On Excavating the Novel and “Toni Morrison: Sites of Memory”

Jasmine Liu visits Princeton University Library’s exhibition of Toni Morrison’s archive.

By Jasmine LiuMay 6, 2023

HOWEVER UNLIKELY a place to begin one’s critical investigations, I have always read the forewords of novels eagerly, with a hope that the writer will let slip crucial details about their sources of inspiration and creative process. Recently, in preparing to visit an exhibition of Toni Morrison’s process papers, “Toni Morrison: Sites of Memory,” on view at Princeton University Library, I became fascinated with Morrison’s forewords to her novels—succinct yet highly technical exegeses of her creative muses, opening sentences, archival practices, and historical and psychological preoccupations.

My specific attraction to her forewords, I suspect, emanates from the contrast they draw with her novels, which construct imaginative universes so whole and total in their details, signs, and inhabitants that I frequently find them overwhelming. For me, navigating Morrison’s fictional worlds—awash with smells, colors, textures, flowers, and foliage—is much like traveling to a new city or country where my own feeling of foreignness is palpable. Her forewords offer to demystify the creation of these worlds.

“I always start out with an idea, even a boring idea, that becomes a question I don’t have any answers to,” Toni Morrison told The Paris Review in 1993. In her forewords, she lets readers in on what these questions are. The Bluest Eye (1970), her debut novel, was precipitated by a question that came to haunt her while she worked her day job as an editor at Random House: what were the “tragic and disabling consequences of accepting rejection as legitimate, as self-evident?” The answer took shape in Pecola, one of the most miserable, abject young girls to exist in English-language literature; the book would launch Morrison’s multi-decade career as the United States’ preeminent novelist and writer. Her second novel, Sula (1973), grew out of her interest in “outlaw women,” an interest that would persist through decades. What, she wondered, were the consequences of “a woman’s escape from male rule […] on not only a conventional black society, but on female friendship”?

Oftentimes her questions were sparked by flares from the historical archive that left afterimages that just wouldn’t let her go. The protagonist of Beloved (1987) was inspired by Margaret Garner—a historical figure Morrison encountered in her research for The Black Book (1974), a collection on Black life in America through the centuries. In interviews, Garner, who killed her own daughter to forestall a life of enslavement, calmly asserted that she would do it again if she had to. “That was more than enough to fire my imagination,” Morrison said. Later, she was captivated by a photograph by the famous documentarian James Van Der Zee. The image was of a 1920s funeral, and staged dramatically at its center was the open casket of a young woman who had been shot by her lover. What had led to this end? She needed to know. The image became the seed for her 1992 novel Jazz.

Work on The Black Book would be an inexhaustible source of creativity for Morrison. As she pored over “colored newspapers” and photographs from the period after emancipation, she discovered repeated exhortations for formerly enslaved people to move to utopian Black towns. She couldn’t help noticing, however, that the governors of these towns all seemed to be light-skinned. This made her question what it would mean to be freed from slavery only to again be confronted with colorism in a place marketed as a racial haven. What were the features that people sought from paradise anyway? That became the subject of Paradise (1998).

Like a scholar who enters an archive, Morrison embarked on each of her novels in search of an answer, only to emerge with more and more questions. Morrison’s forewords act as research abstracts, aligning readers with her inciting questions, and positioning them toward paths of further scrutiny. Professionally, she conceived of herself chiefly as an editor for much of her career and felt that she could see better than most how writers worked—their “process, how [their] mind worked, what was effortless, what took time, where the ‘solution’ to a problem came from.” She writes in her 1995 essay “The Site of Memory” that, for her, the resulting book was “the least important aspect of the work.” Revisiting her forewords and scrutinizing her archive, I am very much inclined to agree.

¤

“Toni Morrison: Sites of Memory” is loosely grouped into six categories. There are relics from Morrison’s schooling, when she served as an editor at her high school newspaper and participated in dramatic productions; early correspondence with editors who offered different advice on how she should proceed with her work; copious outlines, notes, and drafts for Beloved, Song of Solomon (1977), Jazz, and Paradise; and letters from such figures as Toni Cade Bambara and Nina Simone.

A first edition of The Bluest Eye included in the library’s exhibition succinctly demonstrates how her creative process mirrors the formal qualities of her finished work. Morrison’s trade paperback editions today have a uniform look—two-tone Vintage imprint covers with elegant, calligraphic title fonts. The unfussiness of The Bluest Eye’s first edition cover, designed by Morrison herself, is a tonic; printed plainly in standard Times New Roman font are the novel’s three opening paragraphs, which efficiently lay out the kernel of its narrative scandal.

The effect of the design has much to do with the power of the novel’s first lines. Pecola, who we learn wishes for nothing more desperately than blue eyes, is pregnant with her father’s child. The matter-of-fact way in which we are presented this disturbing detail suggests that we too are residents of Lorain, Ohio, so we must already know the story. For Morrison, immediately imparting this knowledge of rape and incest liberates her to pursue the narrative aims she really cares about. By revealing the entire plot at the outset, she said in an interview, she would know that anyone who kept reading did so for one of two reasons—to find out how it happened, or for love of the language. In other words, as she writes in the novel’s first lines, “There is really nothing more to say—except why. But since why is difficult to handle, one must take refuge in how.”

¤

Morrison was a ravenous researcher. Her hunger for archival materials was the product of a foundational lack—the absence of interiority in narratives chronicling Black American life. In “The Site of Memory,” Morrison wrote of the development of the African American literary canon from slave narratives to abolition tracts to contemporary fiction. She argued that Black writers had been stuck writing for white audiences; historically, their principal concern was with representing themselves in a sympathetic manner that would be productive for the cause of emancipation and later the securing of civil rights. But this meant omitting ugly and unpalatable truths. “Over and over, the writers pull the narrative up short with a phrase such as, ‘But let us drop a veil over these proceedings too terrible to relate,’” she wrote, attributing such rhetorical maneuvers to writers as diverse as Olaudah Equiano and Frederick Douglass. Because writing by Black people up until Morrison’s time had served as an exercise in packaging the Black experience for a white gaze, rarely did Black writers train their gaze inward, at least not for publication. “For me—a writer in the last quarter of the twentieth century, not much more than a hundred years after Emancipation, a writer who is black and a woman—the exercise is very different,” she wrote.

This new historical position that Morrison occupied demanded new techniques. For her, this took form in a process she called “literary archaeology.” “On the basis of some information and a little bit of guesswork you journey to a site to see what remains were left behind and to reconstruct the world that these remains imply,” she explained.

While writing Jazz, Morrison read every single Black newspaper published in the year 1926, and fragments of her research and source materials for the novel are on view at Princeton’s Firestone Library. Set in New York in the 1920s, Jazz—much like the African American musical form that so entranced Morrison—is improvisational, polyvocal, and atmospheric. Between the thriving publishing culture and the rich photography of the Harlem Renaissance, Morrison would have had an abundant historical archive to work with. In one message fired off to an assistant at the time, she included research requests for “some photographs of streets in fairly nice residential neighborhoods in mid-nineteenth century”; “a 1925 and 1926 discography of blues recorded during those years”; and “more, and as much more as possible, on the East St. Louis riots and the response among Black people.” She also inquired about when Coney Island was established as a resort, whether it was segregated, and what Jim Crow laws were like on trains in the 1920s. Morrison was seduced by the romance of the Jazz Age and the backlash that ensued—the liberation, sexual and otherwise, that also engendered moral puritanism and chauvinist violence. This was a dynamic that she returned to repeatedly in books like Sula and Paradise.

Also collected in the exhibition is a typewritten set of notes titled “Jazzthoughts” in which Morrison puzzled through what she called the “bookvoice” of Jazz. Jazz, with its meandering, shape-shifting narration that features the voices of several female main characters as well as an anonymous narrator who occasionally addresses the reader in the second person, is often considered Morrison’s most experimental work. By the end, the narrator undermines their own authority, admitting that their conclusions are unreliable, their motivations biased and suspect.

Reading Morrison’s process notes on the bookvoice she hoped to achieve, I wondered if it sufficed as a description of her own positionality vis-à-vis the archive. “This bookvoice is shaken by its stumbling understanding of the personal histories of the characters—but resists any visceral or intellectual understanind [sic],” she writes. Only later in Jazz, “the bookvoice recognizes its errors of perception, the fact that it had a taste for pain, that it missed the people altogether and thereby missed the real possibilities of human love and reconciliation.” At the conclusion of hours and hours of research into obscure Black lives, speculating on their insecurities, their drives, and all those things that make up our interiority, she turned her own gaze inward.

¤

I have no memory for details about places I’ve been. Perhaps because of this, almost all of the paragraphs upon paragraphs of Morrison’s prose that I have transcribed by hand are descriptions of interiors, skies, plants, and trees. Even without the evidence of Morrison’s papers, her meticulousness in thinking about physical space is obvious. Her notes, which include blueprints, maps, and diagrams relating physical locations to emotions, confirm that visualizing and exercising spatial precision was an important part of how she probed the psychology of her characters.

Sometimes her spaces were characters. The haunted house, 124, wherein reside Sethe and Denver, Beloved’s isolated and ostracized mother and daughter, is “spiteful,” an entity with which they must wage “a perfunctory battle.” Its sideboards “step forward,” slop jars arbitrarily overturn, “gusts of sour air” blow. Sethe accepts her lot to coexist with 124’s venomous and retributive unruliness, an attitude that illuminates the way she conceives of herself in relation to their neighbors and their fate. On one piece of paper displayed in the “Thereness-ness” section of “Sites of Memory,” Morrison scrawled the layout of the ground floor of 124. Next to it, she analogized the inside and outside of 124 to two principal characters: the former with Sethe, who she associated in her notes with a “retreat into fantasy/invention” and a rejection of “what rejects her,” and the latter with Stamp, a character she associated with “community obligations to the weakest link,” “news of the world,” and “moral war.”

But the most intricate physical space that Morrison developed was Convent, in Paradise. A former Catholic abbey turned female co-op, Convent is a mansion that functions as the nerve center for a ragtag intergenerational set of women who have rejected romantic and familial attachments in favor of living together, “seventeen miles from a town which has ninety miles between it and any other.” Once again, Morrison plops the most shocking plot point down on the novel’s first page: a group of men from the nearby town of Ruby have come to Convent on a murderous rampage, ready to commit a spectacular act of violence. But reading Paradise’s opening scene, it is possible to forget that these men are there to kill. As they progress through the many open spaces and hallways of the mansion, the narrator lapses into an objective, meditative cadence.

The ornate and newly co-opted mansion once belonged to an embezzler, and the narrator carefully enumerates all these luxuries, including “bisque and rose-tone marble floors [that] segue into teak ones,” “princely tubs and sinks,” “macramé baskets,” “Flemish candelabra,” a bathtub that “rests on the backs of four mermaids.” Also ingrained in the mansion’s history is the fact that it served for a time as a boarding school for Arapaho children who were forced, under the instruction of Catholic nuns, to undergo an “education” of cultural erasure. We learn that the nuns have dutifully removed the marble carvings of nymphs throughout Convent, but remnants of nymphean hair still remain. Although the figure of the embezzler stays out of view, largely irrelevant to the concerns of the novel, we become intimately familiar with his biography, and his paranoia, because we spend so much time in the very particular architecture of his home. The building’s layered pasts rise to the novel’s surface, as various built-in memories prompt the men of Paradise to reflect on how they wound up in Ruby, and how times have changed.

Morrison’s pencil-and-paper sketches are a record of how she translated the embezzler’s neurosis into materiality and how she arrived at the mansion’s fantastical psychological design, which was constructed for “voluptuous part[ies]” and shaped after “a live cartridge,” with its interior sunlight “always misleading.” In Paradise, references to the architecture of Convent serve the double function of calling readers back to the story-within-a-story of the embezzler, one that has the compact power of microfiction. In her drawings, Morrison notes the function of each room, marking the locations of doors, stairs, and passageways that residents and intruders would pass through. Convent—by maximizing the potentials of symbolism, irony, and the affective impact of different qualities of space (light, shape, material)—theatrically stages the dramatic power of constructing a place through excavating its many histories.

From the peculiar and portentous bullet-shaped mansion, we surmise that shapes were meaningful to Morrison. She wrote like a synesthete, and much like her relationship to color, she had an oracular intuition for shapes too. On a sheet of notes, she ascribed basic geometric shapes to each of the nine women whose stories make up Paradise—Ruby as a square, Mavis and Consolata as circles, Seneca and Divine as circles inside of squares, and so on.

At the library, I scrunched my eyes to decipher the marginalia hastily scribbled alongside her sketches of shapes. Later, on the train home, I took out my copy of Paradise, which I had brought along with me, her enigmatic shapes front of mind. I tried to develop an analysis for why each character had been given their shape, but eventually gave up. I realized that this is where Morrison’s archive could only offer more questions, not answers. Her shapes are flares from the writer’s mind that won’t let me go for a while, and I am glad for them.

¤

Jasmine Liu is a writer from the San Francisco Bay Area currently based in New York.

¤

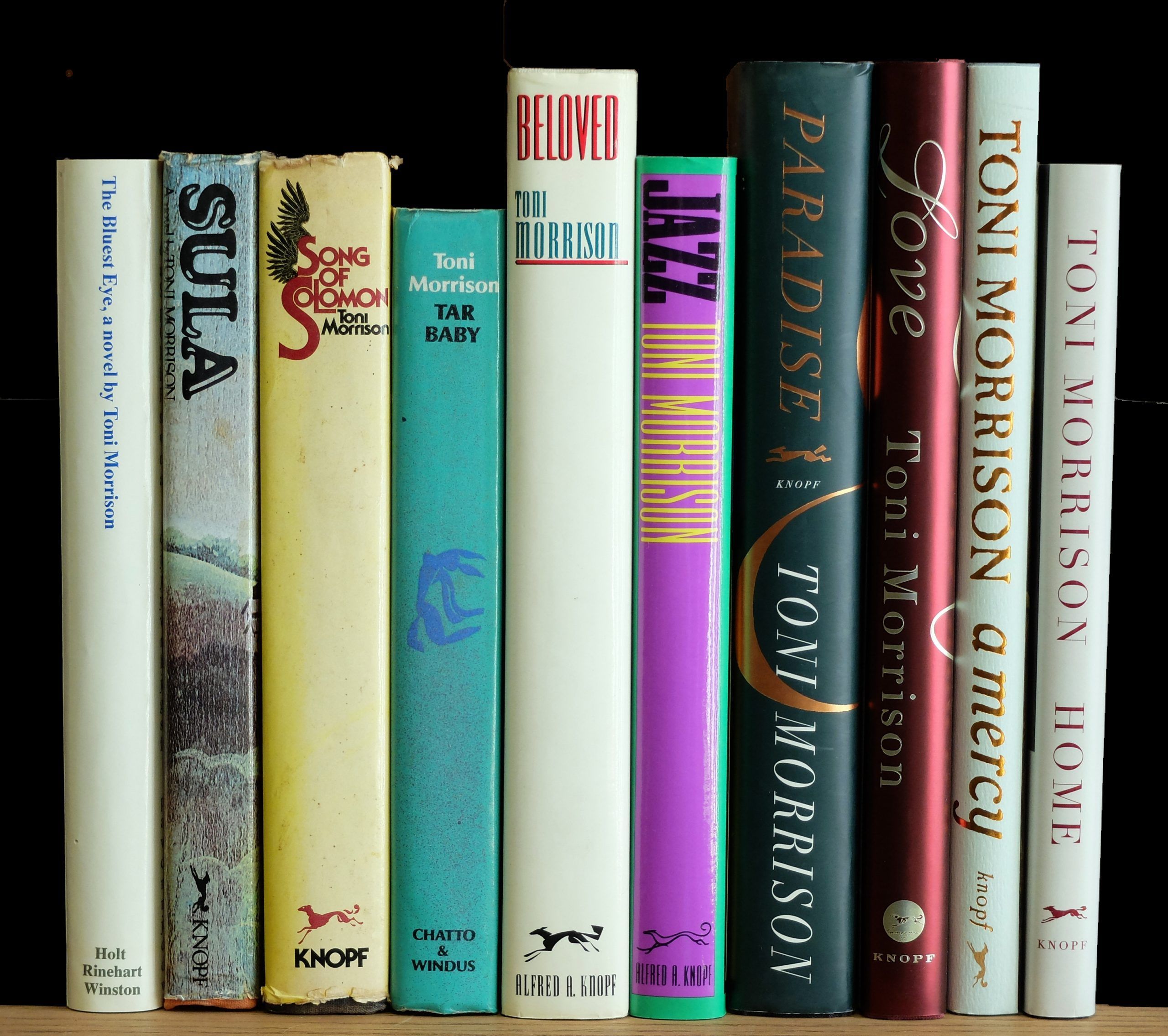

Featured image: Toni Morrison novels, first editions. Special Collections, Princeton University Library. Photographer: Brandon Johnson, Princeton University Library.

LARB Contributor

Jasmine Liu is a writer from the Bay Area based in New York.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Fictional Blues: Narrative Self-Invention from Bessie Smith to Jack White

An illuminating, thought-provoking, refreshingly broad-minded new book about the blues.

Moments and Memories with Toni Morrison

Allison Adelle Hedge Coke, Quincy Troupe, Margaret Porter Troupe, and Ishmael Reed offer their memories of Toni Morrison.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!