Open Season on Husbands: Female Revenge Movies of the Long 1990s

Isabelle Lang and Laura Valenza revisit the 1990s feminist revenge plot and its bearing on today’s domestic violence laws.

By Isabelle Lang, Laura ValenzaNovember 25, 2022

THE LEGENDARY ENDING of the 1987 movie Fatal Attraction stages an epic showdown between homicidal maniac mistress (Glenn Close) and the married man who wrongs her, replete with jump scares and twists, finishing with a literal bang. The wife returns to shoot the mistress in the chest, saving her husband and her marriage. In the 1980s, the danger to the family came from the work-obsessed career woman. But what if, instead of pointing her pistol at the other woman, this wronged wife aimed at the lying, neglectful husband?

Welcome to the 1990s, where we see a new focus on a fundamental feminist issue: safety and bodily autonomy. While ’80s flicks like Working Girl (1988) and Baby Boom (1987) show ambitious female leads trying to have the mythical All, the ’90s hail in a back-to-basics decade of women just trying to survive.

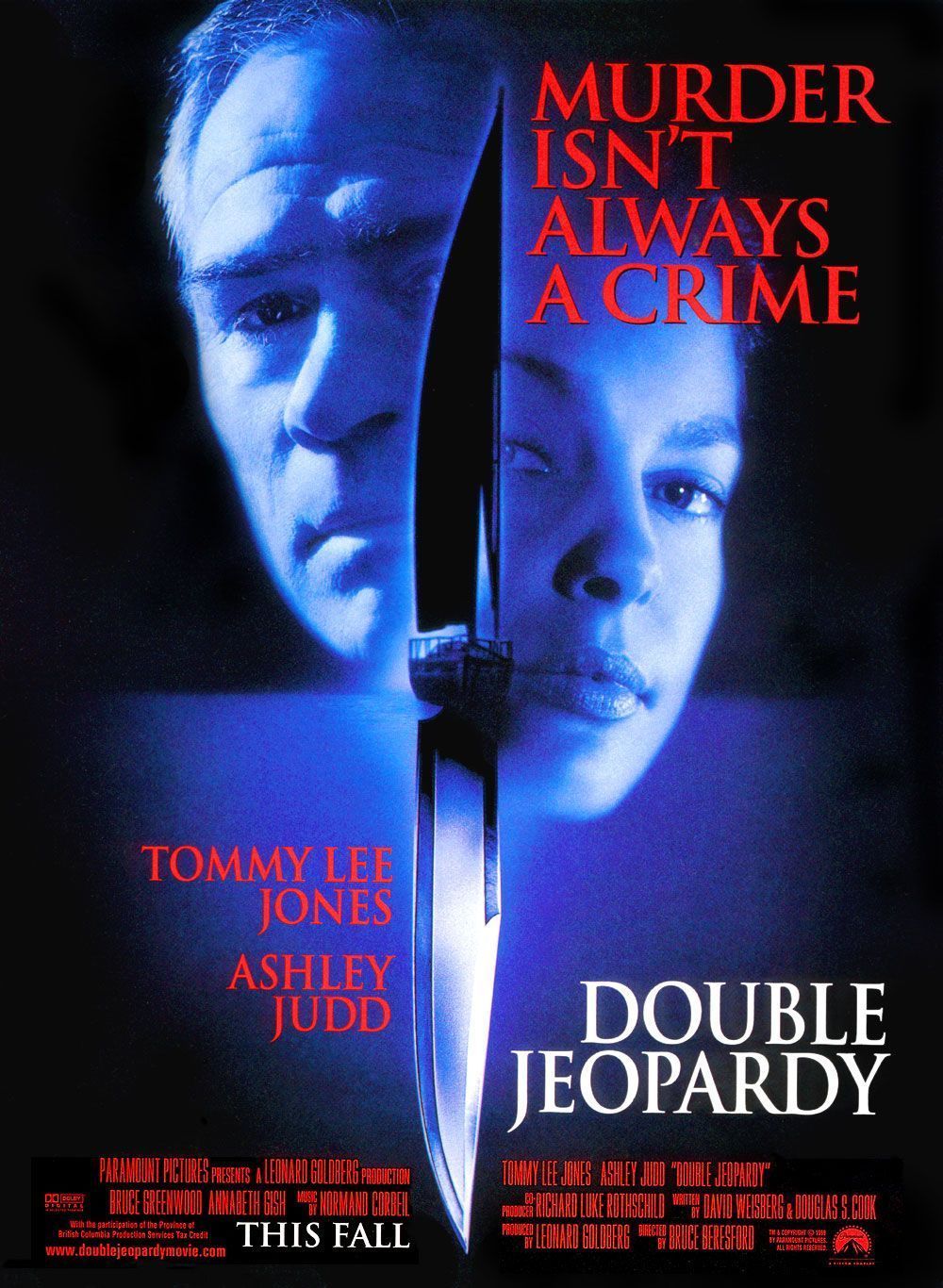

In that sense, thrillers like Sleeping with the Enemy (1991) and Double Jeopardy (1999) share something in common with the cult classic romance Practical Magic (1998) and the comparatively highbrow Thelma and Louise (1991): they are all about women who murder their abusers. Broadly, these movies represent “the female revenge plot” in which women seek vengeance against the (usually) men who have abused or oppressed them.

Sleeping with the Enemy and Double Jeopardy may fall into the female revenge genre, but, like many other films in that category, their protagonists’ revenge — or, in some cases, self-defense — is motivated by a need for freedom and security within a justice system that has failed them.

Films like Sleeping with the Enemy, Double Jeopardy, and other ’90s female revenge plots also followed a decade of both major legislative achievements and failures for women. In a revised edition of her influential 1980 book Women Who Kill, Ann Jones details the landmark 1983 Connecticut Supreme Court decision that ruled that a group of officers who refused to arrest an aggressive spouse — after dozens of repeated distress calls and violations of a restraining order that ended in a violent attack — had denied the victim “equal protection of the laws.” Conversely, a 1980 Georgia case (also referenced by Jones) ruled against the battered woman’s self-defense killing of her abusive spouse because, as one juror said after the trial, “We couldn’t let her go. It would have been open season on husbands in Atkinson County.” These female revenge movies of the ’90s expose and dramatize the failings of the system from a decade before, ones that led real women to pull the trigger on their abusers.

¤

Rife with campy B-thriller and romance moments, Joseph Ruben’s Sleeping with the Enemy seems like an easy movie to dismiss. Critics at the time called it exploitative (looking at you, Roger Ebert) or “skin-deep,” as Janet Maslin wrote for The New York Times. But the movie’s popcorn sensibility only speaks to its effectiveness in communicating changing societal values to a broader public. This is a movie about a woman seizing power by any means necessary.

Sleeping with the Enemy follows Laura (Julia Roberts), who lives what seems like a charmed life with her wealthy husband, Martin (Patrick Bergin) — until he hits her. Martin’s success as an investment banker goes from enviable to terrifying, and all the couple’s status symbols — their lonely and cold modern house on the beach, Laura’s phony and manicured beauty, Martin’s intimidating business suits that cannot be soiled or dirtied in any way — speak to the inequality in their relationship. Trapped and terrified, Laura must fake her own death to get away.

The tone of the film shifts when Laura starts life anew in an idyllic small town, where she moves into a warm, quaint bungalow: a room of her own. She lets her hair down and starts wearing blue jeans. Her handsome neighbor, Ben (Kevin Anderson), helps her get a job, and their friendship buds into romance. Meanwhile, Martin gets wise to Laura’s escape and begins to track her down.

At first glance, Laura’s new life plays into a white middle-class American dream: the small town where everyone is neighborly and nice, the fairy tale cottage, the sweet-tempered boy next door. Their romance is even solidified by dancing to a wholesome 1950s American Bandstand bop.

But, in fairytales, as in real life, if it’s too good to be true, it is. This small-town cottage, complete with matching small-town love interest, is not the typical home of white picket fantasies. Laura and Ben’s love theme, Dion’s “Runaround Sue,” offers a sharp reminder of how popular culture’s conception of romantic love is shot through with possessiveness and misogyny. And we know that Laura’s new life is precarious, her happy ending far from over. While the film borrows cheery elements from the rom-com, it’s not about love or happily-ever-afters. It’s about the price of freedom.

The film ends: villain slain, cue the embrace. Still, the last shot does not give off the proverbial riding-off-into-the-sunset vibes. Instead, the camera pans to Martin’s dead body. We can appreciate the assurance that the monster is dead. But wait. The camera pans back to his limp hand, to the glistening band on the ring finger and Laura’s own wedding band glittering on the floor, just out of Martin’s reach. The last shot reminds us that Laura’s happiness comes at a dangerous price — the violent destruction of a failed marriage. We also get a devastating glimpse of the realities that lurk behind the white picket fence, the posed family photograph.

Laura’s freedom could not be attained through wealth, social mobility, or the law; multiple times Laura says the police can’t help her. It is only the death of the Master of the Universe that can save her life, and we sit at the edge of our seats, rooting for her to pull the trigger.

In 1991, despite the lukewarm-to-negative reviews, Sleeping with the Enemy hit number seven at the domestic box office, earning a whopping $94 million. In places one through six sat Terminator 2, Robin Hood, Home Alone, The Silence of the Lambs, City Slickers, and Dances with Wolves — all of which, except The Silence of the Lambs, featured male leads. Fresh off her star-making role in Pretty Woman, Roberts proved she was a box office princess who audiences could root for, whether she was being rescued or having to do the job herself.

¤

At the time of its release in 1999, Ashley Judd and the cast of Double Jeopardy didn’t fare much better than Sleeping with the Enemy. The movie was met with the only thing worse than staunch criticism: middling reviews. While the San Francisco Chronicle lauded its “intelligent grasp of the moment-to-moment emotion,” others dismissed it as forgettable. Box office numbers from the year suggest otherwise: Double Jeopardy remained at the number one spot for four weeks, ousted only by the release of another action film/psychological thriller, Fight Club (1999).

Double Jeopardy tells the story of Libby (Ashley Judd), who is falsely convicted of her husband Nick’s (Bruce Greenwood) murder after he fakes his own death, fleeing the state (and some hefty embezzlement lawsuits) with their child and his new girlfriend. In prison, Libby waits and listens and learns how to appeal her case. She discovers the legal precedent of “double jeopardy”; since she cannot be tried for the same crime twice, what’s to stop Libby from killing Nick upon her release? Enter stage left: Libby’s tough and quick parole officer (Tommy Lee Jones) to bring her back into the fold.

For a film that so many people saw at the time, it has generated surprisingly little criticism and chatter, then and now. The most common conversations involve fact-checking the film’s use of the term “double jeopardy.” For the record, Libby could not have shot her husband in the middle of Mardi Gras without any consequences just because she had technically already been prosecuted for his murder. (And for those of us without JDs or severe Law and Order habits, no, she likely wouldn’t have been convicted of murder in the first place without a body.)

But we don’t go to the movies for the facts — most of us go for the feelings. We go to be told stories that reflect the things we feel and even dread for ourselves. As the box office numbers demonstrate, viewers went to confirm that Libby’s fears (and those of too many other heroines of the female revenge plot) of losing her child, her autonomy, her body, herself at the hands of a dangerous spouse and an indifferent state apparatus, felt very real. The rewriting of the double jeopardy law is admittedly over the top, but instead of laughing it off as a dumb plot device, we might see it as a comment on the miscarriage of justice upon which the female revenge plot turns. Naturally, this is not “how double jeopardy works,” but what if, for once, the United States’ laws benefited the misused woman instead of the powerful man? Wouldn’t that be great? Wouldn’t that be absurd?

¤

Noticeably absent from the female revenge films of the 1990s are women of color triumphing over their abusers. If we operate according to cultural theorist Jeremy Gilbert’s theory of “the long ’90s,” then Enough (2002) turns our double bill into a marathon. While it’s always empowering to watch J.Lo kick butt in a movie, the film goes out of its way to avoid explicitly examining the intersection of race and domestic abuse.

In Enough, Slim’s (Jennifer Lopez) fairy tale marriage to Mitch (Billy Campbell) turns sour when she confronts him about his infidelity, and he beats her. Mitch believes since he’s the breadwinner, he calls the shots, but, by film’s end, Slim finds her own strength and kills him, freeing herself and her young daughter from his control. In an early scene, Slim seeks advice from a police officer who essentially restates the same issues Jones highlights in Women Who Kill: almost nothing can be done without physical proof, and then what can be done isn’t much help. Slim feels like her only options are to file charges, antagonizing Mitch in the process, or to run.

In addition to the advantages Mitch has because of his wealth and his gender, he wields the weapon of whiteness in his power over Slim and the people she loves. In a pivotal scene during which Slim’s friends try to sneak her and her daughter away in the night, Mitch assaults the entire group, holding a gun to Slim’s chosen father Phil (Christopher Maher), calling him a “rug head” — the only specific reference to anyone’s racial or ethnic identity throughout the whole movie — and asking him whom the police would actually believe if called to the scene. Phil and his relatives are made into generic “others” in the film: Slim’s daughter is skeptical about their food that is different from what she is used to, but these cultural differences are not explored in any meaningful way.

As with Sleeping with the Enemy, critics called Enough “exploitative,” a big-budget version of the Lifetime channel’s treatments of real social problems. But the stories of these bloody-knuckled women who share bone-deep fears aren’t as superficial as they might seem. These movies were all directed by men, and written almost entirely by them as well, but they still tell stories too often ignored or overlooked and offer an understanding of how the cultural conversation can shift through mainstream narratives. And the female revenge plot benefits greatly from the participation of women, nonbinary, and POC artistry on all levels, not just on-screen but also in the making of the stories, as we see in the strength and power of Callie Khouri’s screenplay for Thelma and Louise. But as Louise states sadly and perfectly early in the film: “We don’t live in that kind of world, Thelma.”

Still, could we? In June, President Biden signed into law what

he called the “most significant” gun legislation

in 30 years. One component of this law removes the “boyfriend loophole,” and, according to NPR, “That means dating partners convicted of domestic abuse will no longer be able to purchase firearms, rather than just spouses and former spouses.” If legislation continues to incite radical filmmaking, we could start to see a cycle of smarter, angrier, unabashedly feminist revenge films in the 2020s, already ushered onto the scene by the award-wining Promising Young Woman (2020) or the unapologetically brazen Gunpowder Milkshake (2021). And if the films continue to react to and expose the world as it is, maybe one day we can live in that kind of world.

¤

LARB Contributors

Isabelle Lang is a writing instructor, editor, and poet whose work has appeared in Beecher’s Magazine, Rat’s Ass Review, and elsewhere. She currently lives and teaches writing in Southeast Louisiana.

Laura Valenza is a co–film editor at the Brooklyn Rail, and a writer and editor at the School of Visual Arts. Her film criticism and fiction also appear in Lit Hub, Gulf Coast, Cream City Review, and elsewhere.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Avenging Goddess of Screenwriters: Remembering Mary C. McCall Jr.

J. E. Smyth commemorates a landmark anniversary of forgotten screenwriter and guild president, the sharp-tongued, blacklisted Mary McCall.

Weird Wild West: On Jordan Peele’s “Nope”

Jacob Walters discusses Jordan Peele’s “Nope” in the context of Westerns and Black film.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!