No Monuments: On Ian Penman’s “Fassbinder Thousands of Mirrors”

Chris Molnar reviews Ian Penman’s “Fassbinder Thousands of Mirrors.”

By Chris MolnarMay 2, 2023

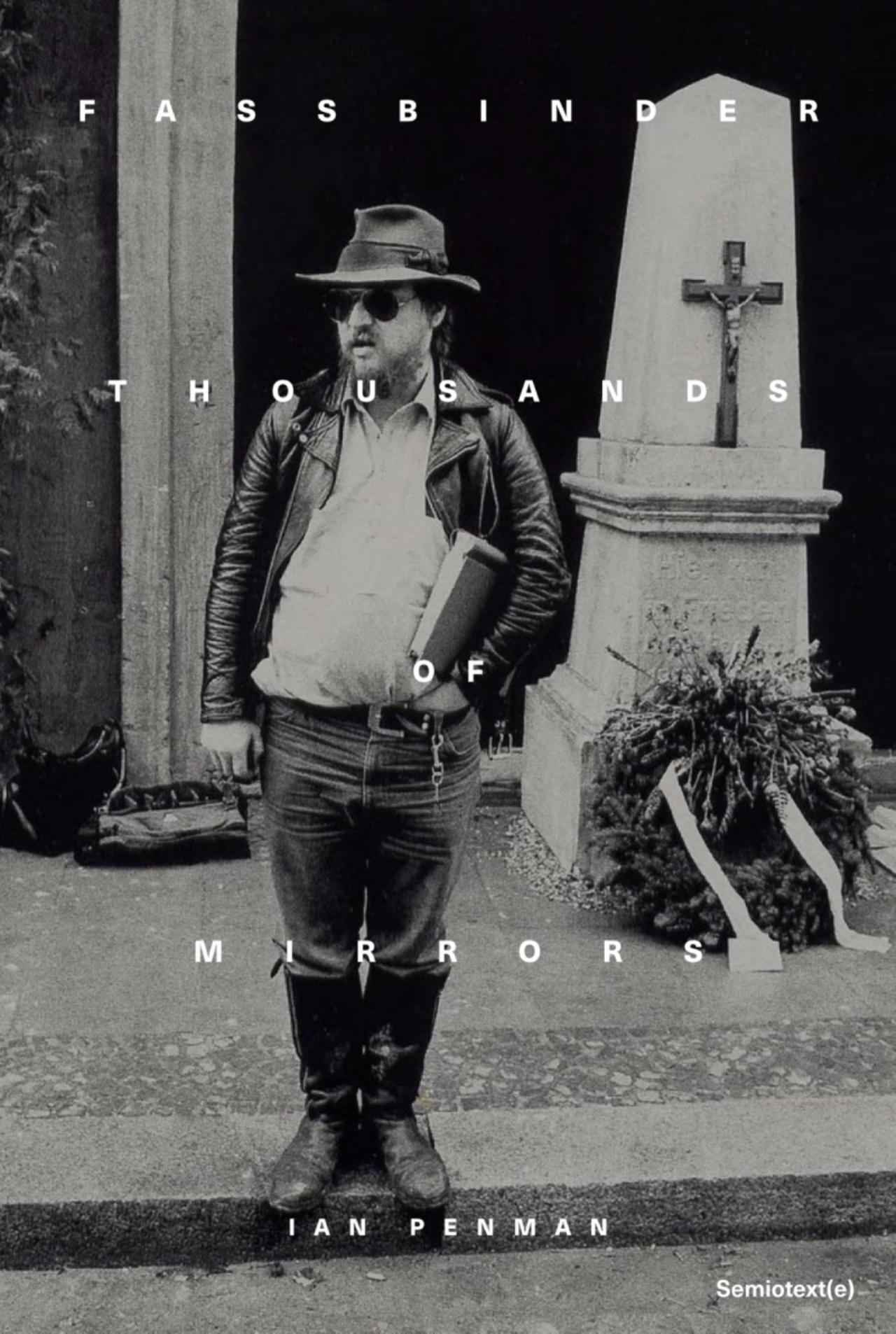

Fassbinder Thousands of Mirrors by Ian Penman. Semiotext(e). 200 pages.

“WHY EXACTLY is it thank Christ he has escaped being turned into a monument?” critic Ian Penman asks near the beginning of his first original book, Fassbinder Thousands of Mirrors (2023), a curious and, given the dearth of literature, essential companion to the films of Rainer Werner Fassbinder. As Penman writes, contemplating his subject’s early death in 1982, “Four decades on the messiness remains; he hasn’t become a smoothed-out icon or convenient role model; something in him still resists such easy appropriation. Too untidy and paradoxical. Difficult to canonize, difficult to mourn. Difficult to assimilate.”

Short and structured as a mélange of biographical and autobiographical fragments—like a more conversational Nietzsche in The Case of Wagner (1888), or lengthier cousin to Wayne Koestenbaum’s “Five Fassbinder Scenes” (2005)—Thousands of Mirrors is the culmination of Penman’s ecstatic interrogative style, grown from 45 years at outlets like NME, The Wire, The Face, and, most recently, City Journal and the London Review of Books.

If that style is feeling and research blended into critical arguments and studded with personal truth, Fassbinder’s style is feeling itself condensed and narrativized into truths still uncomfortable to watch. Among the New German directors who emerged in the 1970s, the elemental odyssey of Werner Herzog or melancholy romance of Wim Wenders remain the easiest introductions. Everything about Fassbinder is outsized and unruly, a universe unto itself, difficult to grasp even after watching one of his relatively conventional, universally lauded films like Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974) or The Marriage of Maria Braun (1978).

Faced with a filmmaker who was constantly productive and legendarily decadent to the point where the stories of vast appetites and chemical, sexual, and emotional extremes fill a biography—see Robert Katz’s lurid yet (contrary to received opinion) non-scurrilous Love Is Colder than Death: The Life and Times of Rainer Werner Fassbinder (1986)—even the most sober-minded critics are practically forced to write transgressive literature in any sympathetic overview, relating parables of mental cruelty, transcendent genius, and briefcases of cocaine.

In the 13 years preceding his death at the age of 37, Fassbinder produced 43 films, including television movies and miniseries. This is physically difficult: difficult to secure financing for, and to maintain the energy for—even for filmmakers who do not write or star in their own films, as Fassbinder often did. It is unparalleled for someone working at the highest levels; there is no point at which he is working on autopilot, or making anything unconsidered. The world of these films is instantly distinctive, with an off-kilter energy and quick yet deeply considered directorial decisions. They look intensely and unsentimentally at human relationships, occasionally striking a hopeful note yet unsparing to their core.

This is all informed, activated by his personal life; his actors and crew, beginning with his Munich Anti-Theater, were also family, lovers, or otherwise acolytes, continuously employed for years—or until a blow-up, which were not infrequent. Harry Baer and Kurt Raab began as stars (acting styles iconically lethargic and pissy, respectively) before shifting to production; Fassbinder’s nonactor mother Lilo, chanteuse ex-wife Ingrid Caven, and long-suffering factotum Irm Hermann became iconic supporting actresses, along with lovers Günther Kaufmann, El Hedi ben Salem, and Armin Meier, whose relationships with him were possibly more fraught and dependent than any others. Contradictions and complications abounded. Fassbinder was openly gay, but his films on the subject tended to focus on class and power. His anti-capitalist terrorists of The Third Generation (1979) are funded by businessmen; his victims are in control (1971’s The Merchant of Four Seasons); his abusers are victimized (1980’s Berlin Alexanderplatz); the ludicrous gay caricatures of Querelle (1982) angrily insist on their straightness and, in so doing, become more real and gayer. Meanwhile, the trans hero of In a Year of 13 Moons (1978) is not even psychologically trans, cis, gay, or straight—just a frighteningly pure scream from the human heart. Penman: “It is not some ideal other he seeks, but his own real, true, untrammelled self.”

The obvious positions on every issue Fassbinder tackles—race, gender, addiction, all relevant today—are all subverted in favor of examining raw desire and the bourgeois prisons that ensnare us. It’s what Thomas Elsaesser, in Fassbinder’s Germany: History, Identity, Subject (1996)—the only book to elide Fassbinder’s life in favor of academic analysis—calls a “problem solving machine,” transgression with the goal of finding truth beyond accepted discourse. You barely see this in popular film today; I can’t imagine what kind of determination it took in the 1970s to step so far outside of polite society as well as the dialectic that polite society forces us into, in a Germany where Nazis were not only fresh in the mind but also clockable in the streets.

¤

I can feel myself falling into the endless trap of reciting the facts, the gossip, the précis of each movie. So instead, I’ll recount what it’s like to watch all of Fassbinder’s movies in a row. They begin with pure energy, the director himself young and ruggedly beautiful, with a hypnotic screen charisma that powers inventive, low-budget short films; rough and artsy gangster flicks (his first feature, 1969’s Love Is Colder than Death quotes 1960’s Breathless and prefigures 1996’s Bottle Rocket); filmed theater; and a powerful proto-Jarmuschian comment on bigotry with the guest-worker black comedy Katzelmacher (1969). Fassbinder owns the screen whenever he appears along with constant leading lady Hanna Schygulla, a universe of complex feeling and expression unto herself. These first films, 10 in just over a year, are primordial, Brechtian, unbeholden, a thousand dead ends and foreshadowings, culminating in the hilarious, completely self-reflexive Beware of a Holy Whore (1971), which features the whole gang of familiar faces making a movie in Spain, as they had just six months earlier for Whity (1971), parodying Fassbinder’s own tantrums, the dullness, the dalliances, the inside jokes, the relentless artmaking. As Penman writes, “These are exploitation movies, and what he is exploiting is his own life.”

This only covers a glancing few of the many movies he made in his first five years. Even quickly recapping some of the films in order to describe the oeuvre isn’t easy; Penman does not attempt it. There is an inviting feel to that approach, hearing totemic titles like Gods of the Plague (1970) or Why Does Herr R. Run Amok? (1970) uttered like invocations, one that respects the reader in a way that most filmic companions do not. But for a reader who hasn’t already watched the movies, or bought his book, it seems important to try. That early era—capped off by the elemental ice-water masterpieces The Merchant of Four Seasons and The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (both 1972)—segues gradually into his high art era, after young Fassbinder’s last hurrah as Fox in Fox and His Friends (1975), as the director aggressively gains weight, finds drugs, and begins making imperfect but rivetingly strange international art films like Chinese Roulette (1976) or Despair (1978), and even stranger domestic ones like the hysterical Satan’s Brew (1976) and the devastating masterpiece In a Year of 13 Moons, before becoming famous, imperial Fassbinder: a calm, radiating force on set journeying through German history with Maria Braun, Lola (1981), Veronika Voss (1982), and others, his lenses softer, scope broader yet ultimately with the same concerns, ending abruptly, unexpectedly, but somehow appropriately with the phantasmagorical and endlessly symbolic Querelle, like a Tom of Finland version of Eraserhead (1977).

¤

Although chiefly a music critic, Penman sneaks Fassbinder into all his major work, like a secret code, a loaded reference to all the above. He reviews the Fassbinder biography Love Is Colder than Death in his first collection, Vital Signs: Music, Movies, and Other Manias (1998), quotes him on the subversiveness of Douglas Sirk’s 1950s melodramas in his long-form study of mid-period Scott Walker, “A Dandy In Aspic” (2012), and compares him to Charlie Parker in his second collection, It Gets Me Home, This Curving Track (2019). Between Signs and Curving Track, the array of artists discussed by Penman shrank drastically as the articles expanded, and the ones kept around—John Fahey, Parker, James Brown, Prince—indicate some kind of zooming in until we here reach Fassbinder alone.

In a sense, they’re a perfect match. Penman’s autodidactic knowledge of and empathy for his subjects eludes progeny like Brian Dillon who rely more on credentialed authority, and direct descendants of the blog era like cokemachineglow lack his unsinkable dedication. Fassbinder’s heirs could similarly be divided between less emotionally complex showmen like Lars von Trier and mumblecore, or the countless student filmmakers who mimic the feeling of instantaneous creation without his resilience and moral, aesthetic seriousness.

This all comes together at the beginning of the book, where Penman opens with a description of the Fassbinder film, which is in some ways an autobiographical skeleton key: the director’s autofictive opening segment to Germany in Autumn, the 1978 anthology film that commissioned leading German directors to contribute shorts about the country’s far-left militancy crisis. Obscure and unavailable on streaming, it is well worth tracking down. The film starts with an overture by Alexander Kluge showing the funeral of assassinated businessman and former SS officer Hanns Martin Schleyer, an all too familiar scene of unspoken tension between the powers that be and those who wish to overthrow them. Then, suddenly, we are in what appears to be Fassbinder’s own apartment. With deceptively lush cinematography by his longtime collaborator Michael Ballhaus (who would go on to become Martin Scorsese’s go-to director of photography), it may be the most straightforwardly beautiful work he made to that point, his idiosyncratic angles and stillness incorporated into deep shadows, a leap not unlike the one made in his mainstream breakthrough from earlier that year, The Marriage of Maria Braun.

But unlike that crowd-pleaser, Autumn gives us Fassbinder’s increasingly unruly hair, belly, and even his flaccid penis, unceremoniously visible under a white T-shirt. Only three years previous, in his final starring role in one of his own films—as the titular lottery-winning hustler Fox in Fox and his Friends—he was handsome, full of the raw magnetism that made him the best actor to star in his own films, hilarious and unpredictable, walking strictly to a beat you can never learn. Here he’s still magnetic, with the first signs of the powerfully disheveled man you see in his remaining cameos and the bonkers space disco B-movie, Kamikaze 1989 (1982), that he starred in before his death. But he is troubled, distinctly, in a way that before felt tucked under bravado. His ex-wife, Caven, calls to inform him of the apparent suicide in jail of leading Red Army Faction members. “He alternately berates and beseeches his impossibly patient partner, Armin Meier. He tears into his mother for her mildly reactionary politics,” Penman writes. “He orders a delivery of drugs, then flushes them away when he hears a passing police siren. He never stops smoking, moving, talking, thinking. It is a portrait of a man utterly sure of himself, and yet flailing.”

¤

It’s all not unlike Fassbinder Thousands of Mirrors itself, which presents the more quotidian circumstances of its creation in numbered sections tucked between short paragraphs on Fassbinder’s influences, or unmade films, or apocrypha. Using the illusion of the exposed self to engage the person, to dramatize something too vast to see fully head-on—postwar Germany for Fassbinder, Fassbinder himself for Penman. “For the longest time, not writing this book was itself a way of not coming to terms with various things,” he writes.

[S]o I gave myself a three-to-four-month time frame. Yes, I had been thinking about doing this for a long time, but that was precisely the problem: I might and probably would go on thinking about it forever, and never get anything started never mind finished, the way he always did, while alive, month on month, year on year, without fail.

Yet, by the end he hedges, contextualizing his youthful infatuation with Fassbinder as a sign of the times, the no-way-out paradoxes of Fassbinder’s characters as perhaps the projection of a “stunted boy-man, used to fetishizing his own pain, but wholly without empathy for the often far greater pain of others?” Here I disagree—the empathy I find in Fassbinder’s films is greater than that in any others. And if the artist, any true artist, remains a child, it is also to have the “taint of innocence,” as Penman calls it, to see and embody the “hope of love and its distant mirage shape” that manifest in unconditional empathy, the kind we need in our own no-way-out paradox, that of being alive in a world full of hate and pain, that leaves us open to hurt but gives us power nonetheless.

The book finishes strangely, with appendices of disconnected quotes from tangentially related thinkers and artists, petering out in a polyphony of found notecards, as if the energy Penman has built in the book has been exhausted through trying to find the yes-but in an oeuvre that defies such a thing. And so, while to a certain extent this is the efficient, gregarious guidebook that neophytes have been missing, Fassbinder still resists being turned into a monument, and all the better for it.

¤

LARB Contributor

Chris Molnar is co-founder and publisher of Archway Editions, as well as co-founder of the Writer’s Block bookshop in Las Vegas.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Spring Break Forever

On its 10th anniversary, Paul Thompson revisits Harmony Korine’s “Spring Breakers.”

Trick of the Light: On Martin McDonagh’s “The Banshees of Inisherin”

Frank Falisi writes about Martin McDonagh’s treatment of art and politics in “The Banshees of Inisherin” and his other works.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!