Modernism’s Midlife Crisis: On Justin Beal’s “Sandfuture”

Travis Diehl on Justin Beal’s biography-cum-memoir, “Sandfuture.”

By Travis DiehlSeptember 16, 2022

Sandfuture by Justin Beal. The MIT Press. 256 pages.

SANDFUTURE OPENS as Hurricane Sandy pushes the Hudson over its banks and into the gutters, sewers, and basements of Manhattan. It’s not the disaster you’d expect from a book with the Twin Towers on its cover. But the two events, superstorm and terrorist strike, are drawn in parallel, portrayed as the destinies ordained of hubristic constructions by simple physics, a gravity-defying structure returning to earth, a waterfront district of boxes filling with water.

On its face, Sandfuture is a biography of Minoru Yamasaki, one of the most famous architects of the mid-20th century and the mastermind behind arguably two of the era’s most famous and contested complexes, the World Trade Center in Manhattan and the Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis. It is also an autobiography — the story of Justin Beal, a contemporary artist and bar owner, navigating the neoliberal glass-and-HVAC city Yamasaki defined but didn’t live to see.

Beal unveils his own life alongside the architect’s, not unlike two towers. The book traces both men’s movements through their studies of lofty modernism (Beal has a degree in architecture) to the experience of inhabiting postindustrial cities, New York and Detroit. Sandfuture narrates the last 70 years of urbanism in the United States. This epic is more approachable at human scale, the way the 9/11 Memorial Museum emphasizes, American-style, the individuality of the terrorists’ victims. Beal’s book attempts a version of Yamasaki’s belief that buildings should be warm and friendly. “We must work for the uplift, the emotional quality of architecture which is man’s physical expression of his nobility,” he wrote in 1955 in Architectural Digest. “If we could attain this quality in every building, in every walk of life, no matter to how small a degree, then we will have achieved, with the tools of our architecture, the kind of environment that we so desperately need as a framework for our civilization.”

And, like architecture, Beal’s book subjects us to its author’s ego. A great many writers have spent time in archives, looked at buildings, made love, had children, changed cities. Our interest in Beal’s version of these events persists insofar as his account of midlife, bored with himself and his work, represents the mood of a country past its prime. “I felt good,” Beal writes, “but I could also feel myself slipping into repetition, buckling, as I had always assured myself that I would never do, to the pressure to produce work that could sell.” Just like Yamasaki, bending his vision to his clients’ wishes.

In Beal’s self-assessment, his artwork was mediocre — “melons cast inside blocks of plaster, a heavy slab of glass supported by lemons, or an aluminum frame wrapped so tightly in plastic that it began to bow under pressure” — although, to the point, his sculpture “grew almost entirely from questions about how bodies interact with buildings […] The work implied repression. It was suggestive, but ungenerous.”

Perhaps Beal’s life is mediocre too. Yet not anyone would, or could, write a book of this scope and cold perversion. His work is redeemed, like so many mediocrities, by its erotic projections. In one passage, he describes wanting to ejaculate on the modernist surfaces of a Swiss laboratory:

I wanted to see something spill on the pristine countertops, drip down through the drawer slides and casters out onto the floor. I wanted to push my body against the expanses of Estremoz marble or jerk off on the immaculate glass walls. There was so much precision and so much restraint, you could not think of anything other than defacing it.

The moment passes without elaboration. Beal doesn’t ever pull back entirely to reveal the whole image: a conventionally attractive, middle-aged cis white man masturbating in public, a pathetic emission sliding down the glass. All that misspent spermfuture.

¤

Beal laces the introduction with descriptions of the flotsam on the sewage-rich seas inundating Wallspace, a now closed Chelsea art gallery co-owned by his wife — replete with precise and lurid details like the wooden staircase lifting up and dislodging, the box of tampons on the shelf next to the foam blocks and glassine. Beal catalogs the weird bits of waste that, after the fireballs and floods, impress the survivors of historic events:

[P]egboards with spirit levels, spackling knives, tape measures, rolls of low-adhesive masking tape, hex keys, white cotton gloves, and utility knives hanging in neatly organized rows, gray steel shelves stacked with digital projectors and media players with international adapters, large rolls of acid-free glassine, customs forms, ammonia-free Plexiglas cleaner, a tube of mascara, a box of tampons, a lint roller, aluminum Z-clips, brass D-rings, foam blocks, an expired Oyster card, boxes of dead-stock artist publications, and stickers printed with “empty” or “fragile” or “do not open with knife” in thick bold capitals.

When the Twin Towers fall, Beal also filters the events of September 11 through his personal recollections: the time he attended a self-help seminar on one of the World Trade Center’s poorly ventilated floors; the few photographs he snapped while the upper stories burned and fumed; the warm beer he offered the NYPD officer escorting him through the cordon to grab a few things from his downtown apartment. “I was unsure how to reconcile the public fact of what had happened that morning with the role it played in my own personal narrative,” he admits. Sandfuture can be read as the author’s attempt to reconcile his personal narrative with both the destruction of the Twin Towers and the end of the rife success of which they were a metonym.

With the fall of the towers, Yamasaki earned the unenviable distinction of having not one but two of his buildings destroyed on television. Previously, Pruitt-Igoe had become, somewhat unfairly, the symbol of failed public housing in the United States. Against its architect’s plans, the housing authority shrunk windows and skipped railings. “By the late 1960s,” Beal writes, “there were more sociologists working at Pruitt-Igoe than maintenance workers.” In March and April 1972, the city gave Pruitt-Igoe residents vouchers to relocate to the suburbs (particularly Ferguson, where Michael Brown was later murdered), then dynamited the housing blocks while the cameras rolled. A few months later, the World Trade Center was complete. Ada Louise Huxtable, a prominent New York Times critic, predicted the towers would either “be the start of a new skyscraper age or the biggest tombstones in the world.”

Beal includes himself, Yamasaki, and the towers in the same circulatory humanism: buildings as bodies, artworks as bodies, buildings as artworks built for bodies. They pump and respire; materials and organisms move in and out. And buildings have pathology — they fall ill, decay, receive wounds. Buildings are born and buildings die. “The acrid air that hung over the neighborhood smelled both natural and industrial,” Beal writes,

organic and synthetic — the smoldering remains of fax machines, gold ingots, floor wax, teeth, ashtrays, water coolers, suitcases, umbrellas, fire extinguishers, doorknobs, hair, subway cars, asbestos, glass, mops, elevators, running shoes, paperclips, smoke detectors, landing gear, filing cabinets, seatbelts, newspapers, jet fuel, extension cords, fingernails, steel.

It’s an anthropomorphic vision: we make buildings for ourselves to resemble ourselves. As it should be. What a self-centered metaphor.

¤

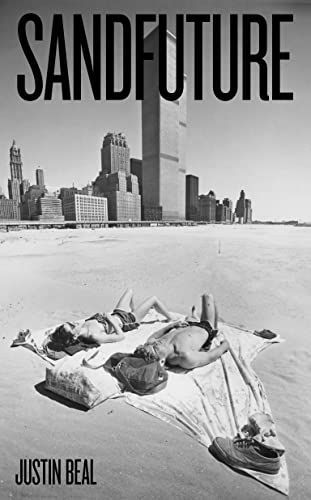

Sandfuture is an obtuse title that must have flustered those charged with marketing MIT Press’s architecture books. In part, it refers to the 28 acres of sand-covered landfill at the center of the bargain between the City of New York and the Port Authority that got the World Trade Center built: the city would cede the lease in exchange for new waterfront territory. The photo on the cover captures a sunbathing couple stretched out below the skyline on this temporary beach. A beach now but a city later: The word sandfuture inverts the situationist slogan, “Sous les pavés, la plage” (“under the cobblestones, the beach”): Après la plage, les paves. Sandfuture, we learn, is how Beal’s young daughter once described an hourglass.

In February 2008, Beal exhibited in a show at Artists Space in New York entitled Nina in Position. It was the banner year of the financial crisis. It was also the onset of Beal’s self-described crisis of confidence. Reviewing the show, Holland Cotter assigned a certain “bloodless aggression” to Beal’s work, which features a Bible verse printed on the bottom of a box of Westpac joint compound: “He has come to heal the broken hearted, To preach deliverance to the captive.” The piece extrapolates on the prophecy of Jesus Christ into the language of mass construction — to free the pale, glistening, fleshy paste from its box and bag, to smooth over the cracked.

“Nina” also happens to be the pseudonym Beal assigns his wife in Sandfuture. This in mind, the title of Beal’s show takes on the extra connotation of a sex position. Similarly, Beal’s attempts to compile the facts of Yamasaki’s love life, and his emotional dimension in general, fall flat. In the architect’s papers, he finds correspondence with assistants and Huxtable but no mention of his several lovers or three marriages. Rather than the buildings seeming human, the humans seem building-like.

These two registers, the built and the grown, squish against one another throughout Sandfuture. In one section, Beal discusses the “exactly seventy-three photographs” he took on September 11 using a 35 mm camera he had in his bag. “[O]nly the first two were particularly remarkable.” The first, a picture of some debris in the road in front of his apartment on Greenwich Street, is now in the Memorial Museum. Beal’s description recalls that of the Chelsea flooding: “[A] crumpled piece of paper burning on the street next to an unfolded cardboard compact disc case, some broken bits of acoustical ceiling panel, a piece of string, a few paper napkins, and a US passport.” His second photograph caught the plumes of fire from the second impact. When the North Tower collapsed, he writes, “I withdrew as much cash as the ATM would allow, bought a bottle of water, and continued walking north.”

In the next paragraph, his daughter is conceived:

Our daughter Zoe was conceived on a spring afternoon before Nina left for a work trip to Oslo. Nina was worried about airport traffic, but I convinced her she had time to spare. We had had rushed, practical sex on the couch with the din of Chinatown outside the open windows and the late afternoon sun raking across the living room wall. Nina left and I fell asleep.

The juxtaposition is jarring and not incidental. The towers die; his daughter lives. Sex plays a sudden, sloppy role in the book. In the early days of Beal and Nina’s courtship, they slip away to the gallery basement that floods in the book’s opening pages. “It smelled like books and concrete,” he writes. “We had sex, our hands and mouths still clumsily unfamiliar with each other’s bodies, and then lay on our backs on a pile of packing blankets, watching the floorboards creak under the weight of a visitor pacing above us.” The most erotic language in this perfunctory description of their quick fuck comes in Beal’s synesthetic characterization of the floorboards. While their daughter is hastily conceived, the light rakes the wall with greater passion than the human tenants. He describes Nina’s eyes as “granite-blue.”

Throughout the book, Beal achieves conglomeration of human-scale, flesh-and-bone-and-soul concerns with the larger, incomprehensible scale at which buildings and cities work aesthetically. The terrorist attack that the World Trade Center withstood in 1993 was seen by some as a fair critique. Beal cites a sneering Robert Campbell piece in The Boston Globe that called the bombing “a long overdue act of architectural criticism.” He continues: with the demolition of a terminal that Yamasaki designed for Boston Logan International Airport, where the two planes that struck the towers departed from, “Massport will assume the role of aesthetic terrorist.” The quaint use of terrorism as a metaphor is alarming, given that lives were lost in this “criticism,” especially so in light of what happened in 2001, when composer Karlheinz Stockhausen dared to suggest the attacks were a work of art. Beal achieves something subtler by endowing the Twin Towers with a living quality of their own, so that the hard verticals of Yamasaki’s façade resemble the blurs of people tumbling to their deaths from his thin windows.

¤

The new One World Trade Center, the most expensive skyscraper built to date in the United States, stands at 1,776 feet, nudged to this cheesy symbolic height by a 408-foot spire. Gridded with trees and punctured by twin waterfalls spilling into the old tower footprints, the new plaza is just as inhospitable as the old — perhaps even more so, in its contemporary way, with the snaking airport-style stanchions of the Memorial Museum, the names of the victims cut into the reflecting-pool railings in a tacky font, the Westfield mall filling the so-called Oculus train station.

Beal is obsessed, however, with another project: 432 Park, a supertall apartment tower needling into the skyline over the course of the book. The building is comprised of cubes, six across, six deep, and 90 high. The elevators and the permits say 85 floors, but that’s fudged. Just as the Yamasaki World Trade Center achieved unprecedented occupancy through a system of panoramic lobbies and express elevators, 432 Park’s innovations include double-height, open utility floors spaced along its rise, which add to its height without exceeding zoning allowances. (By similar sleight of hand, 432 Park is only shorter than One World Trade because the latter’s spire was ruled, perhaps patriotically, a spire — not an antenna.) Beal observes that such a building is only at all practical for apartments, since its narrow elevator core could never support office traffic.

Yet it doesn’t work so well as housing. “This is not a building for New Yorkers,” he writes — “few people who have spent any significant amount of time in New York, given unlimited resources, would choose to live in Midtown.” The water pressure is iffy. The top floors sway an unsettling amount. Perhaps as a result, perhaps also by design, 432 Park functions mostly as a warehouse for overseas wealth, as oligarchs park their money in cubical condos they may never visit, let alone call home.

The rise of this bloodless, gusty, inhuman city provides Sandfuture’s last image, and a metaphor for the next phase of United States empire. Beal’s vision turns from a view of 432 Park, seen from the middle of the Brooklyn Bridge, to the newer, taller, thinner towers rising around it — then catches on an empty trash barge passing under him, heading south, “where it disappeared from view.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Travis Diehl is a freelance critic and writer and online editor at X-TRA. His work appears in The Baffler, Art in America, frieze, Artforum, art-agenda / e-flux journal, East of Borneo, and the Los Angeles Review of Books, among others. He is a recipient of the Creative Capital’s Arts Writers Grant and the Rabkin Prize in Visual Arts Journalism.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Summer Words

Travis Diehl finds himself "Lost in Summerland," the new essay collection by Barrett Swanson.

Our Commerce and Our Freedom, or Why I’m Leaving (for) New York

Events in a city as grand and grotesque as New York owe less to individual actors than to intractable tides.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!