Spring Break Forever

On its 10th anniversary, Paul Thompson revisits Harmony Korine’s “Spring Breakers.”

By Paul ThompsonMarch 22, 2023

1. The most important film in the history of the American avant-garde is Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), a 14-minute short by an immigrant from Ukraine who, sometime after leaving New York for a house on one of those capillaries north of Sunset near the Chateau Marmont, renamed herself Maya Deren. Born Eleonora Derenkowska to a mother who adored the Italian actress Eleonora Duse and a psychiatrist father—after fleeing the pogroms, he would work at New York’s State Institution for Feeble-Minded Children, in Syracuse—Deren dabbled in journalism, clothing design, and dance before the move to Los Angeles, where she planned to focus on poetry and still photography. There are straightforwardly feminist and straightforwardly Freudian readings to be made of Meshes, but it’s more confounding than either, its figure with a mirrored face always just out of reach, its gleaming knife literal and representational at once, its logic clearer and more cryptic than any dream. Around the time she shot the film, on a budget of $275 and with husband number one of three as its cinematographer and co-star, Deren also wrote to Katherine Dunham, the Black dancer and choreographer who became one of the form’s great anthropologists. Deren was hired as Dunham’s personal assistant and de facto press agent while the latter’s fieldwork took her around the Caribbean, studying the African diasporic dance traditions as realized in Jamaica, Trinidad, Martinique, and Haiti. Deren became fixated on Haitian Vodou, traveling to the country four times between 1947 and 1954 to document and participate in its rituals, and to produce an ethnographic film about them. In 1961, at the age of 44, Deren died of a brain hemorrhage. In the years leading up to her death, she had become dependent on the sleeping pills and amphetamines prescribed by Dr. Max Jacobson, who by that point was regularly injecting JFK at the White House.

2. I often wonder how the trajectory of rap music in the 2010s might have been different if A$AP Rocky had never taken molly. Born roughly two months after Follow the Leader came out and named, by his Barbados-born father, after Rakim, hip-hop’s first and greatest integrator of hypertechnique and spiritualism, Rocky was hailed on his 2011 debut as a symbol of rap regionalism’s demise. He wasn’t that, but his determined recreation of sounds from Houston and Memphis revealed considerable marketing acumen (borrowed from his co-conspirator, A$AP Yams) and the natural flow of aesthetic tics, onto and off of Manhattan, that had existed for decades. What he actually promised was a major-label rap ecosystem that would support the mining of discarded or forgotten styles in ways that revived rather than obscured the source material; instead, his increasingly expensive and increasingly gestural work became dictated, to an embarrassing degree, by whichever drug he decided was in vogue: garish maximalism that tried to approximate MDMA’s enveloping tingle, LSD-inspired pretensions swiped from 1970s glam rock. At the height of his potency (but not his fame), shortly after he had cashed his $3 million advance check from a Sony subsidiary, Rocky found himself in a feud with members of Raider Klan, a collective of young rappers and producers from the outskirts of Miami. The Klan had become obsessed with Memphis rap from the ’90s, specifically Three 6 Mafia and their totemic Mystic Stylez, and made a brand of ultra-lo-fi rap that buried its exuberance under distorted production that sounded like a haunted video game and became tremendously popular on YouTube and on Tumblrs where it was posted under processed photos of guns and palm trees.

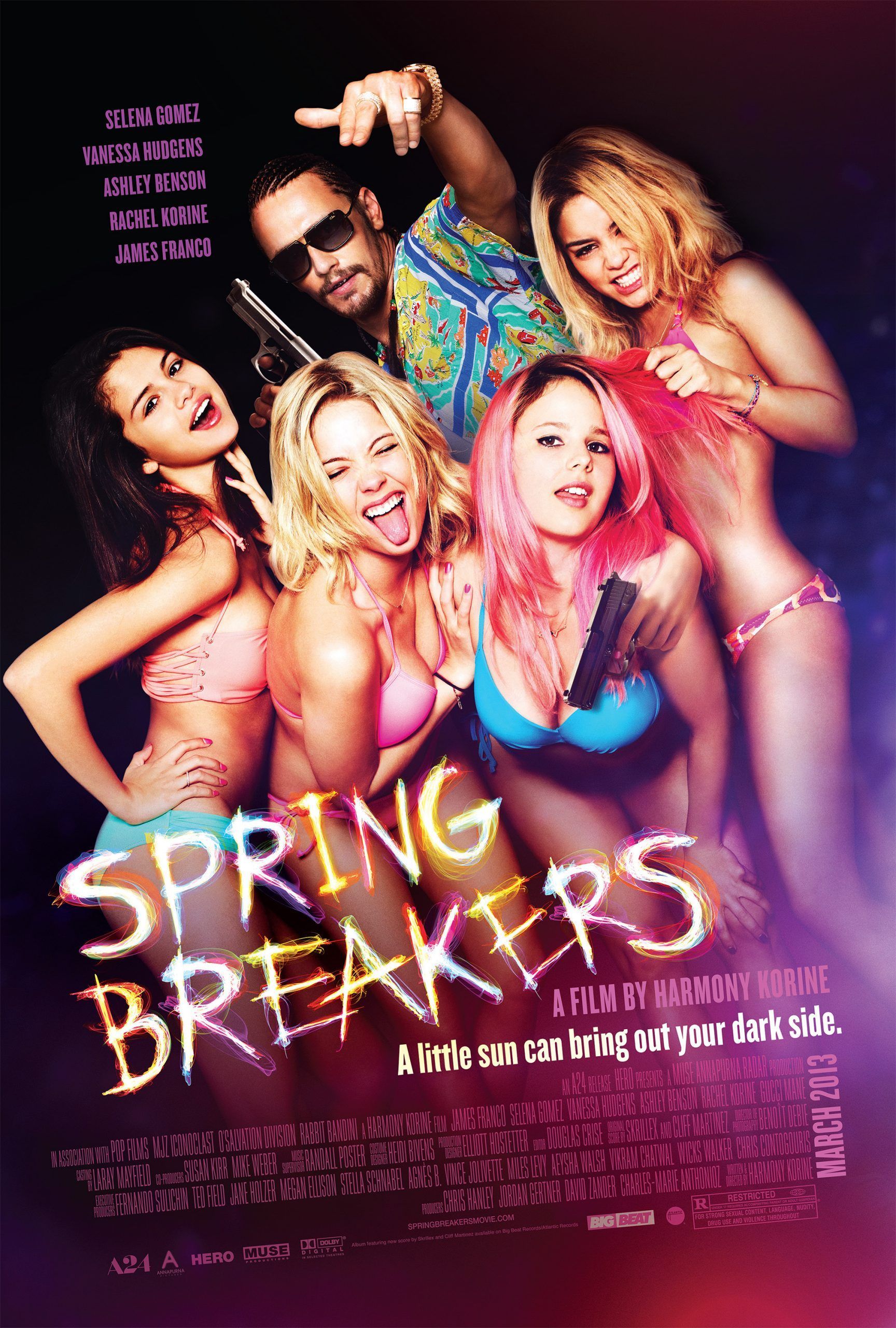

3. Somewhat improbably, it takes an hour for any white character in Spring Breakers (2013) to utter a racial slur. When it finally happens, it’s out of the mouth of James Franco, who plays Alien, a rapper conspicuously modeled after Riff Raff, a talented and charismatic MC whose public performance always seemed to teeter—gleefully—on the edge of minstrelsy. By this point in the film, Alien has played a raucous concert for a predominantly white crowd of spring breakers, who have flocked to the scuzzier parts of the Florida coast to reenact what they saw on MTV in grade school. The vanity plates and the gaudy jewelry and the entourage and the guns and guns and guns and guns and guns and guns and guns suggest a lot of money; it’s evident that a little of this is from rapping, a lot from hustling. He loves showing off all of this to Candy, Brit, and Cotty (Vanessa Hudgens, Ashley Benson, and director Harmony Korine’s wife, Rachel, respectively), three self-consciously provocative girls who have just watched their meeker friend, Faith (Selena Gomez), pull the ripcord and take a bus back to the college they all attend. Alien had perched like a vulture in the back of the courtroom as the four girls were arraigned after a party broken up by the police; he bailed them out; he took them to a dilapidated pool hall whose Black crowd shook Faith to her core. He smiled a lot, he drawled. He talked about being the only white kid in the neighborhood where he grew up—true, perhaps, but wielded like a moral cudgel. When he and his former best friend, Big Arch (Gucci Mane, one of rap’s great 21st-century stylists), were kids, they would rob naive vacationers on their city’s boardwalk. But after a confrontation in a strip club, where it becomes clear that Alien’s drug- and gun-running operation is infringing on Arch’s larger one and Arch tells him to “buy a fucking surfboard” and disappear into the ocean, Alien goes back home, where the epithet flies. The girls giggle as he pounds his chest, then they kiss him, then they hold his own guns to his head in what could be an execution-style shooting or foreplay.

4. “After” is tricky, actually. Korine’s manipulation of chronology in Spring Breakers is subtle but important—precisely in how it renders unimportant the cause and effect, the moral Rubicons crossed. The film’s plot, uncomplicated in any arrangement, is not meant to be decoded or diagrammed but to be felt. It is never quite clear which eruptions of terror or ecstasy happen in what order, which euphemizing voicemails for grandmothers are what therapists might call positive self-talk and which are really pleas for the cocooning comfort of youth, of normalcy. The return to images, often of violence—of the muggings the three girls commit with Alien near the beach, of the Chicken Shack heist they pull off with a hammer and squirt guns to fund their spring break trip, the murder of a dozen Black men in the film’s climax—makes them seem ghastly but dreamlike, like video games, like fun.

5. Contrary to the clean lines of demographic and ideological divisions drawn by political consultants by the end of the W. Bush years, everything in the United States happens at once and on top of itself. In Spring Breakers’ first act, when the girls are still at school, signifiers of white conservative defiance and Black cultural products collide, the hunger for each making the other seem more vital, more dangerous. Cotty tests her squirt gun in front of a poster of Lil Wayne; videos of Kimbo Slice light up dorm rooms from laptops. The girls speak in an affected slang, hypersexual even away from the gaze of their male peers—drawing hearts around phrases like “I WANT PENIS” as they ignore a lecture about postwar redlining. The pastor who charms Faith wears Ed Hardy and Affliction and has neck tattoos and has definitely watched those same Kimbo videos, maybe to critique his form.

6. Spring Breakers was the first significant feature film released by A24, the independent film production company that has become one of the most influential forces in film, founded by three veterans of a multinational investment bank. One of its signatures is the use of drifting pastel interstitials present here and in Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight, one of the studio’s two Best Picture winners. But in Korine’s film, the colors do not just represent lushness, life, regeneration—they bleed continuously into cold, sober mornings after. About a half hour into Spring Breakers, the girls are at a cliché-riddled motel party (foam, cocaine, keg stands) soundtracked by Birdy Nam Nam’s “Goin’ In (Skrillex “Goin’ Down” Mix)”—which would soon become the scaffolding for A$AP Rocky’s “Wild for the Night”—when the police drag them, along with many other partygoers, to jail. The teal glow that suffuses lockup is indistinguishable from the pool where Faith decides that her life has never been so perfect.

7. Sometime in the ’70s, Johan van der Keuken, the Dutch documentarian, said, “The camera is heavy […] It’s a weight that matters and entails that the movements of the machine can’t take place freely, every moment counts, [has weight].” It was an astute observation for its time and a wonderful little double entendre as film equipment was, truly, quite cumbersome, and the difficulty and novelty of filming and being filmed made each projected image seem carefully chosen. Today, as in 2013, this is no longer true. Cameras are literally and spiritually ubiquitous; our senses of self are irreversibly warped by concerns as abstract as the awareness of a global surveillance state and as mundane as the half dozen iPhones you can likely spot if you look up from the one on which you’re reading this. Though most of Spring Breakers is presented in bold, oversaturated colors, with shifting film speeds and vaguely hallucinatory effects, Korine lapses very briefly—in the motel party scene, just before the cops interrupt and trigger the ascent/descent into heaven/hell—into handheld camcorder footage. It’s a reminder: we are always both watching and watched, performer and critic, raw material and parasite. Spring break forever.

¤

LARB Contributor

Paul Thompson is a senior editor at the Los Angeles Review of Books. He has written for Rolling Stone, GQ, New York, Pitchfork, and The Washington Post, among other publications.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Going Klear: A Glass Onion Franchise in the Wild

J. D. Connor asks why Netflix spent $450 million to acquire the “Glass Onion” franchise.

It’s All Pastiche: On Todd Field’s “TÁR”

Paul Thompson reviews Todd Field’s “TÁR.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!