Penelope Fitzgerald Was Here: An Appreciation

"Penelope Fitzgerald’s story was both permission and company; it was okay if I too had to start late and move slowly as a writer."

By Courtney CookJanuary 23, 2015

THE SETTING: A suburb of Sydney, Australia, February 2000. In a red-roofed bungalow shaded by giant eucalypts, I read a New Yorker profile by Joan Acocella about a writer I had never heard of, and it changed my life.

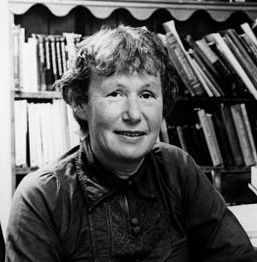

The essay, “Assassination on a Small Scale,” was about Penelope Fitzgerald, a British writer who published her first book as she neared the age of 60, and who went on to write several books of well-regarded nonfiction and nine, slim, perfect novels. She won the Booker Prize for Offshore (1979), and three of her novels were subsequently shortlisted: The Bookshop (1978), The Beginning of Spring (1988), and The Gate of Angels (1990). In 1995 she won the National Book Critics Circle Award with her last novel, The Blue Flower — a book pretty much universally acknowledged as a masterpiece. The facts of Fitzgerald’s writing career floored me. I didn’t even know starting that late was allowed when it came to book-writing.

I was just 30 years old when I read this article, and I couldn’t even afford The New Yorker in which it was published. Between the exchange rate and the airmail mark-up on American serials at the local news agent, the magazine cost about twenty US dollars. Still, it shouldn’t have been out of my reach. My husband and I were American expats with Ivy League degrees, the dot-com boom was still on, and we were supposed to be swaggering around Sydney waving American dollars, eating at Rockpool and Bills, weekending in South Australian wineries, and living in Bondi like all the other American expats who were working for big international companies. My husband was supposed to be on partner track. I was supposed to be working on my second novel like the other students in my MFA program, most of whom were younger than I was.

Except that global capitalism was letting us down. My husband’s big-name consulting job paid in AUD, but his big-name business-school loans were in USD, and by 1999 the exchange rate was against us. The price of the MBA had inflated at the same rate as an American magazine the moment we stepped off the plane and squinted into the bright, odd, north-facing Australian sunlight. We had somehow managed to buy high and get paid low during the biggest boom of our generation. I had two school-age kids to take care of — a privilege that was not only financially draining in the ordinary ways, but time-expensive. I was broody on the subjects of motherhood, creativity, and self-actualization, feeling like I was in some way fated to be on the wrong side of things.

But on that day in 2000, in a small house that I couldn’t afford in a country really far from home, I read about a writer who was, if A. S. Byatt was to be believed, “the best, possibly,” and had become so on her husband’s small income, and who had demonstrably not wasted her life raising three children and staying married during challenging times. Fitzgerald’s story was both permission and company; it was okay if I too had to start late and move slowly as a writer. And with each new challenge that came to me after — financial hardship, war, the failure of a marriage — I could say to myself: Penelope Fitzgerald was here too.

¤

In the opening scene of Offshore, we are introduced to an assorted and motley crew of riverboat owners who live on Battersea Reach on the River Thames in London. Or, rather, we are confronted with them. There is no expository introduction, not even of the best, briefest kind. (As in “It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn’t know what I was doing in New York.” Or, “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.”) There isn’t any landscape or setting or description of the Thames, or its estuaries, or of London in the 1960s. The novel simply starts — and starts hard. Are we being asked to do something dishonest? says someone called Richard, and there you have it. Done.

The fantastic precision of Fitzgerald’s prose is one of the qualities her fans prize most, second only to the wry, sad, desperately appealing characters that populate her books. Her novels all come in at about 150 pages, and there’s not a spare sentence in any of them. She has the syntax of a warrior poet, each phrase forged to its glittering essentials. Hermione Lee, writing about Fitzgerald’s collected essays, The Afterlife (2003), noted that, “she likes her readers to have their wits about them.” Reading Fitzgerald is a contract of mutual respect. Fitzgerald will not elucidate. The reader will get it and rejoice. Or not, if that’s what she wants.

Most of Fitzgerald’s characters are artists, self-identified or not, and the author is unflinching in the way she uncovers their oddities and misguidedness, but also skilled in making us love them anyway. (In her nonfiction, Fitzgerald also centers on self-identified artists, as in her biographies of Edward Burne-Jones, a thriving and long-lived painter associated with William Morris and the Aesthetic Movement, and Charlotte Mew, a sensitive, suicidal poet associated with the Bloomsbury Group.) The novels feature child actors (At Freddie’s); a failed violinist, Nenna James (Offshore), and the poet Novalis (The Blue Flower). Close in spirit to these are the book-loving Florence Green in The Bookshop; Frank Reid, the abandoned husband in The Beginning of Spring, who practices both printmaking and fatherhood with idealism more befitting an artist than a businessman; and Fred Fairly, protagonist of The Gate of Angels, who is a physicist dwelling, whether he wants to or not, in negative capability, placed as he is between belief and unbelief, science and ghosts. Fitzgerald distracts us with stories of dreams that end in failures and half-failures, while simultaneously conjuring a surprisingly certain faith in the losers and their causes.

Of all her books, Offshore offers the best example of this duality. Everything that can go wrong does, and yet it is funny, surprisingly romantic, and leaves you squarely on the side of the losers. At the center of this is Nenna, who can’t care for her children in the way she wants, can’t make a living as an artist, and is haunted by an internal “conscience courtroom” in which a judge condemns her for failing in her marriage. At the same time she’s having enviably cool late-night conversations with her gay best friend, Maurice, who becomes, in those small hours, “an oracle, ambiguous, wayward, but impressive”; gets rescued after her failed attempt to reconcile with her husband by a cab driver who calls her “Sleeping Beauty”; and goes boating in the moonlight with Richard, whose “Johnson came to life at once” just when it was most needed.

Maurice works as a prostitute, his boat is being used for felonious purposes, and he is able to do nothing to improve either of these situations. At the same time, he is often the one who sees to the needs of the older houseboat dwellers, making repairs, running errands, and being “tenderly responsive to the self-deceptions of others.” He’s also in possession of one of those endearingly misguided artistic temperaments. He creates a “Venetian corner” on his boat — a “feature” made of mauve lighting, paving stones, and white, red, and gold paint that thrills the neighbors and is the scene for some of the novel’s best dialogues. Tilda, the younger of Nenna’s daughters, is the scene stealer, having “the air of something aquatic, a demon from the depths” about her as she sasses the nuns at her school, chants the tide charts, mudlarks with her sister, Martha, sitting atop a mast, casting her wry commentary to the waters. Offshore is one of the saddest books I’ve ever read, and it has the characters that in all of literature make me the most happy.

¤

Deciding to write Offshore, the movie, started, I think, as an exercise in fan fiction. I wanted to spend more time with Nenna, Maurice, Richard, and Tilda. I wanted to see them onscreen in the way that I could see other beloved book characters, by dialing up Masterpiece Theatre, for instance. I wanted to see the inside of Nenna’s houseboat on the River Thames, and hear an actress deliver Tilda’s one-liners. The book was so good, I wanted three dimensions.

I also started writing the screenplay because I was in love — passionately in that amphetamine way that makes you think you can do anything. In the book, Nenna James is described as having fallen in love “as only a violinist can,” and Fitzgerald intimates that she and her husband had not, perhaps, given “sufficient time to think things over before they married.” I related to that — the bomb-gone-off falling in love so hard you can’t think straight, and also the helplessness that comes after the blast, when the challenges begin. And, as it happened, my new love was a filmmaker and a bit of a hustler, and had, almost at my first mention of wanting to make a film about this book I loved, found the telephone number of the book’s rights holders and discovered that they were indeed available.

The literary executor of Fitzgerald’s estate — the keeper of the book’s film rights — turned out to be Terence Dooley, one of her two sons-in-law. Terry was married to Tina, whom, Brian and I soon discovered, was the inspiration for Martha James. Tilda, we learned, was based on Tina’s real-life sister, Maria. (Fitzgerald’s son, Valpy, isn’t in the book but is echoed in the character of Heinrich von Furstenfeld, a young man of “good European background,” who is based loosely on one of Valpy’s visiting friends.) Terry, when we first spoke to him, was just back in England after working with Fitzgerald’s papers at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas. We learned that just a few years before she died, Fitzgerald had told him in passing “almost as a tease” that he was to be her literary executor and that it had never been discussed further. (Lee provides a clue to the choice when she describes Terry’s entry in the family in 1970. He was then “a long-haired poetry lover […] a passionate reader and a compulsive book-buyer, imaginative, unworldly, serious, creative with two literary siblings,” and he and Tina had met at a poetry group at Oxford.) His first big project as executor was to catalog Fitzgerald’s papers.

When we met Terry, he was in the most challenging phase of this project. The author often did not bother to date her notebooks and letters, and family members and friends had not always saved the envelopes in which correspondence arrived. When she sold the first batch to the HRC, she simply dumped them into boxes in what Terry describes as “a chaotic state.” The job of ordering this body of work meant using context clues to figure out not only when they were written, but in some cases where they were written.

So Terry was right then knee-deep in the good stuff — pulling together what he needed to bring Fitzgerald’s collected letters together into the book So I Have Thought of You (Fourth Estate, 2010). The finished collection captures two quite distinct sides to her character — the loving, funny, self-effacing Ma and Mops of the personal letters, and the intellectual, detail-oriented, and generous Penelope of the professional correspondence. A. S. Byatt wrote the preface to So I Have Thought of You, and in it she tells a story that reveals a great deal about Fitzgerald’s expectations for her readers. Fitzgerald, we learn, let Byatt know that she felt that the reviews of Human Voices (1999) failed because they didn’t note that the book was based on the German poem “Der Asra,” by Heinrich Heine. Byatt, who was one of these failed reviewers, confesses to being nonplussed. She says, “I hadn’t noticed that [allusion], and I don’t know how she expected anyone to do so.” Still, up for the challenge, Byatt went back to “Der Asra,” reread it, and was enlightened. It was then, she says, that she “saw that Penelope Fitzgerald was not an English lady writer […] but someone with an austere, original talent, unlike anyone else writing in this country at this time.”

Terry’s introduction to So I Have Thought of You follows Byatt’s preface, and you won’t find a better short biographical sketch of Fitzgerald anywhere else. It is a fine piece of writing in its own right, providing both a concise life history and a few personal reminiscences that shed a light on both Fitzgerald’s personality and as her artistic influences.

The publication of this book was an important time for Fitzgerald’s literary legacy. She was becoming more known in England and America, and Terry was overseeing translations of her books for other countries. Yet with us, Terry remained an elegant and generous correspondent, and from the beginning we traded book recommendations, our own original poems and writing, and, of course, drafts of the emerging screenplay. As Terry’s editorial work progressed, he sometimes sent photocopies of Fitzgerald’s hand-written letters as he found them, often with bits and pieces of context, unfolding a much more personal portrait. Once, during a weekend meeting in Paris, Terry told us the story of finding and reading the proof of The Bookshop one evening when Fitzgerald was out — how he read it in one sitting, and in so doing realized a very great talent was living under his roof. The story is now in the introduction to So I Have Thought of You. Terry writes, “I immediately wrote her a note to express my amazed and delighted appreciation; it would have been too embarrassing to confess in person.” He told us that Fitzgerald never referred to the note he had written, but she had saved it; he had come across it over the course of his research.

No Fitzgerald bio had yet been written, and it was through Terry’s stories about Fitzgerald’s real-life houseboat experience that we came up with the ideas we needed to transform the book into a screenplay. The fact that it was Fitzgerald’s own boat, Grace, that sank and not the fictional neighbor’s boat, Dreadnought, gave us the idea we needed — to give Nenna a storyline closer to Fitzgerald’s own. In our version, Nenna loses her boat and has to find a place for her and her girls to live; this solution made us feel we’d preserved the truth of both the novel and the writer’s reality.

The biggest challenge for us was the novel’s ending, or rather its lack of one. Its last page leaves its characters, literally, in midstream. Nothing is resolved for Nenna despite her efforts. Nothing is resolved for anyone, actually, not even enviably strong and resourceful Richard. We considered, briefly, drawing again from real life. After their houseboat sank and all of their possessions were lost, Fitzgerald and her family ended up in a homeless shelter for women and children for several months before being given more permanent government housing. For the screenplay, though, we stuck to fiction. In our version, Maurice comes to the rescue — we just couldn’t resist a Hollywood ending.

Perhaps we were trying to create a happy ending for ourselves, as well. I’d stopped trying to work as a writer when my own family hit bottom because of the dot-com bust and subsequent economic freeze after 9/11 — a double whammy that left us unemployed and homeless for several months. Then, when my husband was deployed to Iraq during the second Gulf War, my marriage broke apart, leaving me guilty, on my own with my children, and in desperate need of financial stability. I figured I was done with writing forever. But then I met Brian, and we began building things again. We were talking about blending our families and inspiring each other as artists. I was hanging on, a little bit like my hero, Penelope Fitzgerald, had, holding children and home together, and keeping a flicker of a literary life alive in bits and pieces. By the time we persuaded a Hollywood producer who was a college friend of Brian to teach us more about the filmmaking craft and sign on as producer, I was almost forty, and I knew that any time was a good time to start a book or a movie script.

¤

When Terry told us that Hermione Lee had signed on to do the biography, my reaction was, well, of course. Who else should write the biography of one of the greatest late-20th-century authors than the celebrated biographer of Virginia Woolf and Edith Wharton? By the time Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life came out, I already knew the full story — between the collected letters, Penelope’s memoir of her family, The Knox Brothers, and our friendship with Terry. And yet, the biography read like a thriller, opening with a scene of “hectic activity” in the winter of 1916, when the world is at war, refugees are being seen to, and fatal illness lurks all around. Into the midst of this Penelope Mary Knox was born, and things really never did settle down.

Lee makes ingenious use of the way Fitzgerald essentially wrote her way through her own history. Fitzgerald’s own biography of her famous father and uncles, The Knox Brothers, was a key source and helps Lee avoid the usual 100 or so odd pages devoted to juvenilia at the front of most biographies. (Lee cites Fitzgerald’s biography of poet Charlotte Mew, as well as that of her family members, as an influence in her 2013 Paris Review interview.) Instead, we get Fitzgerald’s childhood between wars, her college and war years, and her early marriage interspersed with close readings of the corresponding book that was inspired by these events. Each phase of her factual life is, in this way, crossed with its literary counterpart — a bit like hanging life drawings next to an oil painting. Then, at just the right moment — two-thirds of the way through — Lee changes the structure. Now, Fitzgerald’s last great works, the ones less obviously connected to life events, are brought out alongside deep research into her writing craft. Here are the insights culled from notebooks, interviews, essays, and letters detailing the sources and inspiration for her books.

I ordered Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life from England in the autumn of 2013, about a year before it came out in the United States. By this time, her following had grown substantially since the days of our mutual admiration society with Terry Dooley: more translations were in the works, as well as theater adaptations and several other film scripts, and her reading audience continues to grow. Terry told me only recently that they are preparing, for the archive, the original uncut manuscript of The Golden Child (devotees, please take note). But reading the book took me right back to the days when Penelope Fitzgerald and her dopplegänger Nenna James had lifted me from despair to determination. It wasn’t long before I dusted off the screenplay, rounded up my husband and our producer, and dug in again.

¤

Lee’s book is a deserving success, making The New York Times’ top ten for 2014 and acquiring a long series of accolades both here and in England. I think it’s interesting how frequently the reviews mirror the cultural and class bias that plagued Fitzgerald during her life. The often contemptuous treatment of Desmond Fitzgerald is one example: “the name of the catastrophe was Desmond,” says Philip Hensher in The Guardian, tempting me to retort, “umm, no, the name of the catastrophe was World War II and its economic and social aftereffects.” Lee’s research covers quite expansively the complexity of Fitzgerald’s marriage, the good and the bad. Desmond Fitzgerald’s drinking-related troubles were certainly drivers of the family’s descent into poverty, and most reviews took note of the fact that Fitzgerald slept on the couch for the rest of the marriage after the houseboat sinking. At the same time, Lee documents what was clearly an ongoing and tender relationship. The couple wrote letters to each other to the very end. “Every day & every year, I love you more, if that were possible, but it is,” writes Desmond in 1972, not long before his death. They took trips together, and perhaps most significantly raised three successful children. The biography describes the way the couple worked to educate Tina, Valpy, and Maria, traveling with them, tutoring them in their school work, and eventually sending all three to Oxford, thereby continuing on the tradition of their mother, father, and grandparents. As to what clues about the couple lie in the decades worth of letters, notebooks, and other papers that went, with the Grace, to the bottom of the Thames, Lee rightly does not speculate.

The common perception that Fitzgerald was intentionally reticent and that her life is difficult to understand is frustrating. James Wood, reviewing Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life for The New Yorker, describes a story “crossed with wounds” that “cannot speak,” chiming in along with most of the others about an inscrutable author and her mysterious late start. The prevalence of the idea that Fitzgerald’s story is hard to understand in so many of the reviews calls to mind C. S. Lewis’s Professor at the beginning of The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe — that master of logic who cannot fathom why Peter and Susan are still confused about their sister Lucy’s bizarre tale about a faun and a wardrobe and a world without Christmas. “You know she doesn't tell lies and it is obvious that she is not mad. For the moment then and unless any further evidence turns up, we must assume that she is telling the truth.” I believe that Fitzgerald’s truths are right in front of us — we’re just asking the wrong questions.

So let’s start, then, in a better place. Start with another, different, Guardian reviewer, Robert McCrum, who can at least see that the biography (and the life it describes) “holds up a cracked mirror to its century.” Here is one very plain answer to the “mystery” of Fitzgerald’s late start: two world wars, a postwar economic boom and bust that wreaked havoc on the middle class, the tumult of the 1960s, and having been born just the right year to make sure she was at ground zero for all of it.

Next, let’s consider the question of “reticence.” Lee describes an “outpouring of ideas in the late 1970s [that] was astonishingly energetic, rapid and profuse.” Alongside the almost simultaneous publication of The Golden Child and The Knox Brothers in the autumn of 1977, Fitzgerald started at least five books: two novels, a book on Renaissance painting and flowers inspired by her work on Burne-Jones, and two biographies. Given a bit of an income, a room to write in, and the time to do the writing, Fitzgerald had plenty to say. And if the media didn’t know how to talk with her, it was not because she was hiding. She went to awards ceremonies, served as a Booker judge, gave interviews, and managed her publishers all on her own and quite competently. She was modest, says Terry, “but she didn’t go around being a Miss Marple figure, that’s a myth based on people’s cliché idea of old ladies.” Her own description of her situation as being an “old writer who has never been a young one” is quintessentially cogent. Although she wrote in one way or another most of her life, she didn’t grow an audience over time like most writers.

Still, the questions persist. When asked whether or not the “women’s lot” had been one of the reasons for her late start, Fitzgerald replied, “Well, I don’t know as it did, really. I feel I ought to know, but I don’t” — which is about as good of an answer as the question deserves. Of course the “women’s lot” was one of the reasons she had a late start as a writer. A better question might be, “how did she manage to survive her woman’s lot and live to see her vocation fulfilled where so many women did not?” Or, “What is wrong with society that a mother cannot very easily make an earlier start?” Virginia Woolf might put it this way: if Shakespeare’s sister had put down her mending, ignored the bit about poodles dancing and women acting, and gone on anyway instead of killing herself one winter’s night, would we wonder why she was so late to the opening?

¤

In her New Yorker essay, Joan Acocella asks the question, “Why do we bother to interview artists? Why expect them, in two hours, to tell us their story?”

The answer to her question is that we want to know how they do what they do.

We want to know how artists lift up the ordinary and make it beautiful. We want to know their rituals — the hour they get up, the number of words per day that they write, and whether they write with pencil or pen, and what they have for supper because we think knowing these things will raise the veil. The cool thing about Penelope Fitzgerald — the reason why her story has sustained me for a decade and a half — is that of any writer’s life, hers is, in some ways, the most usual, the one most like yours and mine, despite the eccentricity of living on a houseboat. She never had a room of her own, she didn’t have a dramatic mental illness or mid-life sexual crisis, she kept her day job, stayed married, raised well-adjusted children, was polite to passersby, and almost certainly used whatever pencil was at hand.

Here is what we know about the genesis of Penelope Fitzgerald’s first novel: Not long after her husband’s death, she went, by herself, on a package tour of China. She woke early in the mornings, Hermione Lee tells us, and “not wanting to disturb her room-mate, Miss How, she turned ‘My China Diary’ upside down, and, at the back of it, began to write The Bookshop. The first scene is rapidly and quite fully sketched in, as if springing onto the page.” When she returned home, she finished the novel in a few weeks time.

There is no mystery. The answer to the question of Penelope Fitzgerald is here in front of us, hiding in plain sight. She was born to write, started when she could, with the materials that were at hand, and never gave up her laser focus on that which is true, enduring, and beautiful.

¤

LARB Contributor

Courtney Cook has written for Salon, The Washington Post Book World, The Huffington Post, More, and others. Her current book–length work is a memoir of motherhood, madness, and poetry. She is online at @courty and courtneycook.us.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Pride and Paragon: Listening to George Eliot’s “Middlemarch”

Laurie Winer reviews the Audible.com version of George Eliot's "Middlemarch."

Listening to George Eliot’s “Middlemarch”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!