Negotiating the Generic Closet in the Writers' Room

In an excerpt from The Generic Closet: Black Gayness and the Black-Cast Sitcom, Alfred L. Martin Jr. explores the politics of writers' rooms.

By Alfred L. Martin Jr.April 7, 2021

The Generic Closet: Black Gayness and the Black-Cast Sitcom by Alfred L. Martin Jr.. Indiana University Press. 0

In this excerpt from my new book, The Generic Closet: Black Gayness and the Black-Cast Sitcom, I focus on the negotiations and labors of the culture industries workers I interviewed. I argue that they are attempting to work within the constraints of the black-cast sitcom’s generic closet to give new meanings to black gayness. Therefore, I want to, as Matthew Tinkcom advises, “keep in mind the forces of production under capital, particularly in terms of how capital seeks to treat all labor as undifferentiable.” In other words, I assert in this section that the labor of the writers and showrunners who want to bring black gay representation to television screens is fundamentally different from the labor of those studio executives who believe that their shows are simply what happens between Tide commercials. The writers and showrunners I interviewed are not without agency; however, their agency is circumscribed by industrial constraints.

Alfred L. Martin Jr.

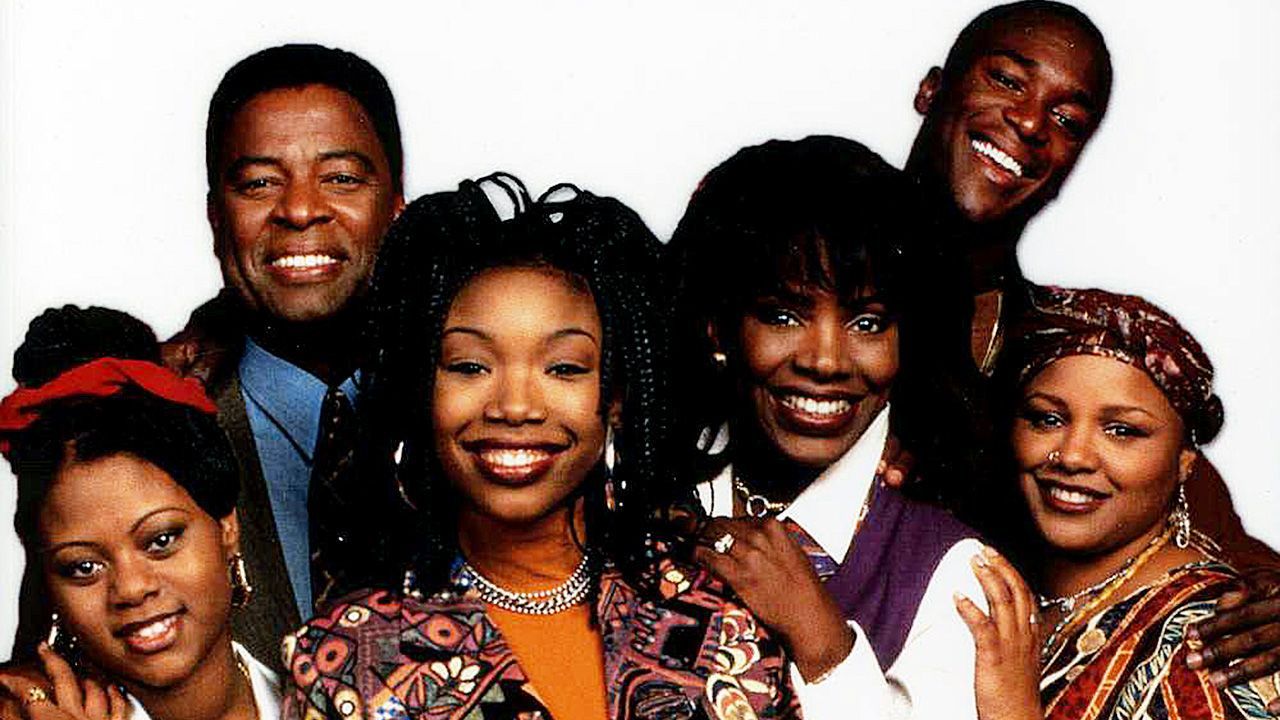

Demetrius Bady’s “Labels” script for Moesha went through workshopping that is indicative of the way television is made, however he contends that the narrative structure remained relatively untouched with one exception: in Bady’s draft of the script, Moesha attempts to kiss Omar. When he refuses her kiss, Moesha starts the rumor that Omar is gay, making the series’ hero more culpable in beginning the rumor. Such a construction of Moesha as a rumor-starter because Omar rebuffs her advances would not necessarily set him up for a “deserved” expulsion from the series’ narrative universe because the rumor would have been rooted in Moesha’s hurt feelings. Instead, Farquhar and story editor Ron Neal added Tracy, a flamboyantly black gay character, to the script, in a significant change to Bady’s original script. Bady recalls that when Farquhar and Neal received the script, they said they liked it. However, overnight they added a scene wherein Tracy’s flamboyance works to semiotically link Omar to gayness because of his relationship to Tracy. Bady recalls, “I protested because I thought they were making fun [of gay people]. They wanted the flaming queen. I protested and protested and Ralph finally said, ‘You’re not going to win this one.’ I should have been fired for how hard I fought to keep Tracy out of that script. To their credit, they did not fire me and Ralph was like, ‘I’m calling it, I’m the executive producer, so it’s staying in.’”[ii] Bady reveals the disciplinary function of network television as it attempts to engage with its workers. Protesting or pushing against dominant ideologies is not rewarded but working within the confines of the system is. Furthermore, as a precariously employed freelance writer on Moesha, Bady’s feelings about a script that would bear his name could be trumped by those with more industrial power within the writers’ room. I suggest Bady attempted to use Stuart Hall’s “reversal” transcoding strategy, which seeks to expunge “negative” stereotypes and replace them with a more “positive” image. [iii] For Bady, however, Tracy’s inclusion undercut that work.

Farquhar saw the addition of Tracy differently while acknowledging that his inclusion was a point of contentiousness in the writers’ room. He recalls,

"The one thing we wrestled with was [Omar’s] friend [Tracy], who we played in a flamboyant way. Typically, I would not have allowed that if that character were by himself, but because he was also a gay character it seemed okay. . . . It’s a balancing act. . . . So, it depends on what you need the character for. We needed that character to be [more flamboyant] because in a half hour you have to drive the point home quick. We just needed to have Moesha’s reaction and for her to start putting things together in that scene."

Farquhar acknowledges that he, like Bady, is invested in a particular kind of representational politics that recognizes that so-called flamboyant representations had become problematic in the Gay ’90s. He also affords flamboyant representations space within Moesha’s “Labels” because he can rely on a sense of balance that grants exposure to “both sides” of the gay representational coin. Farquhar only allows the “negative” representation of Tracy because its corollary—the “positive” representation—exists in the same space. Simultaneously, Farquhar insinuates that the semiotic efficacy of flamboyant gay characters is suitable for the episodic black-cast sitcom form, which requires stories and characters to be quickly, readily, and easily identifiable as a “type.” Tracy thus takes the “heat” from Moesha for starting the rumor about Omar’s sexuality. But more than that, Farquhar inadvertently reveals that both Tracy’s and Omar’s inclusion in the series is only temporary by suggesting that narrative information about them must be relayed quickly. It seems out of the question that Omar or Tracy might be a part of Moesha’s world for more than a single episode, regardless of the complexity of the story the series attempts to tell.

Bady’s experience writing “Labels” somewhat mirrors the experience of All of Us staff writers and coproducers McKinley and March, who are the credited writers for the episode, “My Two Dads.” McKinley recalls of writing the episode, “Scenarios involving that whole family, how they react, those types of things change[d].” I want to draw attention to McKinley’s suggestion that the writer’s room conversations focused on scenarios about how the family in All of Us would react to the inclusion of black gayness. These kinds of authorial negotiations become important because they set the terms within which black gayness will appear in the episode(s). For All of Us, black gayness, even in the ideation stage of script development, retains its secondary narrative status.

When March and McKinley worked on TBS’s Are We There Yet? as coproducers and writers, they still went through the typical writers’ room process. Because neither March nor McKinley was the series’ executive producer, they had to follow orders and, more generally, the direction the other writers in the writers’ room wanted an episode to take. And sometimes the direction dictated by the writers’ room and the showrunner does not always net the intended results. As McKinley details, when “the showrunner got [the script for “The Boy Has Style”] and looked at it, he said, ‘We can’t put this out. I’m a supporter of the gays and I can’t have this [episode] coming out.’” The direction that the staff writers and producers suggested McKinley and March take for “The Boy Has Style” received a different reaction when the script was fully written. McKinley and March say they knew the direction from the writers’ room would make the script’s treatment of homosexuality harsh, but they wrote it following that direction. McKinley says, “When you’re a writer you have to follow the [story] outline the room decides; you might not agree with it. I didn’t, but the script that we turned in was very harsh, a little harsher.” McKinley recalls, “At one point the father was going to come to [Cedric] and say, ‘How dare you lead my daughter on!’ We just felt that it was kind of crazy; it was almost bordering on the father almost bashing [Cedric] a little bit.” In subsequent drafts, the conversation was softened so that Nick did not appear as hostile toward Cedric’s homosexuality—a move that retains the audience’s goodwill toward him. Ultimately, the episode was revised to have Nick say that he was fine if Cedric were gay but that Cedric needed to tell his daughter so as not to lead her on; this approach is a degree of shading, but it maintains the spirit of the original idea. More than that, it retains the notion that for Are We There Yet?, Cedric’s homosexuality is about knowledge production for others—not him.

Weinberger had a different relationship to authorship because he was both the writer and the creator of Good News. He says, “I started with the idea that [dealing with a gay parishioner] was an interesting dilemma for a first-time minister in a black church given what I know about the black church’s point of view regarding gay members or just the gay community. I thought this was an interesting predicament that could be done satirically, but could also make a point, but could also be funny.” Weinberger wrote the episode he wanted and, as executive producer, did not have to compromise his vision based on other writers’ ideas. However, he was faced with other issues related to authorship and production—finding an actor to play the lead character: “Originally the part was written for Kirk Franklin. He was going to be the star of the show. He objected to the material, and I refused to change it.” This power to refuse to make script changes is a power that rested with Weinberger because he wore several hats within the series. As creator, showrunner, and writer, he wielded a kind of power that none of the other writers in this chapter had (it is also worth noting and centering his white maleness within Hollywood).

Weinberger’s approach to the difficulties with Franklin was to recast the part rather than make changes. He says that the subject matter of the episode was

"bold enough . . . that Kirk Franklin would choose not to do it because of his religious position, which I guess is a couple of quotations: one in Leviticus and one in either John or Paul’s Letters to the Corinthians. . . . We debated the theological grounds for that and went ’round and ’round. I couldn’t convince him that Leviticus was wrong and that Jesus never spoke against homosexuality. . . . Had he [Jesus] been given that issue, I think he would have sided on compassion and love as opposed to ostracizing somebody because of their sexual orientation. That was an argument that I didn’t win with Mr. Franklin. . . . That’s how David Ramsey became the [series] lead."

Even after Ramsey was cast instead of Franklin, there were still casting issues for the series because of the subject matter of the pilot. Weinberger wanted the series to feel as real as possible, and, in order to achieve this, he recruited churchgoers from Los Angeles–area churches to work as extras. He recalls,

"At one point one woman objected to the whole idea of the show. When she did, I just made a little speech to everybody expressing my beliefs and what this church [within the series] believed, that this church, at least as long as I was running [the series], it was going to be a forgiving and compassionate one, closer to what I believe Jesus would have said. . . . She was there with her daughter as a matter of fact, and she said to her daughter, 'Ok, we’re leaving.' I said that anyone who objects to this should get up and go out. 'If the show is in conflict with your religious convictions, then I think you shouldn’t be part of it.' That woman was the only one that left out of the two hundred on the show. Once we settled on the principal cast, no one else had any problems with the subject matter."

This power to dismiss cast members and extras is rooted in Weinberger’s position within the series. As McKinley, March, Banks-Waddles, and Bady suggested, even if they were unhappy with the direction the writers’ room or the showrunner wanted to take, their only form of recourse was to grudgingly go along with the changes, quit, or be fired.

As the writers and showrunners in this section demonstrate, negotiations over how to get black gayness representationally “right” is central because, on some level, they understand that they do not have (or will not insist on) the luxury of coming back to these stories to tweak them. The generic closet casts a shadow over these series. To properly “deal with” black gayness once and for all, they have to do so in ways that carefully think through the inclusion of more “feminine” or “masculine” black gay characters and the hostility series writers and showrunners produce about black gayness. As Bady discovered on his “Labels” script and McKinley and March on their “The Boy Has Style” script, sometimes the showrunner simply “pulls rank” and decides that a script should develop in a certain fashion; however, these negotiations are vital to an understanding of the generic closet and the queer politics of the black-cast sitcom. These culture industry workers are aware that, historically, black gayness has not been present within the black-cast sitcom, and they attempt to represent it—even if for only one or two episodes.

LARB Contributor

Alfred L. Martin Jr. is an assistant professor in the Department of Communication Studies at University of Iowa. Martin’s research focuses on race, sexuality, and media industries. Martin is currently completing work on his book The Queer Politics of Black-Cast Sitcoms which will be published in late 2019/early 2020 by Indiana University Press.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Disney's Disembodied Black Characters

From The Princess and the Frog to Soul, Hope Wabuke asks why can't Disney let Black characters play Black characters?

The WandaVision Cul-De-Sac

For Dear Television, Aaron Bady watches WandaVision and finds the Marvel Cinematic Universe dreaming about itself once again.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!