On Its 40th Anniversary: Notes on the Making of All the President’s Men

In time All the President's Men revealed its theme to us — what John Huston called “the bell that rings in every scene.” This wasn’t just a movie about the reporters’ need to know.

By Jon BoorstinMarch 25, 2016

IF YOU HAVE WORKED in the movies, you know that a picture as good as All the President’s Men is a miracle. An impossible conjunction of talent and opportunity, collaboration and ego, trust, power, and luck. And then more luck.

As the critic Pauline Kael said, Robert Redford liked to make “how to” pictures: how to be a political candidate, a mountain man, a downhill skier. Smart, credible low-key films, free of Hollywood bluster and pretense. Captivated by Woodward and Bernstein’s Watergate articles in the Washington Post, he wanted to make how to be an investigative reporter, to bare the dogged reality, enshrine their relentless drive. Perhaps he wouldn’t even act in it.

Back when thick bricks of wood pulp were dropped on our doorstep, the highest praise for a movie star was “so powerful he could get the studio to make a picture from the telephone book.” If ever it applied to anyone, it was Robert Redford in 1974. But when he told the studios he wanted to make All the President’s Men, most of them said they’d rather film the phone book. It came down to Warner Bros.

Even Warner Bros. had its concerns. It pointed out that everybody knew how Watergate ended. Redford replied that the story wasn’t a whodunit but was really about two mismatched guys, a Republican WASP and a radical liberal Jew, on an impossible mission. After all, he’d made the ultimate buddy pictures of the decade, The Sting and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and the quintessential WASP/Jew mismatch The Way We Were. But that had Barbra Streisand, Warner Bros. said. Where’s the girl? Where’s the gun? “Newspapers, typewriters, telephones, un-unh, Washington, un-unh.” So the man who’d made the CIA nail-biter Three Days of the Condor told them it was a procedural thriller: how two relentless cub reporters slipped the grip of the most powerful man in America to bring him down.

Still, Warner Bros. wasn’t convinced. Everybody not only knew how this trauma ended, they’d lived every twist and turn, a tangled mess that studio lawyers insisted must be scrupulously accurate. Warners confirmed its worries with market research. They learned that half the audience expected a hatchet job and was primed to hate the picture, and everyone in America was fed up with the story and eager to move on. Imagine where they’d be when it finally came out a year from now.

But Redford was Redford, after all, and to sweeten the deal he threw in Dustin Hoffman, the only nerd with phone book heft, hero of the mismatched WASP/ethnic classic Midnight Cowboy. Also their favorite buddy-story scribe William Goldman, who’d crafted Butch Cassidy, to write it.

Redford wanted the messy truth. He searched for a director who could deliver gritty New Wave realism. He approached Hal Ashby, who’d just drawn a brave, honest performance from Jack Nicholson in The Last Detail. Alas, Ashby was not the right kind of gritty; his scruffy drug-inflected manner did not mesh well with the khakis-and-necktie world of the Washington Post. Redford had to go another direction. So he hired a Yale grad who’d prepped at The Hill School, who wore not only khakis but a blazer, whose idea of rakish was a kerchief knotted around his neck.

Alan Pakula was 46, but already considered Hollywood old guard. He’d produced To Kill a Mockingbird, and as producer he’d hired the fledgling Redford a decade before for Inside Daisy Clover. This is not a common pedigree for a successful director. A good producer’s talents are more managerial than inspirational, and Pakula had made a point of staying out of his director’s way. But the remote-control charms of producing had worn off. As Pakula told it, one morning on the first day of shooting a picture he found himself in Saks buying shirts, and thought, “This is ridiculous.”

So he’d hired himself as director, and he coaxed the neophyte Liza Minnelli through an Oscar-nominated turn as a vulnerable kook in The Sterile Cuckoo. Then he guided Jane Fonda’s Oscar-winning role as a high-priced call girl trying to quit in the taut murder mystery Klute, and Warren Beatty as a reporter tracking the paranoid assassin in The Parallax View. Good qualifications for a performance-driven political thriller, in a man who could hold his own with Ben Bradlee over lunch at Sans Souci.

I was hired as Alan Pakula’s assistant. My duties were undefined. I’d been his AFI intern on The Parallax View for $50 a week. He’d been comfortable around me and I’d been useful enough to the movie that he’d kept me on after shooting to help with post-production. This time I could actually get paid.

Pakula brought the best of the old school sensibility to the project. He pulled Redford away from his idea of copying the reality of a certain kind of documentary. This could never be a documentary, he said, and even if it could nobody’d want to watch it. Hollywood has made an art of elevating the mundane. That’s what movie stars do for a living, make the everyday transcendent. Grab what you’ve got. Don’t dye your hair. Use being Robert Redford. Watergate was an epochal moment for America. Let’s feel its importance in every frame. Yes, the audience had to believe. But it also had to be transported. That was Hollywood’s art form.

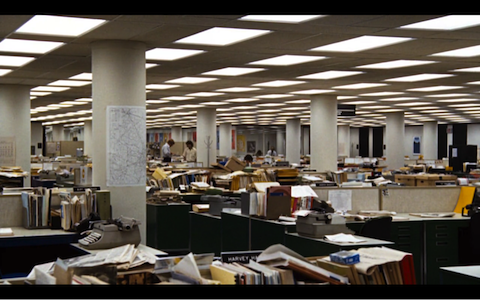

But first they had to believe. How do you convince them? Using the exact shade of institutional orange for the desks in the newsroom actually makes a difference. The actor believes in the film’s reality that little bit more. The viewer relaxes his guard. Pakula and Redford decided to capture the football field–sized newsroom in precise detail. We built its duplicate on a Warner Bros. soundstage, decorated with trash transported from the real one in Washington. The press made much of this.

Our designer George Jenkins was a courtly gentleman who’d done Pakula’s other pictures and been an art director since The Best Years of Our Lives in 1946. But this film required a new sort of look, a literal reality. We had desks for 160 journalists (the actual pressroom held 180), and Jenkins wanted each workplace to reflect the personality of a specific reporter. He could count on George Gaines, the set decorator, to come up with 20 or 30 reporter personalities, but then he’d start repeating himself. It would feel phony. So Jenkins had a simple solution. He took a picture of every desktop in the Post newsroom. He printed them 8x10, stuck each one in the top drawer of its Burbank counterpart, and told Gaines to recreate it.

A big part of my job was helping Pakula make things seem real. To research the Watergate break-in that opens the picture, he sent me on a night patrol with the undercover cops who arrested the burglars. I heard their version of events and I wrote it pretty much as it appears in the picture. And they gave me what counted at the time for a real scoop:

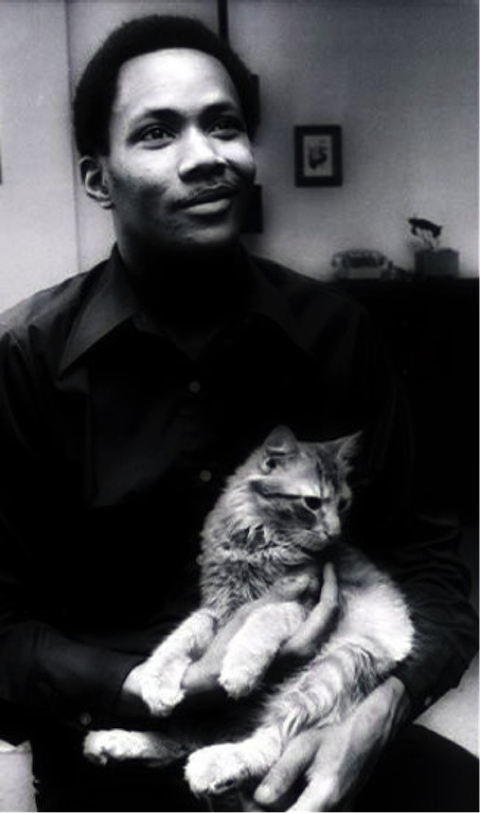

Imagine, if you will: The Watergate Myth as the press had created it started with the Telltale Tape. That was where our script began. Frank Wills, the African-American security guard at the Watergate complex (just about the only person of color in the story) spots a tab of tape sticking out beside a doorknob at a stairway entrance. He examines it. Aha. Someone has taped the lock open. Break-in. They’re still inside, or the tape would be gone. He thumbs his walkie-talkie. Detectives appear. That little piece of tape and this quiet, sharp-eyed man bring down a President. Without his eagle eye the burglars would have done their dirty work and Nixon would have ruled untroubled. He has preserved the commonwealth. Aren’t we lucky we have legions of Frank Wills out there, making us safe.

The detectives found this version most amusing. The burglars after all were CIA trained. Any secret agent will tell you when you tape a door open, you always put the tape vertically, so it won’t stick out on the side and give you away. That’s how they did it. In actuality, there was no telltale tape, nothing for sharp-eyed Wills to see. His patrol beat took him right through the door. He’d have used his own key. He’d have been somnambulant not to notice it was taped open. A small difference, perhaps, but big in the world of fable. Wills’s supernal vigilance didn’t trip up Nixon, dumb luck did. If he’d walked through another door, they’d still be up there. No one’s watching over us. You just get lucky sometimes. What a story. I reported the truth to Pakula. We could get it right.

Here’s how the scene appeared in the picture. Remember, it’s made for the big screen. Frank Wills plays himself. We first see him tiny in long shot and side lit:

Pakula went with the Telltale Tape, and gave Wills one of the biggest close-ups in the picture. He said if we did it the other way, people would think we’d got it wrong. But what he meant, I think, is akin to what the reporter tells Jimmy Stewart in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, “This is the West, Sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

IMDB provides this bio of Mr. Wills:

In spite of his notoriety for his outstanding work as a security guard, he was unable to find continuous employment for most of the remainder of his life after his discovery of the Watergate break in. He lived in relative poverty until he died of a brain tumor in 2000.

¤

While there was never any doubt on set who was making the creative and financial decisions, this was an era when actors didn’t commonly take producer credit, and Redford did not break precedent. If All the President’s Men had won the Best Picture Oscar for which it was nominated, it would have been the competent, dutiful Walter Coblenz, not Robert Redford, who collected the statue. I had to interview with Coblenz to get my job. The screenwriter Joe Eszterhas, who wrote Basic Instinct, Showgirls, and a journalistic exposé narrated by President Clinton’s penis, has called me “very intellectual and prone to abstractions,” and I suppose he’s right. Walter didn’t know what to make of me, but I was Pakula’s choice, so what could he do about it? He did want one thing crystal clear: “There are no producing credits to be had on this picture. Don’t even think about it.”

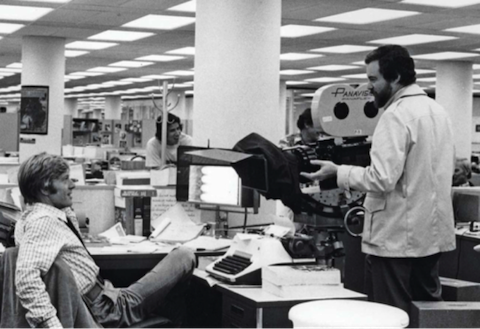

Redford had decided that a documentary on the making of All the President’s Men would be a valuable thing to have, shot vérité style — what All the President’s Men might have felt like before Alan Pakula — and Coblenz offered me the job of filming it. I’d just made a film on the Exploratorium, the museum of science and art in San Francisco, and one on the young Frank Gehry teaching architecture and town planning to fifth graders. If there had to be a camera following Redford around, Coblenz figured, might as well have it be someone who was already bound at the hip to the picture.

Quite an opportunity. My own film starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman. A tempting meta-subject, a truth-telling movie about the truth-telling movie of the truth-telling book. But I knew that if I stalked them with my Éclair on my shoulder, these film pros would shut me out from the unflattering, contentious, vulnerable situations when the picture really comes together. The meaningful stuff. Experts that they were, they’d give me just what they wanted me to have, and if I did somehow manage to dig deeper, Redford could take out whatever he didn’t like. Being the guy with a camera, I’d become a promotional tool.

But working on making the actual All the President’s Men was a different opportunity altogether. I’d be a part of Imperial Hollywood filmmaking at its best. I’d live it from the inside. I was 27, just old enough to suspect this opportunity wouldn’t come again. And yes, this was my chance to grab a toehold in the real movie business in case it could. I saw the big picture, and turned down “The Making Of …” They engaged Jill Godmilow, a fine filmmaker (Antonia: A Portrait of the Woman), but after she hung around a while she backed out too.

So I helped Alan make it real. I searched for video to play in the picture, I supplied Alan with Post articles for the dates of the scenes. Mostly, I hung around our newsroom, trying to look like Alan needed me, and watched. I befriended the repository of secrets, the script supervisor. She was tasked by the producers with keeping track of everything that happened on the set, and she kept careful notes for Pakula when the actors rehearsed. Silver-haired Karen Wookey was second-generation Hollywood, the daughter of actor Alan Hale, but she had the manners and diction of a Seven Sister. A calm, supportive presence, utterly reliable, thorough, and discreet. We got to talking.

A stopwatch around her neck, she timed shots and logged the day’s events. We spent more than 80 days on Warner Bros. stages, mostly on the Post set. Wookey remarked that when we were shooting at our Post, Dustin Hoffman would show up on the dot, saunaed and prepped, and Redford would arrive late. As his own producer, he answered only to himself. But when he showed, he came ready to shoot. “Let’s get on with it.” Hoffman, she said, was never in such a hurry. He may not be the producer, but he was definitely a star. He had to try things until he found his scene. A coincidence, perhaps, but Wookey noticed that Hoffman would improvise and experiment and prepare for however long that Redford had been late.

The only person who might break this pattern was Pakula. Isn’t that what directors do, bring discipline to their set? Wookey calculated that the combined lateness and retaliatory improvisation cost a week of shooting time. That’s an extra week of set costs, extras, crew, and production staff of at least 60. And if the crew is thinking about battling stars and the time they’re wasting morale collapses. All their work takes longer.

But Pakula didn’t make a fuss about it. He just rode it out with enthusiasm, patience, and good humor. He kept everyone focused on the work, and he turned what might have been a destructive battle of wills into a constructive collaboration. If his way added six days to the 60 on the set, you might call it a 10 percent overage to manage egos. The sort of thing I could never have captured in my aborted documentary, but Pakula’s essential contribution. That’s being a Hollywood director.

Rehearsals were private, but I had a glimpse now and then when one of the main players questioned the script. When scenes involved sensitive interviews, Pakula had to make sure the text was exactly as Woodward and Bernstein reported it. Goldman had kept it close to the book, but he sometimes added flourishes; he had a fondness of comradely raillery, and a penchant for the deft witticism to close a scene. Pakula and the actors stripped all that out. “To think when we’re done with this, Goldman will be the man who gets the envelope,” Hoffman said. And he did.

Our narrative defied the traditional rules of drama you see in, say, Spotlight. Here, personal lives weren’t part of the story. Shooting it, we didn’t quite believe it ourselves.

We shot film of the two reporters opening up to each other as they drove around Washington. Woodward related how, as a boy, he discovered that his remarried mother had spent more money on his stepbrother’s Christmas gift than his own — his first investigative job. Those moments never made it the screen. Then, at Hoffman’s insistence, a scene where his girlfriend complained that he was ignoring her; that was the only day cameraman Gordon Willis called in sick. He knew it didn’t belong. There were no anguished loved ones, no wives, children, girlfriends, or worried parents. Just our reporters on the job. Even the villains were absent — just names traded back and forth, and the very occasional TV face. The story had a focus and a purity of purpose that was almost monastic.

Goldman had a fine sense of the story’s critical beats and how to weave them together to create rising tension. This was a particularly difficult problem since the bits were disconnected and only came together after the fact. But his great contribution I believe was in knowing when to end the movie. We all knew where it began. Frank Wills spots the tape. But where does the story stop — the real-life resolution, Nixon’s resignation, doesn’t involve our journalists. I pushed to end the film with a sequence that wasn’t even in the script, when the reporters push the limits of the legal, and approach one of Judge Sirica’s grand jurors. They’re reported to the judge, who calls together all the journalists and tells them that suborning the grand jury is criminal contempt of court. He doesn’t single out Woodward and Bernstein, but he might have, with disastrous consequences. Then the other journalists try to suss out who did it and grill Woodward and Bernstein, and our boys answer with half-truths and evasions, the “non-denial denials” that their own quarries used. Now they know what it feels like to be on the receiving end. A nice irony that told a larger truth: relentless journalist and relentless politician are basically the same animal.

A spectacularly bad idea. This was America’s myth, these were our heroes, the story was all about the very difference that my ending would deny. They share the same instincts but not the same moral universe. Goldman smartly ended when it looked like our duo was at their nadir. Having misunderstood what a source was telling him, Bernstein has determined that H. R. Haldeman, Nixon’s right hand at the White House, has been implicated to the grand jury. He has not. Having printed this erroneous information, Woodward and Bernstein empowered their enemies and threatened the survival of their own paper. But it was an honest error. Bradlee pushes back:

You guys are probably pretty tired, right? Well you should be. Go home, get a nice hot bath, rest up 15 minutes, the get your asses back in gear. We’re under a lot of pressure, and you put us there. Nothing’s riding on this except the first amendment of the Constitution, freedom of the press and maybe the future of the country. Not that any of that matters. But if you guys fuck up again I’m going to get mad.

And slow move in on the boys banging out the story while Nixon is sworn in as President.

We debated the tag, the final image the audience sees before the lights come on. We had a version where a spectral Nixon waved from the helicopter window as he lifted off the White House lawn and vanished behind the Washington monument. Our editor Bob Wolfe, a sincere Republican, hated it. He called it “the boot in the face shot.” We prepared it for testing but ran the first screening without it, and he was right. We’d underestimated the emotional impact of our carefully calibrated restraint. In the context of the movie, it felt like gloating.

So we ended with the teletype reading: NIXON RESIGNS. GERALD FORD TO BECOME 38TH PRESIDENT AT NOON TODAY.

Gordon Willis had shot Klute and The Parallax View for Pakula, and had just finished the second Godfather movie. The look of The Godfather was a revelation: a moody, luminous glow that challenged the grainy grayed-out New Wave pictures and reinvented the mythic imagery of Hollywood. The producer in Pakula trusted Willis not only with the quality of the image but the visual structure of the picture. Pakula would talk at length in a general sense about the feelings he was trying to convey; Willis made the feelings tactile. When Pakula staged a scene he’d know he wanted close-ups, say, and then Willis would place the camera. Willis was the one who truly saw the story in his head. He knew precisely how each image would interlock with the others to build his story. He never zoomed his lens because he felt that changing focal length shifted perspective in a way that destroyed the picture space. When Gordon panned or tilted, the movement had to be so naturally part of the story it was invisible. By limiting his vocabulary, he intensified the meaning of the images. Hemingway said that words were icebergs, only one eighth above water. Willis’s images were icebergs.

He had to find tension in telephones and typewriters. He did it by holding back. While most talky pictures favor scenes where the camera moves along with the actors as they converse, Willis did the opposite. In the newsroom, he doesn’t move the camera until 20 minutes into the picture, at the climax of the scene where Woodward and Bernstein team up: Angry, Woodward watches Bernstein rewrite his copy, and when he finally marches in on Bernstein the camera finally moves along with him. The camera goes stationery again, until the appearance of Ben Bradlee. We first see him through Redford’s eyes as a tiny figure in his glass office. Then we jump closer as he steps out, and stride with him through the newsroom until he swings into close-up and corrals the boys. In the entire film, I count only four tracking shots in the newsroom, all at critical moments in the story, culminating at the climax of the movie in the longest, quickest tracking shot of all. In an office at the far end of the newsroom Bernstein gets his crucial final source to confirm, and the camera follows him as he half-jogs the length of the room picking up Woodward along the way to corner Bradlee entering the elevator. A straight-line move.

Here, small and shown out of context, it has no particular emotional weight. But big, after 90 minutes living in a static newsroom, it burns in the brain.

To keep the newsroom alive and always a part of the story, Willis introduced a new lens, or rather a sliver of a lens called a split diopter, that held a slice of background sharp while our reporter talked in focus up front. He and Pakula let the phone calls play out in real time with a minimum of cuts. Their masterpiece shot has Redford at his desk trying to track down a name on a check in the Watergate burglar’s account — for a full six minutes. In the background the newsroom watches Tom Eagleton resign as McGovern’s running mate. The scene begins in medium; Redford at his desk while the folks in the background huddle around a TV. The camera slowly, imperceptibly moves in (while a camera assistant eases out the split diopter) until four minutes later we are tight on Redford at the moment when he learns that the money used to fund the burglars came from the Committee to Re-Elect the President. This one shot took the better part of the day to set up.

Most movie shots are measured in seconds. Here Redford had to play six unbroken minutes of note-taking and phone calls to strangers so that we’re caught in the escalating drama. But he had the actor’s gift. He could make us believe. He cared so we cared. Without time jumps or shifts in angle we experience the real rhythms of the story and trust them, and give ourselves up to Redford’s charisma.

After more hours of struggles and mishaps, we finally had a good take. Redford and Pakula were pleased. They’d done it. The moment, which might have felt stagy, plodding, or contrived, worked. Redford was an actor who didn’t like reshooting. Pakula huddled with him. Redford tried once more. Knowing he had it already loosened him up. His new ease oiled the tension and the scene snapped. It’s his triumph in the picture. Here’s a clip from the beginning of the move:

Pakula wanted to contrast shadowy Washington with the unforgiving glare of the newsroom. So our Post, in which the bulk of the movie was shot, was lit with the harsh fluorescent lights of the real thing. This was a dangerous choice; pictures weren’t lit that way. The light is flat and general. Office fluorescents are blind to certain colors and they flicker. Willis found a full color-spectrum fluorescent for the overheads, and made banks of smaller tubes he could bring in for strategic enhancement. The room looked vibrant and unforgiving, just what Pakula wanted. But fluorescent wasn’t bright enough for the daylight scenes we see outside the windows. Willis had to have a greenish gel made to coat the windows so he could use incandescent lights on the window transparencies.

First try, the windows glowed pink, which took us to several days to solve. There’s still one distant pink window in the picture. The fluorescents also created a problem for Jim Webb, the sound man. Each overhead fixture came complete with its small, buzzing transformers. So George Jenkins placed all the transformers outside the set, and ran a separate wire from each one to its overhead tube. Miles of copper wiring, no buzz.

Redford and Pakula had the power and commitment to spend big money on small things. I was told that the most expensive shot in the movie was the one in which Woodward changes taxis on his way to meet Deep Throat. Pakula wanted us to feel the reporter being dwarfed by imperial Washington on his dangerous quest, so he had Woodward change cabs in front of the soaring fountains at the Kennedy Center. A single shot: A cab pulls up, scruffy Bob steps out and loses himself in a couple of thousand Washingtonians in black tie and evening gowns spilling onto the street before he slips into another. We recruited the dress extras on the radio. Staging took all night. Willis had tank trucks wet down the street for glistening reflections, a noir touch that gave lustrous depth to the scene. Unfortunately the trucks tanked up at the fountain, and when rehearsals were done and the time finally came for shooting, the depleted fountains shut themselves down. The sky was lightening. But the grips found a way to turn the fountains back on in time for a single take. Note the split diopter shot that leads in.

If typewriters are weapons, words are bullets. Goldman’s script opens with a close-up of typewriter keys pounding out the date. Pakula wanted us to feel the power in every letter. I’d worked with Charles Eames, the designer who made an art of looking closely at very small things with a movie camera, and he let me borrow his equipment and shoot in his studio with my cameraman friend Eric Saarinen. Eames had special lenses and extreme extension tubes. The paper became a matted field of fibers, the letter a black valley.

Extension tubes suck up light. Most f-stops are in the single digits; ours was in the hundreds. So, to film the letters being pounded out on paper, we focused projector lamps down to a point. Their beams were so hot they burned holes in the paper. We filmed the striking keys at different frame rates to capture the movement of different parts of the action, shifting focus from paper to key. When I handed Bob Wolfe this jumble of film, he was taken aback. But we stitched it together a few frames at a time. The date you see is made from 50 bits of film.

Pakula opened the picture with 18 seconds of silence and blank white blur. He jiggered the length to make it as long, as creepily unsettling, as he could get away with. Who starts a picture with nothing? Is the projector even working? Squirming in the seats. Then the jarring jolt of the first typewriter blow. For each letter, the effects editor laid in sound of a cannon blast, scraping off the boomy tail and overlapping instead the tail half of a whip crack. A cannon that cut like a bullwhip. We were working on magnetic film so this sound editing was done with razor blades. We overlaid this with just the right typewriter sound (we had six to choose from). In the pre-digital era, this was recorded from sprocketed magnetic film on reels that had to be rewound all together, then recorded onto tape at sound speed. Redford was particularly involved, poring over the effect again and again until balance and reverb was just right, solid and threatening, apocalyptic but real. Three hours on the mixing stage.

Here they might seem small, blurry, and muffled — here they’re just letters, but imagine this 20 feet tall, crisp, and multiphonic.

Editing is a mysterious process, a matter of rhythms and associations. What silent film pioneer Lev Kuleshov called “the juxtaposition of uninflected images.” The brain makes connections between successive shots, trying to create a narrative, wanting to feel an emotional logic. We feel movies so strongly because we think we’ve made them up ourselves. But in the hands of a skillful editor, viewers feel precisely what the filmmaker wants them to. It’s the essence of moviemaking: Managing those psychological connections is the one new art that film brought into the world. But the difference between a captivating film and a tedious slog can be practically invisible.

While we were shooting, Bob Wolfe assembled the picture. Pakula had noted his preferred takes and Wolfe put it together as best he could using Karen Wookey’s notes as a guide. Pakula was pleased with the dailies and the movie they were building in his head. Good performances, good work by Willis. But you never know until you see it all together on a screen. He expected it would be cumbersome, as Wolfe was committed to using everything in the script. But Pakula was confident he’d be able to pare it down.

When he finally saw the assembly, Pakula came away deeply discouraged. His worst fears were realized. He’d shot a dull, complicated, inert tale of journalistic handwringing and offscreen shenanigans. Hard to follow and harder to care about. Maybe the smart money had been right all along.

Then Pakula looked at it again, a reel at a time, on the screen of the Steenbeck flatbed. I was with him. Bob Wolfe was a fine editor who’d worked for Sam Peckinpah on a few films, including The Getaway. He was cutting as Peckinpah had trained him. Peckinpah liked to give his films energy and pace by weaving short cuts together, using overlapping dialogue to carry us from one shot to the next. He called it “greasing the cuts.” Wolfe had done that here. But Pakula wanted precisely the opposite. He wanted you to feel the cut: “If I’d wanted them in the same shot, I’d have put them in the same shot.” Pakula was counting on the tension and the distance created by the cut, so that when Bernstein asks the bookkeeper a question, for instance, we hang on the moment and hope along with him.

Pakula told his editor to play the uncertainty. Wolfe went through and added frames back at the head and tail of shots, restored the pauses that Pakula had witnessed on set, and the scenes came alive. Tension pulled you through the story. It was longer, but it felt shorter. Gordon Willis was responsible for the look of the picture and its visual architecture, but Pakula shaped your feelings in the editing room.

Pakula said that editing was his favorite part of making movies. He liked the luxury of trying things over and over, impossible on set, finding incremental changes that built a moment or charged a performance. It was slow work — checking alternate takes, varying rhythms, dropping lines, shifting from one actor’s point of view to another’s. As Oscar Wilde put it, he “spent most of the day putting in a comma and the rest of the day taking it out.” But it worked for Wilde, and it worked for Pakula. The film kept getting better.

Pakula kept me around. My analytic nature appealed to him. Splicing the separate film and track, adding tiny bits, and moving things about was time-consuming labor. With deadlines looming, we took on a second editor, Lou Lombardo, also a Peckinpah graduate. Pakula went back and forth between them, and I was at his side for almost all of it. I saw the performances sharpen, I felt the rhythms unlock the emotions in the scenes. It was the movie education of a lifetime. (I did it well enough that when Pakula directed a movie I wrote he shared his editing room with me again.)

In time, the film revealed its theme to us — what John Huston called “the bell that rings in every scene.” This wasn’t just a movie about the reporters’ need to know. It was their sources who had the most at stake, and the emotional heart of the interrogations was their internal struggle. Why confess? Why tell the truth? They had nothing to gain. Sensible folks on both sides, reporter and source, wouldn’t risk themselves the way our characters do. Their drives are beyond logic and intertwined, two sides of the same urge really, locked in an intimate tango. They can’t be explained any more than a tango can be explained, but they’re certainly felt, and that ineffable essence drives the scenes — if this story could be explained in words you wouldn’t have to watch it play out. This is the real power of the picture. This is why it recruited a generation of investigative reporters.

Bookkeeper opens up to Bernstein

We toiled for three months. Redford, off on other projects, had the sense and the trust to let Pakula do his job, and dropped in now and then to provide fresh eyes. Coblenz was assembling the promo reel for the National Association of Theater Owners. These were the folks who would book the movie. The gatekeepers. Also the first civilians to see footage. Their reaction would define expectations for the picture, and we knew there was a lot of doubt out there. Would this be another overhyped dud like The Great Gatsby? Would theaters owners even want the picture?

A week before the NATO convention, Coblenz ran his reel for Pakula and Redford. I was not invited. They exited lock-jawed. Worried that the story would be static and plodding, trying for trendy dynamism, Coblenz had cut together a frantic collage of the heroes running hither and thither waving telephones and sheets of foolscap. He’d proved that the picture was everything he was afraid it would be. Redford and Pakula were in a bind. Not showing this reel was a big risk. It implied we had something to hide. It would hurt bookings and spark gossip, but Redford thought that showing this was worse, and Pakula agreed.

I’d lived with the movie, I knew every foot, and I knew what drove the picture. I asked Pakula to give me the weekend with assistant editor Tim O’Meara. We put together a few critical moments in the picture. We began with Frank Wills spotting the telltale tape and built to the moment in the dead of night when Woodward and Bernstein get the honest, upright treasurer of the Committee to Re-Elect the President to admit without actually saying it that Nixon’s top man H. R. Haldeman was behind the dirty tricks. A handful of scenes that showcased the tension of the chase: The reporters need to know and the dance of the confessional urge. I ran it for Pakula. He ran it for Redford.

I’d avoided Redford. That was a relationship that Pakula kept strictly to the two of them. I was Alan’s man. Redford didn’t know what I did, only that I lurked around his newsroom set far too much during shooting, trying to avoid his eye line. This was our first real connection. He liked what he saw — I understood his movie, and I’d condensed it into something that promised possibilities. Apparently all that skulking about had not been in vain. Mostly, he was relieved. He shipped the reel. That single weekend I earned out for the entire picture. Redford asked to see my Exploratorium. I ran it for him. It was shot in 35 millimeter, half Eamesian montage half vérité documentary. He said kind things. When we wrapped, I sold him a mountain-climber project for me to produce at Columbia.

As Bill Goldman said, “Nobody knows anything. Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what's going to work.” As I recall we only previewed All the President’s Men once, out of state. The audience didn’t know what it was getting. The title was met with silence and scattered boos. The silence held. A few people walked out muttering about a smear job. More silence. I was struck with how abstract the story was. The enemies were just names, their crime was writing checks. Our boys had nothing personal at stake. I leaned in to Pakula. “This is an intellectual picture,” I said. “I know,” he said. “Don’t tell anybody.” And then the picture had its first light moment and the whole room laughed. Silence had meant immersion. So we had them.

After the movie wrapped, we went our separate ways. During the editing, Exploratorium had been nominated for an Oscar and I’d become an Academy member, part of Academy President Gregory Peck’s youth movement. When All the President’s Men was nominated for eight Oscars, I put in for tickets to the award ceremony. Since Redford had made me Associate Producer in the end, the AMPAS lady seated me and my wife with the All the President’s Men contingent, fourth row center, three seats down from Alan Pakula. He was up for Best Director. I leaned over to wish him luck. He was startled: “What are you doing here?”

John Avildsen won. Rocky.

For another read about the making of the film, check out out the Washingtonian piece here.

¤

LARB Contributor

Jon Boorstin is a writer and filmmaker who works in a broad range of media. His novel The Newsboy's Lodging House won the New York City Book Award for historical fiction. He made the Oscar®-nominated documentary Exploratorium; wrote the IMAX film To the Limit, winner of the Geode Award for best IMAX film; and wrote and, with director Alan J. Pakula, produced the thriller Dream Lover, winner of the Grand Prix at the Festival du Cinéma Fantastique in Avoriaz, France. He is the co-creator of the television series Three Moons over Milford, a comedy about the end of the world. Boorstin has written a book on film theory titled Making Movies Work and has taught film at USC, the American Film Institute, the Hamburger Filmwerkstatt, and as a Fulbright professor at the National Film Institute in Pune, India. Boorstin’s new novel Mabel and Me was published in April.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A “Just and Liberal” Vision of War

Grandin wants us to think about "the outsized role" Kissinger "had in creating the world we live in today, which accepts endless war as a matter of...

Shoe Leather: On “Spotlight”

For writer-director McCarthy and his co-writer Singer, "Spotlight" is a leap in terms of scale and depth.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!