No Accident: On Two New Books About the Occupied Territories

David N. Myers reviews Nathan Thrall’s “A Day in the Life of Abed Salama: Anatomy of a Jerusalem Tragedy” and Mikhael Manekin’s “End of Days: Ethics, Tradition, and Power in Israel.”

By David N. MyersMarch 1, 2024

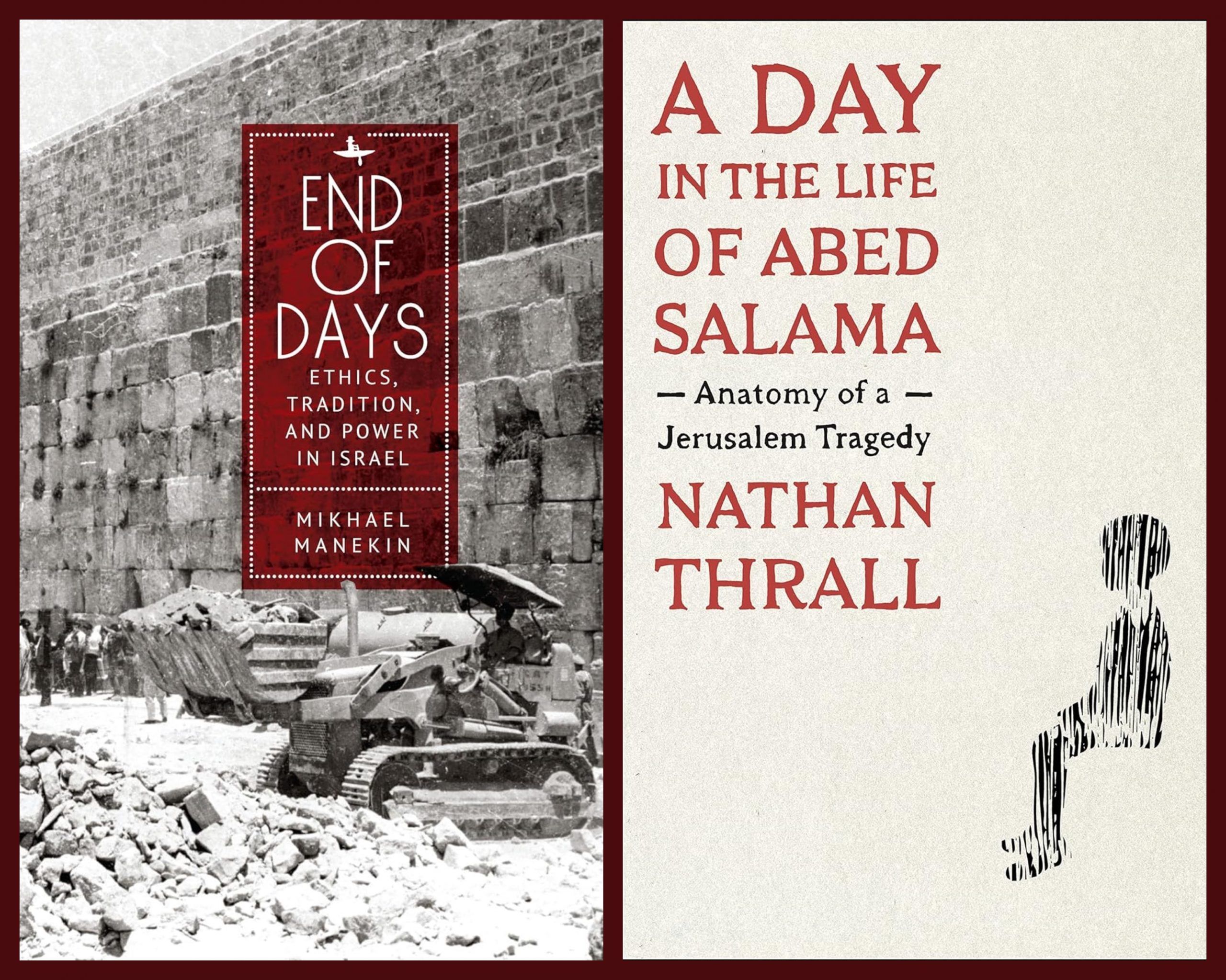

A Day in the Life of Abed Salama: Anatomy of a Jerusalem Tragedy by Nathan Thrall. Metropolitan Books. 272 pages.

End of Days: Ethics, Tradition, and Power in Israel by Mikhael Manekin. Academic Studies Press. 146 pages.

ON A COLD February morning in 2012, marked by driving rain and high winds, a terrible collision occurred on a road outside Jerusalem. The accident was caused by an irresponsible and undertrained semitrailer truck driver with 25 prior traffic violations who lost control of his vehicle, which flipped over and swung into a bus carrying school-age children. The crash produced a huge conflagration that would consume the bus, leaving many children burned and six of them dead, along with a teacher.

It is this tragic event that stands at the center of Nathan Thrall’s book A Day in the Life of Abed Salama: Anatomy of a Jerusalem Tragedy (2023), which is based on an extraordinary article in The New York Review of Books in 2021. And it offers a whole microcosmic world of Palestinians (and a few Israelis)—the list of characters at the beginning of the book numbers more than 60—whose lives intersected on that bitter morning in February. Thrall meticulously reconstructs their worlds, exposing readers to deep class and family differences, rivalries between clans and towns, painfully unrequited love, conventional and unconventional gender roles, and, above all, searing tragedy.

Most poignantly, he follows the paths of two young boys from the village of Anata in the West Bank: Milad, son of Abed and Haifa Salama, and Salaah, son of Nansy Qawasme and Azzam Dweik. Both were filled with excitement at the prospect of a school outing to a play area called Kids Land, although each had a family member who had a premonition that a tragic fate awaited them. Both children were burnt beyond recognition in the fireball that engulfed the bus following the accident. The Jaba road on which the bus traveled was initially constructed for Israeli settlers to allow them to bypass the city of Ramallah, but it had become over time a route traveled by Palestinians. The road was carved out of the Judean Mountains, with the towns of Jaba and a-Ram on either side of the cliffs. Because its curves and slope had led to many accidents, it was known as “the death road.”

The genius of Thrall’s book lies in its ability to unearth the lives, aspirations, and sentiments of his protagonists—parents, teachers, drivers, emergency personnel, and children brought together by the accident. Thrall conveys the aching and unconsummated love between Abed and Ghazl, two teenagers of the two largest families, whose preordained route to marriage in the tradition-driven society of Anata was disrupted by the ill-intentioned intervention of Abed’s cousin. He writes of the frantic efforts of two of the medical personnel who arrived at the scene of the terrible accident: Huda Dahbour, a Lebanese-born Palestinian physician who worked for the United Nations Relief and Work Agency (UNRWA), and Eldad Benshtein, a Russian-born Israeli Jewish medic who lived in the West Bank settlement of Tekoa. And Thrall describes with almost unbearable apprehension the terrible hours after the crash, when Salaah’s family searched hospitals in Ramallah and Jerusalem for the young boy with a Spider-Man backpack—before turning its fury on Salaah’s mother for allowing him to go on the trip.

And yet the most important character in A Day in the Life of Abed Salama does not utter a word or appear at the site of the accident or in a hospital. This character is essential to understanding the circumstances in which the collision occurred and the delays in getting to the bus and extricating the children. Its name is Occupation, the term that has been attached to Israel’s 57-year rule over the West Bank since the Six-Day War in 1967. Some supporters of Israel continue to deny that the intense security and intelligence grip it holds over three million Palestinians in the West Bank amounts to an occupation. But already a few months after the war ended in 1967, no less a figure than the Israeli Foreign Ministry’s legal advisor, Theodor Meron, determined that the Fourth Geneva Convention’s holding that an occupying power shall not “transfer parts of its civilian population into the territory it occupies” imposed “a categorical prohibition” on Israel—that is, it could not move civilians from Israel to the conquered territory on a permanent basis. Meron’s opinion was rejected by Israeli politicians at the time and has been marginalized ever since. In fact, with the support of every Israeli government since 1967, some 500,000 Israeli Jews have settled in the West Bank, effectively erasing the Green Line that served as a de facto border prior to 1967.

To protect them, and to push back against the claims of an illegal occupation, Israel has entrenched itself into the territory through a vast network of settlements, military bases, industrial zones, and government institutions. At the same time, it has set in place an imposing regime of control—checkpoints, nighttime raids, adjudication in a Kafkaesque system of military courts—marked by daily dehumanization and frequently brutal treatment of Palestinians. The veil of protection the system provides to Jewish settlers permits them to act with impunity, often engaging in violent and even murderous assaults on their Arab neighbors.

The overlapping web of security controls that Israel has laid down in the West Bank explains the delayed response to the fatal bus crash, which might have cost additional lives. The location of the crash was in Area C, the territory designated in the 1995 Oslo II Accord as fully under Israeli control. Area C constitutes 60 percent of the land of the West Bank, with the rest designated as Areas B (shared Israeli and Palestinian control) and A (Palestinian control). The person who drew the maps dividing this territory, a retired Israeli colonel named Dany Tirza of the Israel Defense Forces, makes an extended appearance in A Day in the Life of Abed Salama. He was the person responsible for designing the separation barrier (known in Palestinian circles as the “apartheid wall”) that closes off the West Bank from pre-1967 Israel—a 40-mile towering wall, supplemented by a system of “fences, trenches, barbed wire, cameras, censors, access roads for military vehicles, and watchtowers” that totally closed off some Palestinian communities and made access to them extremely difficult.

The system of control that Tirza helped to create complicated the passage of emergency personnel to the site of the crash. Area C was under complete Israeli authority, but Israeli authorities were nowhere to be seen. The first paramedic to arrive on the scene, Nader Morrar from the Palestine Red Crescent, managed to avoid the usual traffic delays at checkpoints and arrived 10 minutes after the accident. He encountered the bus engulfed in flames and two people lying on the ground. He made a decision on the spot that they should be transported to Ramallah, because a trip to a hospital in Jerusalem would require waiting at a checkpoint before transferring the patients to an Israeli ambulance. Fifteen minutes later, the first Israeli, Eldad Benshtein, made his way to the site. Several minutes later, the first fire trucks, from the Rama military base, arrived. After the firefighters had doused the blaze, they determined that there were no more bodies on the bus. All had been evacuated already by volunteers who happened onto the Jaba road crash. The evacuees included the two young boys, Milad and Salaah, whose families searched desperately for them in hospitals in Ramallah and Jerusalem. Over the course of several excruciating hours, Milad’s and Salaah’s parents would come to learn that the charred bodies that could at first not be identified were those of their sons.

The tragedy that Nathan Thrall depicts is, in the first instance, a family tragedy, marked by the unendurable loss of two young children and the resulting sorrow, bitterness, and recrimination by one parent against the other. In its power and poignancy, it calls to mind the extraordinary and lightly fictionalized account of bereaved Palestinian and Israeli parents in Colum McCann’s mind-altering 2020 novel Apeirogon.

But it is above all the tragedy of a society under occupation, without freedom of movement, rights of citizenship, or the ability to breathe. In this regard, A Day in the Life challenges us to rethink the designation of the crash as an “accident,” a term that suggests happenstance and chance. The road on which the bus was driven, the fear of Palestinian medics about acting in Area C, the delayed arrival of Israeli medics, and the lack of overall crisis management by Israeli authorities all suggest a system designed to control, subordinate, and treat Palestinians as lesser subjects. The “accident,” Thrall leads the reader to conclude, was not an accident.

In his important 2006 book on the origins of the occupation, The Accidental Empire: Israel and the Birth of the Settlements, 1967–1977, Gershom Gorenberg notes the unlikely convergence of political enemies and the diverse security and ideological considerations that led to the rise of the settlement movement in the West Bank. But the question of how accidental the empire was remains an open one. Was it preordained that the Jewish state would seek additional territory to satisfy its sense of historical mission by recreating the boundaries of biblical Israel? Did the assertion of sovereign Jewish power, as represented by the state of Israel, necessitate the subjugation of Palestinians in that territory?

Israeli activist and thinker Mikhael Manekin offers a textured response to this question in his cri de coeur, End of Days: Ethics, Tradition, and Power in Israel (2023). This slim volume, part memoir and part manifesto, brims with bold insight and deep learning, much of which is mobilized to promote a vision of a Jewish ethical tradition at odds with the performative and often callous display of power by Jews in Israel today. Manekin recounts early in the book a powerful moment when he, as a soldier in the West Bank, realized the dehumanizing effects of that power: he locked eyes with an elderly woman whose house the army had taken over and in whose garden he was urinating. This encounter jolted him to the core: “If there was one moment in my life at which I knew in a single instance, as clear as day, that I was desecrating God’s name, it [was] then.”

Manekin is a person of faith who is profoundly troubled by the intoxicating embrace of an ethos of power and vengeance by fellow religious Jews in Israel. He is well versed in the thought of leading rabbinic expositors of the tenets of religious Zionism, for whom the creation of the state of Israel was an act of divine intervention that rendered the new polity sacred. In End of Days, he discusses how that view of a sacralized state can inculcate a sense of supremacy and insensitivity toward non-Jews, especially Palestinians. Moreover, as he shows in his analysis of a prominent Israeli rabbi, Shaul Yisre’eli (1909–95), the theological politics of religious Zionism can lead to a moral Manichaeanism that justifies retribution as a fundamental right issuing from Jewish power. As Yisre’eli wrote, “there is no obligation to abstain from revenge operations out of a concern that innocent people will be harmed, for we are not the instigators, but instead, they are, and we are blameless.” He wrote this in the wake of an event 70 years ago, in 1953, when the IDF, led by Ariel Sharon, undertook a retaliation operation in the Palestinian town of Kibiyeh (also spelled Qibya). The catalyst for the assault was the penetration of two terrorists from Kibiyeh into Israel, where they made their way to the town of Yehud and murdered a Jewish women and her two children. In response, the IDF attacked Kibiyeh in a night raid and killed nearly 70 residents of the town.

Whereas Rabbi Yisre’eli justified the raid, another religious Zionist, philosopher and scientist Yeshayahu Leibowitz (1903–94), wrote a famous essay, “After Kibiyeh,” in which he pointed to a category error that helped justify the IDF massacre:

[T]he events at Kibiyeh were a consequence of applying the religious category of holiness to social, national, and political values and interests […] The concept of holiness—the concept of the absolute which is beyond all categories of human thought and evaluation—is transferred to the profane.

Manekin’s moral stance echoes Leibowitz’s criticism of the way the state’s power politics was wrapped in the cloak of religion.

But Manekin departs from Leibowitz on a key point. Leibowitz maintained that “morality does not admit a modifying attribute and cannot be ‘Jewish’ or ‘not Jewish.’” Manekin rejects this view—and, even more vigorously, that of Shaul Yisre’eli. His book excavates a countertradition that promotes a Jewish ethic, a Torah, of nonviolence. He does so by drawing on a diverse array of modern rabbis including the Chafetz Chaim (1838–1933), the fascinating Aharon Shmuel Tamares (1869–1931), and the towering American decisor Moshe Feinstein (1895–1986). Throughout the book, he also relies on his maternal grandfather, whom he never knew but after whom he is named, and whose letters reflect the ideal type to which the grandson aspires: “[A] Jew for whom Jewish identity is not rooted in national pride or sovereignty but rather in humility and compassion.”

Thrall’s and Manekin’s books offer compelling insight into the specter of unrestrained Israeli power, frequently justified by recourse to Jewish sources. Notably, both volumes were written before October 7, 2023, and focus on the excesses of power directed against Palestinians in the West Bank, where violence by Jewish settlers has reached its highest level ever—not surprising given the support provided to them by current Israeli cabinet ministers who are overt anti-Arab racists.

October 7 was a day that left the deepest of stains on the human soul. The unimaginably brutal massacre that Hamas perpetrated on innocent Israelis permits no justification, despite the attempts by apologists to explain it away or even deny it. In response to the massacre, the twin forces of Jewish power and vengeance were unleashed in the massive Israeli retaliation. The staggering destruction of life and property that the IDF has wrought in Gaza forces to the surface an inescapable and painful question: will the experiment in Jewish power that Israel represents—and which Thrall and Manekin brilliantly dissect in their respective books—consume not only the declared Palestinian enemy but also the Jews whom it is supposed to protect? The threat it poses today is at least as much moral as physical. And tragically, one is led to conclude from these two accounts that it is no accident.

LARB Contributor

David N. Myers is Distinguished Professor and Kahn Chair in Jewish History at UCLA, where he directs the Luskin Center for History and Policy and the UCLA Initiative to Study Hate.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Beyond the Green Line: Imagining a Just Future

Julie E. Cooper explores the collapse, in the wake of October 7, of traditional Zionist narratives about the presumed protections of the Jewish...

The Case for Progressive Zionism

Can you be both a Zionist and a progressive?

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!