Nightmares Worth Indulging: On Feminist Press’s “It Came from the Closet”

Grace Byron reviews “It Came from the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror” from Feminist Press and editor Joe Vallese.

By Grace ByronNovember 4, 2022

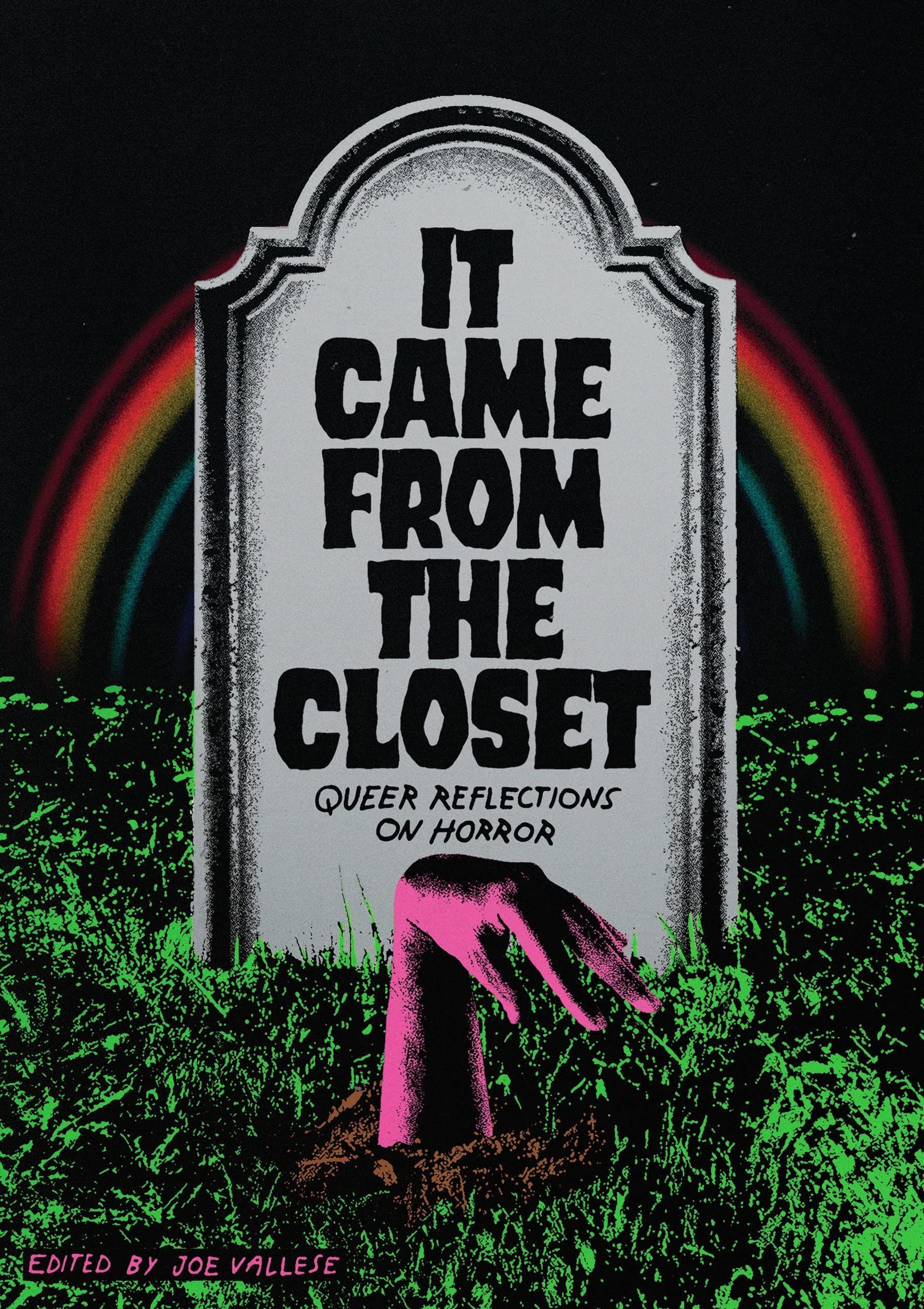

It Came from the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror by Joe Vallese. Feminist Press. 400 pages.

WATCHING THE BIRDS next to an unrequited crush, drinking cheap rosé, is not my idea of a good date — but it used to be. In her essay, “Loving Annie Hayworth,” Laura Maw describes such a date in gnawing detail, from the dizziness to the coarse carpet to Annie Hayworth’s husky voice. I had a similar experience in high school. My crush summoned me to watch The Silence of the Lambs (1991), something I’ve never quite gotten over. Eventually, I left to wander the suburban neighborhood alone at night, unable to stomach the skin suits and bloody elevators.

Maw’s is one of 25 essays in It Came from the Closet, a new collection from Feminist Press. In his introduction, editor Joe Vallese asks, “[H]ow are we to think about the complicated relationship between the queer community and the horror genre?” Vallese notes that all the contributors “convey a rich reciprocity, complicating and questioning as much as they clarify.” In other words, some of the essays will see horror films as nightmares worth indulging, while still interrogating what the genre gives and takes from queer people.

Ever since (and surely before) Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick offered queer readings of homosociality in Dickens, a certain kind of essay was born. These kinds of queer essays excavate the subtext of dominant culture. The mainstream 2009 film Jennifer’s Body, after all, inspired lesbian titillation and launched a thousand lavender wet dreams. Earlier this year, the father of body horror, David Cronenberg, declared that “surgery is sex” in Crimes of the Future, a few years late to the trans tipping point.

The modern clickbait version of this queer essay follows a familiar, rather heterosexual timeline. Authors inch forward in their journey towards revelation or acceptance, while some cultural object serves as the vehicle for their transformation. Subtext is often bent into a blunt instrument, rather than serving as a portal. This type of queer essay rarely ruptures our critical understanding of either the identity or cultural object in question.

It Came from the Closet presents a subgenre of the queer essay: the horror film as reclaimed abjection. It’s nearly a trope nowadays that queer people identify with the abject, as they themselves have been made abject. Horror films, or so it goes, allow queer and trans people to see their own reflections, as through shattered glass. These distortions allow for play, reclamation, and expansion. Certainly, plenty of queer writers have used the demonization of queer and trans people in popular horror as a starting point for their own work — Gretchen Felker-Martin, Davey Davis, Rivers Solomon, John Waters, and Ethel Cain all come to mind. Then, of course, there’s Ryan Murphy, the television auteur with a franchise dedicated to the meeting of camp and horror. (His most recent television project fumbled the abject through its unsavory attempt to resurrect American serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer.)

Nearly every essay in It Came from the Closet chronologically charts a queer person’s history alongside their chosen film, alternating between the personal and the ghoulish. Maw’s moving essay analyzes subtextual lesbian currents in The Birds (1963). Addie Tsai pens a stark confessional on the horrors of body switching in both 1988’s Dead Ringers and in her own life. Sumiko Saulson connects the dots in an essay on Black community, housing projects, and Candyman (1992). And in “Sight Unseen,” Spencer Williams charts her early video art and transition alongside the trans woman specter of the Blair Witch (from her eponymous 1999 film): “The camera is like a ghost you can hold in your hands.”

Throughout the collection, all of the expected links are made — the AIDS crisis, internalized homophobia, sexual displacement, Christian morality, and gory rebellion. “As it turns out,” Grant Sutton writes, “being raised in a homophobic, misogynistic, racist culture forces you to behave in sociopathic ways.”

Still, there are some wonderful off-road pieces that twist and turn with skeletal precision. Carmen Maria Machado’s excellent essay reads Jennifer’s Body not as a lesbian classic but as a film about parallel desire. Zefyr Lisowski’s essay on The Ring (2002) draws on disability theory to dissect neglect, care work, transition, and the medical industrial complex. Jude Ellison S. Doyle skewers body-horror politics deftly by remarking, “There is a difference between feeling uncomfortable with your own body and having others proclaim how uncomfortable they are with you.” It reminded me of my bout with COVID-19 when I buried myself in Cronenberg films. When the body is already alienated, why not take it further? Doyle points out that Cronenberg’s body horror is best when he tackles male sexuality, as in his anal-obsessed 1996 film Crash.

Other essays in the collection go down unlit stairwells I would rather have avoided. Will Stockton delivers a grim tale using the possessed doll Chucky, from the 1988 film Child’s Play, as a through line to discuss his foster child’s behavior. It is a difficult, voyeuristic piece of work. All the essays in this collection that touch on the Sleepaway Camp franchise struggle to deal with the transphobic final shot in Sleepaway Camp (1983). I would welcome a more nuanced read on Sleepaway Camp’s conflation of child abuse, gender, and violence. If the camp genre, as Viet Dinh asserts, is about hovering outside of morality, how does building an identity on reclaiming the boogeyman affect the psyche?

S. Trimble answers this question in their essay “A Demon-Girl’s Guide to Life” by claiming that horror is “about doing gender badly.” They reread The Exorcist (1973) as a text on running afoul of typical white-girl gender norms, a reparative reading that allows for more space to explore patriarchy. Sedgwick’s idea of reparative reading anchors most of the essays. A reparative reading finds the good even in the most callous of texts. Where others may see only pain, a reparative reader finds the crack in the apocalypse and chooses care among the ruins. A sinking ship is the perfect cruising spot, so what’s left to lose?

There can be a patriotism to this kind of writing, to queerness as an inherent morality. During a recent reading at the Brooklyn Museum in celebration of the book, Machado and Sarah Fonseca spoke about the “deliciousness of subtext,” and numerous young lesbians took the audience Q and A as a time to ask questions about queerbaiting. Machado and Fonseca had little patience for those who would cast aside camp classics like The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) for films like 2022’s They/Them. At one point, Machado pointed out that while They/Them’s politics were “perfect,” it was a “bloodless” film.

There’s a generational divide at play here, a youthful desire for utopia rubbing up against those who’ve grown accustomed to finding queerness in interstitial spaces. Once morality is mapped on top of these different positions, it becomes difficult to have a conversation about cultural value. I wonder about the young queer person for whom They/Them was inevitably a formative queer experience. Films like Rocky Horror or Jennifer’s Body prove ripe for exploration precisely because a certain subtextual extraction needs to happen. Queerness isn’t just the text itself, but the process: the conversation upon leaving the theater, the discussion that happens years later when you and a partner discover the same film inspired your individual sexual awakenings.

Some subscribe to the idea that queerness is a large rainbow-covered tent where all are welcome. Queerness is not the same as citizenship or nationality, yet it is increasingly treated as such through gatekeeping and a proliferation of hashtags and buzzwords. In her essay on ¿Eres tú, papá? (2018) Fonseca gestures at the trans text, not as a clean, clear understanding of identity, but by its function as an imaginative portal. Readers may bristle when they discover the transness of the film is ephemeral and mixed with murder. Personally, I can’t take one more call to champion something simply because it is queer: queer horror, queer mushroom-hunting, queer politicians, queer HRT subscription services.

The strength of José Esteban Muñoz’s definition of queerness from Cruising Utopia (2009) has been watered down to mean almost nothing in the discourse. In the queer essay, nearly anything can be dubbed queer as long as it relates to a narrator’s individualist relationship to their own sexuality. Once upon a time, queer did not sell products. Now it produces nationally syndicated television shows. Queer is considered a cloistered slur for freaks and academics, as Pamela Paul tried to claim recently in The New York Times. The problem is that, by entering the mainstream, queer has become an empty signifier. If at one time it was a way of moving, it is now a sticker for your laptop. The future is queer, brightly colored shirts declare, one step beyond the “future is female” pussy hat.

Muñoz predicted the political possibility of the horizon: “Queerness is not yet here. Queerness is an ideality.” Queerness was a reparative reading of the future, not one oriented around the family, the nation, or the institution of marriage.

The amount of press releases championing queer rom-coms does not bode well for Muñoz’s thinking, as queer protagonists and marriage plots are not indications of either quality or meaningful politics. Once queer meant something about the way a story was told; now it is a question of content. In the wake of Isabel Fall’s 2020 short story “I Sexually Identify as an Attack Helicopter,” many crusaders “canceled” a trans woman in the name of progressive queer politics. Fall published a short story that many thought was making a farce of gender, though as it turned out, Fall was herself a trans woman. She was expected to present a legible biography alongside her work to be judged for ethics, but since she was not an extremely online girl, she was thought to be a traitor. Similarly, before Sophie came out, Grimes accused the late producer of taking up space as a man using a woman’s name. There’s a dangerous line of thinking that argues a work of art is tied to what virtue the author can signal.

This doesn’t just reflect ungenerous reading practices but a paucity of imagination. A queer reading cannot stop and start at identification and metaphor; it is capable of giving us subtextual subterfuge. A queer reading can take the knife and slash the projection screen into a bloody pulp, revealing larger boogeymen and more curious continuity errors than previously acknowledged. To read something as queer should scar, the same way queerness can a body. The body does not go gently into the night after the changing of laws, government inaction, or an anonymous club hookup. The body learns something indelible about its place in the world. Not every queer reading must be David Wojnarowicz’s Close to the Knives (1991), but its urgency should always be felt. Queerness isn’t about your own isolated personal revolution.

During her reading at the Brooklyn Museum, Machado said she came to horror for the same reason she came to religion and, later, queerness: in search of an orgasm. A queer reading can feel like that — terrible, pleasurable, haunting. But for now, after watching The Blair Witch Project before bed, it’s time to turn the lamp back on and doomscroll a little bit longer because horror can still stir my dreamscape.

¤

LARB Contributor

Grace Byron is a writer from Indianapolis based in Queens. Her writing has appeared in The Baffler, The Believer, The Cut, Joyland, and Pitchfork, among other outlets.

LARB Staff Recommendations

I Don’t Worry About My Oeuvre: A Conversation with John Carpenter

Paul Thompson interviews John Carpenter about the state of horror, navigating Hollywood, and the movies he didn’t make.

Dreaming New Worlds: A Conversation with Ekow Eshun

Eric Newman interviews Ekow Eshun, curator of “In the Black Fantastic,” a recent speculative arts exhibit at London’s Hayward Gallery and its...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!