Performing the Patient: On Emily Wells’s “A Matter of Appearance”

Emma Cohen reviews Emily Wells’s memoir of chronic illness, “A Matter of Appearance.”

By Emma R. CohenJune 20, 2023

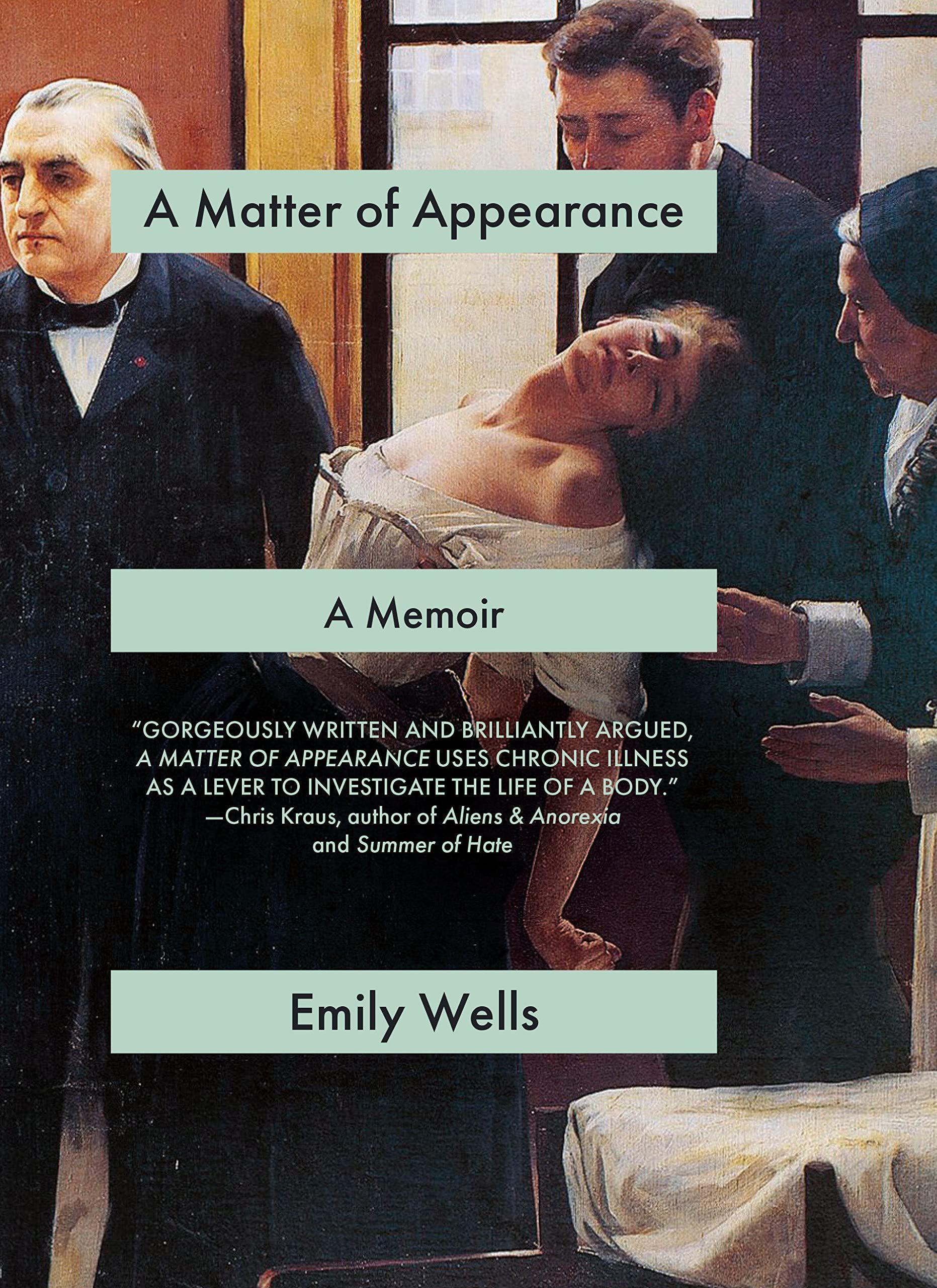

A Matter of Appearance by Emily Wells. Seven Stories Press. 192 pages.

IN THE HUMAN CONDITION (1958), Hannah Arendt writes that “the most intense feeling we know of, intense to the point of blotting out all other experiences, namely, the experience of great bodily pain, is at the same time the most private and least communicable of all.” I’m wary of these near-truisms about the incompatibility of language and pain—at this point, there are too many excellent poems and novels and memoirs that deal with the challenging textures of embodiment (think of the work of Alice Hattrick, Kim Hyesoon, or Amy Berkowitz) to believe that the experience of pain is confined to the bounds of individual subjectivity. Still, it’s fair to say that talking about the exhausting, messy experience of the body, wresting it out of the private and assigning to it a shared vocabulary without losing the distinctive quality of physical sensation, is a difficult task.

This task is deftly managed by Emily Wells in her new memoir A Matter of Appearance, where she manages to shift the issue of pain into the public sphere without pretending that it is easily legible. Instead of asking simply whether pain can be articulated, Wells asks how the difficulty of this articulation, or the assumption that it is impossible, has contributed to the skepticism that suffuses the diagnosis of contested illness, and the persistent marking of feminized pain as psychosomatic and hysterical. Probing her own experience living with a chronic illness that long went undiagnosed, Wells is simultaneously entranced by Augustine Gleizes, a patient of 19th-century neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, who extensively photographed and publicly exhibited images of Gleizes’s symptoms of hysteria throughout her treatment. Wells engages herself not only with negotiating “a way to interpret bodily semiology when physicians could not,” but also with finding new methods to “convey the perpetual newness of chronic pain.”

Alongside an attention to the cultural history of pain, as well as the present challenges of managing illness amidst the structural failings of capitalism, Wells also turns to her childhood ballet training as a site of investigation. Fervently attached to the “cruel ferocity” of ballet, and to the narrative it offers that “the most beautiful, meaningful pursuits would require correlating sacrifice,” the ballet studio became an arena in which Wells encountered and attempted to control the early flares of chronic pain. Steeped in a classical technique that demands mastering the body to transcend its quotidian limitations, Wells writes that “though this nameless pain continued interrupting my life, I was still able to insist upon a kind of belligerent sovereignty over my body, which had already been offered up to ballet, had already been spoken for.”

Like Wells, my young life was tightly wound with the rigors of ballet. And, just like for Wells, the unpredictability of illness threatened to disassemble the carefully molded technical system that granted me control over my limbs. When, dressed in a thin-strapped leotard, I looked in the mirror and noticed the bulge of a malignant tumor, I was annoyed by the disruption of the gentle curve from my neck to my arm raised in fourth position—I thought perhaps I was unwittingly lifting my shoulder too high, deviating from the alignment necessary for a smooth attitude turn. After my diagnosis, as I went through treatment, I continued to dance, to the bewilderment of some of my teachers. On a superficial level, sickness can seem incompatible with ballet, an art form often so incapable of accommodating deviations from its strict norms. What does a mess of bodily fluids and chemicals, swollen limbs and frayed nerves, have to do with the ethereal movements of bodies on a stage?

Yet, as Wells observes, there is also a strange affinity between ballet and illness. Looking at The Natural History of the Ballet-Girl by Albert Smith, a tongue-in-cheek “Social Zoology” of ballet published in 1847, Wells notes that ballet dancers, although routinely idealized, could also be understood as sickly and pathological, weakened by their labors and rendered hysterical through their constant occupation of intense, shifting emotion on stage. And then there’s the added fact that the self-disciplining practice of ballet prepares us so very well for performing the role of the “good patient,” which requires meticulous self-surveillance and restraint. As Wells writes, “[D]ancers, I thought, were ideal patients: compliant, receptive to critique, and pleased to solve problems through bodily manipulation.”

Sociologist Stefan Hirschauer has written about the sculptural quality of medicine in the way that surgeons sift through muscle and bone in order to produce a body that more closely adheres to the two-dimensional images of an anatomy textbook. Ballet, too, aims to sculpt flesh, drawing an idealized form out of the body’s raw material. Both the medical gaze and the self-evaluating gaze of the ballet dancer involve rooting out imperfection and charting out paths towards imagined models.

There are times, too, when the gaze of the camera begins to appear like its cousin the X-ray, the photograph becoming a process of diagnostic capture. It is this dynamic that emerges in the images of Augustine Gleizes that pepper Wells’s book. Framed by Dr. Charcot, that “Napoleon of neuroses,” Gleizes twists into poses that are then cataloged as various “passionate attitudes,” markers of her hysteric fit. On the one hand, Wells suggests that, in their physical excess, “it is impossible to decipher Augustine’s photos from [a] clinical distance,” and on the other hand, “she is all symptom.” Regardless of her internal state, Augustine’s limbs, in the composition of these photographs, are arranged to produce the postures of the hysteric.

We perform for the camera, we perform for the doctor, we perform for the audience. Wells reveals the way that these different modes of bodily presence, though distinct, might also be intertwined. I wonder too if, alongside these medical and artistic performances, we also perform for the page. What happens to the medical gaze when it merges with the backwards glance of the memoirist? Unlike many authors, who work to construct a stable “I” out of the scattered bits of their past experiences, Wells acknowledges that her “sense of a coherent self has been marred.” If ballet and medicine produce disciplined subjects, perhaps the act of writing a memoir that acknowledges discontinuity can operate as a countervailing force, dispersing the self rather than stabilizing it.

Of course, attending to discontinuity is often necessary for material that engages with the experience of illness. For a school project, my friend asked me about my experience during cancer treatment, and I tried to explain that I could feel my body breaking down around me, that I was in comfortable denial about my mortality, and at the same time I thought, “This must be what it feels like for a body to die.” I bristled when I saw her writing down “Cartesianism”—I didn’t believe in a mind-body dualism. Intellectually, I understood myself to be a complex body-mind at best, or, more realistically, a fragmented assemblage of sensations, thoughts, and habitual emotions. I understood this, and I also found it difficult to describe my experience in terms other than those I had initially chosen: that I was inhabiting a body that was familiar and alienated and in flux. As Wells writes, “[D]ualism plagues everything.” For me, as for Wells, “the self that observes its own illness for a prolonged period of time is vulnerable to that mind-body split,” whether or not it’s right, whether or not it believes what it’s experiencing. I catalog Wells’s words next to those of Anne Boyer from her 2018 book A Handbook of Disappointed Fate. “Disease has bullied me into Cartesianism,” she writes, “but the mixed tears undo division through liquification.”

Years after the tumor, I tried to make some sense of my experience, which had stayed with me on a visceral level, even if I rarely spoke of it. There are a few cryptic lines sitting in my Notes app from this period, moments when I stumbled across an articulation that rang true. “There are parts of me apart from myself,” reads one. After a lecture at Triple Canopy, I trawled the New York Public Library for a copy of Lana Lin’s book Freud’s Jaw and Other Lost Objects: Fractured Subjectivity in the Face of Cancer (2017). I felt a soft tingling as I came across a quote that she includes from Jean-Luc Nancy, who had just gone through a heart transplant that preceded his cancer diagnosis: “A gentle sliding separated me from myself,” he writes. Reading it again now, I can see that the line isn’t the same as the one in my note. His operation produces a different tenor than my dissociation. Still, when I first came across Nancy’s words, I felt thrilled to have discovered a piece of writing that resonated with a sensation I assumed was beyond language. I wasn’t seeking someone who had had the same experience as me. But I was seeking proof that some of the more uneasy qualities of what I had experienced weren’t entirely isolated—that they might pull me into a written network of illness, of strange embodiment.

This loose network of literary affinity surfaces throughout Wells’s memoir and is baked into its structure. Hers is not the illness narrative that traces a narrator’s progression from symptom to diagnosis to treatment. It doesn’t operate as a guidebook for those faced with the same fortune. Instead, a range of voices are allowed to mingle with her “I,” and cultural criticism molds and amplifies personal recollection. Amidst Wells’s account of her own pain is an engagement with Hervé Guibert’s To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life (1990) and Susan Sontag’s Alice in Bed (1991), and frames of personal experience are spliced with images from the film Safe (1995) and the 1841 ballet Giselle.

Undergirding these moments of analysis is another form of connection, the continual return to the life of Augustine Gleizes. Reflecting on her preoccupation with Gleizes, Wells writes:

Perhaps women like myself, promiscuous pattern-seekers, go looking for ourselves in Augustine, that we might find in her a model for how we too can turn the landscape of mind and body into a black-and-white object from which we are detached, free to be posed and prodded without bother.

In this view, Gleizes is a model for self-objectification, a tool for getting beyond oneself by looking outward. But Wells continues, “Maybe we seek to connect our present with the past of another person, as if by venerating her, we grant dignity to our own suffering.” When the afflicted is no longer seeking a state of mutual dissociation, objectification here becomes a way to legitimate pain, whether by turning oneself into a work of art or by merely recognizing that the concern one holds for a figure in the past might be extended to oneself in turn. Regardless of the precise motivation or effect, Wells points to a connection between herself and Gleizes that reaches across an expanse of physical experience and history: “Augustine continues to come to me; I continue to transcribe her; we are united in having been rendered in a language that cannot account for us.”

This sense of haunting, finding moments of fellow feeling through illness, even when your experiences only momentarily correspond, is familiar to me. Reading A Matter of Appearance, I found myself underlining hungrily, littering the margins with exclamation points of recognition and copying lines into my notebook, where Wells’s words now keep company with those of David Wojnarowicz and Audre Lorde, Emma Bolden and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. I like to think that this process of fragmentation and collection is invited by the text itself: A Matter of Appearance continually spurs itself towards the collective. “My fundamental task is not to claim the tragic for myself,” Wells writes, “but to acknowledge those who make up the world of the sick; to create a space out of words for us to convalesce in together.” I can’t think of a better literary project than carving out a room for shared convalescence. At the same time, I find myself wondering whether this project might offer more than rest, whether convalescing together could lead us to modify, or even do away with, the conditions that produce this unevenly shared fatigue.

¤

LARB Contributor

Emma R. Cohen is a dance artist and freelance writer currently based in Chicago. She is pursuing a PhD in literature at Northwestern University.

LARB Staff Recommendations

On Excavating the Novel and “Toni Morrison: Sites of Memory”

Jasmine Liu visits Princeton University Library’s exhibition of Toni Morrison’s archive.

Sometimes I Am What I Really Am: On Mark Alice Durant’s “Maya Deren”

Emma Kemp reviews Mark Alice Durant’s new biography of the enigmatic experimental filmmaker: “Maya Deren: Choreographed for Camera.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!