnett enjoyed a late career renaissance. In 1980, the Mystery Writers of America awarded him their highest honor, the Grand Master Award. And in 1981, Burnett published what would be his final novel. Fittingly titled Good-Bye, Chicago: 1928; End of an Era, it not only marked a return to the gangster genre with which he began his career but was also a farewell to the city that launched him. Set in the same time period as Little Caesar, the novel begins with the discovery of a woman’s body floating in the Chicago River. She is later identified as Sergeant Joe Ricordi’s ex-wife Maria, who disappeared from her husband’s life several years ago without a trace. Characteristic of Burnett, he is not interested in the mystery, right away telling the reader that her death was due to an overdose of narcotics, and identifying who dumped the body. Instead, as in The Asphalt Jungle, Burnett focuses on networks and hierarchies among the characters, and the interconnectedness between crime, law, politics, and journalism. Cops rub shoulders with crooks, politicians dine with gangsters, and everybody is touched in some way by a never-ending cycle of corruption.

Good-Bye Chicago also harkens back to a theme that was central to almost all of Burnett’s work starting with Little Caesar: ambition as an insatiable, all-consuming, all-American urge. Ted Beck is a mid-level syndicate pimp who ordered Maria’s body to be tossed in the river. Worried that its discovery will lead to his downfall within the organization, he muses on all that he has gained, and all that he has to lose: “Ted poured himself a drink and stood in the middle of the big living room, looking about him at the elegance. He’d come a long way from the Stockyards, a very long way. His secret fear was that suddenly he’d be deprived of all he’d won.”

Ted is no different from any of Burnett’s earlier protagonists. The pianist in The Giant Swing would never be satisfied with a mere bandstand. The industrialist in Goodbye to the Past cannot relinquish control of his company while he is still alive, even though he is past the point of running it himself. The gambler in Dark Hazard, even after losing everything, gives up what little he has left to return to the track with his dog. And Dix, in The Asphalt Jungle, still refuses to let the jewels go, even after the heist has gone belly-up. Ted Beck knows better, but still he clings to his ambition, even if it means his demise. As the titular character in Burnett’s 1936 serial “Dr. Socrates” reflects, “A man very seldom chooses his fate; it chooses him.” Burnett’s characters may dream of greatness, but in the end, all they’re destined for is a great fall.

¤

LARB Staff Recommendations

An Obscure Road to Hollywood

A republication of Philippe Garnier’s 1996 book on screenwriters in 1930s Hollywood.

Tired of Living, Afraid of Dying: Horace McCoy’s Legacy

Horace McCoy’s depression lasted longer than the country’s.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!