Monumental Ignorance: How Donald Trump Misuses Imagery

Trump turns traditional America iconography inside out

By Diana DePardo-MinskyAugust 28, 2020

THIS PIECE APPEARS IN THE MISTAKE ISSUE OF THE LARB QUARTERLY JOURNAL, NO.27.

LIKE SO MANY NONPROFITS AND LITERARY COMMUNITIES, MANY OF LARB’S FUNDRAISING SOURCES HAVE BEEN UPENDED. IN ORDER TO CONTINUE PROVIDING FREE COVERAGE OF THE BEST IN WRITING AND THOUGHT, WE ARE RELYING ON YOUR SUPPORT NOW MORE THAN EVER.

DONATE $5 A MONTH, RECEIVE THE MISTAKE ISSUE OF THE LARB QUARTERLY JOURNAL AS AN EPUB OR PDF.

FOR $10 A MONTH, RECEIVE IT IN PRINT.

¤

TRUMP FANCIES HIMSELF an expert image maker, but, the thing is, he is actually bad at it. Really, really bad. While he can create the photo-op equivalent of a tweet, when he attempts more complex choreography, he usually fails miserably. His cavalier overconfidence reveals a visual illiteracy as well as an ignorance of the iconography used by American politicians throughout our history. Trump’s recent engagement with monuments — including his praise for Confederate abominations — illustrates an almost total lack of understanding, either of their historic context or of their visual language.

Visual imagery, unlike verbal language, presents a plethora of information at once. Patrons, architects, and artists across millennia have developed their own syntax and vocabulary to compose this enormous flow of information into meaningful art. These languages, which long predate print, have allowed the powerful to communicate with people through composition, pose, gesture, and signifying attributes. Audiences might have different degrees of comprehension, but repeated tropes have survived and gained currency. In the West, the Classical world formulated much of this language, establishing the conventions for a variety of images, including portraits of rulers, either seated or standing. Trump has used these kinds of images as props or as inspiration for his own poses, and yet he co-opts clumsily, often modifying their forms and misconstruing their meanings.

He made his first mistake when he announced his candidacy for president. From the moment he descended the escalator in his Golden House, it was clear that he did not have the constitution to participate in the government of a republic (res publica, literally translates to “a public thing”). Trump chose to arrive from above to the level of the people, presenting himself as a kind of deus ex machina (in this case, a god arriving “on” a machine), recalling the conclusion of ancient Greek dramas when pulleys hoisted an actor above the stage, establishing him as a deity who alone could resolve the problems of those below. Trump’s initial visual presentation was later put into words. As he famously said at the 2016 Republican National Convention: “I alone can fix it.”

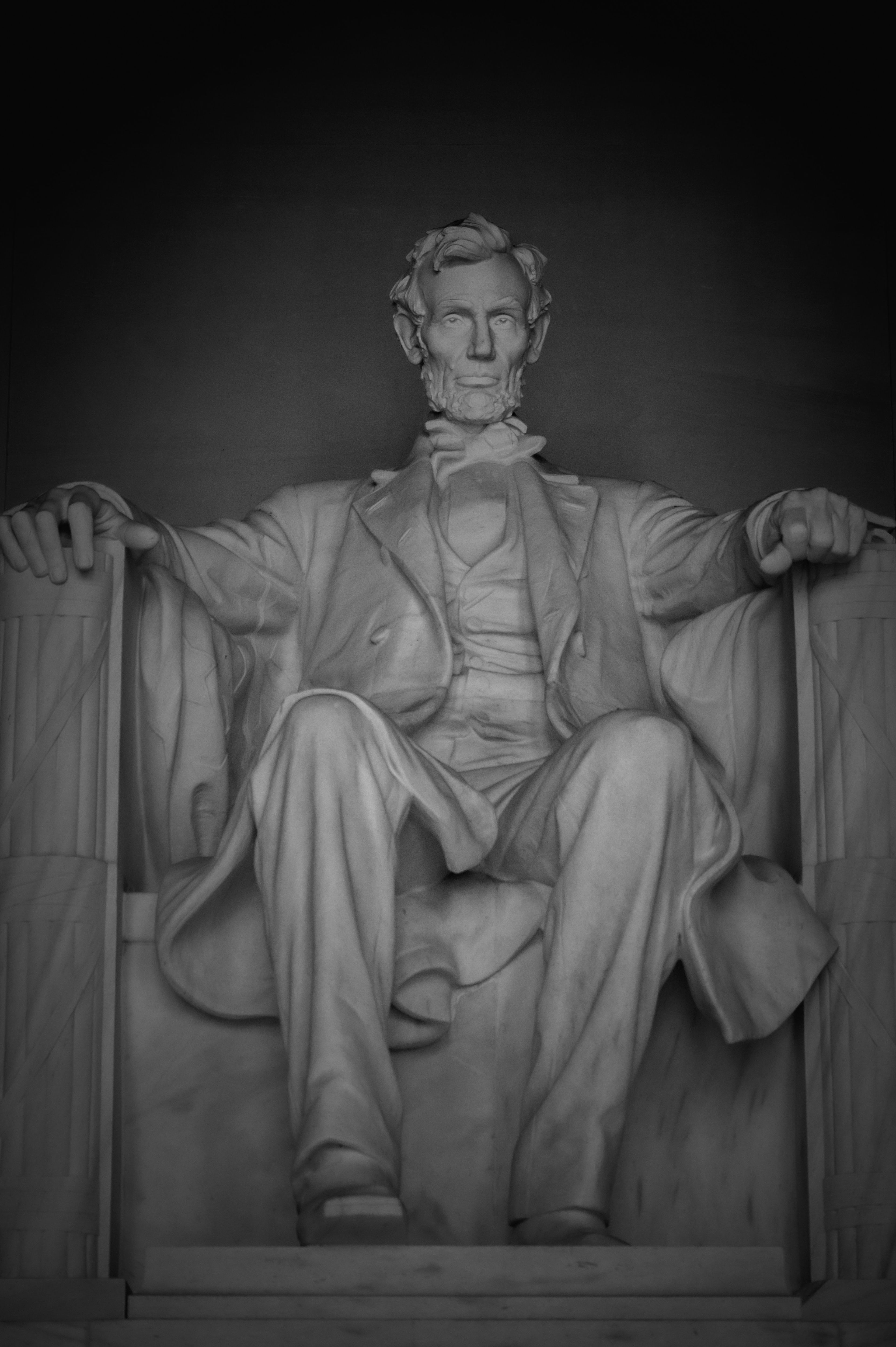

Since then, Trump has repeated this kind of performance over and over, gravely misunderstanding the significance of visual hierarchy whether in placement or scale. His most complex visual composition was more recent — a tableau at the Lincoln Memorial, crafted with the help of Fox News. The interview at the monument, held on May 3, 2020, presumably intended to associate Trump with the ideals and achievements of the 16th president. Instead, it exposed Trump and his team’s total lack of knowledge of almost everything about the sculpture’s iconography — the visual hierarchy, the typology of seated-ruler portraits, the statue’s symbolic attributes, as well as the rhetorical power of adjacency. The Founding Fathers were steeped in the history and imagery of ancient Greece and of the Roman Republic; these traditions have continued to shape public monuments throughout the early 20th century, apparently without the current administration's comprehension.

Daniel Chester French’s marble of Abraham Lincoln, completed in 1920, participated in this long history of large-scale representations of seated rulers presented as defenders of unity and justice (not all actually were defenders, but they commissioned works that used this iconography to imply they were). This way of representing rulers descended from Mesopotamian and Egyptian works from the third millennium BCE, but the most relevant precursor is a statue of Zeus enthroned, bare-chested (nudity equaled divinity; please do not tell Trump!), holding a winged Victory on his extended right palm, and supporting a scepter or staff (an emblem of peaceful rule) with his left. This prototype dates from fifth century BCE Greece, the culture identified with the foundation of Western democracy. Commissioned for the Temple of Zeus at Olympia and designed by Phidias, this lost colossus nevertheless survived, in large part, because of a description from the second century CE by Pausanias. The work presented the deity at peace and triumphant despite the ever-present specter of division: Zeus sits above a depiction of battling Greeks and Amazons. Phidias’s imagery was copied repeatedly, surviving in different iterations from Ancient Rome to Enlightenment Europe, the intellectual incubator of the US Constitution.

A version of Phidias’s work appeared on our shores in 1841, when Horatio Greenough presented his sculpture of George Washington for Congress. This portrait shows the first president, like Zeus, semi-nude and enthroned but raising his right hand and pointing to the heavens, a Roman modification of the pose, showing either deference to a higher power or proclamation. Greenough also introduced his own innovation: the triumphant general, with his left arm outstretched, returns a sheathed sword, representing his military command, to the people. This gesture is an acknowledgment of the country’s system of government: only elected legislators can declare war. The American commander-in-chief, like a Roman republican general, relinquishes imperium (military command) to the people. Greenough’s seated portrait depicts the executive branch in peace time, subject to the laws made by the people’s representatives.

Greenough’s statue, however, did not succeed with the 19th-century public, partly because he retained an ancient aspect not suited to a modern republic: nudity. Whether or not the audience understood Washington’s bare chest as emblematic of divinity, it produced visceral discomfort. Congress removed the statue from the Capitol Rotunda and eventually sequestered it in the Smithsonian (setting a precedent for relocating public art that departs from contemporary mores). Greenough’s iconographic faux pas also validates the Founding Fathers’ fear that the executive branch would be perceived — or would attempt — to rise above its coequal branches.

Daniel Chester French successfully democratized his statue of Lincoln by showing the president fully dressed in the attire of his fellow citizens and holding no attributes of power, whether staff or sheathed sword. Other than the material (marble), hierarchy of scale (Lincoln measures 19 feet tall), and seated pose, only one vestige of the antique tradition remains: fasces. Fasces, or bundles of sticks, adorn the front of Lincoln’s armrests. Carried by lictors, the bodyguards of elected officials in ancient Rome, fasces illustrated how one thin rod gains strength when bound together with its equals. In the Roman Republic, fasces functioned as symbols of the authority and the motto of the state, SPQR (Senatus Populusque Romanus: the Senate and the People of Rome). Outside the pomerium, or sacred city limits of Rome, lictors’ fasces included an axe to show the magistrate’s power over life and death. Arms, whether lictors’ axes or soldiers’ swords, were not permitted inside the pomerium unless the Senate granted a general a triumphal procession. As in the American Republic, the representatives of the people checked and controlled imperium.

Emulating Rome, the Founding Fathers chose fasces, these tightly bound sticks, as a visual representation of our motto, E Pluribus Unum (From Many, One), and fasces adorn many public buildings, including the seats of all three branches of government. Since 1789, the mace or scepter of the House of Representatives has had a fascis as its handle. On top, a globe and eagle replace the axe. The mace is carried into the House to open sessions and presides there, on a pedestal, throughout the term. Two further fasces, sculpted in the mid-19th century, ornament the wall behind the Speaker’s rostrum. These have axe heads, perhaps to emphasize that only the House, the most democratic of the three branches, has the right to declare war. At the Supreme Court, fasces appear on the west facade pediment and in the frieze above the bench of the Justices. In the White House, horizontal fasces lie above the doors of the Oval Office. These ubiquitous emblems reference the citizenry as the source of authority. The significance of this symbol is probably not obscure to many who serve in the government: during particularly important legislation or hearings, the current Speaker wears a pin replicating the mace of the House.

The Lincoln monument uses fasces to characterize both Lincoln’s accomplishments and the people as the source of political power. Seated in triumphant peace, the martyred president’s long, elegant fingers rest on top of fasces, a reminder that Lincoln preserved these United States and that the will of the people, exercised by the House of Representatives, granted him imperium to do so. Thus, in perpetuity, these ancient republican symbols both support and stand guard (like lictors) of the man who saved the nation.

In Trump’s use of the Lincoln Memorial, these vertical fasces also play a critical role. They lead the viewers’ eyes down from the majestic effigy to a diminutive Trump and his interlocutors, all perched on portable chairs. This hierarchy of scale, of importance, coupled with the symmetrical positioning of Trump and the journalists around the statue on the central axis emphasize the chasm between the two presidents: one, a lawyer who rose from poverty to power through education, eloquence, and integrity to die for our national salvation and the expansion of rights; the other, a son of privilege, with little erudition and fewer ethics, who uses bigotry to divide and denigrate the populace.

The fasces also point to a temperamental difference between the two men. Lincoln sits parallel to them, facing forward into the present and future. Similarly, the Speaker of the House and the Supreme Court Justices, stand or sit parallel, though in front of, the fasces in their halls. Backed by these ancient symbols, they shape the future with their decisions. In the Fox image, however, Trump sits perpendicular to the fasces, signaling a shift in the course of the state. His directional departure recalls that exactly 100 years ago, between 1919 and 1922, Mussolini perverted this sign of republican rule into the name and the emblem of a totalitarian regime: the fasces became a double-edged sword — or axe — with two opposing meanings. Trump and his enablers’ ignorance of visual composition, symbolism, and history created a picture which, upon close inspection, does not align Trump with Lincoln but presents him as a small man turning toward fascism.

A month after the Lincoln Memorial interview, Trump produced more overtly authoritarian images: the National Guard occupying the steps of the Lincoln Memorial (a space rendered sacred by Marian Anderson’s song, Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream, and John Lewis’s words), the Trumps blocking the statue of St. John Paul II (a pope who supported liberating Poland from tyranny and promoted interfaith harmony), and, most significantly, the image of Trump holding a copy of the Bible. These images accompanied strikingly authoritarian acts. On June 1, 2020, Trump authorized the use of violence against peaceful protestors to clear a path from the White House to St. John’s Episcopal Church (the church where Lincoln prayed during the Civil War). Trump then posed for another photo-op, standing in front of the church and looking ahead of himself, with his legs, hips, shoulders, and jaw straight and immobile. His left arm hung at his side, while his right held up an inverted Bible in a gesture reminiscent of a traffic cop signaling “stop.”

As with seated-ruler portraits, the long lineage of standing-ruler representations goes back to the third millennium BCE. Trump’s image, however, conforms to no norms. Even the serene images of Pharaohs advanced one leg, showing the potential for movement, for change. In ancient Greece, sculptors animated the entire body. Rulers, especially from Alexander the Great forward, often raised their right arms but typically the arm was higher and more curved, rarely cocked perpendicularly like Trump’s. These rulers hold scepters, spears, or swords, usually in positions implying that their battles have ended. When empty, their raised right hands point up, gesture outward in an oratory pose, or bless the viewer. Books, when incorporated, are almost never displayed on high but in positions for reading and writing or held nearer the waist as an identifying attribute or a testament of learning.

Trump’s Bible image departs from these traditions in almost every way. The stiffness of his pose emphasizes his obstinate refusal to change. His parallel legs assert that he has staked his claim and will not retreat. This stance, both militaristic and infantile, echoes Mussolini and Hitler. The sharp right angles of his raised arm, holding up the book, evoke both his difficulty with texts (it is upside down) and his opposition to the scriptural principles of peace, compassion, caring, and forgiveness in favor of worldly riches and terrestrial power. The composition also implies a complete disregard for the Constitution — first by implying, that the United States is a Christian country, when the First Amendment states otherwise, and, second, that his power comes through the Bible, like the divine right of kings, rather than from the people. Trump’s pose also suggests an inversion of the swearing in of a president, with the Bible reduced to a prop, no longer a symbol of commitment to the Constitution.

The image of Trump with his inverted Bible should serve as a reminder to future generations of his monumental failings and his threat to the Republic. Republics, like bundles of sticks, are fragile and flammable. We should be careful whom we elect.

¤

LARB Contributor

Diana DePardo-Minsky is a professional Art and Architectural Historian educated at Yale and Columbia Universities. The American Academy in Rome (The Rome Prize), the Fulbright, Kress, and Whiting Foundations have funded her scholarship. The Mellon Foundation supported her innovative classes, and The Princeton Review included her in The Best 300 Professors (2012). She is a Researcher at the Levy Institute; she organizes in situ seminars in Italy; and she has a forthcoming book on Michelangelo.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Beyond Jermag Yev Sev: A Roundtable on Armenian American Identity

Discussing Armenian American identity, citizenship and history

Dancer Just Dancing: On Literature and Leisure in 2020

Jordan Tucker discusses the racial and queer politics of leisure

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!