“Of Course, of Course”: On Anthony Veasna So’s “Afterparties”

Summer Kim Lee reviews Anthony Veasna So’s “Afterparties.”

By Summer Kim LeeAugust 30, 2021

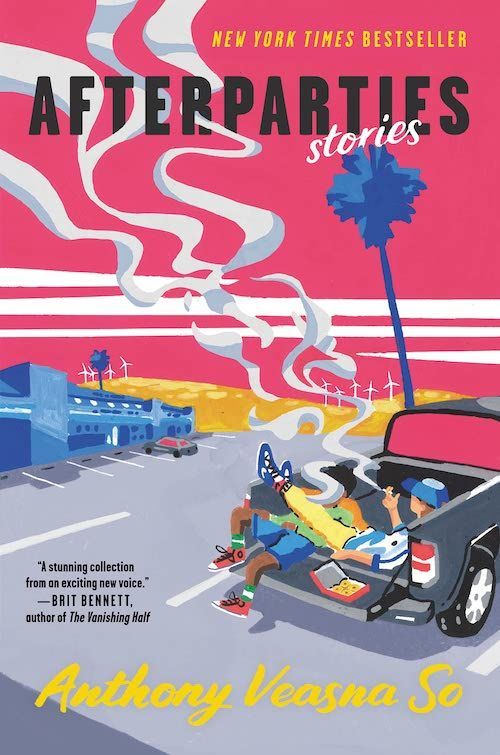

Afterparties by Anthony Veasna So. Ecco. 272 pages.

IN HIS ESSAY “Duplex,” Anthony Veasna So wrote about the work he created while he was an art student in the Bay Area. He had tried computer science, but after failing courses, he switched his major and started developing his own artistic practice — a combination of photography, painting, printmaking, and collage. At the same time that he was attending lectures on Renaissance paintings, he was also helping his parents maintain duplexes in Stockton that his father rented out to other Cambodian families. On weekends, So would drive to the Central Valley to fumigate empty rooms, deep clean carpets, re-tile floors, and paint walls varying shades of beige. He learned about the work of artists from the Western canon, like Jackson Pollock and Diane Arbus, as much as he learned about the work of his father, the owner of duplexes and a car-repair shop, and a refugee and survivor of the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime. From the canon, So learned about egg tempera and sfumato; from his father, So learned “the methods, the tricks, the art of renovation.”

In his posthumously published collection, Afterparties, So took up the “art of renovation.” Like the duplexes he and his parents prepared again and again for tenants that come and go, and like his artworks that layered tiles of family photographs with photographs of the killing fields, his writing did the repetitious work of repair, preservation, and renewal. Afterparties is populated by recurring characters — mainly young adults — who the reader meets and re-encounters throughout the collection. As a result, the stories offer a nonlinear series of loops and returns in which reincarnation is both literal and figurative.

Ves, the queer narrator of “Maly, Maly, Maly,” spends an afternoon with his straight cousin Maly before attending a party celebrating the reincarnation of Maly’s mother, Somaly, reborn as Serey, a second cousin’s baby. With Ves set to move to Los Angeles in a few days for college, the party marks Serey’s arrival, Somaly’s return, Ves’s departure, but also Maly’s stasis, as the one staying put. All four characters — Somaly included — reappear in another story, “Somaly Serey, Serey Somaly,” where Serey, now in her 20s, is a nurse tasked with caring for her grandmother’s second cousin in an assisted living home. The conjoined, overlapping names of story titles become incantations that preserve and hold in time the reincarnated lives each story holds.

In “Maly, Maly, Maly,” Ves already anticipates needing to remember certain things about being home, specifically his close yet fraught relationship with Maly, whose beauty, confidence, and self-absorption as a woman have shaped what Ves describes as his “very cliché” “gay sob story,” wherein he plays the role of the odd, overlooked sidekick. When they were younger and had sleep-overs, “I was always there for Maly,” Ves explains, “right where she wanted me, on the floor beside her bed, doling out reassurances until she sank into her dreams.” Ves’s descriptions of Maly convey his admiration for her with a tinge of resentment, as well as guilt for leaving. Throughout, he mentions how they needed each other to make it to adulthood, or whatever that was — “a revelation until it’s forgotten as life is lived.” As the party for Maly’s mom and their third cousin is about to begin, Ves feels himself drifting from the scene before him: “For a moment, I believe I am the only person in the neighborhood separate from the celebration. […] Staying here, in Maly’s wake, I understand how truly alone I am.” With the realization that he is soon moving away, Ves finds himself feeling like the one who is, in fact, staying behind — “staying here, in Maly’s wake.” In no longer being found where someone else wants you, but instead alone on your own, Ves’s “gay sob story” is shaped by a feeling of alienation from one’s home, a suspension between being “in” and “out,” which, as David Eng writes, is a feeling familiar to queers and those of the Asian diaspora alike. Although the party has not yet begun, Ves is already thinking about what comes after — on the life to come — imagining what it will be like to return to Stockton, finding Maly and those he loves changed in ways that he has missed and that leave him longing for what was. Perhaps this is what marks the time and place of the afterparty: not so much a continuation or iteration of another party, but a preparation for an ending one is not ready for, not yet. The repetition of renovation, then, is about a multiplicity of afters, of making something feel almost like new, like another beginning.

¤

“The short-story form can only accommodate a very specific content: basically, absence,” observes Elif Batuman. “Missing persons, missed opportunities, very brief encounters, occuring in the margins of ‘Life Itself.’” For So, “Life Itself” might happen in Los Angeles, New York, or the Bay Area, however this “Life Itself” was not what So was interested in capturing. His short stories live in what is missed and missing elsewhere — in Stockton, California, where the city’s inhabitants might be perceived as stuck, affectively detached from their own story even when it is about them. In “Superking Son Scores Again,” a teenager relays the story of Superking Son, a former high school badminton star, who runs a grocery store and relives his glory days as a high school coach. A college graduate, who narrates “The Shop,” moves back home to Stockton and works at his father’s struggling car repair shop, all the while wondering what his life would be like if he stayed. In “The Monks,” Rithy (Maly’s on-and-off boyfriend) has a brief stay at a Buddhist temple to mourn the death of his father, unsure of how he should spend his time, whether alone or with the monks around him. So does not idealize his characters — they struggle with finding jobs, running businesses, debt, divorce, depression, and substance abuse. Yet, he places them with great care in social worlds that are far from impoverished, worlds where momentary renewal is found in what Life’s linear narratives of set departures and arrivals might dismiss as failure. So’s characters inhabit what Lauren Berlant called the “temporary housing” of the “impasse,” where the feeling of arrested development necessitates the quick fix or makeshift repair, which are not shortcuts so much as they are a resourceful part of, as Berlant described it, “how best to live on, considering.”

Afterparties’s short stories generate their own loops, as if they are circling back and around the streets of Stockton. To circle the same block can seem shady, or it can also be a hopeful expression of longing, of wanting to get caught, drawn in, and carried by the gravitational pull of a familiar place. When reading these stories, one can feel the pull of Stockton through a map not available anywhere else. There’s a park next to a closed middle school, parking lots of hollowed-out malls, a 24-hour donut shop on a street with a broken streetlamp, strip malls with video stores, massage parlors, and nail salons, the back storeroom of a grocery store, and badly lit badminton courts at an open gym. These are post-recession landmarks and remnants of a formerly bankrupt city that never managed to fully recover — what Ves dryly calls “the asshole of California.” But it is also home to Cambodians who arrived once they were relocated from refugee camps and granted US citizenship in the 1980s. Stockton is a site of abandonment and neglect, reflective of how the US views refugees, immigrants, and the poor. Yet, through the angst, boredom, and restlessness of young characters, such spaces are preserved and given another life — anything but “Life Itself” — made for teen loitering, smoking a joint in a car, eating donuts and tacos, selling home-cooked Cambodian food, burning bootleg DVDs of Thai soap operas dubbed in Khmer, house parties, and other antics that make a living and pass the time. What might otherwise be a forgettable, forgotten city within the United States’s narrative of its own benevolence is given, in So’s prose, a memory of its own.

While Afterparties is grounded in its sense of place, So approached the short story as a minor form that unseats any singular understanding of Cambodian American life. For So, the short story form reflects the impossibility of representing the entirety of a community and what it has been subjected to. His work offers recursive glimmers of lives irreducible to anything like the set demographic of a “minority” group. He playfully and incisively pushes identity and the burden of representation to the very limits of its prescriptive, essentialist logics. He risks having an earnest reader take his work too seriously when, for instance, the narrator of “The Shop” declares that all Cambodian men do is fix cars, sell donuts, and go on welfare, at the same time that he dares that same reader to overlook the history and structural inequalities that undergird and enable such a stereotypical claim. For So, pain becomes a punchline, rather than a means of claiming a recognizable minoritarian identity. So sought out the brutal, heartbreakingly funny qualities of melancholia, where the refusal to let go of what one has lost, of trauma either lived or inherited, is also a refusal to let a good joke go unnoticed. The repetition of trauma, the return to Stockton, and the reincarnation of mothers and second cousins are a commitment to the bit, a means of dragging the joke out until a reader has no choice but to laugh.

¤

So’s sense of humor is inseparable from his own awareness of how he is positioned as a queer Cambodian American writer, both within and in relation to the genre of Asian American literature. Asian American literature, in its established, institutionalized legibility, can at times feel stultifying in its exceptionalization of injury and harm as the primary means through which an Asian American writer can claim a coherent, recognizable identity. It is not that So denied how trauma shapes the lives of Cambodian Americans — the devastation of genocide looms large for his characters whether they lived through it or not. Rather, memories of fear, devastation, loss, and violence render incoherent any identitarian claim. Memories of another life in another time and place are not in service to a singular, holistic, linear, or historical narrative of the Asian diaspora writ large, but rather in service to the kinds of piecemeal, ad hoc repairs So and his father knew how to do so well.

In “Three Women of Chuck’s Donuts,” a mother named Sothy, and her two daughters, Tevy and Kayley, work at a 24-hour donut shop, where a silent, mysterious man starts to frequent the shop late at night, only to buy an apple fritter and leave it untouched as he sits at a booth looking out the storefront windows. The two daughters cannot help but be curious: Who is he? Why is he there? More importantly, is he Khmer? Sothy is sure of it, just from a glance, but when her daughters ask how she knows, she merely replies, with a second final glance, “Of course he is Khmer.” Tevy and Kayley decide they have to investigate further, for “that of course compelled Tevy to raise her head from her book. Of course, her mother’s condescending voice echoed, the words ping-ponging through Tevy’s head, as she stared at the man. Of course, of course.”

The condescension of the repeated phrase, “Of course, of course,” as an unfinished, unverifiable thought, inspires Tevy to write a paper for her philosophy class at a nearby community college tentatively titled, “On Whether Being Khmer Means You Understand Khmer People.” This relation between being and knowing is Tevy’s main focus — “What does it mean to be Khmer, anyway?” she asks — as someone who feels detached from her own Khmer-ness:

Being Khmer, as far as Tevy can tell, can’t be reduced to the brown skin, black hair, and prominent cheekbones that she shares with her mother and sister. Khmer-ness can manifest as anything, from the color of your cuticles to the particular way your butt goes numb when you sit in a chair too long, and even so, Tevy has recognized nothing she has ever done as being notably Khmer.

The man coming into the shop promises to offer concrete evidence of Khmerness beyond a numb butt. As a stranger, an unknown Cambodian, he presents an objective point of view. When they finally speak to him, though, there is no easy recognition of a shared Khmer-ness, no unifying sense of being that originates from a shared, traumatic past. Tevy and Kayley discover that what they thought they did not yet understand about being Khmer was something they already felt and carried. Maybe being Khmer does not have to mean anything in particular — not in a nihilistic way, but in a way that relieves them of the burdens of having to be knowably Khmer.

¤

So died in December 2020, leaving behind a body of work that shifts the melancholic structures of feeling that have long been a crucial part of Asian American literature. In reading Afterparties, it is clear how ways of writing out the melancholic have started to feel too safe, foreclosing the social worlds that Asian American literature can build, affectively charged by the risk of laughing through heartache, homesickness, and loss. He brought our attention to these worlds, and to the specific world of Stockton, California.

I share with So a certain wary cynicism around the success and demand for more Asian American representation. In his review of Crazy Rich Asians, So observed that “[i]f Crazy Rich Asians proved to be a hit, studio heads and publishing hotshots would buy up Asian American stories the way my aunt buys dollar flip-flops during Old Navy’s annual flip-flop sale — in a delirious, short-lived mania. If it failed, we’d have to start studying for the LSATs.” If one cannot make it big by manufacturing and selling the cheap products that the market demands, one resorts instead to model minority pursuits. The predicament is bleak, but So’s hyperbole was not a rejection of visibility so much as a much-needed critique of the very absurdity of its high stakes in the public imagination. In So’s absence, we would do well to read his work and the work of other Asian American writers as that which finds pleasure and humor in being at least a little irreverent toward the conventions of Asian American literature and, from there, to see how others might write — and read — differently. So’s collection feels like an opportunity to reapproach the genre, where humor drives repeated attempts at expressing the moment of transition and in-between, where renovation is required, as the act of making a space fit for living, over and over again, when and as needed.

By the end of Afterparties, I find myself returning to “The Shop,” where the narrator keeps stumbling across “dumb epiphanies about home.” So writes with a particular way of listening. As he wrote in his essay “Baby Yeah,” he prefers to listen to songs, like those by the Stockton indie rock band Pavement, on loop. It speaks to a certain obsessive close attention and attachment to what you know so well. In “The Shop,” the narrator drives his family’s old Honda Accord, listening to Khmer music played from a burnt CD that has been stuck in the stereo for as long as he can remember:

I barely understood the lyrics, aside from a few phrases in the choruses, but I knew the melodies, the voices, the weird mix of mournful, psychedelic tones. When I tried articulating my feelings about home, my mind inevitably returned to these songs, the way the incomprehensible intertwined with what made me feel so comfortable. I’d lived with misunderstanding for so long, I’d stopped even viewing it as bad. It was just there, embedded in everything I loved.

This is what comes through in So’s writing: a love for a home to return to, held in songs that you do not and cannot sing along to but which you have nevertheless been hearing your whole life; a comfort taken for granted because it has always been there, a presence felt even from afar or at a low volume, always in the background. The nosey force of the music is an involuntary, nagging pull backward that might be perceived as regression, but actually is something more stubbornly aimless in the present. It is a near refusal of nostalgia because the loop of the familiar yet misunderstood assures that the song never ends, never recedes too far into one’s memory and instead stays literally stuck. And is that not “dumb” to realize? Dumb — not because it is wrong or ill-conceived, but because it so “incomprehensible” and yet feels so inexplicably obvious. “Of course, of course.”

¤

Summer Kim Lee is an assistant professor of English at UCLA.

LARB Contributor

Summer Kim Lee is an assistant professor of English at UCLA.

LARB Staff Recommendations

My “Minari”: On Asian American Immigrant Cinema

Hannah Amaris Roh explores how the film “Minari” provides a generative and moving departure from the typical Asian American immigrant film.

“Why Are You Pissed!”: On Cathy Park Hong’s “Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning”

Cassie Packard considers “Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning” by Cathy Park Hong.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!