Melodrama and the Abyss: On María Amparo Escandón’s “L.A. Weather”

Yxta Maya Murray finds a call to action with the melodrama of “L.A. Weather” by María Amparo Escandón.

By Yxta Maya MurrayOctober 8, 2021

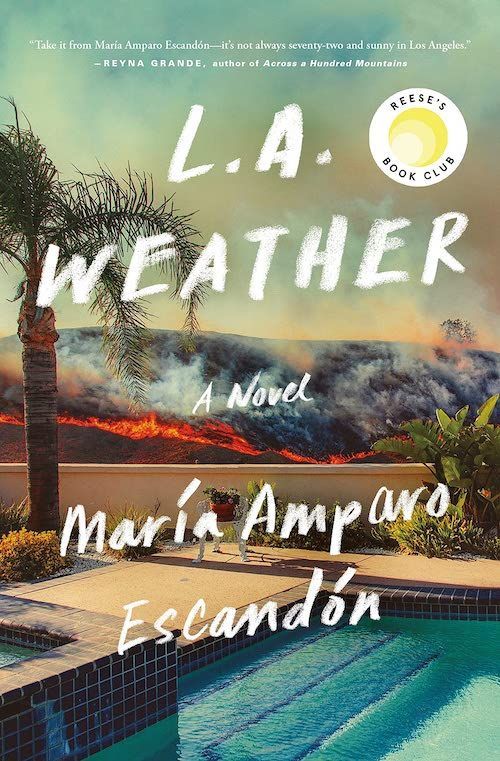

L.A. Weather by María Amparo Escandón. Flatiron Books. 336 pages.

IN THE MID- to late 2000s, Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht wrote about his work with indigenous people and colonists who farmed in the Upper Hunter Region of New South Wales, Australia. The farmers had once “lived close to the land and the weather […] receptive to big vistas, the brilliance of the Milky Way above their properties at night, abundant wildlife — from micro bats to kangaroos — prolific birdlife, and the pure, sweet scent of petrichor after much needed rain.” But when the landscape became devastated by drought, as well as the effects of large-scale coal mining in the region, the farmers exhibited an emotion that Albrecht described as being close to, but not completely mapped onto, nostalgia. What was this gloom that the farmers experienced? Albrecht coined a new term for that sensation, calling it solastalgia, based on “solace” and the Greek word “algos,” designating pain. Solastalgia, Albrecht emphasized, captured the farmers’ “negative affect” when exposed to environmental change, a misery that is “exacerbated by a sense of powerlessness or lack of control over the unfolding change process.” Albrecht’s solastalgia swiftly entered the lexicon to describe people’s sadness at the hot, ugly, and eventually fatal consequences of global warming and neoliberal ecological pillage.

Solastalgia is a word for our time — like right now, considering the repeated waves of destruction that climate change has unleashed in the United States and everywhere else. These traumas are so fresh, and so overwhelming, that we might now find ourselves past the lack-of-solace stage and should consider upgrading the term to eco-panic, enviro-catatonia, or bionomic hysteria. I noticed the first pangs of this stress in myself and in my friends in 2006, when Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth played in Los Angeles theaters during a heat wave that reached up to 119 degrees in Southern California, causing about 30,000 people to lose power and killing at least 147 people across the state. Since then, extreme weather, such as that which led to the 2008 floods in Southeastern Yemen, 2017’s Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, and this summer’s deadly flooding in Germany and Western Europe (just to name a few catastrophes), has been linked to climate change. Then there are the fires, whose names read like some ghastly roll call — in SoCal alone we can count the Woolsey, Thomas, Creek, Skirball, and Bobcat fires within the past few years, and that’s just getting started. Whatever emotional resources we might have relied upon to keep calm were further sapped this August, when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued its Sixth Assessment Report. This memo cautions that “[g]lobal warming of 1.5°C and 2°C will be exceeded during the 21st century unless deep reductions in CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions occur in the coming decades.”

With our new reality, and with the emotions it triggers, has come a change in literature. “Cli-fi,” or climate fiction, has been with us since the story of Noah and the Flood, not to mention Jules Verne’s The Purchase of the North Pole (1889), J. G. Ballard’s 1960s novels The Drowned World (1962) and The Drought (1965), Guido Morselli’s 1977 Dissipatio H.G., and Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower (1993). But the last decade has seen an explosion of these kinds of books, including Nnedi Okorafor’s Who Fears Death (2010), Maja Lunde’s The History of Bees (2015), John Lanchester’s The Wall (2019), Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island (2019), and a plethora of works published this year, including Jeff VanderMeer’s Hummingbird Salamander and Alexandra Kleeman’s Something New Under the Sun. These works engage the traditions of Africanfuturism, anti-colonialism, myths and legends, dystopian literature, and speculative fiction to examine the horror of a world where death by natural disaster is commonplace. They also remind readers of the 21st century’s complex truth: it might be too late already, but we still need to change our ways.

María Amparo Escandón enters the fray with her new novel, L.A. Weather, which tells the story of the wealthy, Los Angeles–based Alvarados, circa 2016. Oscar and Keila are the heads of the family, and their three daughters are Claudia, a chef; Olivia, an architect; and Patricia, who has a job in social media that I don’t quite understand. L.A. Weather is a Latinx family melodrama set in Los Angeles, revolving around Oscar’s depression over changes in the climate, which threaten the survival of an almond ranch that he has secretly purchased. Keila, a clay artist, cannot understand why her normally robust and energetic spouse has suddenly taken to staring out of the window and taking long drives, only to return home in a car covered with dust (residue from his visits to his orchard). Keila is a take-charge kind of person: charismatic, beautiful, vibrant, a loving mother, and an active exhibitor of her works — she often travels to Mexico City to hold shows at her gallery there. Oscar’s new malaise does not fit in with her active lifestyle, and her disappointment and impatience with him swiftly degrade into threats of divorce.

This crisis coincides with the calamities of their three daughters, who are each unhappily married. Olivia’s husband, a realtor named Felix, is verbally abusive and torments her with the threat of destroying two embryos they’ve been keeping in a deep freeze. Claudia is a kleptomaniac architect married to literary scout Gabriel, who is away all the time in New York supposedly working, but also spending a fair amount of time cheating on her. Patricia is married to a French trends strategist named Eric, but she does not live with him, instead cohabitating with her parents and her gender-fluid child, Dani. The family is warm and witty and spends a lot of money, even as ecological peril looms ever closer: in L.A. Weather, Escandón treats her readers to the Alvarados’ fabulous life, which is full of gourmet food, fashion, travel, and the trappings of bourgeois success. One particular scene finds Patricia trawling the still-open Barneys New York while trying to fend off her anxiety about her parents’ relationship and her own: “She wandered off to the shoe department to distract herself. She tried on a pair of Louboutin ankle boots that she had added to her shoe board on Pinterest. John Varvatos had some nice ones, too. She finally picked a pair of studded, laceless Sartore boots, perfect for her boyfriend jeans.”

As Keila and Oscar’s relationship disintegrates, however, the Alvarado family’s fortunes do too: Claudia experiences a terrible health crisis, which further sets in motion events that unwind each of the daughters’ marriages. The younger women cling to each other and to their parents during this difficult time, and Escandón continually emphasizes how family is everything to the Alvarados — a source of strength, power, consolation, and, yes, solace during this period where their hearts are breaking and the earth itself is in flames. In Escandón’s tale, Los Angeles’s wildfires, strange orange skies, and ashen air are a constant backdrop, and these corrosions express the ordeals endured by the clan. “L.A. weather” illustrates particularly Oscar’s own suffering, as he enters into an ever deeper state of midlife depression and confusion. “May Gray is not only a local climate phenomenon in Los Angeles; it’s a state of mind,” he thinks halfway through the novel, “it could take the form of a depressing marine layer over beach cities, [or] annoying smoke from brushfires pushed by wind against the San Gabriel or San Bernardino Mountains.” His anguish is only exacerbated by the possible loss of his almond orchard and his wife’s refusal to support him through his mental health battles, largely because he has left her in the dark.

Escandón, whose earlier novel Esperanza’s Box of Saints (1999) topped the Los Angeles Times’s best-seller list, excels at keeping the pace brisk and the characters’ personal trials intriguing, though the resolution of the family’s core problems do not, in the end, quite convince. Patricia and Eric’s relationship never struck me as fully realized, so their breakup does not spark any readerly feeling; Felix is confoundingly abusive and seems less like a well-rounded character than someone we are designed to hate; one of the women has an affair, and her husband reacts in such a gentle and self-effacing way that it does not seem real. Still, the climate anxieties addressed in the novel are gamely handled by the family’s decision to dedicate themselves to eco-consciousness, and their resolutions to recycle and scale back their consumption resemble the fumbling, half-hopeful, agitated promises that I, at least, periodically make to the planet.

The most interesting part of L.A. Weather is Escandón’s use of melodrama to engage our slide into the abyss, which makes it a different kind of offering than the dystopian and sci-fi works listed above. As film scholar Dan Flory writes in an essay about the pioneering Black silent filmmaker Oscar Micheaux (writer and director of Within Our Gates [1920] and The Exile [1931]), “melodrama’s close connection to specific ways of life, its emotive power, and its focus on the moral virtues of its characters suit it especially well to [our] investigations of contradictions.” In Micheaux’s case, this histrionic style helped him limn the paradoxes of a US society that ostensibly considers all human beings equal and yet oppresses and stigmatizes Black people. In other words, melodrama’s traffic with heightened emotions, conflicts, and morality makes it a helpful literary mode when exploring social problems such as racism or, as here, environmental collapse.

Given L.A. Weather’s focus on the nearly obsessive consumerism of one wealthy Latinx family, some of the most devastating aspects of climate change are not addressed with specificity. The novel does not much look at the unequal racial effects of global warming, which causes low-income people of color to struggle with acute respiratory problems and is feared to deepen racial and class inequalities surrounding housing and food. L.A. Weather, instead, creates a kind of climate melodrama-morality tale within the atmosphere of a Latinx Melrose Place or Falcon Crest. This is not necessarily the worst strategy for a literature that seeks to awaken its readers to our current troubles. Secreted within the dramas and the glamour of the novel is the intimation that the world around us is falling apart. Perhaps some readers feel better processing that information when it is conveyed on the wings of Escandón’s family opera rather than in the dry prose of the IPCC report, or even a book that deals straight on, and harshly, with the intersecting problems of environmental ruin and racial and class injustice. Personally, as I get older, I like my literature as truthful and bleak as it gets. The devastations of Morselli and Okorafor make me feel something intensely, and that’s the kind of energy that helps me take action. But, as I’ve already noted, climate change is already triggering our extreme reactions, from the melancholy of solastalgia to out-and-out terror. It may be that we are becoming so dumbfounded that direct ecological messaging will not be able to penetrate our paralysis. So why not wrap up the call to action inside some popular-lit pleasure? It might widen the audience for this kind of warning. That is Escandón’s achievement here, and I applaud it.

¤

Yxta Maya Murray is a writer and law professor who teaches at Loyola Law School.

LARB Contributor

Yxta Maya Murray is a writer and law professor who teaches at Loyola Law School.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Thirst That Big: On Alexandra Kleeman’s “Something New Under the Sun”

Kleeman’s new novel is a eulogy, a ghost story, and an ode to the ways and forms of life destroyed by human appetites.

What Does It Take to Create a World?: On Lynell George’s “A Handful of Earth, A Handful of Sky: The World of Octavia E. Butler”

Gerry Canavan visits the world of Octavia E. Butler in Lynell George’s “A Handful of Earth, A Handful of Sky.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!