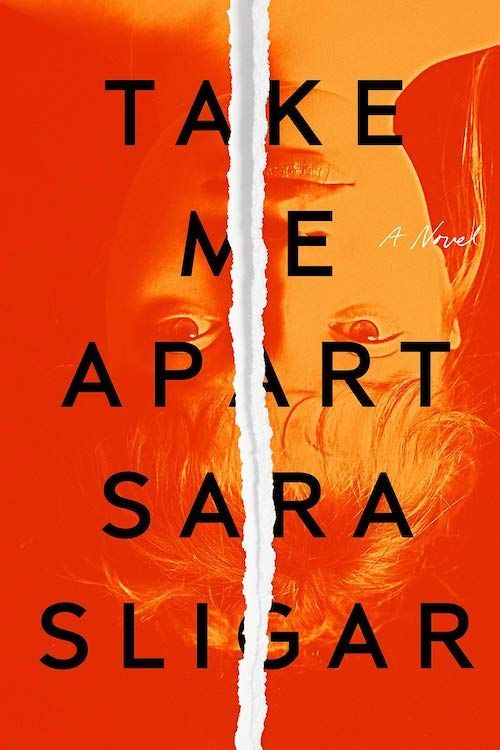

Mystery and #MeToo in Sara Sligar’s “Take Me Apart”

On “Take Me Apart,” the debut novel from Sara Sligar.

By Randy RosenthalMay 20, 2020

Take Me Apart by Sara Sligar. MCD. 368 pages.

ALL GOOD NOVELS are mystery novels. I was initially skeptical when my first writing teacher told me this, but ever since that class I’ve looked differently at literary fiction, seeing the mystery in it, and I’ve looked differently at mystery fiction, seeing the literary in it. Some novels recognize that these distinct genres don’t really exist, and that there’s just fiction. Sara Sligar’s debut, Take Me Apart, is this kind of novel. It’s billed as a “psychological thriller,” but I’d describe it more accurately — though oxymoronically — as a sun-soaked noir. Because while it does revolve around a mystery, it’s really just fiction, the kind that makes you want to turn the pages. Not necessarily to find out what happens at the end, but to find out what happens next.

Taking place over the summer of 2018, Take Me Apart is set just north of San Francisco, in a small beach town called Callinas, which doesn’t exist. (But there’s Bolinas right where Callinas is supposed to be, so.) A California transplant herself, Sligar tells her story in a close third-person — close, that is, to 30-year-old Kate Aitken. When the book begins, Kate has recently been fired from her job as a copyeditor for a paper in New York, but we don’t know why. There are hints: it has something to do with an affair with her boss, or if not an affair then something sexual; we’re told she was “on the wrong side” of news reports; she maybe got a settlement. She doesn’t want to talk about it.

After what we gather was a rough time of isolation and medication, Kate comes to live in Callinas with her eccentric aunt Louise — her mother’s sister — and placid uncle Frank. Their house is walking distance from the notorious home of Miranda Brand, a famous photographer who supposedly shot herself in 1993. Some say it wasn’t a suicide. “There’s all kinds of theories,” Louise tells Kate. One is that Brand’s husband Jake killed her. Another is that her then-11-year-old son, Theo, shot her.

Theo, now 35 years old, is Kate’s new boss. He hired her to prepare a “find aid” for an upcoming auction of Miranda Brand’s papers. Acting as an archivist, Kate will have to sort through Miranda’s terribly unorganized documents, including unpublished photographs, each of which, when sold, will bring Kate a hefty commission on top of her regular fee. For context, Miranda Brand’s photographs often sell for $400,000. In fact, her most famous photograph, The Threshold, sold for $650,000 at auction. Yes, she’s that kind of famous dead artist.

How a photograph can sell for that much money is a mystery itself. But that’s not the mystery that drives Sligar’s story. It is, rather, how Miranda Brand really died. And the clues to her death appear to be in her art. The series that first made her famous is called Capillaries, which “consists of protraits of women in everyday environments, but with a twist: their faces and bodies are caked in blood.” Later she made self-portraits of self-mutilation. In the series Inside Me, for example, “she had slashed different parts of her body and photographed them up close. A hand, sliced open. The inside of a knee, blood pooling from a horizontal slit. An ear with blood pouring out of the canal, over a diamond earring. The gristle and fat and bone of her, torn open into elegant flicks and syrupy drips.” These works are interpreted to be feminist statements. Miranda’s suicide, it seems, could have been her final art piece, the ultimate act of artistic self-destruction.

But Kate doesn’t believe that Miranda killed herself. Even though the two women never meet, Kate comes to feel “that she knew Miranda better than anyone had ever known her, because she had been forced to imagine her, because she had had to fill in the gaps.” Like literary detectives, we fill in the gaps along with her, first through letters and then through Miranda’s diary, which Kate finds while snooping in Theo’s room. Sligar effectively structures Take Me Apart with chapters alternating between Kate’s story and Miranda’s diary entries, building tension by dropping clues in each narrative, until we, like Kate, feel that if we can just get to the end of the diary, the mystery of how Miranda died will be revealed.

The novel is not all about mystery and murder, however. Like any good noir, Take Me Apart has frequent flashes of fine art, and many passages sparkle with Sligar’s style. For instance, when Kate drinks wine at a party, Sligar writes, “[S]he could taste the mineral edge. Peach and stone. And the color, as she tipped the glass, was like dissolved gold.” Such a line makes me want to drink white, though I’m a fan of red. And when Kate starts to feel herself falling for Theo, Sligar writes about “[t]he way her heart seemed to beat harder near him, like a fish yanking for its life. Only — someone having their hook in you was dangerous. It hurt when you wiggled against it. It hurt when it was removed.” Damn, I thought upon reading these lines, and then, how real, how true — that’s exactly how it is.

¤

When we meet Theo, he’s a recently divorced, rich tech guy raising two young kids, Oscar and Jemima. (Yes, Jemima. Why anyone in the 21st century would name their daughter Jemima is another mystery.) He’s stand-offish and condescending when he first meets Kate. To be fair, many people have suggested he murdered his mother, who was, we later learn, a terrible parent. At best, she was neglectful. At worst, dangerous. After Theo’s birth, she was temporarily committed for psychosis; in her diary she calls baby Theo “an ugly little beast” and admits she “thought about running a blade through his tiny heart.” So it’s understandable that, as an adult, Theo would be a jerk.

And yet, after working together in the same space for weeks, Kate understands Theo differently. In fact, she realizes she’s been misunderstanding him all along. During an awkward conversation, Theo blushes and admits he’s been harsh because he’s trying to “create boundaries.” Then it hits Kate: “All this time, she had thought he hated her, but that wasn’t it at all.” She had always found him attractive, and now she realizes that “he was attracted to her, too, and he was afraid of crossing the line.” But eventually, inevitably, they do cross a line. And so once again, Kate finds herself in a sticky situation with her boss.

¤

Some novels are called books of ideas, but Take Me Apart is a book of issues. Through the stories of Kate and Miranda, Sligar explores the sticky territory of power dynamics between men and women, whether boss and employee, teacher and student, or husband and wife. She threads a scathing feminist critique throughout both narratives, nailing all the right talking points of the current discourse.

For example, in Callinas’s one bar, Kate meets a woman named Wendy, who went to school with Theo and tells a story about once being in the Brands’ house. She remembers Miranda “saying something about how I shouldn’t do what other people say. How that was an important lesson to learn, because I was a girl, and soon I would be a woman, and it would get harder to say no. So I should practice now. Practice saying no.” This bit of advice echoes the situation Kate had at her previous job, when her boss called her into his office, took out his penis, and got himself off in front of her. This happened several times. Why did Kate keep going to his office while he masturbated in front of her? Why didn’t she tell him to stop? She can’t explain her behavior to herself. But she never said no. And for that, she is — like the victims of Harvey Weinstein — implicated as complicit in her own sexual assault.

Kate’s experiences continue to mirror Miranda’s, with the feminist strands reflecting each other. In Miranda’s diary, once she begins giving lectures about her art, her husband, Jake, says she’s “[s]pitting out a chewed-up version of feminist theory,” and asks why she doesn’t just let the art speak for itself. “Men aren’t afraid of misinterpretation,” Miranda writes in explanation. “It’s not dangerous to them. Women, we know bad things can happen when someone misreads you.” This brings to mind Margaret Atwood’s line: “Men are afraid women will laugh at them. Women are afraid men will kill them.” Putting things together, we worry that Theo might kill Kate. She must make sure he doesn’t misread her.

Some of these political bits feel heavy handed. Like at a party in Callinas, when the bartender Nikhil meets Theo and they shake hands “in that casual way men sometimes did, bringing their elbows out,” the narrator tells us that “Kate had never figured out where men learned that. Maybe the same place she learned to apologize for interrupting, or to rephrase her ideas in meetings to make them sound like they were someone else’s.” It’s right on the nose.

The riskier parts of Take Me Apart are when Sligar opens up the more ambiguous spaces of the #MeToo conversation. When Kate’s friend scolds her about her relationship with Theo, because of “all that stuff” Kate went through with her previous boss, Kate admits that yes, she is having sex with her new boss, that “it happened and I chose for it to happen.” After it happens, Theo voices concern over his and Kate’s relationship, making sure their decision to be sexual is mutual, saying, “I don’t want you to do anything you don’t really, a hundred percent, want to do.” He asks Kate what she wants. Instead of answering verbally, Kate straddles Theo, kissing him before he can say anything else. By changing Kate’s passivity into agency, Sligar avoids an easy cliché, changing what could have been a caricature into an authentically complex character. The real mystery, she implies by Kate’s behavior, is why we do things we know we shouldn’t do.

Exploring this ambiguity may make readers uncomfortable, even upset. We prefer to set things out clearly, into neat categories of right and wrong. We want to be on the right side of history, or at least social media debates, and are maybe afraid to admit that things are more complicated than we’d like them to be. But that’s okay. As Miranda Brand writes in her diary, “Art is supposed to upset you. Art is supposed to make you feel afraid.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Randy Rosenthal is the co-founding editor of the literary journals The Coffin Factory and Tweed’s Magazine of Literature & Art. His work has appeared in numerous publications, including The Washington Post, The New York Journal of Books, Paris Review Daily, Bookforum, Harvard Divinity Bulletin, The Daily Beast, and The Brooklyn Rail. He is a recent graduate of Harvard Divinity School, where he studied religion and literature, and currently teaches writing classes at Harvard.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Convincing Fake: On Emily Beyda’s “The Body Double”

Art Edwards reviews “The Body Double” by Emily Beyda.

No Childhood to Lose

Jan Cherubin reviews a debut novel about the legacies of childhood sexual abuse.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!