Messing with Maps: Walking David Foster Wallace’s Boston

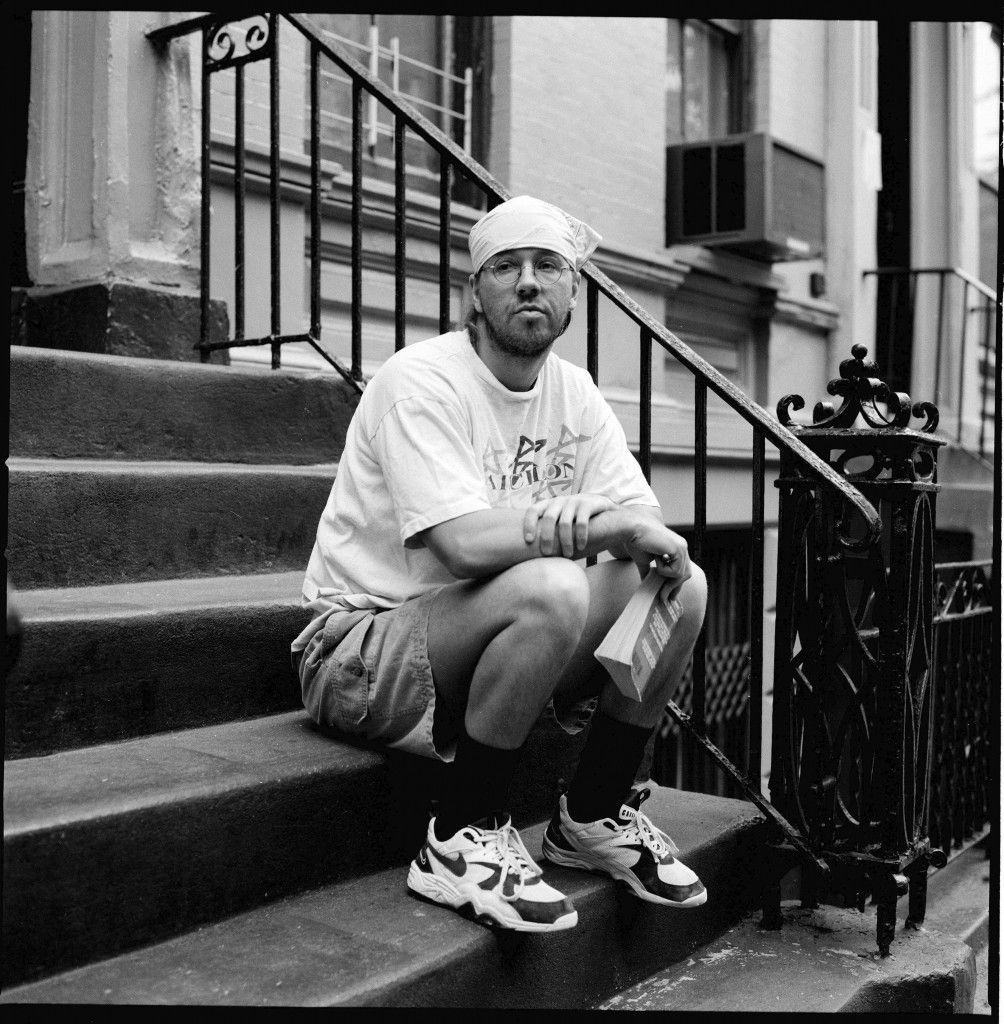

Bill Lattanzi explores "Infinite Jest" through the geography of David Foster Wallace's Boston.

By Bill LattanziFebruary 6, 2015

NEVER MIND Barthelme, Barth, Coover, Pynchon, and Nabokov. Underneath all the postmodern maneuvers in David Foster Wallace’s epic and enduring Infinite Jest, there’s a story written by another, more traditional American writer: the small-town kid who comes to the big city, gets overwhelmed by his experience, and through years of effort gains control over that experience by turning it into art. Or at least that’s the strong sense you get after you walk the streets of Boston and Cambridge with the novel, D. T. Max’s bio, and Bill Beutler’s amazing InfiniteAtlas.com as your guides. I started searching out the sites of Infinite Jest shortly after Wallace died by suicide in 2008. Like a lot of Wallace fans, I didn’t quite know how to work through my feelings, and exploring the geography of the novel seemed like something I could do. Since then, I’ve given a few tours to interested parties, including friends and fans and radio people and students of mine, as well as Adam Kelly’s class from Harvard, all of us to different degrees captivated by Wallace and wanting to get closer, to better understand him, to walk where he walked in some sort of strange, secular haj.

It’s weird. Wallace only lived here for three years, but you might think he was an Allston-Brighton lifer from all the geographic shout-outs in Infinite Jest. Hospitals, businesses, streets, schools, parks, tourist attractions, T stops, and signage all but crowd out the characters that move among them, each spot located with GPS-like precision. Maybe he was aping James Joyce, who hoped Ulysses could be used to reconstruct Dublin were it ever destroyed. But walking a couple of miles in Wallace’s footsteps makes Infinite Jest start to look more like a fragmented, compressed, and rebuilt version of every experience, thought, and feeling he had here, every one of them registered deeply in the writer’s part of his skull, transformed, slotted into a newly created imaginary space, and put to use.

Let’s start in Harvard Yard, at Emerson Hall, with its Boston brick, classical columns, and a line from Psalms chiseled across the frieze: “What Is Man That Thou Art Mindful of Him.” The place was supposed to be the heart of Wallace’s life when he moved here in April of 1989. Already a published, buzzed-about novelist at 27, he’d decided to chuck the instability of fiction writing to get his philosophy PhD. It was his version of giving up the dream and getting real. It didn’t work.

Six months after his arrival, he landed in McLean, Harvard’s tony psych hospital five miles west in Belmont. Wallace’s case was severe, the worst yet of several breakdowns he’d suffered, each one seeming to bring him closer to some final disaster. According to D. T. Max, the good folks at McLean sobered him up, crucially prescribed an antidepressant called Nardil, and packed him off across the river to a rehab unit. There, at Granada House, three miles straight south from Emerson Hall, Wallace would begin an education entirely different from the one he’d come for. From his fellow addicts, he’d learn about a whole other Boston, one in parallel with but invisible to the express lane of American success that he’d been traveling. Amazed, it seems, by his first contact with life at the bottom — its vitality, its brutality, and most of all its sadness, not that different from the sadness he knew — he’d pour his new knowledge of the democracy of pain into Infinite Jest, marking it out on the streets as if its invisible stories were burned on the sidewalks, every dumpster a monument.

“Its’ a fucking bitch of a life don't let any body get over on you different. And back we go to the Harvard Square.”

“Its’ a fucking bitch of a life don't let any body get over on you different. And back we go to the Harvard Square.”

Walk out the west gate of the Yard, and take a look as you pass the Carpenter Center. It’s Le Corbusier’s only US building, home to the Harvard Film Archives, champion of the avant and the obscure, where maybe Wallace took in some of the experimental films often on the bill by the likes of Hollis Frampton and Stan Brakhage, filmmakers lovingly parodied in Infinite Jest.

“The big brick cake of the hospital behind Krause in purple twilight.”

“The big brick cake of the hospital behind Krause in purple twilight.”

We’re walking east where thousands of college kids and no doubt Wallace himself walked on their way home to one of Cambridge’s student enclaves, Inman Square. At least it was a student enclave from the late ’70s when I lived there through the end of the ’80s when Wallace did. Biotech, urban renewal, and steam cleaning have changed the look of much of what was then a pretty spotty city, so to really see the elephant of Wallace’s Boston, you kind of have to put on a pair of grime-colored glasses. With those in place, a lot of buildings are still there and things come into the proper cruddy focus. Pass by the “big brick cake” of Cambridge City Hospital, where Poor Tony Krause knew he could get patched up and released since “it’s unfortunately not a free hospital, but it is a free country,” and his lack of insurance would allow him to push on just a few blocks to Antitoi’s, where the brothers Quebecois could be counted on for drugs.

“‘What is this place?’ ‘This, it is Ryle’s Inman Square Club of Jazz. My wife is dying at home in my native province.’”

“‘What is this place?’ ‘This, it is Ryle’s Inman Square Club of Jazz. My wife is dying at home in my native province.’”

When you hit Inman Square proper, you’re staring straight at Ryles Jazz Club, then the only upscale spot in the neighborhood, now a little less special, but still striking for its purplish-blue paint and big sign. Local hero Pat Metheny used to play there. You pretty much catch a glimpse of Ryles every time you come through the square, walking or waiting for the bus at the corner of Springfield Street. Wallace the philosophy kid must have chuckled every time he saw it, finding his philosophy texts writ in neon.

Gilbert Ryle, the dour-faced 20th-century English philosopher, seemed to have exactly zero jazz in him. Ryle’s view of the self as a machine and consciousness as a joke, an illusory “ghost in the machine,” plays a big role in Infinite Jest, but it’s a view that’s not unopposed, and not ever fully endorsed. In fact, if there’s one big metaphysical question that arcs over the novel, it’s whether Ryle is right. Are we a body only? Or is there something more? “I am […] surrounded by heads and bodies,” the thousand-page book opens, already laying out the terms of the debate: on the one hand, heads, full of thoughts, full of consciousness and some idea that a self might contain this thing called a soul and, on the other hand, bodies, distorted into every manner of grotesque, born and made, through the book.

It’s at Ryle’s that the wheelchair assassin Marathe promises the profoundly depressed Kate Gompert the most pleasurable experience of her life, if she’ll follow him “only three streets from here.” Gompert presumes this to be a pick-up line, but what Marathe is offering is a viewing of the fatal Entertainment — the infinitely addictive film titled “Infinite Jest,” now showing at Antitoi’s. And, indeed, Antitoi’s is three blocks away, all Wallace-obsessives agree, south on Prospect. But walk exactly three blocks in the opposite direction, north from Ryle’s, past the bus stop, up Springfield, and turn right, and you’re standing in front of 35 Houghton Street, home to Wallace and his best friend, novelist Mark Costello, that crazy spring, summer, and fall in Cambridge.

“There was no shortage of chaos around 35 Houghton Street,” Costello wrote. By many accounts, including Wallace’s own, he was bedding strangers continuously. “The phone rang at 3:00 A.M. and women banged on the back door two hours later.” I can’t help wonder if Marathe’s come-on to Gompert was also a knowing bit of self-skewering. Gompert’s reply is, “I’ve heard that one before, asshole.”

Back on the path to the Antitoi’s, we pass by the Tropical Dimension Food Store, one of the last of what used to be many inscrutable storefronts along Cambridge St. I lived in the neighborhood a few years before Wallace, and some of these storefronts were just compelling and bizarre mysteries to me, literal windows into other worlds. One of them, in my memory but not yet verified by research, fits almost exactly the novel’s description of the front of Antitoi’s: a small storefront displaying nothing but mirrors and Portuguese videotapes. I distinctly remember walking in one day just to see what the deal was, and two men, one sitting, one standing, looked up. I don’t know who was more startled, me or them. They had little English, I had zero Portuguese. I walked out, no wiser as to what the hell they were doing in there. So that’s always been Antitoi’s to me. The parking alley that leads to a parking lot out back, much like the novel’s “discreet back door … accessible by a parking alley” clinched it. Here are the Lady-or-the-Tiger set of six inscrutable doors that Poor Tony Krause, chased by a relentless Ruth van Cleve in pursuit of her snatched purse, aimed at in hope that “the dumpsters would keep It from seeing just which hopefully unlocked rear door” he disappeared into. The dumpsters and doors are there still.

But even if I’m right about the inspiration for Antitoi’s, Wallace has moved it from Cambridge Street three blocks south to Prospect. That spot is on the walk from Inman to the Red Line at Central Square, the fastest route into Boston from Houghton Street. The scholar David Hering puts Antitoi’s at the north corner of St. Mary’s, but I prefer the south. The single-story brick building there housed a nonprofit for thirty years with a nicely painted sign on the glass: Cultural Survival. Cultural Survival was a group started by Harvard anthropology professors who aimed to help tribal groups by linking them up to the West through trade. It’s tempting to think that when Wallace came to contemplate a book about our own culture as an endangered species, a storefront called Cultural Survival just might have “rung his cherries,” as he liked to say. Coincidentally, the Tsarnaev brothers, the Boston Marathon bombers, lived two blocks away.

For all the times I’ve walked the tour, I always start with the feeling that it’s a pretty trivial and meaningless thing to do. And it’s always at this midpoint in the trip, it seems, walking up Prospect toward Central Square, that the thing starts to come alive for me. I start to see the ghosts hovering a couple of inches above the ground: Lenz in his sombrero and fake moustache, morose Gompert, and Ruth van Cleve in her heels. The traffic, in the novel and in real life, is at a standstill. And I start to think about the “map and the territory” metaphor in the book, set up in the midst of the catastrophic schoolboy game of Eschaton, just as it’s about to descend into savagery: “‘It’s snowing on the goddamn map, not the territory, you dick!’ Pemulis yells at Penn.” Much critical ink has been spilled delving into the epistemological depths of that particular turn of phrase. But for me, it’s not about philosophy, it’s about something much closer to Wallace’s heart. It’s about the power of literature.

For all his suffering, all the chaos in his life around this time, Wallace seems to me to have taken the force of all of it into himself, and performed an incredible act of literary jiu-jitsu. The streets we’re walking, the building, the people Wallace met, and the experiences he had in real life, he has turned into a mere map. His lived world has become a map of a far more enduring territory, the territory that is the novel Infinite Jest. The buildings will crumble. Infinite Jest, read or not, is forever.

We’ve walked the few blocks to Central Square, spotted the IJ name-checked Cheapo Records on Mass. Ave. (now moved to the north side of the street), and headed underground. We’re leaving in-real-life Cambridge and heading out to imaginary Enfield.

We pass under MIT, where Wallace turned the student center into a massive brain.

We cross the river and catch our first glance of the CITGO sign, an advertisement so dear to Bostonians that there was a petition to have it declared a historic landmark. Athens has the Acropolis, Boston has an ad for gasoline. In Infinite Jest, it’s Gately’s “triangular star to steer by,” and an inspiration, maybe, for Wallace’s idea to structure the novel around a recursive fractal of triangles called a Sierpinski gasket.

The Red Line dives back underground to Park Street Station, Shaw’s Monument, and the gleaming dome of the State House above. Change for the Green Line and the screechiest turn in subway history at Boylston Street. Above lies Emerson College, where Mary Karr got Dave a job that led to the stability of his later years, teaching English to undergrads. We pass under the Public Gardens where fictional crowds in the Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment gather to watch what was in the ’90s the real-life annual draining of the Public Gardens.

“We go down to the library at Copley where we stash our personnel works when we crewed”

“We go down to the library at Copley where we stash our personnel works when we crewed”

The glories of McKim-White’s Boston Public Library are above us next, but from our seat on the T, we’re flying wraithlike around the back to check out the sewer grates where an addict named C. came to an ugly end. Iron bars now protect the grates from indignity in this most power-washed, photo-ready part of town.

The train rumbles out of the tunnel and aboveground after Kenmore, and the Citgo sign recedes behind us. Past BU and at the bottom of Heartbreak Hill, we land at Warren Street. We’re at the edge of fictional Enfield, which occupies the center of real-life Brighton.

It may not be possible to draw an accurate map of Enfield, but Wallace’s descriptions are so precise it seems he’s daring us to try. And of course, I have. And of course, I’ve failed. What was Wallace up to with maps? They’re so dead accurate … until they’re not.

“I have a hard time doing anything that’s real because there’s so much real stuff that I get overwhelmed,” Wallace told Chris Lydon on WBUR in 1996. “So I sort of like to mess with maps a little bit, and part of the book is about messing with maps.”

“That was actually the name of a town [that was called Enfield] close to where I went to college that was inundated for a reservoir.” — The Connection, 02/96

“That was actually the name of a town [that was called Enfield] close to where I went to college that was inundated for a reservoir.” — The Connection, 02/96

“A kind of arm-shape […] its fist sunk into Allston” is how Wallace describes Enfield in the book. That fist is problematic. If you follow the street references, there doesn’t seem to be room for it. I shrugged my shoulders at this — hey, Dave makes mistakes too — until this past September, when I met Ariane Mak, a young scholar studying at the Sorbonne. She pointed to an interview where Wallace says he was interested in “all this stuff about movement within limits and whether you can puncture the limits or not.” Her idea was that here was the puncture, set right onto the map. The fist rises up and punctures the map directly due north of Ennet House Drug and Alcohol Recovery House, where the addicts whose adventures we follow through the streets have come to get “less unhappy.”

In real life, of course, Wallace was one of those addicts, and the novel’s Ennet House matches nearly exactly the real-life location of Granada House in 1990, when Wallace was in residence.

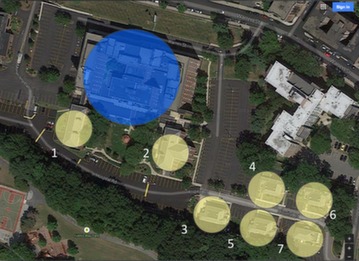

Just as in the book, Ennet/Granada is steps away from the T stop, but while you can look up and see it across the street, we have to walk up the hill and around because of the high iron fence at the edge of the grounds. We enter the Brighton Marine Health Center, the “seven moons orbiting a dead planet.” Google Maps gives you the satellite view.

At Brighton Marine, you can wander among the seven outbuildings for a good long while reading the passages and matching up the details. They are pretty darn close,

though reality, as may always be the case, seems smaller than the fiction.

At the end of a straight road to nowhere, with three buildings on either side, on the left, is the site of Granada House. Mansard roof, fire escape, bay windows where Pat Montessian had a view of “the unpleasant stretch of Commonwealth Ave.” — all of it checks out. Across Comm. Ave., there’s a bar. I don’t know if it was there in 1990, or if it was the inspiration for “The Unexamined Life,” where Pemulis and the cops drink, but I like to think so. The ravine is disappointingly small, more a little runoff of graded dirt from the construction than a Tim Burton castle on a hill. Looking out from Granada to #7 opposite, it’s easy to imagine the book’s image of a massive boulder rolling down Heartbreak Hill and crushing it from the construction of Enfield Academy above.

Wallace must have walked a lot, that’s my conclusion. He must have walked from Inman to Harvard and Central Squares as a student and now in Brighton, walked as a recovering addict. Granada was small and stuffed with people (“too full of residents,” says the book). Wallace smoked, chewed tobacco. He couldn’t drink. His thoughts never stopped. He must have had to get out of there. He must have walked. In Signifying Rappers, Costello said that back in Somerville they walked as a practice. “In 1989 humanity lacked the great and hungry search tools of today, Google, Yahoo, YouTube, Bing. But on mild Friday nights in dense-packed urban areas, we did possess another life-enlarging search engine. It was called walking.”

I think he walked the streets of Allston/Brighton relentlessly. I think the rambles of Lenz and Green were built on streets he’d walk, sometimes for purpose, like walking home, and sometimes for no purpose, to amble, to think, to not think, and, most importantly, to not get high or drunk.

I think he walked up the hill and around the back of Brighton High School to the top that had been flattened to make way not for an academically advanced tennis academy but for a monastery.

St. Gabriel’s was a Passionist monastery, devoted to the Passion of Christ. The grounds were purchased from the Nevins family, and a grand Spanish mansion called the Bellevue Estate came with it. From its founding in 1908 until 1978, St. Gabriel’s welcomed non-clerical members of the public in search of retreat. With Passionism on the decline, the monastery was closed and sold to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in 1980, but with a special provision. The monks in residence could stay, and religious function would continue until the death of the abbot. I don’t know if Wallace was aware of this, but it seems particularly apt. A group of monks whose half-life had passed, their Passion out of date, out of time, yet persisting in a world where entertainment and commerce were increasingly at the center. A little like Infinite Jest’s wraith, the place was neither alive nor dead. The monks were there in 1989. Did Wallace go in for a chat?

Out back, I was hoping I could see Granada House, but trees and buildings obscure most of the Brighton Marine complex. The bucolic lawn in the old photo is long gone, replaced with a crumbling blacktop driveway. It’s hard to look at the big exhaust fan on the top of the parking lot and not decide that it was the inspiration for the ATHSCME fans that blow the toxic fumes of pollution north and keep Boston clean.

When I take people on the Wallace Tour, I like to read the passage here about Mario, pure of mind and deformed of body, and his wandering from the tennis academy on the hill down to Ennet House, where even though it smelled like an ashtray, Mario felt at home. It’s the honest emotion and caring he admires: “The Headmistress is kind to the people and the people cry in front of each other.” And I like to end by walking all the way to the back of the lot to look north. There, behind the big exhaust fan, and Brighton High School, and the Charles River, you can just see the white spires of Harvard University, tiny in the distance. It’s a distance of a couple of miles and a whole world away from where Wallace had started just a year before.

¤

LARB Contributor

Bill Lattanzi is a writer and filmmaker who lives in Boston. He is working on a film about the work of David Foster Wallace.

LARB Staff Recommendations

What Would DFW Do: Maria Bustillos, Eric Been, and Mike Goetzman on “Both Flesh and Not” and All Things Foster Wallace

Infinite Proofs: The Effects of Mathematics on David Foster Wallace

To the extent he was home anywhere, DFW was at home in the world of math.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!